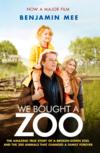

Loe raamatut: «We Bought a Zoo»

We Bought a Zoo

BENJAMIN MEE

The amazing true story of a broken-down zoo,

and the 200 animals that changed a family forever

Copyright

HarperNonFiction

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2008

© Benjamin Mee 2008

Benjamin Mee asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007274864

Ebook Edition © JANUARY 2009 ISBN: 9780007283767

Version: 2017-05-16

Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Copyright

Prologue

1 In the Beginning …

2 The Adventure Begins

3 The First Days

4 The Lean Months

5 Katherine

6 The New Crew

7 The Animals are Taking Over the Zoo

8 Spending the Money

9 Opening Day

Epilogue

About the Publisher

Prologue

Mum and I arrived at Dartmoor Wildlife Park in Devon for the first time as the new owners at around six o’clock on the evening of 20 October 2006, and stepped out of the car to the sound of wolves howling in the misty darkness. My brother Duncan had turned on every light in the house to welcome us, and each window beamed the message into the fog as he emerged from the front door to give me a bone-crushing bear hug. He was more gentle with mum. We had been delayed for an extra day in Leicester with the lawyers, as some last-minute paperwork failed to arrive in time and had to be sent up the M1 on a motorbike. Duncan had masterminded the movement of all mum’s furniture from Surrey in three vans, with eight men who had another job to go to the next day. The delay had meant a fraught stand-off on the drive of the park, with the previous owner’s lawyer eventually conceding that Duncan could unload the vans, but only into two rooms (one of them the fetid front kitchen) until the paperwork was completed.

So the three of us picked our way in wonderment through teetering towers of boxes, and into the flag-stoned kitchen, which was relatively uncluttered and we thought could make a good centre of operations. A huge old trestle table I had been hoarding in my parents’ garage for twenty years finally came into its own, and was erected in a room suited to its size. It’s still there as our dining-room table, but on this first night its symbolic value was immense. The back pantry had just flooded onto some boxes and carpets Duncan had managed to store there, so while he unblocked the drain outside I drove to a Chinese takeaway I’d spotted on the way from the A38, and we sat down to our first meal together in our new home. Our spirits were slightly shaky but elated and we laughed a lot in this cold dark chaotic house on that first night, and took inordinate comfort from the fact that at least we lived near a good Chinese.

That night, with mum safely in bed, Duncan and I stepped out into the misty park to try to get a grip on what we’d done. Everywhere the torch shone, eyes of different sizes blinked back at us, and without a clear idea of the layout of the park at this stage, the mystery of exactly what animals lurked behind them added greatly to the atmosphere. We knew where the tigers were, however, and made our way over to one of the enclosures which had been earmarked for replacement posts, to get a close look at what sort of deterioration we were up against. With no tigers in sight, we climbed over the stand-off barrier and began peering at the base of the structural wooden posts holding up the chain link fence by torchlight. We squatted down and became engrossed, prodding and scraping at the surface layers of rotted wood to find the harder core, in this instance, reassuringly near the surface. We decided it wasn’t so bad, but as we stood up were startled to see that all three tigers in the enclosure were now only a couple of feet away from where we were standing, ready to spring, staring intently at us. Like we were dinner.

It was fantastic. All three beasts – and they were such glorious beasts – had manoeuvred to within pawing distance of us without either of us noticing. Each animal was bigger than both of us put together, yet they’d moved silently. If this had been the jungle or, more accurately in this case, the Siberian Tundra, the first thing we’d have known about it would have been a large mouth round our necks. Tigers have special sensors along the front of their two-inch canines which can detect the pulse in your aorta. The first bite is to grab, then they take your pulse with their teeth, reposition them, and sink them in. As they held us in their icy glares, we were impressed. Eventually, one of these vast, muscular cats, acknowledging that, due to circumstances beyond their control (i.e. the fence between us), this had been a mere dress rehearsal, yawned, flashing those curved dagger canines, and looked away. We remained impressed.

As we walked back to the house, the wolves began their fraught night chorus, accompanied by the sound of owls – there were about 15 on site – the odd screech of an eagle, and the nocturnal danger call of the ververt monkeys as we walked past their cage. This was what it was all about, we felt. All we had to do now was work out what to do next.

It had been an incredible journey to get there. Though a new beginning, it also marked the end of a long and tortuous road, involving our whole family. My own part of the story starts in France.

Chapter One

In the Beginning …

L’Ancienne Bergerie, June 2004, and life was good. My wife Katherine and I had just made the final commitment to our new life by selling our London flat and buying two gorgeous golden-stone barns in the heat of the south of France, where we were living on baguettes, cheese and wine. The village we had settled into nestled between Nîmes and Avignon in Languedoc, the poor man’s Provence, an area with the lowest rainfall in the whole of France. I was writing a column for the Guardian on DIY, and two others in Grand Designs magazine, and I was also writing a book on humour in animals, a long-cherished project which, I found, required a lot of time in a conducive environment. And this was it.

Our two children, Ella and Milo, bilingual and sun burnished, frolicked with kittens in the safety of a large walled garden, chasing enormous grasshoppers together, pouncing amongst the long parched grass and seams of wheat, probably seeded from corn spilled from trailers when the barns were part of a working farm. Our huge dog Leon lay across the threshold of vast rusty gates, watching over us with the benign vigilance of an animal bred specifically for the purpose, panting happily in his work.

It was great. It was really beginning to feel like home. Our meagre 65 square metres of central London had translated into 1200 square metres of rural southern France, albeit slightly less well appointed and not so handy for Marks & Spencer, the South Bank, or the British Museum. But it had a summer which lasted from March to November, and locally grown wine which sells for £8 in Tesco cost three and a half euros at source. Well you had to, it was part of the local culture. Barbeques of fresh trout and salty sausages from the Cévennes mountains to our north, glasses of chilled rosé with ice which quickly melted in the heavy southern European heat. It was idyllic.

This perfect environment was achieved after about ten years of wriggling into the position, professionally and financially, where I could just afford to live like a peasant in a derelict barn in a village full of other much more wholesome peasants earning a living through honest farming. I was the mad Englishman; they were the slightly bemused French country folk, tolerant, kind, courteous, and yet inevitably hugely judgemental.

Katherine, whom I’d married that April after nine years together (I waited until she’d completely given up hope), was the darling of the village. Beautiful and thoughtful, polite, kind and gracious, she made a real effort to engage with and fit into village life. She actively learned the language, which she’d already studied at A level, to become proficient in local colloquial French, as well as her Parisian French, and the bureau-speak French of the admin-heavy state. She could josh with the art-gallery owner in the nearby town of Uzès about the exact tax form he had to fill in to acquire a sculpture by Elisabeth Frink – whom she also happened to have once met and interviewed – and complain with the best of the village mums about the complexities of the French medical system. My French, on the other hand, already at O-level grade D, probably made it to C while I was there, as I actively tried to block my mind from learning it in case it somehow further impeded the delivery of my already late book. I went to bed just as the farmers got up, and rarely interacted unless to trouble them for some badly expressed elementary questions about DIY. They preferred her.

But this idyll was not achieved without some cost. We had to sell our cherished shoebox-sized flat in London in order to buy our two beautiful barns, totally derelict, with floors of mud trampled with sheep dung. Without water or electricity we couldn’t move in straight away, so in the week we exchanged contracts internationally, we also moved locally within the village, from a rather lovely natural-stone summer let which was about to treble in price as the season began, to a far less desirable property on the main road through the village. This had no furniture and neither did we, having come to France nearly two years before with the intention of staying for six months. It would be fair to say that this was a stressful time.

So when Katherine started getting migraines and staring into the middle distance instead of being her usual tornado of admin-crunching, packing, sorting and labelling efficiency, I put it down to stress. ‘Go to the doctor’s, or go to your parents if you’re not going to be any help,’ I said, sympathetically. I should have known it was serious when she pulled out of a shopping trip (one of her favourite activities) to buy furniture for the children’s room, and we both experienced a frisson of anxiety when she slurred her words in the car on the way back from that trip. But a few phone calls to migraine-suffering friends assured us that this was well within the normal range of symptoms for this often stressrelated phenomenon.

Eventually she went to the doctor and I waited at home for her to return with some migraine-specific pain relief. Instead I got a phone call to say that the doctor wanted her to go for a brain scan, immediately, that night. At this stage I still wasn’t particularly anxious as the French are renowned hypochondriacs. If you go to the surgery with a runny nose the doctor will prescribe a carrier bag full of pharmaceuticals, usually involving suppositories. A brain scan seemed like a typical French overreaction; inconvenient, but it had to be done.

Katherine arranged for our friend Georgia to take her to the local hospital about twenty miles away, and I settled down again to wait for her to come back. And then I got the phone call no one ever expects. Georgia, sobbing, telling me it was serious. ‘They’ve found something,’ she kept saying. ‘You have to come down.’ At first I thought it must be a bad-taste joke, but the emotion in her voice was real.

In a daze I organized a neighbour to look after the children while I borrowed her unbelievably dilapidated Honda Civic and set off on the unfamiliar journey through the dark country roads. With one headlight working, no third or reverse gear and very poor brakes, I was conscious that it was possible to crash and injure myself badly if I wasn’t careful. I overshot one turning and had to get out and push the car back down the road, but I made it safely to the hospital and abandoned the decrepit vehicle in the empty car park.

Inside I relieved a tearful Georgia and did my best to reassure a pale and shocked Katherine. I was still hoping that there was some mistake, that there was a simple explanation which had been overlooked which would account for everything. But when I asked to see the scan, there indeed was a golf-ball-sized black lump nestling ominously in her left parietal lobe. A long time ago I did a degree in psychology, so the MRI images were not entirely alien to me, and my head reeled as I desperately tried to find some explanation which could account for this anomaly. But there wasn’t one.

We spent the night at the hospital bucking up each other’s morale. In the morning a helicopter took Katherine to Montpellier, our local (and probably the best) neuro unit in France. After our cosy night together, the reality of seeing her airlifted as an emergency patient to a distant neurological ward hit home hard. As I chased the copter down the autoroute the shock really began kicking in. I found my mind was ranging around, trying to get to grips with the situation so that I could barely make myself concentrate properly on driving. I slowed right down, and arrived an hour later at the car park for the enormous Gui de Chaulliac hospital complex to find there were no spaces. I ended up parking creatively, French style, along a sliver of kerb. A porter wagged a disapproving finger at me but I strode past him, by now in an unstoppable frame of mind, desperate to find Katherine. If he’d tried to stop me at that moment I think I would have broken his arm and directed him to X-ray. I was going to Neuro Urgence, fifth floor, and nothing was going to get in my way. It made me appreciate in that instant that you should never underestimate the emotional turmoil of people visiting hospitals. Normal rules did not apply as my priorities were completely refocused on finding Katherine and understanding what was going to happen next.

I found Katherine sitting up on a trolley bed, dressed in a yellow hospital gown, looking bewildered and confused. She looked so vulnerable, but noble, stoically cooperating with whatever was asked of her. Eventually we were told that an operation was scheduled for a few days’ time, during which high doses of steroids would reduce the inflammation around the tumour so that it could be taken out more easily.

Watching her being wheeled around the corridors, sitting up in her backless gown, looking around with quiet confused dignity, was probably the worst time. The logistics were over, we were in the right place, the children were being taken care of, and now we had to wait for three days and adjust to this new reality. I spent most of that time at the hospital with Katherine, or on the phone in the lobby dropping the bombshell on friends and family. The phone-calls all took a similar shape; breezy disbelief, followed by shock and often tears. After three days I was an old hand, and guided people through their stages as I broke the news.

Finally Friday arrived, and Katherine was prepared for theatre. I was allowed to accompany her to a waiting area outside the theatre. Typically French, it was beautiful with sunlight streaming into a modern atrium planted with trees whose red and brown leaves picked up the light and shone like stained glass. There was not much we could say to each other, and I kissed her goodbye not really knowing whether I would see her again, or if I did, how badly she might be affected by the operation.

At the last minute I asked the surgeon if I could watch the operation. As a former health writer I had been in operating theatres before, and I just wanted to understand exactly what was happening to her. Far from being perplexed, the surgeon was delighted. One of the best neurosurgeons in France, I am reasonably convinced that he had high-functioning Asperger’s Syndrome. For the first and last time in our conversations, he looked me in the eye and smiled, as if to say, ‘So you like tumours too?’, and excitedly introduced me to his team. The anaesthetist was much less impressed with the idea and looked visibly alarmed, so I immediately backed out, as I didn’t want anyone involved underperforming for any reason. The surgeon’s shoulders slumped, and he resumed his unsmiling efficiency.

In fact the operation was a complete success, and when I found Katherine in the high-dependency unit a few hours later she was conscious and smiling. But the surgeon told me immediately afterwards that he hadn’t liked the look of the tissue he’d removed. ‘It will come back,’ he warned. By then I was so relieved that she’d simply survived the operation that I let this information sit at the back of my head while I dealt with the aftermath of family, chemotherapy and radiotherapy for Katherine. Katherine received visitors, including the children, on the immaculate lawns studded with palm and pine trees outside her ward building. At first in a wheelchair, but then perched on the grass in dappled sunshine, her head bandages wrapped in a muted silk scarf, looking as beautiful and relaxed as ever, like the hostess of a rolling picnic. Our good friends Phil and Karen were holidaying in Bergerac, a seven-hour drive to the north, but they made the trip down to see us and it was very emotional to see our children playing with theirs as if nothing was happening in these otherwise idyllic surroundings.

After a few numbing days on the internet the inevitability of the tumour’s return was clear. The British and the American Medical Associations, and every global cancer research organization, and indeed every other organization I contacted, had the same message for someone with a diagnosis of a Grade 4 Glioblastoma: ‘I’m so sorry.’

I trawled my health contacts for good news about Katherine’s condition which hadn’t yet made the literature, but there wasn’t any. Median survival – the most statistically frequent survival time – is nine to ten months from diagnosis. The average is slightly different, but 50 per cent survive one year. 3 per cent of people diagnosed with Grade 4 tumours are alive after three years. It wasn’t looking good. This was heavy information, particularly as Katherine was bouncing back so well from her craniotomy to remove the tumour (given a rare 100 per cent excision rating), and the excellent French medical system was fast forwarding her onto its state-of-the-art radio therapy and chemotherapy programmes. The people who survived the longest with this condition are young healthy women with active minds – Katherine to a tee. And, despite the doom and gloom, there were several promising avenues of research, which could possibly come online within the timeframe of the next recurrence.

When Katherine came out of hospital, it was to a Tardislike, empty house in an incredibly supportive village. Her parents and brothers and sister were there, and on her first day back there was a knock at the window. It was Pascal, our neighbour, who unceremoniously passed through the window a dining-room table and six chairs, followed by a casserole dish with a hot meal in it. We tried to get back to normal, setting up an office in the dusty attic, working out the treatment regimes Katherine would have to follow, and working on the book of my DIY columns which Katherine was determined to continue designing. Meanwhile, a hundred yards up the road were our barns, an open-ended dream renovation project which could easily occupy us for the next decade, if we chose. All we lacked was the small detail of the money to restore them, but frankly at that time I was more concerned with giving Katherine the best possible quality of life, to make use of what the medical profession assured me was likely to be a short time. I tried not to believe it, and we lived month by month between MRI scans and blood tests, our confidence growing gingerly with each negative result.

Katherine was happiest working, and knowing the children were happy. With her brisk efficiency she set up her own office and began designing and pasting up layouts, colour samples and illustrations around her office, one floor down from mine. She also ran our French affairs, took the children to school, and kept in touch with the stream of well-wishers who contacted us and occasionally came to stay. I carried on with my columns and researching my animal book, which was often painfully slow over a rickety dial-up internet connection held together with gaffer tape, and subject to the vagaries of France Telecom’s ‘service’, which, with the largest corporate debt in Europe, makes British Telecom seem user friendly and efficient.

The children loved the barns, and we resolved to inhabit them in whatever way possible as soon as we could, so set about investing the last of our savings in building a small wooden chalet – still bigger than our former London flat – in the back of the capacious hanger. This was way beyond my meagre knowledge of DIY, and difficult for the amiable lunch-addicted French locals to understand, so we called for special help in the form of Karsan, an Anglo-Indian builder friend from London. Karsan is a jack of all trades and master of them all as well. As soon as he arrived he began pacing out the ground and demanded to be taken to the timber yard. Working solidly for 30 days straight, Karsan erected a viable two-bedroom dwelling complete with running water, a proper bathroom with a flushing toilet, and mains electricity, while I got in his way.

With some building-site experience, and four years as a writer on DIY, I was sure Karsan would be impressed with my wide knowledge, work ethic and broad selection of tools. But he wasn’t. ‘All your tools are unused,’ he observed. ‘Well, lightly used,’ I countered. ‘If someone came to work for me with these tools I would send them away,’ he said. ‘I am working all alone. Is there anyone in the village who can help me?’ he complained. ‘Er, I’m helping you Karsan,’ I said, and I was there every day lifting wood, cutting things to order, and doing my best to learn from this multi-skilled whirlwind master builder. Admittedly, I sometimes had to take a few hours in the day to keep the plates in the air with my writing work – national newspapers are extremely unsympathetic to delays in sending copy, and excuses like ‘I had to borrow a cement mixer from Monsieur Roget and translate for Karsan at the builder’s merchants’ just don’t cut it, I found. ‘I’m all alone,’ Karsan continued to lament, and so just before the month was out I finally managed to persuade a local French builder to help, who, three-hour lunch breaks and other commitments permitting, did work hard in the final fortnight. Our glamorous friend Georgia, one of the circle of English mums we tapped into after we arrived, also helped a lot, and much impressed Karsan with her genuine knowledge of plumbing, high heels and low-cut tops. They became best buddies, and Karsan began talking of setting up locally, ‘where you can drive like in India’, with Georgia doing his admin and translation. Somehow this idea was vetoed by Karsan’s wife.

When the wooden house was finished, the locals could not believe it. One even said ‘Sacré bleu.’ Some had been working for years on their own houses on patches of land around the village, which the new generation was expanding into. Rarely were any actually finished, however, apart from holiday homes commissioned by the Dutch, German and English expats, who often used outside labour or micromanaged the local masons to within an inch of their sanity until the job was actually done. This life/work balance with the emphasis firmly on life was one of the most enjoyable parts of living in the region, and perfectly suited my inner potterer, but it was also satisfying to show them a completed project built in the English way, in back-to-back 14-hour days with a quick cheese sandwich and a cup of tea for lunch.

We bade a fond farewell to Karsan and moved in to our new home, in the back of a big open barn, looking out over another, in a walled garden where the children could play with their dog, Leon, and their cats in safety, and where the back wall was a full adult’s Frisbee throw away. It was our first proper home since before the children were born, and we relished the space, and the chance to be working on our own home at last. Everywhere the eye fell there was a pressing amount to be done, however, and over the next summer we clad the house with insulation and installed broadband internet, and Katherine began her own vegetable garden, yielding succulent cherry tomatoes and raspberries. Figs dripped off our neighbour’s tree into our garden, wild garlic grew in the hedgerows around the vineyards, and melons lay in the fields often uncollected, creating a seemingly endless supply of luscious local produce. Walking the sun-baked dusty paths through the landscape ringing with cicadas with Leon every day brought back childhood memories of Corfu where our family spent several summers. Twisted olive trees appeared in planted rows, rather than the haphazard groves of Greece, but the lifestyle was the same, although now I was a grown-up with a family of my own. It was surreal, given the backdrop of Katherine’s illness, that everything was so perfect just as it went so horribly wrong.

We threw ourselves into enjoying life, and for me this meant exploring the local wildlife with the children. Most obviously different from the UK were the birds, brightly coloured and clearly used to spending more time in North Africa than their dowdy UK counterparts, whose plumage seems more adapted to perpetual autumn rather than the vivid colours of Marrakesh.

Twenty minutes away was the Camargue, whose rice paddies and salt flats are warm enough to sustain a year-round population of flamingoes, but I was determined not to get interested in birds. I once went on a ‘nature tour’ of Mull which turned out to be a twitchers’ tour. Frolicking otters were ignored in favour of surrounding a bush waiting for something called a redstart, an apparently unseasonal visiting reddish sparrow. That way madness lies.

Far more compelling, and often unavoidable, was the insect population, which hopped, crawled and reproduced all over the place. Crickets the size of mice sprang through the long grass entertaining the cats and the children who caught them for opposing reasons, the latter to try to feed, the former to eat. At night exotic-looking, and endangered, rhinoceros beetles lumbered across my path like little prehistoric tanks, fiercely brandishing their utterly useless horns, resembling more a triceratops than the relatively svelte rhinoceros. These entertaining beasts would stay with us for a few days, rattling around in a glass bowl containing soil, wood chips, and usually dandelion leaves, to see if we could mimic their natural habitat. But they did not make good pets, and invariably I released them in the night to the safety of the vineyards.

Other nighttime catches included big fat toads, always released on to a raft in the river in what became a formalized ceremony after school, and a hedgehog carried between two sticks and housed in a tin bath and fed on worms, until his escape into the compound three days later. It was only then I discovered that these amiable but flea-ridden and stinking creatures can carry rabies. But perhaps the most dramatic catch was an unknown snake, nearly a metre long, also transported using the stick method, and housed overnight in a suspended bowl in the sitting room, lidded, with holes for air. ‘What do you think of the snake?’ I asked Katherine proudly the next morning. ‘What snake?’ she replied. The bowl was empty. The snake had crawled out through a hole and dropped to the floor right next to where we were sleeping (on the sofa bed at that time) before sliding out under the door. I hoped. Katherine was not amused, and I resolved to be more careful about what I brought into the house.

Not all the local wildlife was harmless here. Adders (les vipères) are rife, and the brief is to call the fire brigade, or pompiers, who come ‘and dance around like little girls waving at it with sticks until it escapes’, according to Georgia who has witnessed this procedure. I once saw a vipère under a stone in the garden, and wore thick gloves and gingerly tapped every stone I ever moved afterwards. Killer hornets also occasionally buzzed into our lives like malevolent helicopter gunships, with the locals all agreeing that three stings would kill a man. My increasingly well-thumbed animal and insect encyclopedia revealed only that they were ‘potentially dangerous to humans’. Either way, whenever I saw one I adopted the full pompier procedure diligently.

Tasuta katkend on lõppenud.