Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «Little Town, Great Big Life»

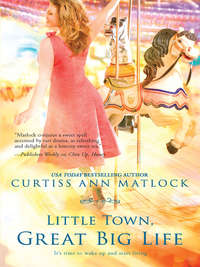

Little Town, Great Big Life

Little Town, Great Big Life

USA TODAY Bestselling Author

Curtiss Ann Matlock

This book is dedicated to all my readers—to each one of you who has over the years bought and enjoyed the Valentine series of books. For those of you who have written me: your letters have touched me, inspired me, given me smiles. Thank you from the bottom of my heart for sharing my Valentine people and their stories.

I am grateful to my agent, Margaret Ruley, and to sisters-in-heart Dee Nash and Deborah Chester for their guidance and support.

With this book, I say goodbye to writing my beloved Valentine. It has been a fine, adventuresome ride, but now it is time to change horses. It is, however, goodbye to the writing only. My characters are so real to me—Winston, Vella, Belinda, Corrine, Willie Lee and all the others—that I see them going on still in that small, sometimes dusty town somewhere in southwest Oklahoma. On quiet early mornings, I hear Winston’s voice over the radio…“Goood Mornin’, Valentinites!”

CONTENTS

PART ONE: EVERYBODY’S DREAMING BIG

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

PART TWO: IT TAKES FAITH, NOT EXPECTATIONS

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

PART THREE: BETWEEN BIRTH AND HEAVEN

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

EPILOGUE

PART ONE

CHAPTER 1

Winston Wakes Up the World

IN THE EARLY DARK HOUR JUST BEFORE DAWN, a lone figure—a man in slacks and wool sport coat, lapels pulled against the cold, carrying a duffel bag—walked along the black-topped ribbon of highway toward a town with a water tower lit up like a beacon.

Just then a sound brought him looking around behind him. Headlights approached.

The man hurried into the tall weeds and brush of the ditch. Crouching, he gazed at the darkness where his loafers were planted and hoped he did not get bit by something. A delivery truck of some sort went blowing past. As the red taillights grew small, the man returned to the highway. He brushed himself off and headed on toward the town.

Another fifteen minutes of walking and he could make out writing on the water tower: the word Valentine, with a bright red heart. Farther along, he came to a welcome sign, all neatly landscaped and also lit with lights. He stopped, staring at the sign for some minutes.

Welcome to Valentine, a Darn Good Place to Live!

Underneath this was:

Flag Town, U.S.A., Population 5,510 Friendly People and One Old Grump, 1995 Girls State Softball Championship, and Home of Brother Winston’s Home Folks Show at 1550 on the Radio Dial

Looking ahead, the man walked on with a bit of hope in his step.

The man would not be disappointed. The welcome sign pretty much said it all. Like a thousand other small towns across the country, Valentine was a friendly town that was right proud of itself and had reason to be. It was a place where the red-white-and-blue flew on many a home all year through and not just on the Fourth of July (as well as lots of University of Oklahoma flags and Oklahoma State flags, the Confederate flag, the Oklahoma flag and various seasonal flags). Prayer continued to be offered up at the beginning of rodeos, high-school football games and commencements, and nobody had yet brought a lawsuit, nor feared one, either. Mail could still be delivered with simply a name, city and state on the envelope. It was a place where people knew one another, many since birth, and everyone helped his neighbor. Even most of those who might fuss and fight with one another could be counted on in an emergency. The few poor souls who could not be counted on eventually ended up moving away. It was safe to say that most of the real crime was committed by people passing through. This exempted crimes of passion, which did happen on a more or less infrequent basis and seemed connected with the hot-weather months.

In the main, Valentine was the sort of small town about which a lot of sentimental stories are written and about which a lot of people who live in big cities dream, having the fantasy that once you moved there, all of your problems disappeared. This was not true, of course. As Winston Valentine, the self-appointed town oracle, often said, the problems of life—all the fear, greed, lust and jealousy, sickness and poverty—are connected to people, and are part of life on earth the world over.

It was true, however, that in a place like Valentine getting through life’s problems often was a little easier.

In Valentine, a person could walk most everywhere he needed to go, or find someone willing to drive him, or have things come to him. The IGA grocery, Blaine’s Drugstore, the Pizza Hut, the Main Street Café and even the Burger Barn provided delivery service, and for free to seniors or anyone with impaired health. Feeling blue could be counted as impaired health. When you needed to leave your car at the Texaco to have the oil changed or new tires put on, the manager, Larry Joe Darnell, or one of his helpers, would drive you home, or to work, and would even stop for you to pick up breakfast, lunch or your sister. When Margaret Wyatt’s husband ran off and left her the sole support of her teenage son, people made certain to go to her for alterations, whether they needed them or not, and for a number of years every bride in town had Miss Margaret make her wedding and bridesmaids’ dresses. It was a normal course of events in Valentine for neighbors to drop groceries on the front steps of those on hard times, and for extra to go into the church collection plates for certain families; small-town people knew about tax deductions. Yards got mowed, repairs made and overdue bills paid, often by that fellow Anonymous.

And in Valentine, when an elderly man no longer had legs strong enough to walk the sidewalk, and got his driver’s license revoked and his car taken away because of impudent daughters and meddlesome friends, he could still drive a riding lawn mower to get where he wanted to go.

This good idea came to Winston Valentine after a fitful night’s sleep in which he had dreamed of his long-dead wife, Coweta, and been left both yearning for her and relieved that her presence had only been a dream. Their marriage had been such a contrast, too.

Now in his tenth decade, Winston was a man with enough experience to understand that life itself was constant contrasts. He lay with his head cradled in his hands on the pillow, studying this matter as he stared at the faint pattern caused by the shine of the streetlight on the wall, while from the other side of it came muffled sounds—creak of the bed, a laugh and then a moan.

In the next room, the couple with whom he shared his house—Tate and Marilee Holloway—were doing what Winston had once enjoyed with his Coweta early of a morning.

Remembering, Winston’s spirits did a nosedive. He was long washed-up in that department. In fact, he was just about washed-up, period, as Coweta had put forth in the dream. He was ninety-two years old, and each morning he was a little surprised to wake up. That was his entire future: being surprised each morning to wake up.

It was at that particular moment, when his spirits were so low as to be in the bottom of the rut, an idea came upon him with such delightful force that his eyes popped wide. A grin swept his face.

“I’ll show ’em. I ain’t dead yet.”

His feet hit the cold floor with purpose. Holding to the bedpost, he straightened and stepped out quietly. Then, moving more quickly, he washed up and dressed smartly, as was his habit, in starched jeans and shirt, and an Irish sweater. Winston Valentine did not go around dressed “old,” as he called it.

After a minute’s rest in the chair beside the bedroom door, he picked up his polished boots, stepped into the hall in sock feet and soundlessly closed the door behind him.

He had forgotten his cane but would not turn back.

The hallway was dimly lit by a small light. The only bedroom door open was that of Willie Lee. Winston automatically glanced inside, saw that the boy had thrown off the blankets.

The little dog who lay at the foot of the bed lifted his head as Winston tiptoed into the room and gently pulled the blankets over the child, who slept the deep sleep of the pure in heart. When Winston left the room, the dog jumped down and followed soundlessly.

Gnarled hand holding tight to the handrail, Winston descended the stairs, knowing where to step to avoid the worst creaks. He located the small key that hung on the old rolltop desk in the alcove.

Then he went to the bench in the hall and tugged on his boots. Seeing the dog watching, he whispered, “Go on back up.”

The dog remained sitting, regarding him with a definite air of disapproval.

“Mr. Munro, you just keep your opinions to yourself.” Winston slipped into his coat and settled his felt Resistol on his head.

The dog still sat looking at him.

Winston went out into the crisp morning, closing the door on the dog, who turned and raced back down the hall and up the stairs, hopped onto the boy’s bed and over to peer through the window. His wet canine nose smeared fog on the glass. The old man came into view on the walkway, then disappeared through the small door of the garage.

Munro’s amber eyes remained fastened on the garage. His ears pricked at the faint sound of an engine. The small collie who lived next door came racing to the fence, barking his head off. Munro regarded such stupid action with disdain.

Moments later, a familiar green-and-yellow lawn mower came into view on the street, with the old man in the seat. Munro watched until machine and old man passed out of sight behind the big cedar tree in the neighbor’s yard. The sound faded, the stupid collie lay down and Munro reluctantly lay down on the bed. All was quiet.

Winston headed the lawn tractor along the street. The cold wind stung his nostrils, bit his bare hands, but his spirits soared. He imagined people in the houses hearing the mower engine and coming to their windows to look out.

Halfway along the street, it came to him, as he noted the limbs of a redbud tree that had just begun to sprout, that only the calendar said spring. The morning was yet cold and everyone’s house shut up tight. No one was going to hear him racing along the street.

Crossing the intersection with Porter Street, he hit a bump and had to grasp the steering wheel to keep from bouncing off the seat. He saw the newspaper headlines: Elderly Man Ends Life Plowing Mower into Telephone Pole.

But he was not about to downshift like some old candy-ass.

He kept his foot on the pedal and tightened his grip on the steering wheel. He wished he had thought of gloves.

He did slow when he came alongside the sheriff’s office at the corner of Church and Main streets. Maybe Sheriff Oakes was in this morning.

No one came to the door, though.

Driving down the middle of the empty highway, he was forced to slow a little. His hands were growing weak on the wheel, the old arthritis getting the best of him. He turned onto graveled Radio Lane and bounced along until he finally came to a stop outside the door of the concrete-block building beside Jim Rainwater’s black lowrider Chevrolet.

He had made it. And in all the distance traveled, nearly two miles, he had encountered no other person or vehicle. It was a deep disappointment.

He got himself off the mower, and was glad to have no witnesses. He moved like the rusted-up Tin Man. Inside the building, he might have leaned back against the door, but just then Jim Rainwater, coffee mug in hand, appeared from the sound booth. Winston brought himself up straight.

Jim Rainwater’s eyes widened. “Well, hey, Mr. Winston. Whatta ya’ doin’ here so early?” Jim Rainwater was a tall, slim young man in his twenties, a full-blood Chickasaw, and of a solemn nature. In a worried manner, as if he had missed something important, he checked his watch. “You know it isn’t even six?”

“Hey, yourself. I may be old, but I can still tell time. I got up early…what’s your excuse?” He sailed his hat toward the rack, but it missed.

Jim Rainwater picked up the hat, saying, “I always get here by now.”

“You need a life, young man.” Winston shrugged out of his heavy coat. “I thought I’d start us an early-mornin’ wake-up show.”

“Now, Mr. Winston, no one has said anything to me about that. Have you worked it out with Everett or Tate?”

Winston’s response to this was, “Why do you always call me mister?”

“Uh…I don’t know.”

“You don’t call any of those other fellas mister.”

Jim Rainwater gave a resigned sigh. “Mr…. Winston, what is it you want to do?”

“Aw, boy, don’t get your shorts in a wad. I’m not gonna step on Everett’s toes. He can have his show at seven, but we need somethin’ before that. A lot of those city stations start mornin’ shows at five. We’re losin’ audience share.”

“This is Valentine, Mr. Winston.”

“So it is, and it is time for a change. There’s folks here that need wakin’ up. I’ll thank you kindly for a cup of coffee,” he added as he made his way stiffly into the sound studio and dropped with some relief into his large swivel chair.

Jim Rainwater returned with the coffee. Winston sipped from the steaming mug that bore his name, stared at the microphone hanging over his desk and felt himself warm and his heart settle down.

“We’ll start up on the hour,” he told the young man.

Jim Rainwater shoved the weather forecast and a playlist in front of Winston. Slipping on his headphones, Winston positioned himself and adjusted the height of the microphone. He spoke in a moderate tone. “Testing…one, three, six, pick up sticks.” Retaining his own front teeth helped Winston to come over clear, and Jim Rainwater corrected a lot of the graveling of his voice with electronics.

The hour hand hit straight up. The young man pointed a finger at him.

Winston put his lips to the microphone and came out with, “GET UP, GET UP, YOU SLEE-PY-HEAD. GET UP AND GET YOUR BOD-Y FED!”

Jim Rainwater jumped and grabbed his earphones. Dumb-founded, he stared at Winston.

For his part, Winston, imagining his voice going out over the airwaves and entering radios in thousands of homes of people just waiting breathlessly for him, continued happily: “It’s six o’clock, ’n’ day is knockin’. GET UP, GET UP, YOU SLEE-PY-HEAD! GET UP AND GET YOUR BOD-Y FED!”

CHAPTER 2

1550 on the Radio Dial

Joy in the Morning!

IN ACTUALITY, WINSTON’S ASSUMPTION AS TO THE number of listeners was quite overblown. There were perhaps only two-dozen people with their radios tuned to the small local station. In the main, these were those whose cheap radios could not pick up the far-off stations, and mothers and school-teachers who listened while they drank strong coffee and waited for Jim Rainwater to provide the weather forecast and school lunch menu, followed by an hour of uninterrupted guitar instrumentals and alternative folk tunes of the sort that hardly any radio station played at any time, but which made a pleasant change from their little ones’ Disney radio or teenagers’ MTV.

At Winston’s shout, at least two people raced to turn off their radios, and three to turn up the volume, wondering if they had heard correctly. More than one person had been in the act of something they would not want anyone to know about and were jarred out of it.

One normally dour wife and mother, Rosalba Garcia, smiled a very rare smile, stamped out her cigarette and proceeded to the beds of her husband and three teenage sons, leaning over each head and shouting the singsong tune, “GET UP, GET UP, YOU SLEE-PY-HEAD!”

Inez Cooper, an early riser who was working on an agenda for the next meeting of the Methodist Ladies’ Circle, of which she was president, spewed her first sip of coffee all over her notes on that week’s scripture lesson about seeking peace. She jumped up to go tell her husband what Winston had done. Norman was also an early riser and out in his workshop. Inez got another shock when she caught Norman smoking a cigarette, which he was supposed to have given up three years ago, when the doctor told him that he had borderline emphysema and high enough cholesterol for an instant stroke. Winston had just ruined Inez’s morning all the way around. Norman wasn’t happy with him, either.

Julia Jenkins-Tinsley, early forties and an ardent jogger, had just settled her headset radio over her ears as she headed for the front door. Her overweight and much older husband, G. Juice Tinsley, was sprawled in his Fruit of the Looms on the couch where he usually slept these days, snoring like a freight train, and she was sick of hearing it. Winston’s voice hit Julia’s ears as she stepped out the door. She had the headset volume turned up and was about struck deaf.

Winston hollered out his reveille again at six-fifteen, like the chime on Big Ben.

Just after that, the phone rang back at his own house, where Corrine Pendley was already up and trying on her new, and first ever, Wonderbra, which she had bought, in secret, at a J. C. Penney sale, and viewing her sixteen-year-old breasts in the bra in front of her full-length mirror. At the ringing of the phone, she jumped, grabbed her robe and threw it around her as she raced to answer. In her mind, she imagined Aunt Marilee coming in and finding her in the bra. Aunt Marilee had ideas about what was age-proper, and she had been known to see through doors, too.

The caller was old Mr. Northrupt from across the street. “I want to talk to Tate!”

“Yes, sir,” was the only reply to that.

Checking to make certain her robe was securely tied, Corrine stepped out into the hall and almost ran into Papa Tate heading into the nursery, looking all tired and with his hair standing on end, as he often did in the morning. Handing him the phone, Corrine went to take care of her tiny niece, who was climbing over the toddler bed rails. She could hear Mr. Northrupt’s voice coming out of the phone. “Did you cancel my show? I think you could at least have told me. I didn’t have to find out by hearin’ Winston on there. Did you know he’s on there? Well, he is. He’s doin’ a reveille.”

Papa Tate calmed Mr. Northrupt down. “Winston’s just playin’ a prank. You still go on at seven.” He had to repeat this several times in different ways. Then Papa Tate hung up and told Corrine that he had changed his mind about the fun of owning a radio station.

Across the street, Everett Northrupt was not appeased. He stomped around, mad as a wet hen. He was the host of the 7:00 a.m. Everett in the Morning show. He liked that his show came right after Jim Rainwater playing a solid block of instrumental music, of a respectable nature. It was a perfect intro to Everett’s two hours of easy listening and intelligent commentary on the news and world at large. He considered his show an equal with NPR, and one of the rare venues in town for raising the consciousness of his listeners. Why, he had even interviewed by phone half a dozen state congressmen, one U.S. senator and a Pulitzer nominee (who happened to be station owner Tate Holloway).

Now old Winston was going to ruin all that. Winston stirred everything up with his rowdiness and wild musical leanings.

Emitting a few curses and condemnations as he pulled clothes from his neatly arranged drawers and closet, he woke his wife, Doris, who wanted to know what in the world was happening.

“It’s Winston…that’s who it is!” shouted Everett, jerking up his trousers. “Big windbag.”

His wife said, “Well, for heaven’s sake, shut up about it!” and threw a pillow at him.

Out at the edge of town, John Cole Berry was tiptoeing around his kitchen, attempting to slip out to a crucial early-morning business meeting without waking his light-sleeping wife, Emma, who was sure to want to make him breakfast. Emma thought food solved all problems. John Cole had just lifted the pot from the fancy stainless coffeemaker that Emma had recently bought, when some voice started yelling to get up and get his body fed.

Surprised, John Cole sloshed hot coffee all over his hand and the counter. He stared at the coffeemaker, a brand-new modern contraption that Emma had bought just the previous week, which did everything in the world, except make good coffee. It apparently had a radio in it. He went to punching buttons to shut it off. Why did a coffeemaker have a radio? Had Emma programmed it to say get fed? It would be just like her.

The radio, now playing music, shut off just as Emma called sleepily from the bedroom, “Honey…”

Grabbing his travel mug and sport coat, he slipped out the back door, leaving the telltale coffee spilled all over. He would tell her that he had missed cleaning it all. He could no longer see crap without his glasses. Somehow having the world by the tail at twenty-two had turned into the world having him by the tail at fifty-two.

Down in the ragged neighborhood behind the IGA grocery, seventeen-year-old Paris Miller, sleeping in the front seat of her old Chevy Impala because her grandfather had been on a drunken rampage the night before, had just turned on the car radio and snuggled back down into her sleeping bag. Her life was such that it was prudent to keep a sleeping bag in her car. All of a sudden a voice was shouting out.

Paris came up and hit her head on the steering wheel. Seeing stars, she fell back onto the seat, until, at last and with some relief, she figured out it was not her grandfather hollering at her. She thought maybe she had dreamed the yelling voice, because now Martina McBride was singing.

She snuggled back down into the warmth of the sleeping bag, dozing, until fifteen minutes later, when the yelling came out of the radio again. This time she recognized it as Mr. Winston’s voice. She started laughing and about peed her pants. Mr. Winston was always doing something funny.

She had to get up then, and the cold made her really have to hurry. She raced across the crunchy grass, into the musky-smelling kitchen, hopped over an empty vodka bottle and on to the bathroom. Glancing in the medicine-cabinet mirror, she was dismayed to see a bruise, good and purple, high up on her cheek, where she had not been able to duck fast enough the previous evening.

Down at the Main Street Café, owner Fayrene Gardner, tired and bleary-eyed after a lonely night kept company by a romance novel, a Xanax and two sleeping pills, was just coming down late from her apartment. Her foot was stretching for the bottom stair when Winston’s shout came crystal clear out of the portable radio sitting on the shelf above the sink, which happened to be level with her ear.

Fayrene popped out with “Jesus!” stumbled and would have plowed headlong into the ovens had not someone grabbed her.

Over at the grill, Woody Beauchamp, the cook, said, “Miss Fayrene, I’m gonna assume you’s prayin’. We wouldn’t want to give this visitor a poor impression, would we?”

Fayrene assured him that she had truly been praying. She was now, anyway, as she found herself gazing into the dark eyes of a handsome stranger, who had hold of her arm. Dear God, don’t let me make any more of a fool of myself in front of this handsome man.

The dark-eyed stranger grinned a wonderful grin, and Fayrene wondered if she might still be dreaming. Those sleeping pills were awfully strong.

Across the street, at Blaine’s Drugstore, which was on winter hours and not set to open for another hour, Belinda Blaine, who was not a morning person and not feeling well, either, was in the restroom peeing on a pregnancy-test strip. Somehow the radio on her desk just a few feet beyond the door, which she had not bothered to close, had been left on. (Probably by her cousin Arlo, when he had cleaned up the previous afternoon—she was going to smack him.) Hearing Winston’s familiar voice within two feet got her so discombobulated that she dropped the test strip in the toilet.

“Well, shoot.” She bent over and gazed into the toilet, trying to figure out the exact color of the test strip.

“Belinda? You in here?” It was her husband, Lyle, coming in the back door of the store.

She yanked up her reluctant panties and panty hose, while Lyle’s footsteps headed off to the front of the store. The panties and hose got all wadded together. Her mother swore no one should wear panties with panty hose, that that was the purpose of panty hose. As much as she hated to ever agree with her mother, this experience was about to convert Belinda to the no-panty practice.

Snatching up the test-kit box, she looked frantically around but found no satisfactory place to hide it. She ended up stuffing it into the waistband of her still-twisted panty hose.

“Of course I’m here. I was in the bathroom, Lyle,” she said as she strode out to the soda fountain.

Lyle was on his way back, and Belinda almost bumped into him.

She asked him where he thought she had been.

“Well, honey,” he said, with a bit of anxiety, “I saw your car out back, but didn’t see any lights turned on in front here, so I just wanted to check things out.”

Lyle was a deputy with the sheriff’s office next door. He had just gotten off night duty, and wanted coffee and to chat with her before he went home. Lyle listened to a lot of late-night radio when he was on patrol, which seemed to be encouraging morbid thoughts. Late-night talk shows were filled with a lot of conversation about scary things, such as UFO invaders, terrorist cells and, last night, the report of murderers who broke into the house of an innocent family up north and ended up killing them all.

Belinda, who made it a point to never listen to the news and really could have done without her husband telling her, ended up walking around with the test-kit box rubbing her skin while she got Lyle a cup of fresh coffee and tried to look interested in his report of world affairs and the idea of installing a security system at their home. Since she was already at the drugstore and had coffee made, she ended up opening early and got half a dozen customers coming in. At least Lyle had someone else to talk to, letting her off the hook.

All around a radius of the radio signal, roosters came out to crow, and skunks, armadillos and other annoying critters headed back to their dens, while early risers got up to let out the dog, let in the cat and look hopefully for the newspaper, which was often late. Word of Winston Valentine’s wake-up reveille spread, and Jim Rainwater began to take call after call, and to keep a running total of for or against.

Out front of the small cement-block radio station, Tate Holloway, who had received a number of telephone calls, and Everett Northrupt arrived at the same time. Everett, a short, rather bent man, was in such a state as to forget that Tate was the owner of the station and therefore his boss, and to jostle him for going first through the door. A man with a good sense of humor, Tate stood back and waved the older man on.

They reached the sound studio doorway just as Winston put his mouth to the microphone for his final reveille. “Gooood Mornin’, Valentinites! This is your last call. GET UP, GET UP, YOU SLEE-PY-HEAD. GET UP AND GET YOUR BOD-Y FED!”

This time Jim Rainwater over at the controls played a symbol and drum sound, and he and Winston grinned at each other. Jim had more fun working with Winston than he did any of the other volunteer disc jockeys.

Winston saw Everett Northrupt glaring in the doorway. His response was to lean into the microphone to say, “Well, folks, we’re leavin’ you now that we’ve gotcha woke up. Stay tuned for my good friend Everett, who will ease you into the day. Join me again for the Home Folks show at ten, and until then, remember Psalm 30, verse 5—For His anger is but for a moment, His favor is for life; Weeping may endure for a night, but a shout of joy comes in the mornin’.”

The men, all except Everett, chuckled.

Tasuta katkend on lõppenud.