Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «Consumed»

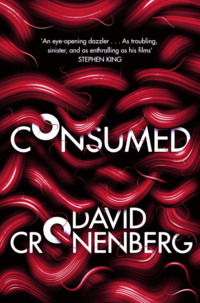

Consumed

DAVID CRONENBERG

Copyright

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate in 2014

First published in Canada by Hamish Hamilton in 2014

Copyright © David Cronenberg 2014

Cover by Jonathan Pelham

David Cronenberg asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and events either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or places or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007299157

Ebook edition © September 2014 ISBN: 9780007375240

Version: 2015-09-19

Dedication

For Carolyn

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

About the Author

About the Publisher

1

NAOMI WAS IN THE SCREEN. Or, more exactly, she was in the apartment in the QuickTime window in the screen, the small, shabby, scholarly apartment of Célestine and Aristide Arosteguy. She was there, sitting across from them as they sat side by side on an old couch—was it burgundy? was it corduroy?—talking to an off-camera interviewer. And with the white plastic earbuds in her ears, she was acoustically in the Arosteguy home as well. She felt the depth of the room and the three-dimensionality of the heads of this couple, sagacious heads with sensual faces, a matched pair, like brother and sister. She could smell the books jammed into the bookshelves behind them, feel the furious intellectual heat emanating from them. Everything in the frame was in focus—video did that, those small CCD or CMOS sensors; the nature of the medium, Naomi thought—and so the sense of depth into the room and into the books and the faces was intensified.

Célestine was talking, a Gauloise burning in her hand. Her fingernails were lacquered a purply red—or were they black? (the screen had a tendency to go magenta)—and her hair was up in an artfully messy bun with stray tendrils curling around her throat. “Well, yes, when you no longer have any desire, you are dead. Even desire for a product, a consumer item, is better than no desire at all. Desire for a camera, for instance, even a cheap one, a tawdry one, is enough to keep death at bay.” A wicked smile, an inhale of the cigarette with those lips. “If the desire is real, of course.” A catlike exhale of smoke, and a giggle.

A sixty-two-year-old woman, Célestine, but the European intellectual version of sixty-two, not the Midwestern American mall version. Naomi was amazed at Célestine’s lusciousness, her aura of style and drama, how her kinetic jewelry and her saucy slump on that couch seemed to blend together. She had never heard Célestine speak before—only now had a few interviews begun to emerge on the net, and only, of course, because of the murder. Célestine’s voice was husky and sensual, her English assured and playful, and lethally accurate. The dead woman intimidated Naomi.

Célestine turned languidly towards Aristide. Smoke tumbled from her mouth and nose and drifted over to him, like the passing of an evanescent baton. He took a breath to speak, inhaling the smoke, continuing her thought. “Even if you never get it, or, once having it, never use it. As long as you desire it. You can see this in the youngest babies. Their desire is fierce.” As he spoke these words, he began to stroke his tie, which was tucked into an elegant V-necked cashmere sweater. It was as though he were petting one of those fierce babies, and the gesture seemed to explain the blissful smile that suffused his face.

Célestine watched him for a moment, waited for the petting to stop, before she turned back to the unseen interviewer. “That’s why we say that the only authentic literature of the modern era is the owner’s manual.” Stretching forward towards the lens, revealing voluptuously freckled cleavage, Célestine fumbled for something off camera, then slumped back with a small, thick white booklet in her cigarette hand. She riffled through the pages, her face myopically close to the print—or was she smelling the paper, the ink?—until she found her page and began to read. “Auto-flash without red-eye reduction. Set this mode for taking pictures without people, or if you want to shoot right away without the red-eye function.” She laughed that rich, husky laugh, and repeated, this time with great drama, “Set this mode for taking pictures without people.” A shake of the head, eyes now closed to fully feel the richness of the words. “What author of the past century has produced more provocative and poignant writing than that?”

The window containing the Arosteguys shrank back to thumbnail size and became the lower left corner of a newscast window. The now tiny Arosteguys were still very relaxed and chatty, each picking up the conversation from the other like experienced handball players, but Naomi no longer heard what they said. Instead, it was the words of the overly earnest newscaster in the primary window that she heard. “It was in this very apartment of Célestine and Aristide Arosteguy, an apartment near the famous Sorbonne, of the University of Paris, that the grisly, butchered remains of a woman were found, a woman later identified as Célestine Arosteguy.” In the small window, the camera zoomed in on the amiably chatting Aristide. “Her husband, the renowned French philosopher and author Aristide Arosteguy, could not be found for questioning.” In one brutal cut Aristide disappeared, to be replaced by handheld, starkly front-lit shots of the tiny apartment’s kitchen, apparently taken at night. These soon swelled to full size and the newscaster’s window retreated to the upper right corner.

Forensic police wearing black surgical gloves were taking frosted plastic bags out of a fridge, photographing grimy pots and frying pans on the stove, sorting through dishes and cutlery. The miniature newscaster continued: “Sources wishing to remain unnamed have told us that there is evidence to suggest that parts of Célestine Arosteguy’s body were cooked on her own stove and eaten.”

Cut to a wide shot of an imposing municipal building subtitled “Préfecture de Police, Paris.” “Prefect of Police Auguste Vernier had this to say about the possible flight of Arosteguy from the country.” Cut to an interview with the strangely delicate, bespectacled prefect of police in what appeared to be a large hallway crammed with journalists. His French voice, emotionally intricate and intense, quickly faded to be replaced by a gravelly, less involved American one: “Mr. Arosteguy is a national treasure. So was Madame Célestine Moreau. It was a French ideal, the two of them, the philosopher couple. Her death is a national disaster.” A cutaway to the rambunctious crowd of journalists shouting questions, cameras and voice recorders bristling, then a return to the prefect. “Aristide Arosteguy left the country on a lecture tour of Asia three days before the remains of his wife were found. We have no specific reason at the moment to consider him a suspect in this crime, but naturally there are questions. It is true that we do not know exactly where he is. We are looking for him.”

The squawk of the carousel buzzer pulled Naomi out of the Préfecture de Police and back into the baggage claim arena of Charles de Gaulle Airport. As the conveyor belt lurched into action, the crowd of waiting passengers pressed forward. Somebody bumped Naomi’s laptop, sending it sliding down her shins, popping the earbuds out of her ears. She had been sitting on the edge of the carousel and had paid the price. Now she just managed to rescue her beloved MacBook Air by pivoting both feet up at the heels and catching the laptop with the toes of her sneakers. The Arosteguy report continued unperturbed in its window, but Naomi flipped the Air closed and put the Arosteguys to sleep for the time being.

NATHAN’S IPHONE RANG and he knew it was Naomi from the ringtone, the trill of an African tree frog that she had found somehow erotic and had emailed him. He was squatting on the floor of a damp, gritty, concrete back hallway of the Molnár Clinic, digging around in the camera bag in front of him, looking for something he suspected Naomi had taken, so it made sense that she would call him now, her extrasensory radar functioning in its usual freakish fashion. He kept digging with one hand, thumbing his phone on with the other. “Naomi, hey. Where are you?”

“I’m finally in Paris. I’m in a taxi heading for the Crillon. Where are you?”

“I’m in a slimy hallway at the Molnár Clinic in Budapest, and I’m looking in my camera bag for that 105mm macro lens that I bought in Frankfurt at the airport.”

The slightest pause, which, Nathan knew, did not have to do with Naomi’s possible guilt regarding the macro, but rather the fact that she was texting someone on her BlackBerry while talking to him. “Um … you won’t find it in your camera bag, because it’s on my camera. I borrowed it from you in Milan, remember? You were sure you weren’t going to need it.”

Nathan took a deep breath and cursed the moment he had convinced Naomi to switch from Canon to Nikon so that they could pool their hardware; brand passion was emotional glue for hard-core nerd couples. What a mistake. He stopped digging around in the bag. “Yeah. That’s what I thought. I was just hoping I hallucinated the whole handoff thing. I have lots of dreams about giving you my stuff.”

A snort from Naomi. “Is that really going to hang you up? You’ve suddenly discovered you need a macro?”

“I’m about to shoot an operation. I never imagined they’d let me in there, but they’re deliriously happy to have me document everything. I wanted the macro for my backup body. I’m sure there’ll be great weird Hungarian medical stuff to shoot huge close-ups of. Maybe not for the piece itself, but for reference. For our archives.”

Multitasking pause, a random interruption of conversational rhythm that drove Nathan crazy. But it was Naomi, so you ate it. “Sorry. Who knew?”

“Never mind. I’m sure your need is greater than mine.”

“My need is always greater than yours. I’m a very needy person. I wanted the macro to shoot portraits. I’ve set up some clandestine meetings with some French police types. I really want every pore in their faces.”

Nathan slumped back against the corridor’s damp wall. So he was stuck now with the 24–70mm zoom on his primary camera body, the D3. How close could that thing focus? It would probably be good enough. And he could crop the D3’s image files if he really needed to be close. Life with Naomi taught you to be resourceful. “Hey, honey, I’m surprised you actually want to get your hands dirty with real humans. What happened to net-surfing sources? What happened to the coziness of virtual journalism, where you never had to get out of your jammies? You wouldn’t have to be in Paris. You could be anywhere.”

“If I could be anywhere, I’d be in Paris.”

“Hey, and did you say the Crillon? Are you staying there or meeting somebody there?”

“Both.”

“Isn’t that crazy expensive?”

“I’ve got a secret contact. Won’t cost me un seul sou.”

Nathan immediately fired up his internal jealousy suppressors in the old familiar fashion. Not that Naomi’s secret contacts were always men, but they were all sketchy in some threatening way, dangerous. If you wanted to track her constantly tendriling social network, you’d have to apply a particularly sophisticated fractals program to her, mapping every minute of her day.

“Well, I guess that’s good,” he said, with a lack of enthusiasm meant to caution her.

“Yeah, it’s great,” said Naomi, not noticing.

A dimpled metal door at the far end of the hallway opened and the backlit figure of a man dressed for surgery beckoned to Nathan. “Come now to get dressed, mister. Dr. Molnár waits for you.”

Nathan nodded and lifted his hand in acknowledgment. The man flipped his own hand in a hurry-up gesture and disappeared, closing the door behind him.

“Okay, well, cancer calls. Gotta go. Tell me what’s up in two seconds or less.”

Another annoying multitasking pause—or was she just assembling her thoughts?—and then Naomi said, “On to some juicy French philosophical sex-killing murder-suicide cannibal thing. You?”

“Still the controversial Hungarian breast-cancer radioactive seed implant treatment thing. I adore you.”

“Je t’adore aussi. Call me. Bye.”

“Bye.” Nathan touched his phone off and hung his head. Just seal me up in this dank corridor and never find me again. There it was. There was always that moment of ferocious inner resistance, that fear of carrying the thing through, the resentment that action had to be taken, that risk and failure had to be confronted. But cancer called, and its voice was compelling.

IN HER SMALL BUT SUMPTUOUS attic room at the Hôtel de Crillon, Naomi was stretched out on an ornate chaise longue beside a short, narrow pair of French doors leading to a door-mat-sized balcony. From that balcony, she had already photographed the courtyard, with its intricate web of pigeon-repelling wires overhead, paying particular attention to details of decay, comme d’habitude. No matter how deluxe the hotel in Paris, you could count on the imprint of time to surprise you with wonderful textures. Now, having made her habitual nest of BlackBerry, cameras, iPad, compact and SD flashcards, lenses, tissue boxes, bags, pens and markers, makeup gear (minimal), cups and glasses bearing traces of coffee and various juices, chargers of all shapes and sizes, two laptops, chunky brushed-aluminum Nagra Kudelski digital audio recorder, notebooks and calendars and magazines, all of these anchored by her duffel bag and her backpack, Naomi reviewed her latest photos using Adobe Lightroom while watching a new video concerning the Arosteguys that had just surfaced on YouTube. And in another screen window, next to a photo of the hotel window’s rot-chewed frame with its faded white-and-greenstriped awning, striped also with streaks of rust from its delicate metal skeleton, was another intriguing display: a 360-degree panorama of the Arosteguy apartment, which Naomi idly controlled with her laptop’s trackpad, zooming and scrolling, in essence walking through the cramped, chaotic academics’ home.

There was the sofa shown in the earlier video, now patterned with blocks of sunlight streaming from a trio of small windows through which Naomi thought she could see a slice of the Sorbonne across the road. Behind the sofa were the densely populated bookshelves, but now swing around ninety degrees and more bookshelves, and piles of papers, letters, magazines, documents, littering every piece of furniture, including the kitchen sink, including the floor. Naomi smiled at the absence of cool electronics: a tape player, of all things; a small 4:3 tube TV set (could it actually be black and white?); and a phone with a cord. This pleased her, because it felt right for a hot French philosophy couple who were closer to Sartre and Beauvoir than Bernard-Henri Lévy and Arielle Dombasle. The Arosteguys seemed to belong to, at the latest, the 1950s. (She could see Simone Signoret, with her heavy sensuality, playing the role of Célestine in a movie, but only if she managed to project the intellect of Beauvoir; she wasn’t sure who would play Aristide.) To drill into their lives was to drill into the past, and that’s where Naomi wanted to go. She wasn’t looking for a mirror, not this time.

A paragraph below the panorama window confirmed that this was indeed the apartment before the murder, documented by a web-savvy student of Aristide’s—obviously using Panorama Tools and a fish-eye lens, Naomi noted—as part of a master’s thesis connecting the Evolutionary Consumerist philosophy of the Arosteguys with the couple’s own ascetic—relatively—lifestyle. The writer of that paragraph dryly noted that the wretched candidate, Hervé Blomqvist, had been denied his degree in the end. Naomi had come across an internet forum conducted by students of Célestine that had the tone of a sixties French New Wave movie. Blomqvist was a frequent contributor who positioned himself as a classic French bad boy along the lines of the actor Jean-Pierre Léaud. He hinted that as an undergraduate he had been the cherished lover of both Aristide and Célestine and was later punished for daring to use his place in the private lives of the Arosteguys to anchor what he confessed was “a pathetically thin and parasitical thesis.” Naomi emailed herself a note to connect with Blomqvist, a mnemonic technique that was the only one that seemed to work. Anything else got lost in the tangle of the Great Nest, as Nathan called the cloud of chaos that enveloped her.

The third window on Naomi’s screen was an interview shot in the oddly shaped basement kitchen of the couple who were responsible for the daily maintenance of the Arosteguys’ entire apartment block. The room was dominated by an immense concrete cylinder which suggested that half the casing of an exterior spiral staircase was bulging into their space. It was against this pale-green stuccoed column that a short, stout French woman and her shy, mustachioed husband stood speaking to an off-camera interviewer. The sound of the woman’s surprisingly youthful voice was soon mixed down to allow the voice of a translator to float over it. The translator’s voice, more mature, more matronly, seemed a better match for the woman’s face.

“Never,” said the translator. “No one could come between them, those two. Of course, they both had many affairs. They came here, the boys and girls, to their apartment just upstairs above us. We could sometimes hear them here behind us, laughing on the staircase, coming down as Mauricio and I had breakfast in the kitchen. He’s my husband.” A shy smile. “He’s Mexican.”

With a sweet, excited embarrassment, Mauricio waved directly at the camera. “Hello, hello,” he said in English.

The woman—only now, clumsily, identified as “Madame Tretikov, Maintenance” by a thick-fonted subtitle—continued. “They slept here. They lived here. Sometimes, yes, their lovers were students. But not always.” She shrugged. “For the students, it was a question of politics and philosophy, as always. The two together. They were in agreement. The Arosteguys explained it to me and Mauricio, and it seemed very correct, very nice.”

Naomi maximized the video window. With the screen filled, she could feel herself inside that kitchen, standing beside the camera, looking at that couple, the chipped enameled stove, the cupboards of moisture-swollen chipboard, damp kitchen towels spilling out of open cutlery drawers. She could smell the grease and the under-the-staircase dankness.

As if in response to the newly enlarged image, the cameraman zoomed slowly in to Madame’s face, zoomed because he saw moisture welling up in her eyes, like blood to a shark. Madame came through for her close-up, biting her quivering lip, tears spilling. Mercifully, the translator did not try to emulate the tremor in Madame’s voice.

“They were so brilliant, so exciting,” said Madame. “There could be no jealousy, no anger between them. They were like one person. She was sick, don’t you see? She was dying. I could see it in her eyes. Probably a brain tumor. She thought so hard all the time. Always writing, writing. I think it was a mercy killing. She asked him to kill her and he did. And then, of course, yes, he ate her.” With these words, Madame took a deep, stumbling breath, wiped her eyes with the threadbare dish cloth she had been holding throughout the interview, and smiled. The effect was startling to Naomi, who immediately began to analyze it in the email window she had left open in the corner of the screen. “He could not just leave her there, upstairs,” Madame continued. Her smile was beatific; she had a revelation to deliver. “He wanted to take as much of her with him as he could. So he ate her, and then he ran away with her inside him.”

THE MEDICAL GOGGLES were getting in the way. Nathan could barely see through the viewfinder of his ancient Nikon D3, the plastic lenses projecting too far from his eye, the goggles slewing and popping off his nose when he pressed the camera close, their elastic band pulling at his hair and crumpling his baby-blue paper surgical cap. “Everything changed after AIDS,” Dr. Molnár had just explained to him. “From then on, blood was more dangerous than shit. We realized you can’t afford to get it into your eyes, your tear ducts. So, we put on ski goggles in the operating theater and we schuss”—here he made slightly fey hip- and arm-twisting motions—“over the moguls of our patients’ bodies.” Now Dr. Molnár bent close to the Nagra SD voice recorder hanging around Nathan’s neck in its bondagestyle black-strapped leather case, and into its crustacean-like stereo cardioid microphone breathed, “Don’t be shy, Nathan. I’m notoriously vain. Get close. Fill your frame. That’s rule number one for a photographer, isn’t it? Fill your frame?”

“So they say,” said Nathan.

“Of course, you wrote to me that you were a medical journalist who was forced by the ‘swelling tide of media technology’ also to become a photographer and a videographer and a sound recordist, so perhaps you are now somewhat overwhelmed. I will guide you.”

Naomi had also, quite independently, bought one of the recorders, hers a now-discontinued ML model (it would kill her when she realized that), at Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport. Electronics stores in airports had become their neighborhood hangouts, although more often than not they weren’t there at the same time. It got to the point that they could sense traces of each other among the boxes of electric plug adapters and microSD flashcards. They would trade notes about the changing stock of lenses and point-n-shoots at Ferihegy, Schiphol, Da Vinci. And they would leave shopping lists for each other in emails and text messages, quoting best prices spotted and bettered.

“I’d really like to take the goggles off, Dr. Molnár. They weren’t designed for photographer-journalists.”

“Call me Zoltán, please, Nathan. And of course, take them off. You’ll have your huge brick of a camera in front of your eyes to protect you anyway.” Dr. Molnár laughed—rather a phlegmy, unhealthy laugh, Nathan thought—and swirled away to the other side of the operating table, past the array of screened and opened windows which let in the muted insect hum of the street below and a few splashes of early morning light that painted the room’s grimy and crumbling tiled walls.

Nathan took some shots of Dr. Molnár as he danced, and the good doctor’s body language conveyed his pleasure at being photographed. “Unusual to have open windows in an operating room,” Nathan couldn’t resist observing.

“Ah, well, our infrastructure here at the hospital is in disarray, you know, and so the air-conditioning is not functioning. Fortunately, we have the window option. This building is very old.” The doctor took up his position at the side of the operating table, flanked by two male assistants, and waved his arms over the table as though invoking spirits. “But you can see that the equipment itself is beautiful. First-rate, state-of-the-art.” Nathan dutifully began to take detail shots of the equipment, gradually leading him to the face of the patient herself, hidden behind a frame draped with surgical cloth, also baby blue, which separated her head from the rest of her body. The autonomous head seemed to be slumbering rather than anesthetized, and it was very beautiful. Short black hair, Slavic cheekbones, wide mouth, chin delicately pointed and cleft. For the moment, Nathan resisted taking her photograph.

“I notice you don’t seem to need to change lenses. The last photojournalist we had in here had a belt full of lenses. He made quite a lot of cinema twisting those lenses on and off his camera.”

“You’re very observant,” said Nathan. It was obvious that you could not compliment Dr. Molnár too much; it gave Nathan perverse satisfaction to find oblique ways to do it. “I sometimes do have a second camera body with a macrophotography lens. But these modern zooms have actually surpassed a lot of the old prime lenses in quality. Are you a student of photography?”

Dr. Molnár smiled behind his mask. “I have a half-interest in a little restaurant in a hotel downtown in Pest. You must come. You will be my special guest. The walls are covered with my photographs of nudes. I wouldn’t use that thing, though,” he said, pointing an oddly shaped forceps at the Nikon. “I’m strictly an analogue man. Medium-format film for me, and that’s that. It’s slow, it’s big and clumsy, and the details you see are exquisite. You can lick them. You can taste them.” The doctor’s mask bulged with the gestures his tongue was making to illustrate his approach to photography. He had already established in his first discussions with Nathan that it was the sensuality of surgery that had initially drawn him to the practice; sensuality was the guiding principle of every aspect of his life. He was making sure that Nathan wouldn’t forget it.

And now, in a very smooth segue—which Nathan thought of as particularly Hungarian—Dr. Molnár said, “Have you met our patient, Nathan? She’s from Slovenia. Une belle Slave.” Molnár peeked over the cloth barrier and spoke to the disconnected head with disarmingly conversational brio. “Dunja? Have you met Nathan? You signed a release form for him, and now he’s here with us in the operating theater. Why don’t you say hello?”

At first Nathan thought that the good doctor was teasing him; Molnár had emphasized the element of playfulness in his unique brand of surgery, and chatting with an unconscious patient would certainly qualify as Molnáresque. But to Nathan’s surprise Dunja’s eyes began to stutter open, she began working her tongue and lips as though she were thirsty, she took a quick little breath that was almost a yawn.

“Ah, there she is,” said Molnár. “My precious one. Hello, darling.” Nathan took a step backward in his slippery paper booties in order not to impede the strange, intimate flow between patient and doctor. Could she and her surgeon be having an affair? Could this really be written off as Hungarian bedside manner? Molnár touched his latex-bound fingertips to his masked mouth, then pressed the filtered kiss to Dunja’s lips. She giggled, then slipped away dreamily, then came back. “Talk to Nathan,” said Molnár, withdrawing with a bow. He had things to do.

Dunja struggled to focus on Nathan, a process so electromechanical that it seemed photographic. And then she said, “Oh, yes, take pictures of me like this. It’s cruel, but I want you to do that. Zoltán is very naughty. A naughty doctor. He came to interview me, and we spent quite a bit of time together in my hometown, which is”—another druggy giggle—“somewhere in Slovenia. I can’t remember it.”

“Ljubljana,” Molnár called out from the foot of the table, where he was sorting through instruments with his colleagues.

“Thank you, naughty doctor. You know, it’s your fault I can’t remember anything. You love to drug me.”

Nathan began to photograph Dunja’s face. She turned towards the camera like a sunflower. He regretted that he had decided not to use a video camera on his assignments, a fussy rejection that had to do with worries about media storage, peripherals, and other arcane techie calculations. Of course, if he’d been able to afford the new D4s, which could also record decent video … but he couldn’t keep up with the inexorable hot lava flow of technology, even though he desperately wanted to. Naomi was never so prissy. She just wasn’t wary. She’d already bought a new high-def no-name Chinese camcorder at Heathrow and had downloaded an obscure Asian editing program to work with its difficult files. Even if she’d had to shoot with her BlackBerry, she’d have caught, in all its coarse grain, the weird banter he had just heard. Oh, well. He had the voice recorder cooking, and he could append a sound file to each photograph using the camera’s microphone if push came to shove.

“Nathan? I think you are very beautiful,” said Dunja, just before she faded back into unconsciousness.

Nathan began to line up a 24mm low-angle shot with Dunja’s face in the foreground and her anesthetist—beefy, hairy, silent—behind her. “Nathan, forget about the face. It’s the breasts you want to see. Come over here beside me.” Nathan took his shot, then stood up and joined Dr. Molnár. Molnár pulled back the surgical cloth—orange, for some reason—covering Dunja’s chest. Her breasts were very full, and very blue and surreal in the cold light pouring from the lamp cluster which towered over the table. Capturing the effect of that light was exactly the reason Nathan rarely used flash, which would overpower the ambient light. Each breast had a dozen clear plastic wire-like tubes running into it, making it look like an umbrella that had been popped inside out by a strong wind. “Take pictures of those, would be better. If they’re good, I’ll print them and hang them in my restaurant.”

Tasuta katkend on lõppenud.