Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

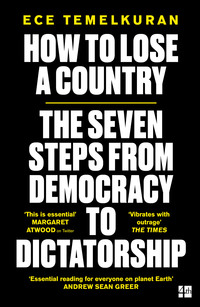

Loe raamatut: «How to Lose a Country»

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate 2019

Copyright © Ece Temelkuran 2019

Ece Temelkuran asserts her moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008294045

Ebook Edition © February 2019 ISBN: 9780008294021

Version: 2020-01-02

Dedication

For Umut.

His name means ‘hope’ in my mother tongue.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction: What Can I Do for You?

1 Create a Movement

2 Disrupt Rationale/Terrorise Language

3 Remove the Shame: Immorality is ‘Hot’ in the Post-Truth World

4 Dismantle Judicial and Political Mechanisms

5 Design Your Own Citizen

6 Let Them Laugh at the Horror

7 Build Your Own Country

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

What Can I Do for You?

The fighter jets are breaking the dark sky into giant geometric pieces as if the air were a solid object. It’s 15 July 2016; the night of the attempted coup in Turkey. I am piling pillows up against the trembling windows. I guess they’ve just dropped a bomb on the bridge, but I can’t see any fire. People are talking on social media about the bombardment of the Parliament Building. ‘Is this it?’ I ask myself. ‘Is tonight the Reichstag fire for what remains of Turkish democracy and my country?’

On TV, a few dozen soldiers are barricading the Bosporus bridge, shouting at the startled civilians: ‘Go home! This is a military takeover!’

Despite their huge guns, some of the soldiers are clearly terrified, and all of them look lost. The TV says it’s a military takeover, but this is not a coup as we know it. Coups usually wear a poker face – there’s no hustling or negotiating, and certainly no hesitation when it comes to using the heavy weaponry. The absurdity of the situation sees sarcasm kick in on social media. This kind of humour is not necessarily aiming for laughter; it’s more of a contest in bitter irony, which seems normal only to those engaged in it. The jokes mostly concern the idea that this is a staged act to legitimise the presidential system – rather than the parliamentary one – that President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has long been asking for, a change that would hand him even more power than he already has as the de facto sole ruler of the country.

The dark humour disappears as the skies over Istanbul and Ankara become busy hives of fighter jets. We are learning the language of war in real time. What I’d thought was a bomb was actually a sonic boom – the blast-like sound fighter jets make when they break the sound barrier. This is the proper terminology for the air breaking into giant pieces and raining down on us as fear: fear of realising that before the sun rises we might lose our country.

People in the capital city of Ankara are now trying to differentiate between sonic booms and the sound of real bombs hitting Parliament and the intelligence service headquarters. The catastrophe unfolding in front of our eyes is constantly blurred by the absurdity of the news reports on our screens. Live on air, MPs are running around Parliament trying to find the long-forgotten air-raid shelter, and when they finally do locate it, nobody can find the keys, while outside in the streets people dressed in their pyjamas are kicking tanks, cigarettes in their mouths, and shouting at the jets.

A communications explosion is occurring on our TV screens, and many of us know that this is very much not normal. Turkey’s recent history has taught us that a coup starts with the army taking politicians into custody and shutting down news sources. Also, coups tend to happen in the early hours of the morning, not during television prime time. In this meticulously televised coup, government representatives appear across TV channels all night long, calling on the people to take to the streets and oppose the army’s attempted takeover. The internet does not slow down in the way it usually does whenever something occurs to challenge the government; on the contrary, it’s faster than ever. Even so, the speed and intensity of the night’s events do not allow the sceptics to properly process these strange details.

Erdoğan communicates using FaceTime, with his messages broadcast on CNN Turk. He calls everyone out into the city centres. Like most people, I do not anticipate the government’s supporters taking to the streets to confront the military. Since the founding of the modern Turkish republic in 1923, under Kemal Atatürk, the army has traditionally been the most respected institution in the country, if not the most feared. But apparently much has changed since the last military coup in 1980, when it was the leftists who resisted and were imprisoned and tortured; the president’s call resonates with thousands.

In no time the TV screens are showing the young, terrified soldiers being beaten and strangled to death by this mob. And that is when the never-ending sela from all the minarets in the country begins. Sela is a special prayer recited after death. It has such a shivering tone that even those who are not familiar with Muslim customs can tell that it is about the irreversible, the end. Tonight, sela is followed by loud announcements from minarets calling people to the streets in the name of God, to save the president, the democracy, the nation … The tune of death now shares the sky with jets, the delirious ‘Allahu akbar’s of Erdoğan supporters and the soldiers’ cries for help. And I remember the poem that started everything: ‘The minarets are our bayonets/The domes our helmets/The mosques our barracks/And the faithful our soldiers.’ It was Erdoğan who recited the poem at a public event in 1999, leading to him being imprisoned for four months for ‘inciting religious hatred’, and transforming him first into a martyr for democracy, then a ruthless leader. And after seventeen years, on the night of the coup the poem sounds like a self-fulfilling prophecy, a promise that has been kept at the cost of a country.

We have learned over time that coups in Turkey end the same way regardless of who initiated them. It’s like the rueful quote from the former England footballer turned TV pundit Gary Lineker, that football is a simple game played for 120 minutes, and at the end the Germans win on penalties. In Turkey, coups are played out over forty-eight-hour curfews, and the leftists are locked up at the end. Then afterwards, of course, another generation of progressives is rooted out, leaving the country’s soul even more barren than it was before.

As I watch the pro-government news channels throughout the night it becomes clearer by the minute that it is business as usual. Pictures and videos come through of arrested soldiers lying naked in the streets under the boots of civilians – as leftists lay under army boots after the coup in 1980 – and the news channels and the government trolls on social media, not at all paralysed like the rest of us, present us with the perspective they deem most appropriate: ‘Thanks to Erdoğan’s call, the people saved our democracy.’

‘Allahu akbar’s multiply on my street, accompanied by machine-gun shots from the circulating cars. After so many years spent under AKP rule, devotion to the army has apparently been replaced by religious commitment to Erdoğan. We are watching his face and name become the emblems of the new Turkey we’ll wake up to. Beneath the madness and the noise a carefully crafted propaganda machine is fully operational, already preparing the new political realm that will come into being in the morning. And having long been a critic of Erdoğan’s regime, as dawn breaks it becomes Kristall-clear that there won’t be a place for people like me in this new democracy.

Watching a disaster occur has a sedating effect; like millions of people around the country, I am numb. As our sense of helplessness grows along with the calamity, the cacophony transforms into a single siren, a constant refrain: ‘There’s no longer anything you can do; this is the end.’ The global news channels jump in. For the rest of the world, the night’s events are like the opening scene of a political thriller, but in fact this is the climax, the dénouement. It has been a very long and exhausting film, unbearably painful viewing for those of us who were forced to watch or take part. And I remember how it began: with a populist coming to town. Which is why, as the British and American TV anchors put hasty questions to the studio analysts, I feel like saying, ‘As our story ends, yours is only just beginning.’ A bleak dawn breaks.

I remember the exact day I experienced dawn for the first time. I woke up early one morning to the sound of the radio playing loudly in the living room, and found my mother and father chain smoking as they listened to a coup being declared. Their faces darkened as the day broke. It was 12 September 1980, and I looked up at the clear blue sky and said to myself, ‘Oh, this must be what they call dawn.’ I was eight, and one of the most vicious military coups in modern history was just getting started. My mother was silently crying, as she was to do frequently for several years after that dawn.

From that day forth, like millions of other children with parents who wanted a fair, equal and free Turkey, I grew up on the defeated side; among those who always had to be careful and who were, as my mother told me whenever I did less than perfectly at school, ‘obliged to be smarter than those in power because we are up against them’. On the night of 15 July 2016 ‘we’, as ever, were smarter than ‘them’, as we combined penetrating analysis with brilliant sarcasm. But in every square of every city in the country, raging crowds were playing the endgame, perhaps not as smartly, yet with devastating effect.

On 15 July 2016, my nephew Max Ali was the same age I was on 12 September 1980. He is one and a half years older than his brother, Can Luka. They are half-Turkish, half-American, and they live in the US. They were supposed to have gone home to America on 16 July, after a vacation spent with their babaanne – ‘grandmother’ in Turkish – my mother. Max Ali is a religious devotee of babaanne breakfasts. He is one of the lucky few on the planet who know of epic Turkish breakfasts, and he believes only babaanne knows how to make them. As a family, we’re always proud that he chooses tomatoes and Turkish cheese over Cheerios, which my father calls ‘animal food’. Had they not experienced the dawn during the coup their memories of babaanne would have been limited to indulgent breakfasts. But instead of heading to the airport that morning, as day broke they watched their babaanne crying and chain smoking in front of the TV. My mother told me Max Ali asked the same question I’d asked thirty-six years before: ‘Did something bad happen to Turkey?’ Babaanne was too tired to tell him that every generation in this country has its own dark memory of a dawn. She gave the same answer she had given me thirty-six years previously: ‘It is complicated, my dear.’

How and why Turkish democracy was finally done away with by a ruthless populist and his growing band of supporters on the night of 15 July 2016 is a long and complicated story. The aim of this book is not to tell how we lost our democracy, but to attempt to draw lessons from the process, for the benefit of the rest of the world. Of course, every country has its own set of specific conditions, and some of them choose to believe that their mature democracy and strong state institutions will protect them from such ‘complications’. However, the striking similarities between what Turkey went through and what the Western world began to experience a short while later are too many to dismiss. There is something resembling a pattern to the political insanity that we choose to name ‘rising populism’, and that we are all experiencing to some extent. And although many of them cannot yet articulate it, a growing number of people in the West sense that they too may end up experiencing similar dark dawns.

‘Turks must be watching us and laughing their asses off tonight,’ read an American tweet on the night of Donald Trump’s election victory less than five months after the failed coup attempt. We weren’t. Well, maybe one or two smirks might have appeared. Behind those smirks, though, lay exasperation at having to watch the same soul-destroying movie all over again, and this time on the giant screen of US politics. We wore the same pained expression after Britain’s Brexit referendum, during the Dutch and German elections, and whenever a right-wing populist leader popped up somewhere in Europe sporting the movement’s signature sardonic, bumptious grin.

On the night of the US presidential election, on the day of the Brexit referendum result, or when some local populist fired up a surprisingly large crowd with a speech that sounded like total nonsense, many asked the same question in their different languages: ‘Is this my country? Are these my people?’ People in Turkey, after asking these questions for almost two decades and witnessing the gradual political and moral collapse of their homeland, regressed to another dangerous doubt: ‘Are human beings evil by nature?’ That question represents the final defeat of the human mind, and it takes a long and excruciating time to understand that it’s actually the wrong question. The aim of this book is to convince its readers to spare themselves the time and the torture by fast-forwarding the horror movie they have recently found themselves in, and showing them how to spot the recurring patterns of populism, so that maybe they can be better prepared for it than we were in Turkey.

It doesn’t matter if Trump or Erdoğan is brought down tomorrow, or if Nigel Farage had never become a leader of public opinion. The millions of people fired up by their message will still be there, and will still be ready to act upon the orders of a similar figure. And unfortunately, as we experienced in Turkey in a very destructive way, even if you are determined to stay away from the world of politics, the minions will find you, even in your own personal space, armed with their own set of values and ready to hunt down anybody who doesn’t resemble themselves. It is better to acknowledge – and sooner rather than later – that this is not merely something imposed on societies by their often absurd leaders, or limited to digital covert operations by the Kremlin; it also arises from the grassroots. The malady of our times won’t be restricted to the corridors of power in Washington or Westminster. The horrifying ethics that have risen to the upper echelons of politics will trickle down and multiply, come to your town and even penetrate your gated community. It’s a new zeitgeist in the making. This is a historic trend, and it is turning the banality of evil into the evil of banality. For though it appears in a different guise in every country, it is time to recognise that what is occurring affects us all.

‘So, what can we do for you?’

The woman in the audience brings her hands together compassionately as she asks me the question; her raised eyebrows are fixed in a delicate balance between pity and genuine concern. It is September 2016, only two months after the failed coup attempt, and I am at a London event for my book Turkey: The Insane and the Melancholy. Under the spotlight on the stage I pause for a second to unpack the invisible baggage of the question: the fact that she is seeing me as a needy victim; her confidence in her own country’s immunity from the political malaise that ruined mine; but most of all, even after the Brexit vote, her unshaken assumption that Britain is still in a position to help anyone. Her inability to acknowledge that we are all drowning in the same political insanity provokes me. I finally manage to calibrate this combination of thoughts into a not-so-intimidating response: ‘Well, now I feel like a baby panda waiting to be adopted via a website.’

This is a moment in time when many still believe that Donald Trump cannot be elected, some genuinely hope that the Brexit referendum won’t actually mean Britain leaving the European Union, and the majority of Europeans assume that the new leaders of hate are only a passing infatuation. So my bitter joke provokes not even a smile in the audience.

I have already crossed the Rubicon, so why not dig deeper? ‘Believe it or not, whatever happened to Turkey is coming towards you. This political insanity is a global phenomenon. So actually, what can I do for you?’

What I decided I could do was to draw together the political and social similarities in different countries to trace a common pattern of rising right-wing populism. In order to do this I have used stories, which I believe are not only the most powerful transmitters of human experience, but also natural penicillin for diseases of the human soul. I identified seven steps the populist leader takes to transform himself from a ridiculous figure to a seriously terrifying autocrat, while corrupting his country’s entire society to its bones. These steps are easy to follow for would-be dictators, and therefore equally easy to miss for those who would oppose them, unless we learn to read the warning signs. We cannot afford to lose time focusing on conditions unique to each of our countries; we need to recognise these steps when they are taken, define a common pattern, and find a way to break it – together. In order to do this, we’ll need to combine the experience of those countries that have already been subjected to this insanity with that of Western countries whose stamina has not yet been exhausted. Collaboration is urgently required, and this necessitates a global conversation. This book humbly aims to initiate one.

ONE

Create a Movement

‘We have to take the deer! We have to!’

So says four-year-old Leylosh, shouting to emphasise the fact that we simply must put the imaginary deer on the infinitely large back seat of our imaginary car, which is already filled by several other animals, including a dinosaur we luckily managed to rescue from freezing. We are driving from Lewisburg, a once-thriving small farming town, sixty miles north of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, to her granny’s house in Istanbul, to deliver the Lego duck that we built and then cooked on a miniature stove. Leylosh is squinting in the imaginary wind and providing a scary winter soundtrack for our arduous journey: ‘Oouuuuvvoouuuv!’ Now and then she checks with a quick side glance to make sure I’m fully engaged. Satisfied with my powers of imagination, she turns back to reassure our passengers: ‘Don’t be afraid. We’ll be at Granny’s soon. We don’t have to go to school today.’

In a less exciting parallel universe, she will have to go to kindergarten in fifteen minutes, and in an hour’s time I’ll have to give a lecture at Bucknell University, a liberal arts college, on ‘rising populism’ and my novel The Time of Mute Swans, which partly deals with how Turkey became the perfect case study for the topic. Leylosh’s mother Sezi, a long-time friend who teaches at Bucknell, talked me into this, because she believes that American academia needs to hear about the Turkish experience and to be warned about the later stages of the Trump administration. It is therefore now time to stop teaching Leylosh how to ‘kiss like a fish’ and return to my real-life role: floating like the angel with a bugle in Bruegel’s The Fall of the Rebel Angels to alarm the wool-gathering masses. Sezi keeps checking her watch. But neither Leylosh nor I are keen to get out of the imaginary car, and in a way, her reasons are no less political than mine.

Sezi is a fortepianist and an expert on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century musical instruments. Leylosh probably thinks all mothers play Chopin on antique pianos to persuade their daughters to eat their breakfast. It’s doubtless no more unusual to her that her father is an anthropologist who periodically visits indigenous tribes in the Amazon rainforest. Her school, a kindergarten for children whose parents work at the university, a safe haven for children of cosmopolitan academics in a small American town, is full of kids like her; they speak at least two languages, travel regularly between continents, and are blissfully unaware that what’s normal to them is far from ordinary.

‘She used to love going to school,’ says Sezi. But lately the mornings have begun resounding with cries of ‘No, Mom! No!’ As Leylosh holds on to the door of our imaginary car, refusing to leave for school, her mother explains that this new attitude, like many other inconveniences in the US, began after Trump came to power. Herein lie the political troubles of the four-year-old Leylosh.

The morning after the election, Leylosh arrived at school with her mother. The three teachers were waiting at the door, hands on their hips and brandishing new sardonic smiles. ‘It was as if they were telling us to “suck it up”!’ says Sezi. ‘They’re all Trump supporters who are taking care of the children of Bernie or Hillary voters. The tension has been gradually mounting ever since, and it now affects the children.’ Sezi stops to find the right words: ‘These people, they changed all of a sudden, it’s as if they are now a different species.’

As the Argentinian proverb goes, ‘A small town is a vast hell.’ This is especially the case in today’s world, because the phenomenon of rising populism has a lot to do with the provinces. Small towns are often where people first encounter this social and political current. However, they wouldn’t describe it as diligently as the political analysts – and even if they did, their concerns would go largely unheard. The mobilising narrative of the new political direction feeds on provincial perceptions of life and the world, perceptions that are seen as too archaic to be understood by cosmopolitans. The small, unsettling changes in the provinces can seem inconsequential in big cities, where monitoring one’s neighbours is a lost habit. It is therefore only long after right-wing populism has been felt by those in the provinces that it is diagnosed by the political analysts and big media.

Sezi gives me more examples of how people’s general attitudes towards one another in her small town changed after Trump’s victory, examples that might sound insignificant to big-city folk: ostentatiously smirking when the liberal academics enter local restaurants, or not removing ‘Make America Great Again’ signs from front gardens months after the election, and so on. As the examples multiply, it’s as if she’s trying to describe a strange smell: ‘It’s like it was already there, boiling away silently, and Trump’s victory activated something, some dark motion was unleashed.’

Something has indeed been unleashed around the Western world. In several countries an invisible, odourless gas is travelling from the provinces to the big cities: a gas formed of grudges. A scent of an ending is drifting through the air. The word is spreading. Real people are moving from small towns towards the big cities to finally have the chance to be the captains of their souls. Nothing will stay unchanged, they say. A new we is emerging. A we that probably does not include you, the worried reader of this book. And I remember how that sudden exclusion once felt.

‘No, we are different. We are not a party, we’re a movement.’

It is autumn 2002, and a brand-new party called the Justice and Development Party, AKP, with a ridiculous lightbulb for an emblem, is participating in a Turkish general election for the first time. Being a political columnist, I travel around the country, stopping off in remote cities and small towns, to take the nation’s pulse before polling day. As I sit with representatives of other, conventional parties in a coffee shop in a small town in central Anatolia, three men stand outside the circle, their eyebrows raised with an air of lofty impatience, waiting for me to finish my interview. I invite them to join us at the table, but they politely refuse, as if I am sitting in the middle of an invisible swamp they don’t want to dirty themselves in. When the others eventually prepare to leave, they approach me as elegantly as macho Anatolians can. ‘You may call us a movement, the movement of the virtuous,’ the man says. ‘We are more than a party. We will change everything in this corrupt system.’ He is ostentatiously proud, and rarely grants me eye contact.

The other two men nod approvingly as their extremely composed spokesman fires off phrases like ‘dysfunctional system’, ‘new representatives of the people, not tainted by politics’, ‘a new Turkey with dignity’. Their unshakeable confidence, stemming from vague yet strongly held convictions, reminds me of the young revolutionary leftists I’ve written about for a number of years in several countries. They give off powerful, mystic vibes, stirring the atmosphere in the coffee shop of this desperate small town. They are like visiting disciples from a higher moral plane, their chins raised like young Red Guards in Maoist propaganda posters. When the other small-town politicians mock their insistence on the distinction between their ‘movement’ and other parties, the three men appear to gain in stature from the condescending remarks, like members of a religious cult who embrace humiliation to tighten the bonds of their inner circle.

Their spokesman taps his fist gently, but sternly, on the table to finish his speech: ‘We are the people of Turkey. And when I say people, I mean real people.’

This is the first time I hear the term ‘real people’ used in this sense. The other politicians, from both left and right, are annoyed by the phrase, and protest mockingly: ‘What’s that supposed to mean? We’re the real people of Turkey too.’ But it’s too late; the three men delight in being the original owners of the claim. It is theirs now.

After seeing the same scene repeat itself with little variation in several other towns, I write in my column: ‘They will win.’ I am teased by my colleagues, but in November 2002 the silly lightbulb party of the three men in the coffee shop becomes the new government of Turkey. The movement that gathered power in small towns all over the country has now ruled Turkey uninterrupted for seventeen years, changing everything, just as they promised.

‘We have the same thing here. Exactly the same thing! But who are these real people?’

It’s now May 2017, and I am first in London, then Warsaw, talking about Turkey: The Insane and the Melancholy, telling different audiences the story of how real people took over my country politically and socially, strangling all the others who they deemed unreal. People nod with concern, and every question-and-answer session starts with the same question: ‘Where the hell did these real people come from?’

They recognise the lexicon, because the politicised and mobilised provincial grudge has announced its grand entrance onto the global stage with essentially the same statement in several countries: ‘This is a movement, a new movement of real people beyond and above all political factions.’ And now many want to know who these real people are, and why this movement has invaded the high table of politics. They speak of it as of a natural disaster, predictable only after it unexpectedly takes place. I am reminded of those who, each summer, are surprised by the heatwave in Scandinavia, and only then recall the climate-change news they read the previous winter. I tell them this ‘new’ phenomenon has been with us, boiling away, for quite some time.

In July 2017, a massive iceberg broke off from Antarctica. For several days the news channels showed the snow-white monster floating idly along. It was the majestic flagship of our age, whispering from screens around the world in creaking ice language: ‘This is the final phase of the age of disintegration. Everything that stands firm will break off, everything will fall to pieces.’ It wasn’t a spectre but a solid monster telling the story of our times: that from the largest to the smallest entity on planet earth, nothing will remain as we knew it. The United Nations, that huge, impotent body created to foster global peace, is crumbling, while the smallest unit, the soul, is decomposing as it has never been before. A single second can be divided up into centuries during which the wealthy few prepare uncontaminated living spaces in which to live longer while tens of thousands of children in Yemen die of cholera, a pre-twentieth-century disease. The iceberg was silently screaming, The centre cannot hold.

Tasuta katkend on lõppenud.