Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «Ragged Rose»

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

The News Building

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Copyright © Dilly Court 2016

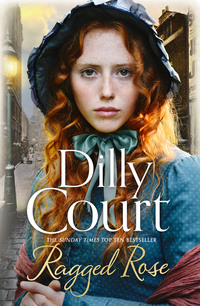

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

Cover photographs © Gordon Crabb (woman); City of London (background scene)

Dilly Court asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008137359

Ebook Edition © February 2016 ISBN: 9780008137366

Version: 2020-10-09

Dedication

For my great-niece, Evie Marian Jane Atchison.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

A Letter from Dilly

Read on for an exclusive extract from Dilly’s next festive novel

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Dilly Court

About the Publisher

Chapter One

Cupid’s Court, Barbican, London 1875

‘Do hurry up, Cora. We’re on in a minute.’ Rose edged past her sister, bending almost double to avoid knocking the sequin-encrusted gowns off the pegs in their tiny dressing room, which in reality was little more than a cupboard.

Cora patted a stray curl in place, making a moue as she studied her reflection in the fly-spotted mirror. The atmosphere was thick with the smell of burning lamp oil and greasepaint, with wafts of cigar smoke seeping under the door, and the ever-present odour of stale beer and spirits permeated every inch of the saloon. She stood up, smoothing the tight-fitting bodice of the daringly low-cut gown with a satisfied smile. ‘I’m ready.’

Rose opened the door in answer to an urgent knock.

‘On stage, girls.’ Tommy Tinker, the boy who undertook all the odd jobs that no one else wanted to do, stuck his head into the room, eyeing the girls with a cheeky grin. ‘Very nice too, if I might be so bold.’

‘Little boys should be seen and not heard,’ Cora said with a haughty toss of her head as she squeezed past him.

‘Show a bit of respect for your elders, young Tinker.’ Rose paused in the doorway, fixing him with a stony stare until he blushed and dropped his gaze.

‘Sorry, Miss Sunshine,’ he muttered, making way for her by flattening himself against the whitewashed wall of what had once been a coal cellar. This small space now served as general store, as well as dressing rooms for the acts who performed in Fancello’s Saloon.

‘It’s Miss Perkins,’ Rose said mildly. ‘Sunshine is our stage name, Tinker.’

He frowned. ‘Best hurry, miss. The patrons are getting restless.’

Rose bundled up her full skirt as she negotiated the steep, narrow staircase, taking care to keep the satin from brushing against the damp walls. With Cora following close behind she arrived in the wings just in time to hear Fancello’s introduction.

‘Ladies and gentlemen.’ He raised his voice in order to make himself heard above the general hubbub in the bar room. ‘I am proud to present for your delectation … the delicious and delightful Sunshine Sisters.’ He clapped enthusiastically and his brother, Alphonso, downed the last of his pint and thundered out the intro on the piano.

Ignoring the continuous chatter, the occasional bursts of raucous laughter, and with the odd salacious remark tossed in for good measure by someone the worse for drink, Rose and Cora performed ‘Pretty Little Polly Perkins of Paddington Green’ with appropriate actions, and then launched into their dance routine. This had the effect of largely silencing the rowdy element of their audience, as the men craned their necks in order to get a better view of ladies’ legs, and the occasional glimpse of a garter.

Rose and Cora left the small stage to a tumult of applause, and were called back for an encore, but Fancello intervened.

‘You have had sunshine brought into your lives, gentlemen. The young ladies must not be allowed to exhaust themselves, but they will perform again later in the evening.’ He joined the sisters in the wings. ‘Well done,’ he said, twirling his waxed moustache, a nervous habit that Rose had noted several times in the past. ‘We mustn’t spoil them – always leave the punters longing for more.’

‘Yes, Signor Fancello,’ Cora said with a coy smile. ‘You’re always right.’

Rose eyed him suspiciously. ‘We agreed one performance a night, signor. You just said we would be on again later – I take it that we’ll be paid double?’

He released his moustache and it recoiled like a watch spring. ‘I’m paying you for a night’s work, Miss Sunshine. Don’t bring on the storm clouds. Fancello is a fair man, but you can be replaced.’

Cora laid a small hand on his arm, her large blue eyes misted with tears. ‘Don’t be cross, signor. We understand, don’t we, Rose?’

Rose ignored the warning look that Cora sent her. ‘We might not be as well-known as your bambina, but we have been popular amongst your clients, signor. I think we deserve to be paid accordingly.’

For a moment she thought that she had gone too far. Fancello’s dark curly hair seemed to stand on end like the fur of an outraged feline, and his full lips quivered, but a sly smile spread across his face and he roared with laughter. ‘You drive a hard bargain, Miss Sunshine. I will pay you extra if you perform again later. My little bambina has the voice of an angel, but she is delicate like her mamma and we are careful to protect her.’ He cocked his head on one side, frowning at the sound of a slow hand clap from the saloon. ‘Go out there and circulate, but don’t allow the punters to get too familiar.’ He cupped his hand round his lips. ‘Tinker.’

Popping up like a jack-in-the-box, Tinker appeared at his side. ‘Yes, guv?’

‘Where is the bambina? Why is she not ready to go on stage?’

Tinker shook his head. ‘Your lady wife says it’s no go, guv. The little ’un ain’t to appear on stage as she’s took sick.’

‘We’ll see about that.’ Fancello strode off towards the staircase.

‘Is she ill?’ Cora asked anxiously. ‘It’s not catching, is it? I was talking to her earlier and she seemed perfectly fine then.’

‘Gin,’ Tinker said, tapping the side of his nose. ‘The bambina likes a drop of gin and water to give her Dutch courage.’

Rose pursed her lips. She was no prude but she had listened to enough of her father’s sermons to know the difference between right and wrong. ‘She’s just a child, a defenceless little girl. She should be drinking warm milk with a little honey to help her voice.’

‘Ain’t you never had a close look at her?’ Tinker said with a superior smile. ‘Ain’t you never smelled the gin fumes on her breath, nor the tobacco smoke what clings to her hair and clothes?’

Cora’s eyes widened. ‘What are you saying, Tinker? Is this one of your jokes?’

‘I been with the Fancellos since they plucked me from the poorhouse, miss. I seen the way they encouraged little Clementia to smoke and drink. It means she don’t eat much and she don’t grow proper – like us kids from the backstreets. Why do you think me legs is bowed and me arms don’t straighten out proper? Most of us kids suffered from rickets.’

Rose laid her hand on his bony arm. ‘It’s a terrible affliction, Tinker. I’m ashamed to think I didn’t notice your infirmities before, and I’m equally shocked to learn the truth about little Clemmie.’

‘Never mind her,’ Cora said urgently. ‘There’ll be a riot out there if we don’t put in an appearance. Besides which, I saw a really handsome young man seated at one of the tables. I’d swear that he had eyes for me and me alone.’

‘Best do it, miss.’ Tinker peered out through a gap in the curtains. ‘The signora is coming this way. She’s got that look about her like when she starts throwing things. I’m off.’ He turned and raced off towards the stairs that led up to the Fancellos’ private apartment.

Rose went to meet Signora Fancello, who did not look amused. ‘Your husband has asked us to do another performance this evening,’ she said boldly. ‘We have agreed but we must be out of the saloon before ten o’clock.’

Graziella Fancello’s winged eyebrows drew together in an ominous frown. ‘You are in no position to make demands on us, Miss Sunshine. We pay you to perform, and perform you will, even if we ask you to sing and dance at midnight.’

‘But, signora, our mama is unwell and we have to look after her. She will be worried if we’re out late. The streets of Islington are dangerous enough in daytime, let alone late at night, and we are two young women on our own.’

Graziella’s red lips hardened into a thin line. ‘I’ll think about it. Now go out there and socialise with the clients.’ She headed towards the stairs with a determined set of her chin.

‘Well done, Cora,’ Rose whispered, smiling. ‘You know how to handle the wretched woman.’

‘I suppose she’s gone upstairs to give poor Clemmie a piece of her mind.’ Cora adjusted her costume, pulling the bodice up in an attempt at a semblance of modesty. ‘We’d best go out and circulate. Who knows, I might catch the eye of a rich man and he’ll sweep me off my feet, and marry me?’

‘I’d settle for being spotted by the manager of the Pavilion Theatre or the Grecian. We could earn twice as much, and we wouldn’t have to pander to gentlemen with roving eyes and wandering hands.’ Rose braced her shoulders. ‘But we must leave here by ten, or Aunt Polly will have locked the doors.’

Cora pulled back the curtain and stepped down from the stage to a rousing cheer from the clientele: mostly well-dressed men of means who had come slumming. She headed for the blue-eyed gentleman she’d spotted earlier, who leaped to his feet with a courteous bow. Rose followed more slowly, walking between the tables, acknowledging the flattering comments, and ignoring suggestive remarks that would have made a courtesan blush. There were familiar faces amongst the audience, some whom she knew it was best to humour and then move on. Just as Fancello erupted onto the stage to introduce his bambina cara, Clementia, Rose came to a halt at a table occupied by a distinguished-looking gentleman of military bearing. He was older than the usual punter, and he had a kind, fatherly look about him.

‘You are on your own, sir,’ she said, smiling. ‘May I join you?’

He half rose from his chair, motioning her to take a seat. ‘That would be delightful, but you must excuse me if I don’t stand. I have a gammy leg – an old war wound, you understand.’

She sat down opposite him. ‘I’m sorry to hear that, sir. Were you in the Crimea?’

Just as he was about to reply, Clementia began to sing in a sweet clear soprano that momentarily stilled and silenced the audience. Rose sat back, watching the small creature perform. Poor Clemmie was never allowed out unaccompanied, Rose knew that for a fact. Tommy liked to gossip, and his favourite subject was little Clemmie, who was virtually a prisoner of love; doted on and fiercely protected by adoring parents. Rose was unsure whether this was entirely out of parental devotion, or whether Clemmie’s ma and pa had an eye to nurturing a valuable talent. Whatever the reason, the young girl had no life outside the walls of the smoky saloon.

Rose turned to the military gentleman with an encouraging smile. ‘You were about to tell me of your exploits, sir.’

‘Colonel Mountfitchet at your service,’ he said gallantly.

Rose felt herself blushing. ‘I’m Rose Sunshine. How do you do, Colonel?’

‘My friends call me Fitch.’

‘I – I couldn’t.’ Rose had a vision of her father’s shocked face were he to hear her being disrespectful to a much older gentleman, let alone a war hero. ‘That wouldn’t be proper, sir.’

‘I take it that Sunshine is not your real name, and I respect your right to anonymity.’ He leaned towards her. ‘What are you doing here, Rose? You’re not the sort of girl who normally frequents places such as this.’

‘My sister and I are here to entertain, sir. We don’t fraternise with the customers, if that’s what you are inferring.’

‘Certainly not, my dear, and it’s none of my business.’

Rose eyed him warily. This was not the usual way that conversations with patrons ran. There might be a little mild flirtation, but that was as far as it went. She had learned to slant her questions so that the gentlemen talked about their favourite topics, namely themselves, but the colonel was different. He seemed genuinely interested in her, and that was alarming.

He cleared his throat. ‘You must forgive me, Rose. It’s a long time since I was in the company of a beautiful young lady. I beg you to forgive an old soldier for his ill manners.’

‘No, sir. I won’t allow that,’ Rose said hastily. She leaned forward, lowering her voice. ‘My sister and I work of necessity, Colonel. We have our reasons, but I would ask you not to enquire further.’

He nodded and his pale grey eyes twinkled. ‘You have my word, Rose. Now will you allow me to buy you a drink? The signora has returned and she is looking this way. I imagine she expects to boost sales by sending the Sunshine Sisters behind enemy lines.’

Rose stifled a giggle. ‘I would hardly call you the enemy, Colonel, but I must warn you that she serves us lemonade and charges for champagne.’

‘I would expect nothing else from a businesswoman like the signora.’ He clicked his fingers to attract a waiter. ‘Champagne for the young lady,’ he said grandly. ‘And a whisky for me.’

A somewhat half-hearted round of applause heralded the end of Clemmie’s performance, and Rose was quick to note the frown on the signora’s face. Poor Clemmie would come in for some fierce criticism when her mother joined her upstairs. The colonel was clapping enthusiastically, but Rose had a feeling that he was acting from chivalry rather than appreciation of Clemmie’s pitch-perfect, but emotionless, render-ing of ‘Come into the Garden, Maud’. She nodded to the waiter, who placed a brimming glass on the table in front of her. ‘Thank you.’

He grinned and hurried away to serve a gentleman who was already the worse for wear. Rose sipped what indeed turned out to be lemonade. It had been a long day and she was tired, but it was not yet over.

The colonel added a dash of water to his whisky, and raised his glass to her. ‘Here’s to your lovely green eyes and russet hair, Miss Sunshine. May you continue to delight us for many an evening to come.’

‘Thank you, Colonel.’ Rose glanced over her shoulder and saw Cora beckoning to her. ‘I think we’re on again, so I must leave you.’ She downed the sweet drink in one. ‘I hope to see you here again, sir.’ He attempted to rise, but she held up her hand. ‘Please don’t get up, sir.’

He subsided onto his seat. ‘You’ve brought a little sunshine into an old man’s life, Rose. I will definitely patronise Fancello’s establishment again, and I will tell him so.’

Rose acknowledged his gallant remark with a smile before weaving her way through the closely packed tables to join her sister.

‘It’s nearly ten o’clock,’ Cora whispered. ‘We’d better go through this one double tempo.’ She climbed onto the stage and waved to Alphonso, who had a full pint glass in one hand and a cigar in the other. For a moment it looked as if he were about to ignore her signal, but Fancello had reappeared and he clapped his hands.

‘Ladies and gentlemen, I have pleasure to present, for a second time this evening, the superb, sweet and sensational Sunshine Sisters. Maestro, music, if you please.’ With an expansive flourish of his arms he turned to face the girls. ‘Smile.’

Alphonso rested his cigar on the top of the piano and took a swig of beer. With a rebellious scowl he flexed his fingers and began to play.

When they finally escaped from the stage, having taken several encores, Rose and Cora each did a quick change, crammed their bonnets on their elaborate coiffures and wrapped their shawls around their shoulders before leaving by the side door, which led into Cupid’s Court. It was dark and there were no streetlights to relieve the gloom of a March night. The buildings around them were mainly business premises, vacated when the day’s work came to an end. Their unlit windows stared blindly into the darkness, and homeless men and women huddled in doorways. The cobblestones were slippery beneath the girls’ feet and gutters overflowed with rain-water. They had missed a storm, but a spiteful wind tugged at their clothes and threatened to whip their bonnets off their heads as they ran towards the relative safety of Golden Lane. Gas lamps created pools of light, and, even though it was late, there were still plenty of people about, although it was a different crowd from the housewives, office workers, milliners and stay makers who frequented the busy thoroughfare in daylight. Darkness brought out the worst in society, and the girls held hands as they hurried on their way.

The home for fallen women was situated on the corner of Old Street and City Road, directly oppos-ite St Luke’s Hospital for Lunatics and the City of London Lying-In Hospital. The sour smell from the vinegar works behind St Mark’s church hung in a damp cloud, grazing the rooftops as it mingled with the fumes from the gas works in Pear Tree Street, and the odours belched out by the manufactories alongside the City Road Basin. Shrieks from the inmates of the asylum were indistinguishable from the screams of the women in labour in the building next door, and, in stark comparison, laughter and voices raised in drunken singing emanated from a nearby pub.

The door of the home opened just a crack in response to Rose’s rapping on the knocker.

‘Who is it?’ The young voice sounded wary.

‘It’s Rose and Cora,’ Rose said urgently. ‘Let us in, please, Sukey.’

‘You can’t be too careful,’ Sukey muttered as she let them into the dark hallway. ‘There’s one of them loonies escaped earlier today. We’ll all have our throats slit while we sleep in our beds.’ She closed the door and picked up an oil lamp.

Cora patted her on the shoulder. ‘I’m sure that the poor person will be far away from here by now.’

‘I imagine that the first thing people think about when they escape is to make their way home,’ Rose said in her most matter-of-fact voice. ‘So you need not be afraid.’

Sukey slanted her a sideways look. ‘Yes, miss. I expects you’re right.’ She drew herself up to her full height, although her twisted spine gave her the look of a young sapling stunted in its growth. ‘Shall I tell Miss Polly that you’re here? Only she’s up in the dormitory sorting out a fight.’

‘It’s all right,’ Cora said hastily. ‘We’ll go to the parlour.’

‘We can’t stay long,’ Rose added. ‘We’re late as it is.’

‘Your duds are laid out for you. I done it meself, so I know it’s done proper. You can’t trust the ser-vants to keep their traps shut or do things right.’

Rose kept a straight face with difficulty. ‘We appreciate everything you do for us, Sukey. If you’d be kind enough to tell Miss Polly that we’re here when she’s free, that would be splendid.’

Sukey puffed out her concave chest. ‘You can trust me, Miss Rose.’ She scuttled off with her lop-sided gait.

‘Poor thing,’ Cora sighed. ‘She’d be pretty if she didn’t have such a terrible disability.’

Rose headed for the parlour. ‘She copes very well, and she’s lucky that she’s got a good home here with Polly. She might have ended up in a circus or a freak show, poor soul.’ She paused to glance at the steep flight of stairs, listening to the shouts and streams of invective that flowed with such fluency. ‘I wonder if we ought to go upstairs and help.’

‘I don’t think so.’ Cora hurried on ahead of her. ‘I think Aunt Polly can handle the situation.’ She opened the parlour door and went inside.

The warmth from the coal fire enveloped Rose like a comforting blanket as she followed her sister into Polly’s inner sanctum, where nothing ever changed. Polly’s theatrical past was evoked by the play bills that covered the walls, and framed photographs of her in her heyday hung from the picture rail. Mementoes of her brief reign as queen of the London stage covered the entire surface of a large mahogany chiffonier, and sheet music of her most popular songs lay on the piano stool. One of her stage costumes was draped over a tailor’s dummy, standing proud between the two windows. It was faded, and moths had been feasting on the material, but Polly refused to pack it away. She clung to her memories, insisting that one day a theatre manager would come calling, and her star would shine again.

It was not an elegant room, but Rose had always felt more at home here than in the neat parlour at the vicarage, where the atmosphere was so often uncomfortable. It was Aunt Polly who had looked after the infant Rose and Cora when their mother was suffering from frequent bouts of illness. It was in this room that Polly had given the girls singing lessons and taught them dance routines, unbeknown to their strict father. It was to Aunt Polly they had come recently when news of their brother’s troubles reached them in a letter that Billy had sent from Bodmin Gaol. It was Polly who had given the girls the courage to go out and earn money to pay for his defence lawyer, and now Polly was helping them to keep their mission secret.

Rose was overtaken by a sudden wave of nostalgia as she breathed in the lingering aroma of Aunt Polly’s perfume, laced with the fumes of gin and overtones of brandy. She looked round the room with a feeling of deep affection. It was true that the furniture had been purchased in sale rooms and was well worn, but Polly said that gave each item a mystique and a history that was sadly lacking in anything brand-new. Polly’s favourite piece was a chaise longue, which was draped with exotic shawls, although the only occupant at this moment was a fat tabby cat of uncertain nature. He had wandered in from the street one night and taken up residence, bringing with him his feral dislike of all humans with the exception of Polly, whom he tolerated.

Cora was about to sit down when she spotted Spartacus, as Polly had named the animal, and she moved to a chair by the fire. The cat opened one eye, stretched and exposed his sharp claws, and then went back to sleep.

Rose began to undress. ‘Don’t get comfortable, Cora. We’ve got to get home before Pa sends out a search party. I can’t face an angry scene this evening.’

‘I’m tired,’ Cora complained bitterly. ‘My feet are sore and I don’t think I can walk another step.’

‘We can’t afford a cab. You’ll have to make the effort.’ Rose slipped off her blouse, sniffed it and shook her head. ‘It reeks of tobacco smoke and stale beer,’ she said, sighing. ‘I wouldn’t bother to change, but Ma would be sure to notice and demand an explanation.’

‘Couldn’t we say that the women here smoke and drink?’ Cora asked, smothering a yawn. ‘Aunt Polly would back us up. I know she would.’

‘Ma might be taken in, but Pa would know we were telling fibs. He has an uncanny ability to sniff out a lie. Neither you nor I have ever been able to look him in the face and fib.’

‘That’s not quite true,’ Cora insisted. ‘They think we spend our spare time helping the fallen women. Both Ma and Pa would have a fit if they knew what we were really doing. Especially Pa.’

‘And they mustn’t be allowed to find out,’ Rose said firmly. She picked up a grey linsey-woolsey gown and tossed it to her sister. ‘Come on, Corrie. Be a good girl and get changed. You know we’re doing this for a good cause.’

Cora raised herself to her feet and began undoing the buttons on her cotton blouse. ‘I know we’re doing it for Billy, but I wish he were here now.’ Her bottom lip trembled, but she sniffed and attempted a smile. ‘I miss him, Rosie. He’s the best brother a girl could have and I’ll never believe ill of him.’

‘Cora!’ Polly erupted into the room. ‘I’ve told you before not to mention William’s name in this house. You never know who might be listening.’

‘I – I’m sorry,’ Cora said, hanging her head. ‘But I do miss him and I want him to come home.’

‘That’s why we’re doing this.’ Rose slipped her gown over her head. ‘It will be worth it in the end, and who knows, we might become famous along the way.’ She turned to her aunt with a pleading look. ‘Don’t be cross with Cora, Aunt Polly. She’s tired and her feet hurt. We had to do two shows tonight.’

Polly threw herself down on the chaise longue, pushing the cat out of the way, to his obvious annoyance. Spartacus hissed and took a half-hearted swipe at her before settling down again on one of the velvet cushions. ‘Wretched animal,’ Polly said crossly. ‘I ought to throw you out on the street where you belong.’ She glanced up at Rose, who was eyeing her with a wry smile. ‘He’s useful. He keeps the rodent population under control.’ She leaned against the buttoned back rest. ‘Pour me a glass of gin, Cora. I’ve just had a tussle with two women who would like to slit each other’s throats.’

‘I’ll do it,’ Rose said, moving to the side table where Polly kept a selection of decanters. ‘You would think that they would support each other instead of falling out. They’ve all been abandoned by their husbands, and face the prospect of bringing up their children on their own. From what I’ve seen of the gentlemen who frequent the saloon, being married doesn’t stop a man having a roving eye.’

‘It’s true that most of my women have wedding rings.’ Polly stretched out her hand to take the drink from Rose. ‘But knowing those two upstairs, they’ve probably filched them from corpses.’

‘Why were they fighting?’ Cora asked.

Polly swallowed a mouthful of neat gin. ‘They’ve only just realised that they’ve been taken in by the same man, and he’s turned his back on both of them. They were at each other’s throats. I think they would have killed each other had they had a weapon other than a hairpin and a teaspoon. I must tell Ethel to lock away the kitchen knives tonight.’

Rose picked up the much-darned woollen shawl that she had worn when she left home earlier that evening and wrapped it around her shoulders. ‘Hurry up, Corrie. The sooner we set out the sooner you’ll be tucked up in your bed at home.’

‘I wish there was some other way for you girls to raise money,’ Polly said, frowning. ‘Heaven knows what your father would say if he knew about all this, and Eleanor would never let me hear the last of it. She was always the bossy older sister … in the old days, anyway.’

‘I’m sure she will understand when Billy tells her the whole story.’ Cora picked up her bonnet and rammed it on her head.

Polly’s rouged lips curved in a wry smile. ‘I don’t know about that, Cora. Eleanor thinks the sun rises and sets in her first-born, and your father is convinced that William is following in his footsteps. How could you tell a man of the cloth that his precious son is in gaol, awaiting trial for killing his best friend? Especially when we’ve all kept up the fiction that Billy is a guest of the Tressidick family in Cornwall.’

‘They must never know,’ Rose said firmly. ‘We won’t allow their hearts to be broken. Come on, Cora Perkins. It’s time we were home.’

It was less than a mile from the home for fallen women to St Matthew’s church, and the walk was uneventful, notwithstanding a bunch of drunken youths who staggered out of The Eagle tavern on the corner of City Road and Shepherdess Walk. Rose grabbed Cora by the hand and marched past with her nose in the air, which seemed to work as the young men made no attempt to molest them, resorting instead to hurling insults and collapsing with drunken laughter. Rose came to a halt on the bridge over the City Road Basin, where the Regent’s Canal came to a sudden end. A young woman was standing on the parapet and seemed about to throw herself into the murky waters, which were stained with indigo dye, coal dust and industrial effluent.