Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

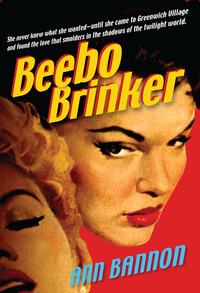

Loe raamatut: «Beebo Brinker»

“Looking back from the mid-80s to the distant 50s and 60s, let me share a thought with you. The books as they stand have 50s flaws. They are, in effect, the offspring of their special era, with its biases. But they speak truly of that time and place as I knew it. I would not write them today quite as I wrote them then. But I did write them then, of course. And if Beebo is really there for some of you—and Laura and Beth and the others—it’s because I stayed close to what felt real and right.” — ANN BANNON

Beebo Brinker

Ann Bannon

MILLS & BOON

Before you start reading, why not sign up?

Thank you for downloading this Mills & Boon book. If you want to hear about exclusive discounts, special offers and competitions, sign up to our email newsletter today!

Or simply visit

Mills & Boon emails are completely free to receive and you can unsubscribe at any time via the link in any email we send you.

Table of Contents

Cover

Excerpt

Title Page

Beebo Brinker

Endpages

Copyright

Beebo Brinker

Jack Mann had seen enough in his life to swear off surprise forever. He had seen the ports of the Pacific from the deck of a Navy hospital ship during World War II. He had helped patch the endless cut and bloodied bodies, torn every which way, some irreparably. He had seen the sensuous Melanesian girls, the bronzed bare-chested surfers on Hawaiian beaches, the sly stinking misery of the caves of Iwo Jima.

A medical corpsman gets an eyeful—and a noseful—of human wretchedness during a war. When it was over, Jack left the service with a vow to lead a quiet uncomplicated life, and never to hurt anybody by so much as a pinprick. It shot the bottom out of his plans to enter medical school, but he let them go without undue regret. He’d be well along in his thirties by the time he finished, and it didn’t seem worth it any more.

So he completed the course he started before the war: engineering. And after he got his degree he took a job in the New York office of a big Chicago construction firm as head of drafting.

During those war years, when Jack was holding heaving sailors over the head and labeling countless blood samples, he had fallen in love. It was a lousy affair, unhappy and violent. But peculiarly good now and then. Good enough to sell him on Love for a long time.

He organized his life around it. He earned his money to pamper whatever passion came his way. That was the only real value his bank account held for him; that, and helping stray people out of trouble, the way others help stray cats.

But by the time Jack reached his thirties, there had been too many who took advantage of his generosity to swindle him; his confidence to cuckold him; his affection to torment him. He turned cynic. There was hope in him still, but he buttoned it down under his skepticism.

He wanted to stabilize his life, settle down with one person and live out a long rewarding love. But Jack Mann could only love other men: boys, to be exact. Volatile, charming, will-o-the-wisp boys, who looked him up Friday, loved him Saturday, and left him Sunday. They couldn’t even spell “stabilize.”

His emotional differentness had given Jack a good eye for people, a knack for sizing them up fast. He usually knew what to expect from a boy after talking to him twenty or thirty minutes, and he had learned not to give in to the type who brought certain suffering—the type who couldn’t spell.

But Jack had also learned that he couldn’t live his life only for love. The less romantic he got about it, the clearer his view of life became. It didn’t make him happy, this cynicism. But it protected him from too much hurt, and gave him a sort of sour wit and wisdom.

Jack Mann was thirty-three years old, short in height, tall in mentality. He was slight but tough: big-shouldered for his size and deep-chested. His far-sighted eyes watched the world through a pair of magnifying lenses, set in tortoise-shell frames.

They were seeing sharply these days, for Jack was between lovers: bored and restless, but also healthy, wealthy, and on the wagon. When the new love came along—and it would—he would stay up most nights, blow his bankroll, and hit the bottle. It was nuts, but it happened every time. It seemed to preserve his lost illusions for a while, till the new “love” vanished and joined the countless old ones in his memory.

Jack lived in Greenwich Village, near the bottom of Manhattan. It was filled with aspiring young artists. Filled, too, with ambitious businessmen with wives and families, who played hob with the local bohemia. A rash of raids was in progress on the homosexual bar hangouts at the moment, with cops rousting respectable beards-and-sandals off their favorite park benches; hustling old dykes, who were Village fixtures for eons, off the streets so they wouldn’t offend the deodorized young middle-class wives.

Jack was pondering the problem one May evening as he came up the subway steps at 14th Street. At six o’clock the air was still violet-light. It was a good time for ambling through the winding streets he had come to know so well.

He tacked neatly in and out through the spring mixture of tourists and natives: young girls with new jobs and timid eyes; older girls with no jobs and knowing eyes; quiet sensitive boys having intimate beers together in small boites. Shops, clubs, shoe-box theaters. It always delighted him to see them, people and buildings both, blooming with the weather.

Jack stopped to buy some knockwurst and sauerkraut in a German delicatessen, eating them at the counter with an ale.

When he left, feeling sage and prosperous, he saw a handsome girl passing the shop, carrying a wicker suitcase in one hand. Her strong face and bewildered eyes contradicted each other. Jack followed a few feet behind her, intrigued. He had done this many a time, sometimes meeting the appealing person behind the face, sometimes losing the face forever in the swirling crowds.

The girl he was tailing appeared to be in her late teens, big-tall, with dark curly hair and blue eyes: Irish coloring, but not an Irish face. She walked with long firm strides, yet clearly did not know where she was. In her pocket was a yellow Guide to Greenwich Village with creased pages. Twice she stopped to consult it, comparing what she read to the unfamiliar milieu surrounding her.

A sitting duck for fast operators, Jack thought. But something wary in the way she held herself and eyed the crowd told him she knew that much herself. She was trying to defend herself against them by suspecting every passerby of ulterior motives.

At the first street comer she nearly collided with a small crop-haired butch, who said, “Hi, friend,” to her. The big girl stared for a moment, surprised and uncertain, afraid to answer. She moved on, crossing the street and detouring widely around a Beat with a fierce beard who sat guarding his gouaches, watching her pass with a curious who-are-you? look.

Jack was amused at the girl’s odd air of authority, the set of her chin, the strong rhythm of her walking. And yet, despite her efforts to look self-assured, she was clearly no native New Yorker. Her face, when he glimpsed it, was a map of confusion.

Rather abruptly, as if suddenly tired, she stopped, and Jack waited discreetly behind her, leaning against a railing and lighting a cigarette, watching her with a casual air.

She searched with travel-grimy hands for a cigarette in her pocket, but found only tobacco crumbs. Wearily she let herself sag against a shop window, evidently convinced it was silly to keep marching in the same direction, just because she had started out in it. Better to rest, to think a minute. Her gaze fell on Jack, who was studying her with a little smile. She looked square at him, and then her eyes dropped. He sensed something of her reaction: he was a strange man; she was a girl, forlorn and alone in a city she didn’t know. And probably too damn poor to squander money on cigarettes.

Jack strolled over to her, pulling a pack from his pocket and extending it with one cigarette bounced forward for her to take. She looked up, startled. She was four inches taller than Jack. There was a small pause and then she shook her head and looked away, afraid of him.

“You’d take it if I were somebody’s grandmother,” he kidded her. “Don’t hold it against me that I’m a man.”

She gave him a tentative smile.

“Come on, take it,” he urged.

She accepted one cigarette, but still he held the pack toward her. “Take ’em all. I have plenty. You look like you could use these.”

She obviously wanted to, but she said shyly in a round low voice, “Thanks, but I can’t pay you.”

Jack chuckled. “You’re a nice girl from a nice family,” he said. “Know how I know? Oh, it’s not because you want to pay for the pack.” She looked at him with guarded interest. “It’s because you’re afraid of me. No, it’s true. That’s the mark of a nice girl, sad to say. Men scare her. I can hear your mother telling you, ‘Dear, never take presents from a strange man.’ Right?”

She smiled at him. “Close enough,” she said softly, and inhaled some smoke with a look of relief.

“Well, consider this a loan,” he said, gesturing toward the cigarettes, and then he tucked them in her pocket next to the Guide. She jumped at the touch of his hand. He felt it but did not say anything. “You’re pretty new, aren’t you?” he said.

“I’m pretty used, if you want to know,” she said ruefully.

Jack laughed. “How old? Seventeen?”

“Do I look that young?” she asked, dismayed. There was intelligence in her regular features, but a pleasant country innocence, too. And she was uncommonly handsome with her black wavy hair and restless blue eyes.

“Do you have a name?” he asked.

“Do you?” she countered, instantly defensive.

He held out his hand affably and said, “I’m Jack Mann. Does that make you feel any better?”

She took his hand, cautiously at first, then gave it a firm shake. “Should it?” she said.

“Only if you live down here,” he answered. “Everybody knows I’m harmless.”

She seemed reassured. “I’m going to live here. I’m looking for a place now.” She paused as if embarrassed. “I do have a name: Beebo Brinker.”

He blinked. “Beebo?” he said.

“It used to be Betty Jean. But I couldn’t say it right when I was little.”

They smoked a moment in silence and then Beebo said, “I guess I’d better get going. I have to spend the night somewhere.” And she turned a sudden pink, realizing the inference Jack might draw from her remark. “Everybody” might know Jack down here, but Beebo wasn’t everybody. For all she knew he was harmless as a shark. The mere fact that he had a name wasn’t all that reassuring.

“Looks to me like you need some food first,” he said lightly. “There’s always a sack somewhere.”

“I don’t have much money.”

“Better to spend it on food,” he said. “Anyway, what the hell, I’ll treat you. There’s some good Wiener schnitzel about a block back.” He tried to take her wicker case to carry it for her, but she pulled away, offended as if his offer were a comment on her ability to take care of herself.

Jack stopped and laughed a little. “Look, my little friend,” he said kindly. “When I first hit New York I was as pea-green as you are. Somebody did this for me and let me save my few bucks for a room and job hunting. This is my way of paying him back. Ten years from now, you’ll do the same thing for the next guy. Fair?”

It was hard for her to resist. She was almost shaky hungry; she was worn out; she was lost. And Jack looked as kind as he was. It was a part of his success in salvaging people: they liked his face. It was homely, but in the good-humored amiable way that made him seem like an old friend in a matter of minutes.

Finally Beebo smiled at him. “Fair,” she said. “But I’ll pay you back, Jack. I will.”

They walked back to the German delicatessen, Beebo with a firm grip on her suitcase.

She finished her meal in ten minutes. Jack ordered another for her, over her protests, kidding her about her appetite.

“Jesus,” he said. “When did you eat last?”

“Fort Worth.”

“Indiana?” Jack stared.

“Yes. I ate three sandwiches in the rest room, on the train. That was yesterday.” Beebo drained her milk glass and put it on the table. The pneumatic little blonde waitress brought the second plateful. Jack, watching Beebo, who was watching the waitress, saw her wide blue eyes glide up and down the plump pink-uniformed body with curious interest. Beebo pulled back, holding her breath as the waitress leaned over her to set a basket of bread on the table, and there was a look of fear on her face.

Jack thought to himself, she’s afraid of her. Afraid of that bouncy little bitch. Afraid of … women?

When she had finished eating, Beebo glanced up at him. For all her physical sturdiness and arresting face, she was not a forward or a confident girl.

“You eat like a farm hand,” he chuckled.

“I should. I was raised in farm country,” she said, looking away from him. Her shyness beguiled him. “Thank you for the food.”

“My pleasure.” He observed her through a scrim of cigarette smoke. “If I weren’t afraid of scaring hell out of you, I’d ask you over to my place for a drink,” he said. She blanched. “I mean, a drink of milk,” he said.

“I don’t drink,” she told him apologetically, as if teetotaling were something hick-town and unsophisticated.

“Not even milk?”

“Not with strange men.”

“Am I really that strange?” he grinned, laughing at her again.

“Am I really that funny?” she demanded.

“No.” He reached over the table top unexpectedly and pressed her hand. She tried to jerk it away but he held it tight, surprising her with his strength. “You’re a lovely girl,” he said. It wasn’t suggestive or even romantic. He didn’t mean it to be. “You’re a sweet young kid and you’re lost and tired and frightened. You need one thing right now, Beebo, and the rest will take care of itself.”

“What’s that?” She retrieved her hand and tucked it behind her.

“A friend.”

She gazed at him, sizing him up, and then began to move from the booth.

“I’m no wolf,” Jack said, sliding after her. “Can’t you tell? I just like to help lost girls. I collect them.” And when she turned back with a frown of disbelief, he shrugged. “Everybody’s got to have a hobby.”

He bought some Dutch beer and sausage, paid the cashier, and walked with Beebo out the front door. On the pavement she stopped, swinging her wicker case around in front of her like a piece of fragile armor. Jack saw the defensive glint in her eyes.

“Okay, little lost friend,” he said. “You’re under no obligation to me. If this bothers you, the hell with it. Find yourself a hotel room, a park bench. I don’t care. Well … I care, but I don’t want to scare you any more.”

Beebo hesitated a moment, then held out her hand and shook his. “Thanks anyway, Jack. I’ll find you some day and pay you back,” she said. She looked as much afraid to leave him as to stay with him.

“So long, Beebo,” he said, dropping her hand. She walked away from him backwards a few steps so she could keep an eye on him, turned around and then turned back.

Jack smiled at her. “I’m afraid I’m just about your safest bet,” he said kindly. “If you knew how safe, you’d come along without a qualm.”

And when he smiled she had to answer him. “All right,” she said, still clutching her wicker bag in both hands. “But just so you’ll know: my father taught me how to fight.”

“Beebo, my dear,” he said as they began to walk toward his apartment, “you could probably throw me twenty feet through the air if you had to, but you won’t have to. I have no designs on you. Honest to God. I don’t even have a bunch of etchings to show you in my pad. Nothing but good talk and cold beer. And a bed.”

Beebo stopped in her tracks.

“Well, the bed is good and cold too,” he said. “God, you’re a scary one.”

“Did you go home to bed with the first stranger you met in New York?” she demanded.

“Sure,” he said. “Doesn’t everybody?”

She laughed at last, a full country sound that must have carried across the hay fields, and followed him again. He walked, hands in pockets, letting her curb her long stride to keep from getting ahead of him. But when he tried to take her arm at a corner, she shied away, determined to rely only on herself.

Jack unlocked the door of his small apartment, holding it with his foot while Beebo went in. The corridor outside was littered with buckets, planks, and ladders. “They’re redecorating the hall,” he explained. “We like to put on a good front in this rattrap.”

He headed for the kitchen with the bag of sausage and the beer, set them on the counter, and sprang himself a can of cold brew. “What do you want, Beebo? One of these?” He lifted the can. When she hesitated, he said, “You don’t really want that milk, do you?”

“Have you got something—weak?”

“Well, I’ve got something colorful,” he said. “I don’t know how weak it is.” He went down on his haunches in front of a small liquor chest and foraged in it for a minute. “Somebody gave me this stuff for Christmas and I’ve been trying to give it away ever since. Here we are.”

He took out an ornate bottle, broke the seal and pulled the cork, and got down a liqueur glass. When he up-ended the bottle, a rich green liquid came out, moving at about the speed of cod-liver oil and looking like some dollar-an-ounce shampoo for Park Avenue lovelies. The pungent fumes of peppermint penetrated every crack in the wall.

“What is it?” Beebo said, intimidated by the looks of it.

“Peppermint schnapps,” Jack said. “God. It’s even worse than I thought. Want to chicken out?”

“I grew up in a town full of German farmers,” she said. “I should take to schnapps like a kid to candy.”

Jack handed over the glass. “Okay, it’s your stomach. Just don’t get tanked on the stuff.”

“I just want a taste. You make me feel babyish about the milk.”

He picked up his beer and the schnapps bottle, and she followed him into the living room. “You can drink all the milk you want, honey,” he said, settling into a leather arm chair, “before the sun goes over the yardarm. After that, we switch to spirits.”

He turned on a phonograph nearby and turned the sound low. Beebo sat down a few feet from him on the floor, pulling her skirt primly over her knees. She seemed awkward in it, like a girl reared in jeans or jodhpurs. Jack studied her while she took a sip of the schnapps, and returned her smile when she looked up at him. “Good,” she said. “Like the sundaes we used to get after the Saturday afternoon movie.”

She was a strangely winning girl. Despite her size, her pink cheeks and firm-muscled limbs, she seemed to need caring for. At one moment she seemed wise and sad beyond her years, like a girl who has been forced to grow up in a hothouse hurry. At the next, she was a picture of rural naïveté that moved Jack; made him like her and want to help her.

She wore a sporty jacket, the kind with a gold thread emblem on the breast pocket; a man’s white shirt, open at the throat, tie-less and gray with travel dust; a straight tan cotton skirt that hugged her small hips; white socks and tennis shoes. Her short hair had been combed without the manufactured curls and varnished waves that marked so many teenagers. It was neat, but the natural curl was slowly fighting free of the imposed order.

Her eyes were an off-blue, and that was where the sadness showed. They darted around the room, moving constantly, searching the shadows, trying to assure her, visually at least, that there was nothing to fear.

“What are you doing here in New York, Beebo?” Jack asked her.

She looked into her glass and emptied it before she answered him. “Looking for a job,” she said. “Me and everybody else, I guess.”

“What kind of job?”

“I don’t know,” she said softly. “Could I have a little more of that stuff?” He handed the bottle down to her. “It’s not half as bad as it looks.”

“Did you have a job back home?” he asked.

“No. I—I just finished high school.”

“In the middle of May?” His brow puckered. “When I was in school they used to keep us there till June, at least.”

“Well, I—you see—it’s farm country,” she stammered. “They let kids out early for spring planting.”

“Jesus, honey, they gave that up in the last century.”

“Not the little towns,” she said, suddenly on guard.

Jack looked at his shoes, unwilling to distress her. “Your dad’s a farmer, then?” he said.

“No, a vet.” She was proud of it. “An animal doctor.”

“Oh. What was he planting in the middle of May—chickens?”

Beebo clamped her jaws together. He could see the muscles knot under her skin. “If they let the farmer’s kids out early, they have to let the vet’s kids out, too,” she said, trying to be calm. “Everyone at the same time.”

“Okay, don’t get mad,” he said and offered her a cigarette. She took it after a pause that verged on a sulk, but insisted on lighting it for herself. It evidently bothered her to let him perform the small masculine courtesies for her, as if they were an encroachment on her independence.

“So what did they teach you in high school? Typing? Shorthand?” Jack said. “What can you do?”

Beebo blew smoke through her nose and finally gave him a woeful smile. “I can castrate a hog,” she said. “I can deliver a calf. I can jump a horse and I can run like hell.” She made a small sardonic laugh deep in her throat. “God knows they need me in New York City.”

Jack patted her shoulder. “You’ll go straight to the top, honey,” he said. “But not here. Out west somewhere.”

“It has to be here, even if I have to dig ditches,” she said, and the wry amusement had left her. “I’m not going home.”

“Where’s home?”

“Wisconsin. A little farming town west of Milwaukee. Juniper Hill.”

“Lots of cheese, beer, and German burghers?” he said.

“Lots of mean-minded puritans,” she said bitterly. “Lots of hard hearts and empty heads. For me … lots of heartache and not much more.”

“Why?” he said gently.

She looked away, pouring some more schnapps for herself. Jack was glad she had a small glass.

“Why did you ditch Juniper Hill, Beebo?” he persisted.

“I—just got into some trouble and ran away. Old story.”

“And your parents disowned you?”

“No. I only have my father—my mother died years ago. My father wanted me to stay. But I’d had it.”

Jack saw her chin tremble and he got up and brought her a box of tissues. “Hell, I’m sorry,” he said. “I’m too nosy. I thought it might help to talk it out a little.”

“It might,” she conceded, “but not now.” She sat rigidly, trying to check her emotion. Jack admired her dignity. After a moment she added, “My father—is a damn good man. He loves me and he tries to understand me. He’s the only one who does.”

“You mean the only one in Juniper Hill,” Jack said. “I’m doing my damnedest to understand you too, Beebo.”

She relented a little from her stiff reserve and said, “I don’t know why you should, but—thanks.”

“There must be other people in your life who tried to help, honey,” he said. “Friends, sisters, brothers—”

“One brother,” she said acidly. “Everything I ever did was inside-out, ass-backwards, and dead wrong as far as Jim was concerned. I humiliated him and he hated me for it. Oh, I was no dreamboat. I know that. I deserved a wallop now and then. But not when I was down.”

“That’s the way things go between brothers and sisters,” Jack said. “They’re supposed to fight.”

“You don’t understand the reason.”

“Explain it to me, then.” Jack saw the tremor in her hand when she ditched her cigarette. He let her finish another glassful of schnapps, hoping it might relax her. Then he said, “Tell me the real reason why you left Juniper Hill.”

She answered at last in a dull voice, as if it didn’t matter any more who knew the truth. “I was kicked out of school.”

Jack studied her, perplexed. He would have been gently amused if she hadn’t seemed so stricken by it all. “Well, honey, it only happens to the best and the worst,” he said. “The worst get canned for being too stupid and the best for being too smart. They damn near kicked me out once.… I was one of the best.” He grinned.

“Best, worst, or—or different,” Beebo said. “I was different. I mean, I just didn’t fit in. I wasn’t like the rest. They didn’t want me around. I guess they felt threatened, as if I were a nudist or a vegetarian, or something. People don’t like you to be different. It scares them. They think maybe some of it will rub off on them, and they can’t imagine anything worse.”

“Than becoming a vegetarian?” he said and downed the rest of his beer to drown a chuckle. He set the glass on the floor by the leg of his chair. “Are you a vegetarian, Beebo?” She shook her head. “A nudist?”

“I’m just trying to make you understand,” she said, almost pleading, and there was a real beacon of fear shining through her troubled eyes.

Jack reached out his hand and held it toward her until she gave him one of hers. “Are you afraid to tell me, Beebo?” he said. “Are you ashamed of something? Something you did? Something you are?”

She reclaimed her hand and pulled a piece of tissue from her bag, trying to keep her back straight, her head high. But she folded suddenly around a sob, bending over to hold herself, comfort herself. Jack took her shoulders in his firm hands and said, “Whatever it is, you’ll lick it, honey. I’ll help you if you’ll let me. I’m an old hand at this sort of thing. I’ve been saving people from themselves for years. Sort of a sidewalk Dorothy Dix. I don’t know why, exactly. It just makes me feel good. I like to see somebody I like, learn to like himself. You’re a big, clean, healthy girl, Beebo. You’re handsome as hell. You’re bright and sensitive. I like you, and I’m pretty particular.”

She murmured inarticulately into her hands, trying to thank him, but he shushed her.

“Why don’t you like yourself?” he asked.

After a moment she stopped crying and wiped her face. She threw Jack a quick cautious look, wondering how much of her story she could risk with him. Perversely enough, his very kindness and patience scared her off. She was afraid that the truth would sicken him, alienate him from her. And at this forlorn low point in her life, she needed his friendship more than a bed or a cigarette or even food.

Jack caught something of the conflict going on within her. “Tell me what you can,” he said.

“My dad is a veterinarian,” she began in her low voice. “Everybody in Juniper Hill loved him. Till he started—drinking too much. But that wasn’t for a long time. In the beginning we were all very happy. Even after my mother died, we got along. My brother Jim and I were friends back in grade school.

“Dad taught us about animals. There wasn’t a job he couldn’t trust me with when it came to caring for a sick animal. And the past few years when he’s been—well, drunk so much of the time—I’ve done a lot of the surgery, too. I’m twice the vet my brother’ll ever be. Jim never did like it much. He went along because he was ashamed of his squeamishness. But whenever things got bloody or tough, he ducked out.

“But I got along fine with Dad. The one thing I always wanted was to live a good life for his sake. Be a credit to him. Be something wonderful. Be—a doctor. He was so proud of that. He understood, he helped me all he could.” She drained her glass again. “Some doctor I’ll be now,” she said. “A witch doctor, maybe.” She filled the glass and Jack said anxiously, “Whoa, easy there. You’re a milk drinker, remember?”

She ignored him. “At least I won’t be around to see Dad’s face when he realizes I’ll never make it to medical school,” Beebo said, the corners of her mouth turned down. “I hated to leave him, but I had to do it. It’s one thing to stick it out in a place where they don’t like you. It’s another to let yourself be destroyed.”

“So you think you’ve solved your problems by coming to the big city?” Jack asked her.

“Not all of them!” she retorted. “I’ll have to get work, I’ll have to find a place to live and all that. But I’ve solved the worst one, Jack.”

“Maybe you brought some of them with you,” he said. “You didn’t run as far away from Juniper Hill as you think. People are still people, no matter what the town. And Beebo is still Beebo. Do you think New Yorkers are wiser and better than the people in Juniper Hill, honey? Hell, no. They’re probably worse. The only difference is that here, you have a chance to be anonymous. Back home everybody knew who you were.”

Beebo threw him a sudden smile. “I don’t think there’s a single Jack Mann in all of Juniper Hill,” she said. “It was worth the trip to meet you.”

“Well, I’d like to think I’m that fascinating,” he said. “But you didn’t come to New York City to find Jack Mann, after all. You came to find Beebo Brinker. Yourself. Or are you one of those rare lucky ones who knows all there is to know about themselves by the time they’re seventeen?”

“Eighteen,” she corrected. “No, I’m not one of the lucky ones. Just one of the rare ones.” Inexplicably, it struck both of them funny and they laughed at each other. Beebo felt herself loose and pliable under the influence of the liqueur. It was exhilarating, a floating release that shrouded the pain and confusion of her flight from home and arrival in this cold new place. She was glad for Jack’s company, for his warmth and humor. “You must be good for me,” she told him. “Either you or the schnapps.”

Tasuta katkend on lõppenud.