Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «Rewilding»

COPYRIGHT

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright in this compilation © David Woodfall 2019

Individual essays © Respective authors

All photography © David Woodfall 2019, with the exceptions of here (© Stephen Barlow) and here (© Ben Andrew).

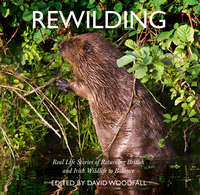

cover image: European Beaver, Bevis Trust, Carmarthenshire, Wales

David Woodfall asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this eBook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Source ISBN: 9780008300470

Ebook Edition © May 2019 ISBN: 9780008300487

Version: 2019-05-09

Sheep on snowscape, Conwy, Wales.

Definition of Rewilding

Rewilding is a contested idea, and people have different views on what exactly it should aim to achieve. For me, two elements of rewilding are crucial. The first is that natural ecological processes should be allowed to run their course, whereby new species can colonise an area, or a new habitat develop – which may, then, be replaced by a subsequent habitat. The second aspect is just as important, and this is that rewilding is something enacted by people, even where the intention is to leave nature to it. These people benefit from rewilding: this benefit might be spiritual, health-related or, indeed, economic. The overall goal is to kindle a more thoughtful approach to living on the Earth, and to support a move to more sustainable living.

This way of thinking has been around a long time. For example, in a book called Sharing the Work, Sparing the Planet by Anders Hayden, published in 1999, the author sets out a vision to enable us to achieve both greater sustainability and an enhanced quality of life. He argues that a lifestyle that is less rushed, more thoughtful and community-orientated could both enrich peoples’ lives at the same time as stopping us from degrading the life support which our planet now struggles to provide. This reflects my two themes: enriching nature and enriching people’s lives in the process.

The aim of this book is to show the many ways of being engaged in rewilding, and the great range of people who are helping to achieve it. I have visited a wide variety of places and spoken to many people, alone and in groups and within organisations, in the UK and Ireland. When I started out I had little idea how many people were actively rewilding. I recorded my impressions through photography – photographs that trace the changing landscape across thousands of years, and the human timeline from stone beehive huts to contemporary homelessness. The significance of rewilding is illuminated in essays written by professionals in the fields of wildlife conservation, recreation, education, agriculture and forestry, and by the people actively involved in making rewilding successful. I hope the book will contribute to our understanding of the potential opportunities and benefits that rewilding offers, and to provide a practical guide for new communities to strive for better connected, satisfying and sustainable lives.

FOR TESNI AND HELEN WITH LOVE

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Definition of Rewilding

Dedication

Introduction David Woodfall

Rewilding in Alladale Paul Lister

Rewilding in the Cairngorms National Park Will Boyd-Wallis

Restoring the Caledonian Forest Doug Gilbert

Carrifran Wildwood Philip Ashmole

Rewilding and Nature Agencies Robbie Bridson

Wild Nephin National Park Susan Callaghan

A Wetland Wilderness Catherine Farrell.

Rewilding the Marches Mosses Joan Daniels

Kielder’s Wilder Side Mike Pratt

Minimum-Intervention Woodland Reserves Keith Kirby.

Wild Ennerdale: Shaping the‘Future Natural’ Rachel Oakley

Epping Forest: A Wildwood? Judith Adams

The Burren: History of the Landscape Richard Moles

Red Squirrel Craig Shuttleworth

Rewilding Oxwich NNR Nick Edwards

Cabragh Wetlands Tom Gallagher

Lough Carra Chris Huxley

Time is Running Out Drew Love-Jones & Nicholas Fox.

The North Atlantic Salmon Allan Cuthbert

Riverine Integrity William Rawling

Moorland Geoff Morries

Reflections on the Summit to Sea Project Rebecca Wrigley

The South Downs Phil Belden

Landscape-scale Conservation of Butterflies and Moths Russel Hobson

Rewilding in the Context of the Conservation of Saproxylic Invertebrates Keith Alexander

Great Bustards David Waters

Rewilding Bumblebees Dave Goulson

New House Hay Meadows Martin Davies

Pigs Breed Purple Emperors Isabella Tree

Pant Glas Nick Fenwick

The Pontbren Project Wyn Williams

Lynbreck Croft Sandra & Lynn Cassells

South View Farm Sam & Sue Sykes

Rewilding in My Corner of Epping Forest Robin Harman

Prayer for Red Kites at Gleadless Martin Simpson

Species Introductions Matthew Ellis

Steart Marshes Tim McGrath

Whiteford Primary Slack Nick Edwards

Seashore Richard Harrington

Little Terns David Woodfall

Rewilding at the Coast Phil Dyke

Machair Derek Robertson

Rewilding Whales Simon Berrow

Rewilding Notes on Forest Gardens Mike Pope

The ‘Wilding’ of Gardens Marc Carlton & Nigel Lees

Vetch Community Garden Susan Bayliss

Rewilding: My Hedgehog Story Tracy Pierce

Rewilding Cities Scott Ferguson

Colliery Spoil Biodiversity Liam Olds

The Place of Rewilding in the Wider Context of Sustainability Richard Moles

Rewilding the Law Mumta Ito

Homeless Siobhan Davies

Rewilding Reborn Em Mackie

Rewilding of the Heart Bruce Parry

Conclusion David Woodfall

Acknowledgements

About the Book

About the Author

About the Publisher

Colonising silver birch in glaciated valley, Alladale.

Introduction

David Woodfall

Following the end of the last Ice Age 10,000 years ago, Britain and Ireland began to colonise with birch and oak which, apart from mountain tops, became established in all of our islands. Rewilding, essentially a new concept, is the return to allowing nature to take its own course and carpet our islands once more in natural vegetation and its associated fauna. During the Mesolithic period (15,000–5,000 bce) this native forest was considerably modified by burning and felling. By the Middle Ages (500 ce onwards) the wildwood had been replaced by a mosaic of cultural landscapes, created by an ever-increasing population. The Enclosure Acts of the eighteenth century were swiftly followed by the Industrial Revolution, with its increasing demands on mineral and timber resources, and further modified our landscapes. Landscapes became empty of all of our major predators, such as wolves, and landscape modifiers such as the beaver. While our cultural landscapes contained wonderful chalk grassland grazed by huge flocks of sheep, numerous heathlands grazed by cattle and diminishing peat bogs harvested by crofters in the north and west, these landscapes were unrecognisable from their native state, much of their diversity and richness gradually stripped away. During the Industrial Revolution there was a rapid reduction in the number of people employed on the land and a consequent decline of rural communities. There were changes, too, affecting limestone pavements, peatbogs – a reduction of sheep farming led to the depletion of chalk grassland. The last time our islands possessed any degree of biological richness was the 1930s, a richness that disappeared swiftly during the 1940s when World War II interrupted food imports, leading to a massive increase in lands given over to arable crops.

By the 1960s only a handful of intensively managed nature reserves contained a fraction of our previous flora and fauna, often isolated islands in an extensive agricultural prairie, where food production was continually supported by pesticides and chemical fertilisers, further diminishing our wildlife – the future of peregrine falcons were threatened by the build-up of toxins in the food chain. In the US, scientists such as Rachel Carson began to draw the public’s attention to such concerns and the environmental movement was born. This has subsequently led to the evolution of the rewilding movement, which I would define as allowing the natural succession from open ground to forest to take place, much in the way it happened 10,000 years ago. Essentially, to allow the landscape to develop in an organic way, opening up the full range of available niches for local species. However, much of the landscape of the UK and Ireland has been so severely modified that in many cases it is a challenge to allow rewilding to take place, as this process can lead to a short-term reduction in the existing diversity. In effect, the decision on the part of conservation organisations to cease management is a form of management in itself. Many of the priorities in conservation previously seen as set in stone will have to be carefully reconsidered. Further complications emerge from the significant changes being wrought on our landscapes, ecology and ourselves by climate change.

Dinosaur footprint, Severn Estuary.

By the modern age, most of the significant apex, ‘game changers’ within our flora and fauna, were now absent – in parallel with a naturally developing climax vegetation, it was deemed necessary to reintroduce many of the key animals which significantly affect the ecology of our landscapes. These include beavers, lynx, sea eagles, and red kites: species that will help stimulate and revive ecological processes that have been absent from our lands for thousands of years. The introduction of beavers could have a significant effect on reducing the flooding of agriculture areas and towns, something that appears to have increased in both intensity and frequency. Species such as sea eagle and red kite have already demonstrated that their increased presence can have a significant beneficial effect on tourism at both a local and national level.

This work has been carried out by inspired individuals, scientists and a growing number of NGO organisations, who are working with the government conservation agencies to help negotiate with landowners, carry out research and conduct trials with reintroduced species to ensure that such populations are sustainable and equitable among our highly managed islands. In addition, rewilding calls for a greatly reduced grazing regime in our uplands by both deer and sheep, and a general reduction in the grazing of our grassland ecosystems where appropriate to increase both plant and invertebrate populations, which in turn will greatly increase our mammal and bird populations. Due notice will have to be given to our ‘cultural habitats’, e.g. downland, which have evolved through our grazing regimes. Also both the significance and value of our post-industrial sites will have to be given greater recognition as we are blessed with large numbers of places that are great examples of the beneficial effect of rewilding, without us doing anything active at all. The reduction in fishing through a system of quotas, during the last ten years, has once again made the North Sea a place in which to fish sustainably, and the introduction of many wind turbines has had the effect of creating ‘artificial reefs’ which have further increased marine diversity. This is nowhere better demonstrated than the huge growth in cetacean and grey seal populations throughout Britain and Ireland. In turn this has attracted significant populations of killer whale. The changing sea temperatures around our coasts, due to changes in the jet stream, are also enhancing our whale and dolphin populations. Tuna weighing up to 230 kg (500 lb) have been caught off the Hebridean island of St Kilda, demonstrating that our seas, too, can be rewilded.

Our agricultural landscapes, even more so than the native habitats, have the potential for great change through rewilding. Our agriculture has been heavily subsidised through the European Economic Union (via Common Agricultural Payments), since the 1970s, and this has had a profound effect on both the landscapes themselves and their biodiversity. We are about to leave Europe and at the very least this is going to produce uncertainty for our agricultural landscapes. The most likely outcome of this will be that large areas of land will not be cultivated as intensively as previously. On the other hand, financial conglomerates, pension funds and extremely rich individuals may well buy up aggregations of small farms and produce ‘super farms’, leading to even greater insensitive management of our landscapes. The first of these outcomes ought to give the opportunity for a theory like rewilding to really flourish, allowing for many natural processes to take hold once more, rather than the more manicured effects of conservation that have been attempted so far. We have reached a point in our islands’ evolution where our growing understanding of rewilding has the realistic prospect of gaining both political and popular support. This has been achieved, in part, by the rapid growth of environmental education, and the popularity of TV and radio programmes by such people as David Attenborough – informing and enthralling the public with the ‘natural world’. This in turn has inspired countless individuals, paid and voluntary, to get involved in disparate conservation projects employing both species introduction and the development of more naturally developing climax vegetation communities. Rewilding has arrived and I feel that now is the right time to publish a book highlighting all the wonderful organisations and inspired individuals who are making the UK and Ireland such a biologically rich series of islands once again.

Mawddach Estuary, Snowdonia NP, Gwynedd.

Red deer stag at Alladale.

Rewilding in Alladale

Paul Lister

I spent my childhood growing up in north London and at a West Country boarding school, with simply no family connection to Scotland. My first trip north of the boarder was at the age of 23 in 1982 when my father, Noel, decided to take Mum and me on a trip to Argyll and Perthshire to look at some commercial forestry opportunities, on a cold, bleak and wet day. We were shown around by Fenning Welstead of the land agents John Clegg, and Des Dougan, a local deer stalker working for the Forestry Commission. After the decision was taken to invest, Des and I struck a chord and he invited me hind stalking.

For the following ten or so years, I met up with Des once or twice a year in a number of locations to help (or hinder) in the culling of red deer hinds and the odd invasive sika. When I first pulled the trigger all those years ago, I wondered what the sport was all about – why was it necessary to shoot so many deer? In my usually inquisitive way, I asked many questions and began to better understand the sorry state of the UK’s environment and especially the negative effects on wildlife. Most noticeably, the missing carnivores whose task, until driven to extinction, was to keep browsing deer numbers in check, which allowed native forests to regenerate and create a natural balance. Sadly, for a multitude of reasons, the vast majority the UK’s native woodland has been felled or burned over the last millennia; with trees gone, sheep and deer took over. Landowners/managers had little tolerance for large carnivores and their threat to livestock and they all soon vanished.

In the mid-1990s Roy Dennis introduced me to Christoph Promberger, a German ecologist who as working for the, now defunct, Munich Wildlife Society in ‘post-communist’ Romania. Two weeks later I set off to meet Christoph and his two socialised wolves, rescued from a fur farm about to close. In the middle of the wild and pristine snowy Carpathian mountains, I learned about a unique and unspoilt corner of Europe; a place lost in time and that had never suffered from mass industrialisation, like so many other countries in Europe. The incredible biodiverse nature of Romania blew my mind and made me realise just how much we had lost in Western Europe, and even more so in the Scottish Highlands. It’s really not difficult to imagine why the UK’s future King has chosen to spend his annual spring holidays in rural Romania, where he owns a home in a remote village, three hours from the nearest airport.

In my mid-forties, and with over twenty years in the furniture business, my mentor and father suffered a severe stroke, which shook our family and left me reflecting on what my life was all about. After some months of reflection and soul searching, I decided that, rather than be a part of the growing environmental problem, I wanted to be part of the solution. After decades of thinking about Britain’s bleak and desert-like environment, I decided to look for a Highland estate to rewild, whilst also establishing The European Nature Trust (TENT), a charity which now supports conservation and wildlife initiatives in Romania, Italy, Spain and Scotland.

After a couple of years and a stringent ‘must-have’ list, Alladale, a sleepy, stunning and remote deer-stalking estate, was purchased with the sole intention of rewilding. Some 15 years on, as the custodians of Alladale Wilderness Reserve (AWR) we have planted almost a million native trees, mainly in the riparian areas, to help mitigate flooding, prevent river bank erosion, provide food and shade for the salmon and trout, while also acting as a significant carbon sequester! Around 50 years ago the Scottish government naively believed landowners should be incentivised to drain peatlands, which would increase the amount of land available for livestock grazing. The resulting consequence was a huge release of carbon into the atmosphere. To counter this, and in partnership with the finance firm ICAP, we pioneered the restoration of our peatlands by blocking 20 km of hill drains. Our restorative actions have now led to newly moistened peat with live sphagnum moss, which once more acts as a massive carbon sequester.

While much of the discussion centred around Alladale has been about large carnivores, we have been busy with other less controversial species. In 2013, with support of TENT and in partnership with Highland Foundation for Wildlife, we released 36 red squirrels on Alladale and three neighbouring estates. The project has been a huge success, with hundreds of squirrels now spread far and wide, bringing smiles to neighbours and visitors alike. In addition we have a small collection of breeding wildcats which will be used to stock a larger-scale breed and release centre, now being planned by the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland (RZSS). We also keep a small herd of Highland cattle whose grazing, trampling and excrement play a significant role in improving the biodiversity of the ground while enriching our newly planted native forests. Over the last 15 years we have reduced deer numbers to around 6–7/km2, which is still above European norms where large carnivores exist. This action has already led to a significant increase in natural tree regeneration! In 2018 we stopped guest stalking with the aim of further reducing total deer numbers down to between 300 and 400 (3–4/km2).

Wild cat, Alladale.

AWR’s Highland Outdoor Wilderness Learning (HOWL) programme has been operational since 2008. Each year we host over 150 teenagers, from multiple regional schools and colleges, who come up for five days at a time to wild-camp and undertake a variety of nature-based activities. This transformational experience has led to two past attendees becoming AWR rangers!

Finally, guest numbers staying at one of Alladale’s four lodges has increased exponentially, which is a clear indicator that, with an environmental focus, it’s possible to attract more visitors and create greater job opportunities than would be the case operating an upland stalking estate. All in all a better plan, while also greatly enhancing the reserve’s biodiversity. That’s what I call a legacy.