Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «Sacred and Profane»

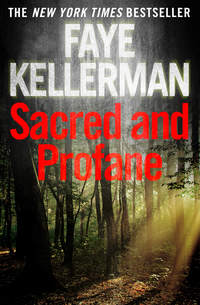

FAYE KELLERMAN

SACRED AND PROFANE

A PETER DECKER AND RINA LAZARUS NOVEL

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publisher 2014

Copyright © Faye Kellerman 1987

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com

Faye Kellerman asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © January 2014 ISBN: 9780007536382

Version: 2016-03-24

Dedication

For my rocks of ages, past and present:

My father, Oscar, alav hashalom.

I miss you very much.

My mother, Anne.

My ingenious one and only, Jonathan.

And the three musketeers,

Jesse, Rachel, and Ilana.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Faye Kellerman

Predator

About the Publisher

1

You can keep your white Christmas, thought Decker dreamily, as sunlight blanketed his prone frame. Give me December in L.A. anytime. Currier and Ives snowscapes looked swell on wrapping paper, but as far as he was concerned, icy Christmas winters were best left to penguins and polar bears.

Besides, he wasn’t really sure what relevance Christmas—with or without snow—held for him any more. No tree adorned the picture window of his living room, no cards sat atop the mantle of the fireplace, no multicolored lights hung along the wood planked siding of his ranch. Hell, here it was the day of Christmas Eve and he was out camping in the foothills, isolated from civilization, playing big brother to two little boys with yarmulkes. Christmas had never been a big deal to him, but still it felt strange. Some habits were hard to shake.

Using his knapsack for a pillow, he shifted onto his back. The air was sweet and tangy, the ground rich with mulch. Throwing an arm over his eyes, he noticed that it had been cooked a deep salmon and he cursed his coloring, typical for a redhead—all burn, no tan. He should have been more generous with the sunscreen. The arm, already dully throbbing, would blossom into full-fledged pain by tonight. He propped himself onto his elbows and called out to Ginger. The Irish setter trotted over to him, plopped down by his side, and went to sleep.

Decker glanced at Sammy, who sat twenty feet away, reading while dipping his toes into an isolated pool of rainwater. Behind him, a narrow stream carried mountain run-off from last week’s rains. Earlier in the day, Decker had offered to take the boys wading, but Sammy had complained that the water was too cold. Though he wasn’t weak or timid, he just wasn’t keen on the outdoors. The star-studded nighttime sky, the hikes, the cookouts had left him unmoved. Though he insisted he was having the time of his life, Decker knew the kid would have been just as happy holed up anywhere as long as he had Decker’s undivided attention. The boy could talk. Often, after his younger brother, Jacob, had fallen asleep, Sammy would start to pour his heart out, engaging Decker in conversation that sometimes lasted until the early hours of the morning. He was an overly mature kid, not surprising for the first born who’d taken on the role of man of the house.

Jacob was a different story. The eternal optimist, an enthusiastic youngster who could elicit a smile from a slab of marble. Great at amusing himself. Right now he was busy watching an ant hill, eyes glued to the nonstop action.

Decker enjoyed both of the boys, but knew if he walked out of their lives tomorrow, Jake would recover quickly. Sammy was the vulnerable one. And that worried him because his relationship with their mother was so ambiguous. He and Rina were in love but not yet lovers. Her religious values forbade intimacy outside of marriage, and marriage right now was impossible. They were in limbo until Decker officially converted.

There was an easy way out. He could reveal to Rina that he was adopted and that his biological parents were Jewish, so there was no legal reason for him to convert. But he didn’t consider that a viable option. Too dishonest. He was a product of his real parents—the man and woman who’d nurtured him. And they had raised him a Baptist. Besides, Rina deserved a genuinely committed Jew for a husband, not a Jew by accident of birth. Anything less would make her miserable. He knew he’d have to come to Orthodoxy on his own.

He inhaled deeply, filling his lungs with the pungent, crisp air.

He was making progress. His weekly sessions with Rabbi Schulman had shown him to be a quick learner. So far, he had no trouble grasping the intellectual and legal aspects of Judaism. But Hebrew remained a roadblock. The boys loved to play teacher with him, drilling him on the alef beis from their first grade primers, correcting his pronunciation and handwriting. They giggled when he made a mistake and flooded him with compliments when he came up with a correct answer. It was a game with them, an ego boost to instruct a grown-up, and though he went along with their lessons good-naturedly, inside, in spite of himself, he was humiliated. Afterwards, he’d return home and take out his feeling of frustration on his horses, running them around his acreage, working up a sweat until he smelled like a man and no longer felt like a child.

He lay back down and groaned. You’re on vacation, he admonished himself. Take it easy and forget your obligations. He had no trouble blanking out work, but as always, his cloudy status with Rina—and Judaism—continued to gnaw at him. Seeing life through the skewed eye of a cop, Decker found faith hard to come by.

The sun grew stronger and he took refuge under a Douglas fir. He closed his eyes and tried to concentrate on pleasant images: his daughter Cindy as a little girl, laughing carelessly as she pumped her legs to swing, himself as a boy, ’gator baiting with friends in the Everglades, Rina’s touch, her breath … breath lids grew heavy. Halfway through a jumbled dream, he felt rain on his trousers. Startled, he sat up, only to see Jacob standing over him, gleefully sprinkling his legs with dirt.

“What’s that for?” he asked, wiping off his clothes.

The boy shrugged.

“You bored?”

“A little.”

“Hungry?”

“A little.”

Decker tousled the ebony hair that stuck out from under Jacob’s kipah and unzipped the knapsack.

“We’ve got peanut butter or salami sandwiches,” he announced.

“What about the chicken?”

“Finished it yesterday.”

“The bagels?”

“They’re gone, too. We’re on our last day of vacation, Kiddo. The way we’ve been packing it away, it’s a wonder we haven’t run out of food altogether.”

“I’ll take peanut butter.”

“Where’s your brother?”

“I dunno.”

Decker stood up and looked around. Ginger rose with him, coppery fur gleaming in the sunlight. Sammy was nowhere in sight.

“Wasn’t he just reading over there?” Decker asked.

“He said he was going for a walk,” Jake answered. “You were sleeping. He told me not to bother you, but I got bored.”

“Sammy?” Decker called out, taking a few steps.

Nothing.

“When did he leave?”

“I dunno.”

Decker cupped his hands and called out:

“Sammy Lazarus, are you playing a game with me?”

He waited for a response. The sounds of the woods became magnified: bird songs, the rush of water, the buzz of insects.

“Hmm. Must have wandered off.” Decker took Jake’s hand and started to check out the immediate area. The dog followed.

“Sammy?”

Silence.

“Sammy, can you hear me?” Decker frowned and patted the dog. “Know where Sammy is, Ginger?”

The dog’s ears perked up, but her expression was blank.

“Sammy!” Jake called out.

“Okay,” Decker thought out loud. “Let’s take this one step at a time. He can’t be very far away.”

He picked up Sammy’s discarded sweat jacket and held it under the dog’s nose. She immediately skipped over to the area where Sammy had been sitting and parked herself.

The ground revealed a few bare footprints. Decker tried to follow them, but they were light and sporadic, disappearing altogether as the copse thickened with foliage.

“Sammy?” Decker bellowed.

Stay organized. He constructed an imaginary hundred-foot radius from the last footprint and decided to search that area meticulously, go over every single inch for a sign of a footprint, a torn piece of clothing …

Ten minutes of hunting and shouting proved to be fruitless.

“Where is he?” Jake asked nervously.

“He’s somewhere around here,” Decker said. Despite his anxiety, he kept his voice steady. “We’ll find him, Jakey. Don’t worry …. Sammy!”

“Why doesn’t he answer?”

“You know your brother. His head’s in the clouds.”

Decker was not given to panic—his job required a detached mind and a cool head—but images began to form in his mind. Horrible images …

“Sammy!” he shouted.

“Maybe he hurt himself,” Jacob said. His bottom lip quivered.

“I’m sure he’s fine, Kiddo,” Decker answered.

But the grotesque images grew more vivid. The look of terror on Rina’s face—he’d seen her like that before …

“Sammy, can you hear me!” he yelled.

“Sammy!” Jake echoed, then turned to Decker, wild-eyed. “Peter, what are we gonna do?”

“We’re going to find your brother, that’s what we’re going to do.” Kids, he thought. You need eyes in the back of your head. “Sammy!”

“Peter, I’m scared.”

“It’s going to be fine, Jakey,” Decker said.

His responsibility. His fault.

“Did you see or hear anything unusual while I was sleeping?” he asked Jake.

The boy shook his head fiercely.

“Then he’s got to be around somewhere. He’s just lost.” As opposed to kidnapped. “Sammy!”

His voice was growing hoarse.

All those kids. Those missing kids. He knew it all too well. Goddam dumb parents, he used to think. Yeah, they were goddam dumb. He was goddam dumb, too. Suddenly enraged, he ripped through the area like a wounded animal, trying to clear a path for himself and Jacob.

The little boy started to cry. Decker picked him up, hugged him, and continued the search as Jake clung tightly to his neck.

“Maybe we should head back, Peter,” Jake suggested, sniffing. “Maybe Sammy went back to where we were.”

Decker knew otherwise. Sammy should have been able to hear their calls even if he were back at the campsite.

“Sammy?” he tried once more.

He needed help, the sooner the better. Lots of people … Helicopters … There was still plenty of daylight left, but no time to waste. He gave the empty woods a final once over and headed back toward camp.

Suddenly, Ginger took off, her haunches leaping forward in a single fluid motion. The two of them raced after her and saw a small figure, shrouded by trees, standing over a thick clump of underbrush.

Decker ran over to the shadow and grabbed it firmly by the shoulders.

“Damn it, Sammy!” he said. “Didn’t you hear me calling you? You scared me half to death!” He clutched him to his chest. “Why didn’t you answer me?”

The boy held himself rigid. Decker saw that his eyes were glazed.

“What’s wrong with you? What happened?”

“Yuck!” Jake spat out, staring into a pile of decayed foliage. Decker looked down.

There were two charred skeletons. Except for the right shinbone, which was buried under leaves and dirt, the first skeleton was completely exposed, a blackened arm-bone and fist sticking straight up as if beckoning for a hand to hoist it to its feet. The skull and the breastbone bore holes the size of a silver dollar. Shreds of flesh were clinging to the torso, petrified and discolored from exposure.

The second skeleton was partially buried, the ribcage and left legbone completely covered with dirt. A trail of leaves overflowed from the lower jaw, falling downward as if the dead mouth were vomiting detritus. Bits and pieces of charred skin stuck to the pelvis and limb bones, but unlike the first skeleton, the eye sockets and cracked skull retained dew-laden globs of jelly that glistened in the sunlight. Brain and eye. A cloud of flies and a mass of black beetles were feasting on the leftover morsels, unperturbed by the presence of intruders.

Gently, Decker walked the boys away from the ghastly sight and swore to himself. Nothing like a vacation to remind him of work.

“Are they real, Peter?” Sammy asked at last, his troubled eyes beseeching Decker.

“Yes, they’re real.”

“What are we gonna do?” Jake asked.

“I think we should bentch gomel,” Sammy said quietly.

“What’s that?” Decker asked.

“It’s like what you say when you don’t get killed in a car crash, or like when you don’t die from the chicken pox.” Jacob looked up at Decker. “I don’t feel so good.”

“Sit down, Jakey. Catch your breath.”

The boy sank into a pile of leaves.

“Go ahead and pray, Sam,” Decker said, placing a broad hand on the boy’s shoulder. He reached into his rear pants pocket and pulled out a pack of cigarettes. He’d been trying to cut down, but at this moment he needed a nicotine fix badly.

“And when you’re done,” he said, striking a match, “we’ll go call the police.”

2

They stood like pickets in a fence: Decker, Ed Fordebrand, a homicide cop from the Foothill Division of the LAPD, and Walt Beckham, a deputy county sheriff for the Crestview National Forest Service. The woods were swarming with activity: crime technicians combing the brush for evidence, police photographers popping flashes, the deputy medical examiner barking directions for the removal of the bones. Beckham hitched up his beige uniform pants and sucked on his pipe. Fordebrand started scratching his left arm, which had broken out into welts. Decker glanced at the boys. Jake was standing to one side. His color had returned and now he was fascinated by the action. But Sammy had distanced himself from the commotion and sat huddled under a massive eucalyptus.

“Nice goin’, Deck,” Fordebrand said, rubbing his forearm. “I thought you were on vacation.”

“Fuck you.”

“And a merry Christmas to you, too,” Fordebrand growled.

Decker shrugged.

“Sorry,” he said.

Fordebrand was six two and pure beef: the reincarnation of a Brahma bull.

“You want to take this, Sheriff?” he asked Beckham. “It’s your jurisdiction.”

Beckham tugged a corner of his gray mustache.

“Seems to me it’s right on the border between County and Foothill.”

“Closer to you,” Fordebrand said.

“Detective, how ’bout you and me slicing through the shit,” said Beckham. “You don’t want to do this now. And I don’t want to do this now. We’d both rather be home, downing a brew and singing carols to the Savior.”

“How about a joint operation?” Fordebrand tried. “Cut the paperwork by half.”

“Why don’t you flip a coin?” suggested Decker.

“I like the man’s logic,” Beckham said. He won the toss and smiled. Fordebrand made a last-ditch effort.

“I still think it’s on your side of the border, Sheriff,” he said.

“You’re being a sore loser, Detective,” said Beckham.

“Go home,” Decker said. “We’ll work it out.”

Fordebrand gave Decker a dirty look.

“My replacement’s coming in a half hour,” Beckham said. “I’d appreciate it if you could fill him in. If any questions should come up, who do I call?”

The big bull took out his card and gave it to him.

“Edward,” Beckham said, reading it and sticking out his hand, “it’s been a pleasure.”

Fordebrand grumbled, then pumped the deputy’s hand firmly. “You call and ask for me or call the same extension and ask for Detective Sergeant Decker here—”

“I’m not working Homicide,” Decker said.

Fordebrand smiled cryptically, still digging at his forearm. The rashes and welts were manifestations of an allergic reaction that occured whenever he dealt with corpses—inconvenient, considering his chosen profession.

“If you don’t mind, I’ll leave you gentlemen now,” said Beckham.

“Yeah,” Fordebrand said. “Merry Christmas. Merry fucking Christmas.”

Beckham jogged away and Fordebrand turned to Decker.

“Goddam hillbilly shitheads. What the hell do they do all day? Sit up in the ranger station and jerk their chains?”

“He’s right,” Decker said. “The area does belong to Foothill. He might as well save himself the hassle.”

“Stop being so noble.”

“What’s with the shit-eating grin when I said I wasn’t working Homicide?”

“Well, when you get back you’ll notice that we’re slightly shorthanded.”

“We’ve got five homicide dicks.”

“Pilkington’s transferred to Harbor Division, Marriot’s on vacation, Sleighton’s father took sick in Canada, so he flew out to be with him for the holidays. That leaves me and Bartholemew. I just found out today that Bart broke his leg riding a bicycle.”

“Shit.”

“Morrison did a little rearranging. Starting December twenty-sixth, you and Dunn are working Homicide. Dunn is actually jockeying back and forth between Homicide and Sex and Juvey—”

“I don’t want to hear about this, Ed. I’m still on vacation.” Decker looked at the boys. “Such as it is.”

“Rina’s kids?” Fordebrand asked.

Decker nodded. “The older one found the bones. What a crappy deal! Nice weather, so I take them for a few days in the wild—unpolluted skies, unspoiled nature—and they have to be exposed to this crud.”

“That’s too bad.” Fordebrand’s right arm had begun to swell. He clawed at it and winced. “So you want this one, Deck?”

“All right. Starting the twenty-sixth. Nothing’s going to go down between then and now anyway.”

“Easy case,” Fordebrand said. “Open and shut. Poke around a little just to say you did something. Look through a few Missing Persons files and forget about it. A week’s worth of desk work—nice and clean.”

“If it’s so appealing, Ed, you can take the case.”

“I’ll be happy to, Decker, if you take the packinghouse slashings.”

“Pass.”

Fordebrand ran his fingers through his hair.

“Yeah, you look through a couple of Missing Persons files, then close the books, and they go down in the annals as a couple of John Does.”

“Jane Does,” Decker said. “They look like females to me.”

“Jane Does, John Does, who the hell cares? Nobody’ll hear from ’em again.” Fordebrand slapped him on the back. “I’ll handle the preliminary garbage. You go off and finish your vacation. Take care of the boys.”

“Sorry I had to drag you out on Christmas Eve.”

“Ah, it’s okay,” Fordebrand said magnanimously. “I’ll be back in time for the honey-glazed ham and the turkey. The ham’s in the oven; the turkey’s coming in from Cleveland.”

Decker smiled. “Your mother-in-law?”

“Who else?”

“Have fun.”

“If you get lonely tonight, Deck—”

“I’ll be up here with the boys, but thanks anyway.”

Fordebrand nodded.

“Yeah, you probably don’t go in for Christmas anymore, do you, Rabbi?”

Decker shrugged.

“You like playing Daddy, Deck?”

“They’re good kids.”

“What’s with you and their mama anyway?”

“Beats me, Ed.”

Decker called out to Jake, and jogged over to Sammy and sat down beside him. The younger boy came running and jumped onto Decker’s lap.

“The police will take it from here, guys, so we can go back to the campsite now. We’d better get going. We still have to pitch the tent—”

“Peter, I want to go home,” said Sammy.

Decker blew out air forcefully. “All right. Is that okay with you, Jakey?”

“Yeah, I’d like to go home, too. I’m sick of peanut butter.”

Decker put his arms around the boys. “I’m awfully sorry, guys.”

Sammy leaned his head on the detective’s shoulder. “It wasn’t your fault.”

“Are you guys a little spooked?”

“Maybe a little,” Sammy answered.

“How about you, Jake?”

Jacob shrugged.

“It’s a normal feeling to be freaked out. You kids handled this very well.” Decker helped them to their feet. “Let’s go pack up. I hope you guys had a good time before all this happened.”

“I did,” Sammy said. “I really really did.”

It was hard to tell whether he was convincing Decker or himself.

Decker drove them home in the jeep. The boys said nothing as they rode down the winding, one-lane dirt paths with five-hundred-foot drops bouncing along bumpy mountain roads. When the four-wheeler finally exited the mountain highway and hooked onto the freeway on-ramp, Sammy let out a big sigh.

“Do you ever worry about getting killed?” he asked Decker.

“I used to when I was a uniformed policeman, but not anymore, Sammy. My work is pretty safe. It’s mostly pushing papers and talking to people.”

“Were you ever shot?” the older boy continued.

“No.”

There was a brief silence.

“I don’t know what I want to be when I grow up, but I don’t want to be a cop.”

Decker nodded. “It can get pretty gross sometimes.”

“Know what I want to be?” said Jake.

“What?” the big man asked.

“A pilot in the Israeli Air Force.”

“Not me,” said Sammy. “I don’t want to get killed.”

“They never get killed,” Jake protested.

“’Course they get killed, Yonkie. The Arabs are shooting at you. You think they don’t get lucky and get a hit once in a while?”

“Well, I’m not gonna get killed!” Jake said firmly.

“Yeah! Right!”

Silence.

“I don’t know what I want to do,” Sammy pondered. “I’d like to get smicha, but I don’t want to learn full time like my abba or my uncles did.”

“Are all your uncles rabbis?” asked Decker.

“All except one,” answered Sammy. “One of my eema’s brothers lives in Jerusalem. He’s a sofer. That’s kind of interesting I guess.”

“What’s that?” Decker asked.

“Uh, you know, the guy who writes the Torah and the mezuzahs,” explained Sammy.

“A scribe,” Decker said.

“Yeah, I think that’s what they call them,” said Sammy. “My other uncles, the ones married to my abba’s sisters, used to teach in yeshiva, but now they’re businessmen. They live in New York.”

“We’ve got tons of family there,” Jake said, excitedly. “We’ve got a bubbe and zayde and two great-grandmothers, and a whole bunch of cousins. We’re not alone at all.”

Then the little boy licked his lips and frowned. “But sometimes it feels like it.”

“Especially when you see scary stuff like today?” said Decker.

“Aw, that doesn’t bother me,” Jake said mustering up bravado. “That was kinda neat … kind of.”

“Eema’s other brother, the one that’s not a rabbi, sees dead bodies all the time,” Sammy said. “He’s a pathologist and owns cemeteries … Anyway, him and Eema get into fights about that all the time because he’s a kohain—a Jewish priest—and kohains aren’t supposed to to be around corpses.”

“Your uncle’s not religious?” Decker asked.

Sammy nodded. “Him and Eema fight about that, too. You can bet that we don’t see much of Uncle Robert.”

They rode another mile in silence. Decker broke it.

“Are you interested in medicine, Sammy?” he asked.

“No way,” Sammy answered. “I don’t like blood.”

“How about business? Like your New York uncles?”

“Borrrrring,” said Sammy.

Decker smiled.

“Well, you boys have plenty of time to figure out what you want to be. Heck, it’s okay to do a lot of different things in a lifetime. I used to do ranching when I was a kid in Florida. I did construction work in high school. I was a lawyer for a while, and I don’t see myself as being a cop forever. You’ve got loads of time to experiment.”

Sammy mulled that over for a while.

“You know what I’d like to be?” he said. “I think I’d like to be a journalist. Maybe write editorials that make people think.”

The kid was all of eight and a half.

The grounds of Yeshivas Ohavei Torah were located on twenty acres of brush and woodland in the pocket community of Deep Canyon. It was twenty freeway minutes from the police station and fifteen minutes from Decker’s ranch. The locals of Deep Canyon were working-class whites, and they and the Jews had little to do with each other, but over the past few years there had grown an uneasy, mutual tolerance.

The locals weren’t the only ones who felt uncomfortable with the Jewish community. The Foothill cops were equally baffled by the enclave, imagining it a slice of old Eastern Europe that had been frozen in a time warp. Actually, the yeshiva embodied aspects of both past and present, but the cops never delved that deeply. They had nicknamed the place Jewtown, which is what Decker had called it before his own personal involvement. Now, at least when Decker was around, they referred to it by its rightful name.

The lot for the yeshiva had been cut out of the mountainside. Huge boulders had been hauled away and the ground had been leveled, leaving a mesa of flat land surrounded by thick foliage, evergreens, and hillside. Set in the middle of a broad carpet of lawn was the main building—a two-story cement cube that contained most of the classrooms. On one side were smaller buildings—additional classrooms, the library, the synagogue, and the ritual bathhouse. The other side was open space for a thousand feet, then housing—a dormitory and a cluster of prefab bungalows.

Most of the yeshiva residents were college-age boys engaged in religious studies, but the place also had a high school, with secular and Jewish curricula, and an elementary school for children of the kollel students—married men studying Talmud full time. Private homes were provided for the kollel families, the two dozen rabbis who served as full-time teachers, and the headmaster—the Rosh Yeshiva. He was a meticulously dressed, distinguished man in his seventies named Rav Aaron Schulman. Rina’s husband had been his protégé and most brilliant student. Because of that, she and her sons had been allowed to stay on after he died.

Rina had once admitted to Decker that she was an outsider at the yeshiva. The women who lived on the grounds simply came along with their husbands or fathers. The school catered exclusively to men, and as a widow, she had no role there whatsoever. Though the residents treated her kindly—it was demanded of them by the Torah—she still felt like an interloper living in free housing, even though she taught math at the high school and operated the ritual bath. She knew she’d have to leave one day, but in the meantime she was grateful for the interlude that let her try to figure out what to do with the rest of her life.

Decker parked in front of the main gate, told Ginger to stay, and walked with the boys across the lawn. The place was almost empty at this time of the year; most of the boys had gone home to their families. Still, a seminar was being held on the grass. A full-bearded rabbi wearing a black suit and hat sat with five pupils—bochrim—under an elm. The students and their teacher were engaged in animated dialogue. Decker and the kids walked down the main pathway, turned onto a dirt sidewalk that cut through the residential portion, and stopped in front of a white bungalow.

“I’d appreciate it if you boys didn’t mention the bones until after I’ve spoken with your mother.”

They nodded.

Rina opened the door at Decker’s knock, her eyes widening with surprise, lips opening in a full smile.

“I didn’t expect you guys back until tomorrow!”

Sammy fell into his mother’s arms and embraced her tightly. He leaned his head against her breast and hid his gaze from hers. Rina cupped his face in her palms and looked at him, noticing moisture in his eyes and the tremble of his lower lip. She kissed him on his forehead and he broke away. Jake gave her a playful hug and smothered her face with kisses.

“I think they missed you,” Decker said.

“Happy to be home?” she asked them as they went inside.

The boys nodded.

“I’ve got surprises for you both. They’re on your beds.”

“Oh boy!” Jake exclaimed, heading for the bedroom. Sammy lagged behind.

“Shmuel,” she said, holding his arm, “is everything okay?”

He nodded.

“Something’s bothering you.”

“I’m fine, Eema. I’m just tired.”

“Okay,” said Rina, disconcerted at his evasion.

He gave his mother another hug, then trudged off to the bedroom.

“What happened?” she asked Peter as soon as they were alone.

“Could I have a cup of coffee, Rina?”

“Uh … Uh. Of course,” she said. “Sit down, Peter. You look exhausted.”

He took a seat on the left side of her brown sofa, letting his head flop back against the cushion, then ran his hands over his face.

“Why are the boys upset?” she asked.