Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «Wonders of the Universe»

For Mum, Dad and Sandra – none of this would have been possible without you

Brian Cox

For my dad, Geof Cohen (1943–2007)

Andrew Cohen

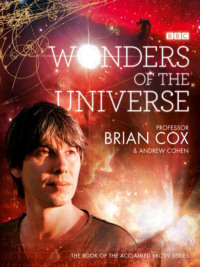

Wonders of the Universe

Professor Brian Cox & Andrew Cohen

Copyright

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The BBC logo is a trademark of the British Broadcasting Corporation and is under licence.

BBC logo © BBC 1996

The authors assert their moral right to be identified as the authors of this work.

WONDERS OF THE UNIVERSE. Text © Brian Cox and Andrew Cohen 2011. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Ebook Edition © MARCH 2011 ISBN: 9780007413379

Version 2017-02-03

Contents

Copyright

Introduction

The Universe

Chapter 1

Messengers

The Story of Light

Our place in the Universe

Our galactic neighbourhood

Mapping the Milky Way Galaxy

The shape of our galaxy

A star is born

What is Light?

Young’s double-slit experiment

Messengers from across the ocean of space

Chasing the speed of light

The search for a cosmic clock

Speed limits

Time Travel

To the dawn of time

Finding Andromeda

The Hubble Telescope

Hubble’s most important image

All the colours of the rainbow

Hubble expansion

Redshift

The Birth of the Universe

Visible light

Picturing the past

First sight

Chapter 2

Stardust

The Origins of Being

The cycle of life

Mapping the night sky

Stellar nurseries

How to find exoplanets

The orgins of life

The Periodic Table

The universal chemistry set

What are stars made of?

The Early Universe

El Tatio Geysers, Chile

The Big Bang

Sub-atomic particles

Timeline of the Universe: The Big Bang to the present

Matter by numbers

The most powerful explosion on Earth

From Big Bang to Sunshine: The First Stars

Red giant

Star death

Planetary nebulae

The rarest of all

Supernova: life cycle of a star

The beginning and the end

The orgin of life

Chapter 3

Falling

Full Force

The invisible string

The apple that never fell

The grand sculpture

The geoid

The Tug of the Moon

The false dawn

The Blue Marble

Galactic cannibals

Collision course

When galaxies collide

Feeling the Force

The gravity paradox

The land of little green men

What is gravity?

Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity

Into the darkness

The anatomy of a black hole

Chapter 4

Destiny

The Passage of Time

The cosmic clock

The galactic clock

Ancient life

The arrow of time

The order of disorder

Entropy in action

The life cycle of the Universe

The life of the Universe

The Destiny of Stars

The demise of our universe

The death of the Sun

The last stars

The beginning of the end

A very precious time

Searchable Terms

Picture credits

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Credits

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

THE UNIVERSE

At 13.7 billion years old, 45 billion light years across and filled with 100 billion galaxies – each containing hundreds of billions of stars – the Universe as revealed by modern science is humbling in scale and dazzling in beauty. But, paradoxically, as our knowledge of the Universe has expanded, so the division between us and the cosmos has melted away. The Universe may turn out to be infinite in extent and full of alien worlds beyond imagination, but current scientific thinking suggests that we need it all in order to exist. Without the stars, there would be no ingredients to build us; without the Universe’s great age, there would be no time for the stars to perform their alchemy. The Universe cannot be old without being vast; there may be no waste or redundancy in this potentially infinite arena if there are to be observers present to gaze upon its wonders.

The story of the Universe is therefore our story; tracing our origins back beyond the dawn of man, beyond the origin of life on Earth, and even beyond the formation of Earth itself; back to events – perhaps inevitable, perhaps chance ones – that occurred less than a billionth of a second after the Universe began.

AN ANCIENT WONDER

On Christmas Eve 1968, Apollo 8 passed into the darkness behind the Moon, and Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and William Anders became the first humans in history to lose sight of Earth. When they emerged from the Lunar shadow, they saw a crescent Earth rising against the blackness of space and chose to broadcast a creation story to the people of their home planet. A quarter of a million miles from home, lunar module pilot William Anders began:

‘We are now approaching lunar sunrise and, for all the people back on Earth, the crew of Apollo 8 has a message that we would like to send to you.

In the beginning God created the heaven and the Earth.

And the Earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.

And God said, Let there be light: and there was light.

And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness.’

The emergence of light from darkness is central to the creation mythologies of many cultures. The Universe begins as a void; the Maori called it Te Kore, the Greeks Chaos. The Egyptians saw the time before creation as an infinite, fathomless ocean out of which the land and the gods emerged. In some cultures, God is eternal: He created the Universe out of nothing and will outlast it. In others, such as some Hindu traditions, a vast primordial ocean predates the heavens and Earth. Lord Vishnu floated, asleep, on the ocean, entwined in the coils of a giant cobra, and only when light appeared and the darkness was banished did he awake and command the creation of the world.

We still don’t know how the Universe began, but we do have very strong evidence that something interesting happened 13.75 billion years ago that can be interpreted as the beginning of our universe. We call it the Big Bang. (We must be careful with our choice of words here, because this is a book about science, and the key to good science is the separation of the known from the unknown.) This interesting thing that happened corresponds to the origin of everything we can now see in the skies. All the ingredients required to build the hundreds of billions of galaxies and thousands of trillions of suns were once contained in a volume far smaller than a single atom. Unimaginably dense and hot beyond comprehension, this tiny seed has been expanding and cooling for the last 13.75 billion years, which has been sufficient time for the laws of nature to assemble all the complexity and beauty we observe in the night skies. These natural processes have also given rise to Earth, life, and also consciousness, which in many ways is harder to comprehend than the mere emergence of the seemingly infinite stars.

The work of the space programmes across the world cannot be viewed as a luxury, but rather as a necessity. It is through the missions of space shuttles such as Atlantis

The cosmos is about the smallest hole that a man can hide his head in.

—G.K. Chesterton

Care is in order, because the very beginning – by which we mean the events that happened during the Planck epoch – the time period before a million million million million million million millionths of a second after the Big Bang, is currently beyond our understanding. This is because we lack a theory of space and time before this point, and consequently have very little to say about it. Such a theory, known as quantum gravity, is the holy grail of modern theoretical physics and is being energetically searched for by hundreds of scientists across the world. (Albert Einstein spent the last decades of his life searching in vain for it.) Conventional thinking holds that both time and space began at time zero, the beginning of the Planck era. The Big Bang can therefore be regarded as the beginning of time itself, and as such it was the beginning of the Universe.

There are alternatives, however. In one theory, what we see as the Big Bang and the beginning of the Universe was caused by the collision of two pieces of space and time, known as ‘branes’, that had been floating forever in an infinite, pre-existing space. What we have labelled the beginning was therefore nothing more significant than a cosmic collision of two sheets of space and time.

It may be that the question ‘Why is there a Universe?’ will remain forever beyond us; it may also be that we will have an answer within our lifetimes, but the quest has to date proved more valuable than the answer because the ancient search for origins lies at the very heart of science. Indeed, it lies at the heart of much of human cultural development. The desire to understand events beyond the terrestrial seems to be innate, because all the great civilisations of antiquity have shared it, developing stories of beginnings, origins and endings. It is only recently that we have discovered that this quest is also profoundly useful in a practical sense. When coupled with the scientific method, this quest has allowed us not only to better understand nature, but to manipulate and control it for the enrichment of our lives through technology. The well-spring of all that we take for granted, from medical science to intercontinental air travel, is our curiosity.

THE VALUE OF WONDER

The idea that a journey to the edge of the Universe is deeply relevant to our everyday lives lies at the heart of Wonders of the Universe. I cannot emphasize enough my strong conviction that exploration, both intellectual and physical, is the foundation of civilisation. So whilst building rockets to the Moon and telescopes to capture the light from the most distant stars may seem like an interesting luxury, such a view would be superficial, incorrect and downright daft – to borrow a phrase from my native Oldham. We are part of the Universe; its fate is our fate; we live in it and it lives in us. How can anything be more important, relevant and useful than understanding its workings?

When we began to think about the series, we wanted to make programmes that were more than a simple tour of the wonders of the Universe. Of course black holes, colliding galaxies and stars at the edge of time are fascinating, and we see them all, but to characterise the ancient science of astronomy as a spectator sport would be to miss the point. The wonders we see through our telescopes are laboratories where we can test our understanding of the natural world in conditions so extreme that we will never be able to recreate them here on Earth. With this in mind, we decided to base the programmes around scientific themes rather than the wonders themselves.

When you set sail for Ithaca, wish for the road to be long, full of adventures, full of knowledge.

—C. P. Cavafy

Endeavour that we can truly begin to understand the origins and the workings of the Universe and use this information to plan for our future on Earth.

‘Messengers’ is about light – our only connection with the distant Universe that may lie forever beyond our reach. But it is also about the information stored within light itself, and how that information got there; the fingerprints of the chemical elements are to be found in the most distant starlight, enabling us to know with certainty the composition of the most distant star.

‘Stardust’ asks an ancient question: what are the building blocks of the Universe? And also, how was the raw material of a human being assembled from the debris of the Big Bang? – a searingly hot, yet beautifully ordered fireball with no discernable structure.

‘Falling’ tells the story of the great sculptor of the Universe: gravity. For some reason that we do not understand, gravity is by far the weakest of the four fundamental forces in the Universe, but because it has an infinite range and acts between everything that exists, its influence is all-pervasive. Our most precise theory of gravity, Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity, dates from 1915, which makes it the oldest of the modern theories of the forces. The theory of the electromagnetic force, Quantum Electrodynamics, dates from the 1950s, while the theory of the Strong Nuclear Force from the 1960s and 70s. Our description of last of the four, the Weak Nuclear Force, resides in the Standard Model of particle physics. This theory, a product of the 1970s, unifies the description of the Weak Nuclear Force with Quantum Electrodynamics, although there is a missing piece of the theory known as the Higgs Boson that is currently being searched for at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN in Geneva. Until the Higgs Boson, or whatever does its job, is found, we cannot claim to have a working description of the Weak Nuclear Force and its relationship with electromagnetism.

However despite the long pedigree and beautiful accuracy and elegance of Einstein’s theory of gravity, it is known to be incomplete. Our description of the Universe breaks down in the heart of its most evocatively named wonders. Black holes are known to exist at the centre of galaxies such as the Milky Way, and are dotted throughout the cosmos; the carcasses of the most massive stars in the Universe. We see them by their influence on passing stars and by detecting the intense radiation emitted by gas and dust that has the misfortune to venture too close to their event horizons. We have even seen their formation in the most violent cosmic events – supernova explosions. These events mark the destruction of stars that once burned brightly for millennia, completed in a matter of minutes.

The final chapter, ‘Destiny’, delves into the distant past and the far future; following the inevitable ticking of the universal clock. It is also the chapter that most directly touches on the great contribution of engineering to our story. The science of thermodynamics, which has become our guide to the ultimate fate of the Universe, arose from considerations of the efficiency of steam engines in the nineteenth century and not a desire to peer out towards a possibly infinite future. In ‘Destiny’ we describe thermodynamics in detail, and show how this quintessentially nineteenth-century science allows us to speculate with some grounding in reality about events that will happen 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,

000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,

000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 years from now. Not bad for the pioneers of the age of steam.

So as we look to the future and survey the wonders of our universe, we discover that Einstein’s theory of gravity, our best description of the fabric of the Universe, predicts its demise inside black holes. The collapsing remnants of the most luminous stars represent the edge of our understanding of the laws of physics and therefore the edge of our understanding of the wonders of the Universe. This is exactly where every scientist wants to be. Science is a word that has many meanings; one might say science is the sum total of our knowledge of the Universe, the great library of the known, but the practice of science happens at the border between the known and the unknown. Standing on the shoulders of giants, we peer into the darkness with eyes opened not in fear but in wonder. The fervent hope of every scientist is that they glimpse something that not only requires a new scientific theory, but that requires the old theory to be replaced. Our great library is constantly being rewritten; there are no sacred tomes; there are no untouchable truths; there is no certainty; there is simply the best description we have of the Universe, based purely on our observations of its wonders.

The scientific project is ultimately modest: it doesn’t seek universal truths and it doesn’t seek absolutes, it simply seeks to understand – and therein lies its power and value. Science has given us the modern world, of that there can be no doubt. It has improved our lives beyond measure; increased life expectancy, decreased child mortality, eradicated many diseases and rendered many more impotent. It has given many of us the gift of time, freed us from the drudgery of mere survival and allowed us to open our minds and explore. Science is therefore a virtuous circle; its discoveries creating more time and wealth that we can, if we are wise, invest in further voyages of exploration and discovery. But for all its undoubted usefulness, I maintain that science is fuelled not by utilitarian desire but by curiosity. The exploration of the Universe and its wonders is as important as the search for new medical treatments, new energy sources or new technologies, because ultimately all these valuable advances rest on an understanding of the basic laws that govern everything in nature, from atoms to black holes and everything in between. This is why curiosity-driven science is the most valuable of pursuits, and this is why we must continue our journey into the darkness

Armed with a greater knowledge and understanding of our universe, and also with new technology and modern approaches to science, we can discover wonders of the Universe that would have remained hidden to us centuries ago. Galaxies such as the spiral-shaped Dwingeloo 1 have recently been found hidden behind the Milky Way. This discovery supports what we already know: that there are many more wonders out there in the Universe that we have yet to discover.

CHAPTER 1

MESSENGERS

THE STORY OF LIGHT

Throughout recorded history humans have looked up to the sky and searched for meaning in the heavens. The science of astronomy may now conjure thoughts of telescopes and planetary missions, but every modern moment of discovery has a heritage that stretches back thousands of years to the simplest of questions: what is out there? Light is the only connection we have with the Universe beyond our solar system, and the only connection our ancestors had with anything beyond Earth. Follow the light and we can journey from the confines of our planet to other worlds that orbit the Sun without ever dreaming of spacecraft. To look up is to look back in time, because the ancient beams of light are messengers from the Universe’s distant past. Now, in the twentieth century, we have learnt to read the story contained in this ancient light, and it tells of the origin of the Universe.

The spectacular remains and towering pillars of Karnak Temple are a testament to the Egyptian belief in the power and importance of the Amun-Re, the Sun God, in their daily life, and of the Sun itself.

Karnak Temple, home of Amun-Re, universal god, stands facing the Valley of the Kings across the Nile in the city of Luxor. In ancient times Luxor was known as Thebes and was the capital of Egypt during the opulent and powerful New Kingdom. At 3,500 years old, Karnak Temple is a wonder of engineering, with thousands of perfectly proportioned hieroglyphs, and an architectural masterpiece of ancient Egypt’s golden age; it is a place of profound power and beauty. Ten European cathedrals would fit within its walls; the Hypostyle Hall alone, an overwhelming valley of towering pillars that once held aloft a giant roof, could comfortably contain Notre Dame Cathedral.

Religious and ceremonial architecture has had many functions throughout human history. There is undoubtedly a political aspect – these monumental edifices serve to cement the power of those who control them – but to think of the great achievements of human civilisation in these terms alone would be to miss an important point. Karnak Temple is a reaction to something far more magnificent and ancient. The scale of the architecture forcibly wrenches the mind away from human concerns and towards a place beyond the merely terrestrial. Places like this can only be built by people who have an appropriate reverence for the Universe. Karnak is both a chronicle in stone and a bridge to the answer to the eternal question: what is out there? It is an observatory, a library and an expression carved out of the desert of cosmological curiosity and the desire to explore.

Egyptian religious mythology is rich and complex. With almost 1,500 known deities, countless temples and tombs and a detailed surviving literature, the mythology of the great civilisation of the Nile is considered the most sophisticated religious system ever devised. There is no such thing as a single story or tradition, partly because the dynastic period of Egyptian civilisation waxed and waned for over 3,000 years. However, central to both life and mythology are the waters of the Nile, the great provider for this desert civilisation. The annual floods created a fertile strip along the river that is strikingly visible when flying into Luxor from Cairo, although since 1970 the Aswan Dam has halted the ancient cycle of rising and falling waters and today the verdant banks are maintained by modern irrigation techniques. The rains still fall on the mountains south of Egypt during the summer, and before the dam they caused the waters of the Nile to rise and flood low-lying land until they cease in September and the waters recede, leaving life-giving fertile soils behind.

The dominance of the great river in Egyptian life, unsurprisingly, found its way into the heart of their religious tradition. The sky was seen as a vast ocean across which the gods journeyed in boats. Egyptian creation stories speak of an infinite primordial ocean out of which a single mound of earth arose. A lotus blossom emerged from this mound and gave birth to the Sun. In this tradition, each of the primordial elements is associated with a god. The original mound of earth is the god Tatenen, meaning ‘risen land’ (he also represented the fertile land that emerged from the Nile floods), while the lotus flower is the god Nefertem, the god of perfumes. Most important is the Sun God, born of the lotus blossom, who took on many forms but remained central to Egyptian religious thought for over 3,000 years. It was the Sun God who brought light to the cosmos, and with light came all of creation.

The power of the supreme god Amun-Re is felt everywhere at Karnak. Representations of him cover the walls; the carvings mostly depict him as human with a double-plumed crown of feathers alongside the Pharoah, but also in animal form as a ram.

The location and alignment of this impressive building, like everything else about it, has meaning. Egyptologists have evidence to support their belief that it was constructed as a sort of calendar; two columns frame the light of the sun as it rises on the winter solstice.

At Karnak, the Sun God reigns supreme as Amun-Re, a merger between the god Amun, the local deity of Thebes, and the ancient Sun God, Re. This tendency to merge gods is widespread in Egyptian mythology, and with the mergers comes increasing theological complexity. Amun can be seen as the hidden aspect of the Sun, sometimes associated with his voyage through the Underworld during the night. In the Egyptian Book of the Dead, Amun is referred to as the ‘eldest of the gods of the eastern sky’, symbolising his emergence as the solar deity at sunrise. As Amun-Re, he became the King of the Gods, and as Zeus-Ammon he survived into Greek and Roman times. Worship of Amun-Re as the supreme god became so widespread that the Egyptian religion became almost monotheistic during the New Kingdom. Amun-Re was said to exist in all things, and it was believed that he transcended the boundaries of space and time to be all-seeing and eternal. In this sense, he could be seen as a precursor to the gods of the Judeo-Christian and Islamic traditions.

The walls of Karnak Temple are literally covered with representations of Amun-Re, usually depicted in human form with a double-plumed crown of feathers – the precise meaning of which is unknown. He is most often seen with the Pharaoh, but he also appears at Karnak in animal form, as a ram.

The most spectacular tribute of all to Amun-Re, though, lies in Karnak’s orientation to the wider Universe. The Great Hypostyle Hall, the dominant feature of the temple, is aligned such that on 21 December, the winter solstice and shortest day in the Northern Hemisphere, the disc of the Sun rises between the great pillars and floods the space with light, which comes from a position directly over a small building inside which Amun-Re himself was thought to reside. Standing beside the towering stone columns watching the solstice sunrise is a powerful experience. It connects you directly with the names of the great pharaohs of ancient Egypt, because Amenophis III, Tutankhamen and Rameses II would have stood there to greet the rising December sun over three millennia ago.

The Sun rises at a different place on the horizon each morning because the Earth’s axis is tilted at 23.5 degrees to the plane of its orbit. This means that in winter in the Northern Hemisphere the Earth’s North Pole is tilted away from the Sun and the Sun stays low in the sky. As Earth moves around the Sun, the North Pole gradually tilts towards the Sun and the Sun takes a higher daily arc across the sky until midsummer, when it reaches its highest point. This gradual tilting back and forth throughout the year means that the point at which the Sun rises on the eastern horizon also moves each day. If you stand facing east, the most southerly rising point occurs at the winter solstice. The sunrise then gradually drifts northwards until it reaches its most northerly point at the summer solstice. The ancients wouldn’t have known the reason for this, of course, but they would have observed that at the solstices the sunrise point stops along the horizon for a few days, then reverses its path and drifts in the other direction. The solstices would have been unique times of year and important for a civilisation that revered the Sun as a god.

Standing in Karnak Temple watching the sunrise on this special midwinter day the alignment is obvious, but proving that ancient sites are aligned with events in the sky is difficult and controversial. This is because a temple the size of Karnak will always be aligned with something in the sky, simply because it has buildings that point in all directions! However, a key piece of evidence that convinced most Egyptologists that Karnak’s solstice alignment was intentional concerns the two columns on either side of the building in which Amun-Re resides – one to the left and one to the right when facing the rising Sun. These columns are delicately carved, and it is the inscriptions that suggest the sunrise alignment is deliberate. The left-hand column has an image of the Pharaoh embracing Amun-Re, and on one face are three carved papyrus stems – a plant that only grows along the northern reaches of the Nile. The right-hand column is similar in design, except the Pharaoh embraces Amun-Re wearing the crown of upper Egypt, which is south of Karnak. The three carved stems on this column are lotus blossoms, which only grow to the south.

It seems clear therefore that the columns are positioned and decorated to mark the compass directions around the temple, which is persuasive evidence that the heart of this building is aligned to capture the light from an important celestial event – the rising of the Sun in midwinter. It is a colossal representation of the details of our planet’s orientation and orbit around our nearby star.

The temple represents the fascination of the ancient Egyptians with the movement of the lights they saw in the sky. Their instinct to venerate them was pre-scientific, but the building also appears to enshrine a deepening awareness of the geometry of the cosmos. By observing the varying position of sunrise, an understanding of the Earth’s cycles and seasons developed, which provided essential information for planting and harvesting crops at optimum times. The development of more advanced agricultural techniques made civilisations more prosperous, ultimately giving them more time for thought, philosophy, mathematics and science. So astronomy began a virtuous cycle through which the quest to understand the heavens and their meaning lead to practical and intellectual riches beyond the imagination of the ancients.

Tasuta katkend on lõppenud.