Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

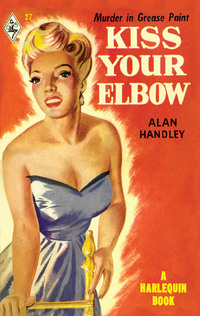

Loe raamatut: «Kiss Your Elbow»

Dear Reader,

Harlequin is celebrating its sixtieth anniversary in 2009 with an entire year’s worth of special programs showcasing the talent and variety that have made us the world’s leading romance publisher.

With this collection of vintage novels, we are thrilled to be able to journey with you to the roots of our success: six books that hark back to the very earliest days of our history, when the fare was decidedly adventurous, often mysterious and full of passion—1950s-style!

It is such fun to be able to present these works with their original text and cover art, which we hope both current readers and collectors of popular fiction will find entertaining.

Thank you for helping us to achieve and celebrate this milestone!

Warmly,

Donna Hayes,

Publisher and CEO

The Harlequin Story

To millions of readers around the world, Harlequin and romance fiction are synonymous. With a publishing record of 120 titles a month in 29 languages in 107 international markets on 6 continents, there is no question of Harlequin’s success.

But like all good stories, Harlequin’s has had some twists and turns.

In 1949, Harlequin was founded in Winnipeg, Canada. In the beginning, the company published a wide range of books—including the likes of Agatha Christie, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, James Hadley Chase and Somerset Maugham—all for the low price of twenty-five cents.

By the mid 1950s, Richard Bonnycastle was in complete control of the company, and at the urging of his wife—and chief editor—began publishing the romances of British firm Mills & Boon. The books sold so well that Harlequin eventually bought Mills & Boon outright in 1971.

In 1970, Harlequin expanded its distribution into the U.S. and contracted its first American author so that it could offer the first truly American romances. By 1980, that concept became a full-fledged series called Harlequin Superromance, the first romance line to originate outside the U.K.

The 1980s saw continued growth into global markets as well as the purchase of American publisher, Silhouette Books. By 1992, Harlequin dominated the genre, and ten years later was publishing more than half of all romances released in North America.

Now in our sixtieth anniversary year, Harlequin remains true to its history of being the romance publisher, while constantly creating innovative ways to deliver variety in what women want to read. And as we forge ahead into other types of fiction and nonfiction, we are always mindful of the hallmark of our success over the past six decades—guaranteed entertainment!

Kiss Your Elbow

Alan Handley

MILLS & BOON

Before you start reading, why not sign up?

Thank you for downloading this Mills & Boon book. If you want to hear about exclusive discounts, special offers and competitions, sign up to our email newsletter today!

Or simply visit

Mills & Boon emails are completely free to receive and you can unsubscribe at any time via the link in any email we send you.

ALAN HANDLEY

Emmy® Award-winning director Alan Handley had a celebrated career on stage and in television that spanned thirty years. He started off as a stage actor in the 1930s before moving into directing and producing shows such as The Dinah Shore Show. He won an Emmy® for directing a Julie Andrews special in 1965. He passed away in January 1990 at the age of 77.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER ONE

I WAS IN BED—WHICH IS WHERE I usually am at ten o’clock in the morning—when the phone rang.

“What’s with you? This is Nellie.” As though it was necessary to tell me who it was with that croak for a voice, even if she did wake me up. I lit a cigarette because she liked to talk for a long time and so do I and she was paying for the call and I didn’t have anything else to do.

“I’m still in bed.”

“Well, do you think you could get that long lean brownness the hell out of that bed for a job?”

“How much? It’s a nice bed.”

“Twenty-five a day for maybe three days or more. Of course, if you’re not interested, I got a book full of youth and beauty right here at my elbow.”

“If it’s more of those smoker pictures, the answer is no.”

“Now, Timmy, darling, you know that wasn’t my fault. They told me that short was only for advertising purposes. Besides, the money was good.”

“Well, I don’t need that kind of advertising yet. What’s the gag this time?”

“Can you be in my office in an hour?”

“Tell me now.”

“I tell you nothing till you sign Nellie’s little receipt book. Do you or don’t you?”

“Make it an hour and a half?”

“Who’s there with you?”

“Nobody,” I said. “And besides, what’s it to you?”

“If there’s nobody there, you can make it in an hour. Eleven sharp. Those are my last words.” And she banged up the receiver.

Twenty-five bucks a day for three days…that must be a picture…maybe I can get a close-up…be nice to the cameraman and the assistant director…one good close-up…who knows what might happen? Once more into the breach, dear friends…

So I got up, showered and started to get dressed. Thank God I had a clean shirt and my suit had just been pressed, because for twenty-five bucks a day, no matter what tricks Nellie was cooking up for me, I had to be good. I got into my gray double-breasted, which is one of my two answers to a couple of my more unkind friends that I have got another suit besides a dinner jacket. I did look through the pockets of my evening clothes to see how much money I had. There was nine dollars and some change together with match folders from the Barberry Room, the Stork and the Ruban Bleu. Diana, the woman I’d been out with last night, and I had certainly been on the town. I had to get this job of Nellie’s or I was going to be very, very hungry in a couple of days.

I put the money in my pocket and the folders in the bureau drawer where I save the ones from the tonier places. It sometimes impresses people when you’re trying to get a job if you pull out one from the Stork or “21.” I finished dressing and put on my coat and hat and went out.

The rooming house where I live was nicknamed the Casbah by one of the inmates after seeing that Boyer movie a long time ago and the name stuck. It’s just off, but not quite far enough off, Sheridan Square and on Saturday nights when the visiting firemen make a tour of Greenwich Village—which usually means Jimmy Kelly’s or a couple of the joints on Fourth Street—we get the usual drunks being sick in the vestibule or ringing the bell and asking for Marge. The Casbah like most rooming houses usually has a couple of transient Marges in spite of the professional jealousy of Helga who runs it, but on a Saturday night the Marges can pick their own drunks.

In the hall I ran into Kendall Thayer, who promptly hit me for a couple of bucks and I, like a dope, let him have them.

Whenever I get really depressed, which isn’t often because I have a lot of little tricks worked out to keep it from happening, I think of Kendall Thayer. He’s a but-for-the-grace-of-God-there-I-go lad. He’s me in cornstarch. Years ago he was a very famous silent picture leading man with a swimming pool and the works, but the bottle moved in and the works moved out, and now he’s ended up just another lush in the smallest and cheapest room in the Casbah, and, believe me, that’s small and cheap.

Like the rest of us, he feels that a break is just around the corner, the break that will get him another movie contract and put him right back up there. After all, he says, C. Aubrey Smith and Edmund Gwenn can’t live forever, just as I say that Tyrone Power and Hank Fonda and Gregory Peck weren’t born on a movie set, and people lent them dimes to eat in their day, too.

Kendall manages to get odd jobs once in a while with radio audience-participation shows where they have plants in the studio. He usually gets five bucks a throw and six cakes of soap or a carton of breakfast food, which he tries to peddle to other people in the Casbah, but recently business has been off all over town.

“You going out, Tim?” he asked me.

“Yeah, got a call,” I said, dealing him out the two dollars. That left me seven.

“Going to be out long?”

“I don’t know. Hope it’s for a job. Why?”

“I was just wondering if you’d let me have the key to your door. I left your phone number and I’m expecting a call and it’s rather important. I’d prefer it didn’t come over the house phone.” I could understand that because the only phone besides mine in the Casbah is out in the hall and everybody knows what is said over it even before the person talking.

So I said, “Sure. Here’s the key, but don’t mess with my studs and cuff links.” He gave me what, I am sure, back in the silent days was famous as his rueful smile, and I went on downstairs and out on the street.

I stopped at the Riker’s on the corner of Sheridan Square for orange juice and coffee and went down the subway hole at exactly ten forty-five.

I took the uptown local to Fourteenth Street and closed my eyes and prayed. If there’s one thing that’s going to drive me nuts quicker than anything else, it’s living on a local subway stop.

I used to be able to treat it as a game. But now I’ve gotten superstitious about it. It’s become an omen, and can wreck my whole day.

If, when I get to Fourteenth Street, which is an express stop, and the express is waiting right there…it’s a red-letter day. Then all I have to do is run across the platform and there I am at Times Square in two stops. But when the local pulls in and there isn’t an express there, I start quietly blowing my top. It’s ridiculous, I know, but so is the superstition about whistling in dressing rooms or saying the last line of a play in rehearsal. I don’t suppose I make or lose two minutes either way, but this subway business when it doesn’t work out right is the black cat across my path, or the broken mirror. And today when I decide I’ll take a chance and change to an express, it gets lost over in Brooklyn or someplace and I know of two locals, at least, that beat me to Times Square. That was a sure sign that today was going to be a not day and I should have stayed in bed.

I got to Times Square nervous and mad and feeling like saying to hell with Nellie and going over to one of the flea-bag movies on Forty-second Street and giving my evil omens time to cool off. I would have, too, except that I had just seven bucks in the whole world, and twenty-five bucks is twenty-five bucks.

So I walked up Times Square past the Paramount Theater Building—which when I first came to New York was considered a cathedral of the motion picture or something, but is now just where high school kids play hookey with name bands. And then on the corner of Forty-fourth Street, which I had to pass to get to the Shubert Building and Nellie’s office, was Walgreen’s Drug Store.

When you’re in grammar school, there’s always a Sweet Shop or Pete’s where you go after school and hang around. In prep school or high school there’s the Jigger Shop or Joe’s or Ye Sweete Shoppe, and in college there’s the Den or Mike’s, so you might know that when you enroll in the theater there would be some hangouts, too. There are, and one of them is Walgreen’s Drug Store. And it’s the first rung on the ladder. When you get a little bit better jobs you start dropping in at Sardi’s, and then, maybe the first time you get billing, it’s “21” and Toots Shor’s or the Stork or Morocco, and when you’re tops it’s the Colony at the right table.

Anyhow, here’s Walgreen’s. I guess it’s a good idea having a place like that. Trying to get ahead in the theater is a lonely business and any opportunity to huddle in groups is gratefully received. But I didn’t have time to huddle this morning.

The little bar in Sardi’s restaurant was empty except for the bartender polishing glasses. After all, eleven o’clock is a little early even for actors to start in—except the ones that can’t get out of bed without brushing their teeth with a belt of gin, and they were still in bed…belting away.

Nellie’s alleged office is across the street from Sardi’s in the Shubert Building, and Nick Stein with a couple of polo-coated singers was already in the elevator when I got on. Nick’s an assistant press agent and runs a syndicated gossip column in a lot of out-of-town newspapers. I give him tips once in a while, and he mentions me once in a while and also gives me ducats for shows he’s handling, which are useful for paying back obligations and, sometimes, you can even sell them.

“What’s with you, Tim?” Nick asked me. “Get any items? Did you make the rounds last night?”

“Yeah,” I said. “When I think of the ulcers I save you…” I told him one I’d heard about the Broadway producer who’d been clipped for plenty by three previous wives, so now, every time he gave his current wife a present he actually insisted she sign a paper saying it was hers only so long as she was married to him. “How’s that?”

“Not bad. Stop by the office with me, and I’ll fix you up for a show tonight.” So I rode up to the tenth floor, and Nick gave me three seats to one of his frantic flops one jump ahead of the stop clause.

Coming back to the hall with the tickets, the indicator said both elevators were on the ground floor, so it was quicker to walk down to Nellie’s office. Somebody else was on the stairs a couple of flights below me. I couldn’t see who it was though I could hear shoes clanging on iron treads. Whoever it was seemed to be in an awful hurry.

Nellie’s roost consists of two connecting cubicles at the end of the dark corridor. Waiting actors are the only ones that ever use the tiny front room, except when Henry Frobisher is producing a play and then Nellie gets grand and installs a secretary who is usually some unemployed actor working for peanuts on the chance that Nellie will get him a job with Frobisher, which, of course, she never does.

The first room was empty when I opened the door and walked in, which wasn’t unusual because most people who make the rounds have learned that Nellie doesn’t show till after lunch unless she’s very busy and that’s practically never. By waving aside the stale cigarette smoke laced with gin that hung from the ceiling like portieres, I could make out Nellie leaning over her desk and I started to walk back to her.

I guess I must have said something silly, like “Boo! you pretty creature.” I usually do, but it didn’t make any difference whether I did or not because Nellie didn’t hear me. Nellie couldn’t hear me. Nellie was dead.

CHAPTER TWO

I JUST STOOD THERE STARING at her. She was flopped across her desk and had filed herself about as neatly as anything else in that rats’ nest on her old-fashioned country editor-type filing spindle. I could see the heavy wrought-iron base of the spindle jutting out around the edges of her right breast. There wasn’t much blood, which is probably the reason I didn’t start heaving, because in the army I developed sort of a thing about blood.

Nellie alive and kicking is nobody’s dream girl. She’s a chiseler, an agent, a sharpie with a shady buck. She’s fat and sloppy and although she undoubtedly owns another dress, I don’t remember ever seeing her in any but this mottled grayish-green job which bitchy actors are apt to swear stopped being a dress years ago and now just grows on her like moss. But all the same, I was kind of fond of her.

I felt for her pulse, which wasn’t—and that’s all. I’ve done enough of those where-were-you-on-the-night-of bills in summer stock to know better than to start juggling bodies around now.

Lying open and almost hidden under one pudgy arm and doing its bit toward helping her hair sop up the blood was Nellie’s Youth and Beauty Book, which was, besides the phone and spindle, all of Nellie’s office equipment. In it she kept all the names of actors and producers she knew, listed her appointments and stuffed it full of letters and bills. She must have had it refilled every year because it always had the same tooled leather cover.

Falling into the old first-act routine, I slid the book out from under her arm and looked at the page for today. As I figured, my name was down for an eleven o’clock appointment. There were three other entries ahead of mine. One I knew very well: Maggie Lanson. She was to be there at eleven, too. Nellie was supposed to have been at Chez Ernest, the chi-chi dress place at ten. The other name I couldn’t recognize. There were just initials for the last name. It was Bobby LeB. and he had an appointment for ten-thirty. That was all for the morning, but in the afternoon she was to see Henry Frobisher at his office at three-thirty, and she had a dinner date with a little ingenue around town I knew, as who didn’t, named Libby Drew.

Suddenly the phone rang. That was the cue for me to start blowing up in my scene and almost closed me before I opened. I had moved the corpus—at least the arm—when I pulled out the book, and I didn’t want to get in any jam. My name was in that book and there was nobody around to knock some sense into me, and the damned phone kept ringing and ringing and I couldn’t bring myself to answer it. Suddenly I got a load of a scene behind a gauze scrim I didn’t want any part of—me sweating under a lot of blinding lights with all the Irish character actors in town waving rubber hoses at me and shouting, “Who done it, Runch?” and me not being able to tell them. When I play that scene I want to have a few of the toppers.

Then the montage began. You know, lots of presses running and front pages flying at you like bats out of hell and banner heads screaming “Actor Slays Agent” and “Fiend Convicted.” If only the phone had stopped that ringing or I had stopped that nonsense of thinking I was playing the lead in some crappy whodunit at the Rialto and done what I should have done, everything would have been all right. At least for me. But no…Once a ham always a ham. So I picked up the Youth and Beauty Book and stuck it under my coat—still like in reel two—and copped a sneak.

The hall was empty. I had another brain wave and walked back up to the tenth floor and got on the elevator there and rode down. The only stop was the fifth floor where two polo coats got back on.

I did a walk-not-run out onto Forty-fourth and aimed west. I didn’t want to pass Sardi’s or Walgreen’s again because by this time I had worked myself up to such a point that if somebody had said Boo! to me, I’d have waved aside the black mask and asked for that final cigarette.

CHAPTER THREE

I WALKED UP EIGHTH AVENUE for a couple of blocks trying to decide what to do. The Forty-second Street fleabags didn’t seem to solve anything, though in all the books, ticket stubs seem to be wonderful alibis—except that the people that use them for alibis always seem to end up in the last chapter behind the eight ball. Which is where it looked like I was going to end up without costing me forty cents, either. Of course, I shouldn’t have taken the Youth and Beauty Book.

And then I thought of Maggie Lanson. Even if her name hadn’t been in the book for an eleven o’clock appointment, sooner or later I would have thought of Maggie Lanson. She is the only other person I know of in the world that feels the same way I do about most things. We are, as she is wont to say after a couple of slugs of pernod, sympatique.

She’s exactly my age, thirty-two, and was terribly pretty about ten years ago but the pernod hasn’t helped that part of it much. She’s quite rich, mostly from an early husband she divorced about seven years ago, and she tries to be an actress when she thinks of it. That was how I first met her. We were in the same show, my one hit, for six months right after her divorce. I guess she felt she had to have something to do nights.

I don’t know if I thought she would be able to tell me who had done Nellie in. Maybe she was early for her appointment or maybe she didn’t keep it at all—which wouldn’t be unusual. And if she did maybe she knew this Bobby LeB. She knew the most alarming collection of people. Anyway, Maggie was the only person in the world I wanted to see.

Her apartment, at the corner of Fifth Avenue and one of the Sixties, is on the fifth floor, and there is a buzzer system and a work-it-yourself elevator. I had a key because she didn’t mind my dropping in if I was in the neighborhood—whether she was there or not—provided I called up first and emptied the ash trays when I left. I dialed her number in the corner drugstore (only in that section of town they are called “chemists” or “apothecaries”) before walking over, but there wasn’t any answer so I went up to her apartment and let myself in.

It’s a nice apartment if you don’t mind stripes. Mostly gray and yellow stripes and lots of flowers. But the chairs are comfortable and the Capehart works and there’s generally plenty to drink. A big living room with a practical fireplace, a foyer, bedroom and bath and a minute kitchenette in which ice cubes are the only thing she knows the recipe for. I poured myself a mahogany Scotch because by this time it was two minutes after twelve, which made it legal as far as I’m concerned. Then I sat down and started thinking about how soon what had happened was going to hit me and what a jerk I was not to leave that damn book in Nellie’s office and call the cops. I took out the Youth and Beauty Book. The blood had dried on its edges, and on the page that had been open were a few squiggles in an unpleasant shade of brown that had been painted with Nellie’s own blood—her hair having been the paintbrush—when I pulled it out from under her.

It was a sort of hammering with a couple of low moans thrown in, all kind of muffled. It would go on for a minute, then stop for a few, then start again. At first I thought it was only that I should have watered my drink, but when it came the third time I knew it wasn’t the Scotch and it wasn’t me—it was in Maggie’s bathroom. So I got brave by finishing off the Scotch and, making with a bookend, walked over to the bathroom door.

As I was in this far, I might as well shoot the works. I grabbed the bookend even tighter and started to open the bathroom door, only there wasn’t any doorknob. It was lying on the floor right by the door. I picked it up and fit the square rod in the hole as quietly as I could, which wasn’t very, since I was holding the bookend at the same time. Softly I turned it and threw open the door.

There was Maggie, nothing on but a nightgown, lying on the bathroom floor with her chin in one hand and languidly pounding on the pipes under the wash basin with a big empty mouthwash bottle in the other. She looked up from her pounding and after reeling in her eyes, she recognized me.

“Angel,” she said, “for God’s sake bring me a drink.” She tossed the bottle in a corner where it shattered around a couple of times then lay still. I walked over to help her. My shoes crunched broken glass on the tile floor. “What happened to you?” I helped her to sit up. She yelped and, rolling over on one hip, looked at her behind. Blood was staining her sheer nightgown.

“Now isn’t that maddening? A brand-new one, too. Well, don’t just stand there, darling. Get me out of here.” I picked her up, carried her into the bedroom and deposited her gently, stomach down, on the bed. The cut wasn’t very deep, but was bleeding quite a lot. I gave her a face towel to hold on it while I ransacked the medicine cabinet.

“It was that damned doorknob coming off. I’ve been trapped in there for hours. I broke a couple of bottles pounding on the pipes, but no one would come. If you’re expecting to find bandages in that thing you’re wasting your time…. There’s nothing but sleeping pills.” She was right. “Call the superintendent. He’s very sweet. I don’t think it’s worth quite all this fuss, though I’m glad you came in when you did. I was running out of bottles. What about that drink?” I came back to the bed.

“Maggie, how drunk are you?”

“I’m not drunk, Timmy. Honestly I’m not. Well, maybe a little hungover, but I was in there for over two hours, and I do think I should be allowed to be just a little testy, if I want.”

“Can you grapple with a horrid fact?”

“Couldn’t it wait till I got bandaged up and had a real drink? It’ll keep that long, won’t it?”

“Yes. I think it’ll keep that long.” I phoned the superintendent on the little house phone, and he promptly brought bandages, Mercurochrome and a screwdriver.

He was most apologetic and fixed the doorknob in a few minutes. He could have done it even quicker if he had kept his eyes on his work instead of Maggie, who was still on the bed covered with a blanket trying to negotiate, while lying on her stomach, the drink I had mixed for her. I finally got him out and left Maggie to fix the bandage by herself and started pacing back and forth in the living room.

The cut wasn’t at all serious, but I was still a little queasy from it. Bleeding women, two in the same hour, were rapidly getting me down.

Maggie finally came out of the bedroom dressed in a blue housecoat with more stripes and brushing her hair.

“I know I’m stuck with that adhesive tape for the rest of my life. I used practically the whole roll.”

“At least you’ve got a cast-iron alibi.”

“Whatever should I want an alibi for?”

“Did you have any appointments this morning?”

The brush stopped in midair. “Oh my God, Nellie! I forgot all about it. She called yesterday and told me to come in this morning for a job. I’d better phone her.”

“You needn’t bother. She’s been murdered.”

“What a pity. Oh, well, I don’t suppose I’d have gotten the job anyway.”

“Maggie, I said that Nellie’s been murdered.”

“I heard you, dear. And about time, too, if you ask me.”

“What makes you say that?”

“But, angel…she’s an agent.”

“Maybe so, but sooner or later the police are going to want to know who killed her.”

“What are you getting in such a tizzy about? It isn’t anybody we know, is it?”

“Maybe it is.”

“Oh, good. Who? Tell me.”

“I thought perhaps you’d know something about it. That’s why I came here this morning.”

“Believe me, Timmy, I’ve got something better to do than go around murdering Nellie Brant. I think I will now have another drink. No, you stay here, I’ll get them this time. Since I can’t sit down, I might as well be busy.” She went into the foyer to the bar and brought us back a couple of straight Scotches. “Would you like to play Gin Rummy? We could do it on the mantelpiece.”

“No, I would not like to play Gin Rummy. Please, Maggie, I’m serious.”

“I’m sorry, Timmy. I do mean to listen but that affair with the bathroom has made me rather jumpy. I wish I could sit down.” She pulled some pillows from the couch and lined them up on the floor and lay on her stomach. “There, that’s much better. Now tell me everything in one word.”

“Well, Nellie called me up this morning and…”

“What time was that?”

“About ten o’clock, I think.”

“And she was dead when you saw her, whenever it was? As a matter of fact, I don’t imagine she was dead at all. Probably drunk. She’s a notorious nipper.”

“She was dead, all right. I took her pulse. She was still warm, but definitely dead.”

“Oh, but that doesn’t mean a thing. I’m forever reading about people with no pulse at all carrying on like mad. I read about a chicken with his head chopped completely off, mind you, living to a ripe old age.”

I didn’t like it one bit that my big moment did not turn out to be a big moment after all. And besides, I knew Nellie was dead. The picture of that body kept coming into focus in spite of the Scotch. I kept fighting it, trying to make it vague and blurry again, but it didn’t work. I lay down on the floor beside Maggie and stared up at the ceiling.

“Here, lift up your head a minute.” I lifted up my head and she pushed a pillow under it. “Now lie back.” She stroked my forehead. Her hand was cool. It felt good. “Now then, tell me all. She called you at ten and then what happened?”

I told her exactly what had happened, or at least as near as I could remember. She thought it over for a moment.

“What about fingerprints? They’re very smart this season.”

“I had my gloves on,” I said. I was rather pleased with myself not to be caught with that one.

“Pretty damned clever, aren’t you, to…”

“Actually, I didn’t really plan it that way,” I said. “It just happened.”

“…to be able to take a pulse with your gloves on.” She finished on what I thought was an unnecessarily triumphant note.

And, of course, I must have taken my gloves off to feel for Nellie’s pulse. I admitted that rather sheepishly.

“And did you put your gloves back on right after you picked up the Youth and Beauty Book?” I couldn’t remember. “And did you close the door after you left?” Yes, I was positive of that. “Well, then, you have probably left a print large as life and twice as natural on the office door.” I tried desperately to remember if I had put my gloves back on or not.

Tasuta katkend on lõppenud.