Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «The Ritual Bath»

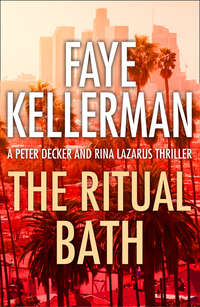

The Ritual Bath

Faye Kellerman

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in the United States by William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers, 1986

This ebook edition published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © Faye Kellerman 1986

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover photography © Shutterstock.com

Faye Kellerman asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © March 2019 ISBN: 9780008293536

Version: 2018-11-05

Dedication

For Jonathan. Ani l’dodi  dodi li.

dodi li.

And for the munchkins:

Jesse, Rachel, and Ilana.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Keep Reading

About the Author

Faye Kellerman booklist

About the Publisher

1

1

“The key to a good potato kugel is good potatoes,” Sarah Libba shouted over the noise of the blow dryer. “The key to a great potato kugel is the amount of oil. You have to use just enough oil to make the batter moist, plus a little excess to leak out around the cake pan and fry the edges to make the whole thing nice and crisp without being too greasy.”

Rina nodded and folded a towel. If anyone would know how to cook a potato kugel, it was Sarah Libba. The woman could roast a shoe and turn it into a delicacy. But tonight Rina was too fatigued to listen with a full ear. It was already close to ten o’clock, and she still had to clean the mikvah, then grade thirty papers.

It had been a busy evening because of the bride. A lot of to-do, hand-holding, and explaining. The young girl had been very nervous, but who wouldn’t be about marriage? Rivki was barely seventeen with little knowledge of the world around her. Sheltered and exquisitely shy, she’d gotten engaged to Baruch after three dates. But Rina thought it was a good match. Baruch was a good student and kind and very patient. He’d never once lost his temper while teaching Shmuel how to ride a two-wheeler. He’d be calm yet encouraging, Rina decided, and it wouldn’t be long before Rivki knew the ropes just like the rest of them.

Sarah shut off the dryer, and the motor belched a final wheeze. Fluffing up her close-cropped hair, she sighed and placed a wig atop her head. The nylon tresses were ebony and long, falling past Sarah Libba’s slender shoulders. She was a pretty woman with wide brown eyes that lit up a round, friendly face. And short, not more than five feet, with a slim figure that belied the fact that she’d borne four children. Meticulous in dress and habit, she worked methodically, combing and styling the artificial black strands.

“Here,” Rina said. “Let me help you with the back.”

Sarah smiled. “Know what inspired me to buy this shaytel?”

Rina shook her head.

“Your hair, Rina,” said Sarah. “It’s getting so long.”

“I know. Chana’s already mentioned it to me.”

“Are you going to cut it?”

“Probably.”

“Not too short I hope.”

Rina shrugged. Her hair was one of her best features. Her mother had raised a commotion when she’d announced her plans to cover it after marriage. Of all the religious obligations that Rina had decided to take on, the covering of her hair was the one that displeased her mother the most. But she forged ahead over her mother’s protests, clipped her hair short, and hid it under a wig or scarf. Now, of course, the point was moot.

Working quickly and with self-assurance, Rina turned the wig into a fashionable style. Sarah Libba craned her neck to see the back in the mirror, then smiled.

“It’s lovely,” she said, patting Rina’s hand.

“I’ve got a lot to work with,” said Rina. “It’s a good shaytel.”

“It should be,” Sarah said. “It cost nearly three hundred dollars, and that’s for only twenty percent human hair.”

“You’d never know.”

The other woman frowned.

“Don’t cut your hair short, Rina, despite what Chana tells you. She has a load of advice for everyone but herself. We had the family over for Shabbos and her kids were monsters. They broke Chaim’s Transformer, and do you think she offered a word of apology?”

“Nothing, huh.”

“Nothing! The boys are vilde chayas, and the girls aren’t much better. For someone who runs everyone else’s life, she sure doesn’t do too well with her own.”

Rina said nothing. She wasn’t much of a gossip, not only because of the strict prohibitions against it, but because she found it personally distasteful. She preferred to keep her opinions to herself.

Sarah didn’t prolong the one-way conversation. She stood up, walked over to the full-length mirror, and preened.

“This time alone is my only respite,” she said. “It makes me feel human again.”

Rina nodded sympathetically.

“The kids will probably all be up when I get home,” the tiny woman sighed. “And Zvi is learning late tonight … I think I’ll walk home very slowly. Enjoy the fresh air.”

“That’s a good idea,” Rina said, smiling.

Sarah trudged to the door, turned the knob, straightened her stance, and left.

Alone at last, Rina stood up, stretched, and glanced at her watch again. Her own boys were still at the Computer Club. Steve would walk them home to a waiting baby-sitter so there was no need to rush. She could take her time. Removing her shoes, she rubbed her feet, slipped them into knitted socks and shuffled along the gleaming white tile. Loaded down with a bucket full of soapy water, a handful of rags, and a pail of supplies, she entered the hallway leading to the two bathrooms.

The first one had been used by Sarah Libba, who’d left it neat and orderly. The towels and sheet were compulsively folded upon the tiled counter, the bath mat draped over the rim of the bathtub, and care had been taken to remove the hairs from the comb and brush.

Rina quickly went to work, scrubbing the floor, tub, wash basin, and shower. She refilled the soap containers, the Q-tips holder, the cotton ball dispenser, recapped the toothpaste, and placed the comb in a vial of disinfectant. After giving the countertops a thorough going-over, she left the room, taking the garbage and the dirty laundry with her.

The second bathroom was in complete disarray but within a short period of time, it was as spotless as the first.

She dumped the garbage down a chute that emptied into a bin outside and loaded the towels, sheets, and washcloths into a large utility washer in the closet. Now for the mikvot themselves.

The main mikvah—the women’s—was a sunken Roman bath four feet deep and seven feet square, covered with sparkling, deep blue tile. To aid the women in climbing down the eight steps, a handrail had been installed. Religious law prescribed that the water in the bath emanate from a natural source—rain, snow, ice—but the crystalline pool was heated for comfort.

What a beautiful mikvah, Rina thought, so unlike the one she’d used in an emergency six years ago. They’d been visiting Yitzchak’s parents in Brooklyn. It had been wintertime and blizzard warnings were out. The closest mikvah was nothing more than a hole of filthy, freezing water, but she’d held her breath and forced herself to dunk anyway. She’d felt contaminated when she got home. Though bathing wasn’t permissible after the ritual immersion, Yitzchak had looked the other way when she soaked her chilled bones in steaming water to clean off the scummy residue left on her skin.

The wives of the men at the yeshiva had been very vocal about constructing a clean mikvah—one that would make a woman proud to observe the laws of family purity. And they’d gotten their way. The tile used for the mikvah and bathroom countertops was handpicked and imported from Italy. As an extra touch, a beauty area was added, complete with two vanity tables fully equipped with dryers, combs, brushes, curling irons, and make-up mirrors. An architect was hired, the construction progressed rapidly, and now the yeshiva had a mikvah to call its own. No longer would the women have to travel hours to do the mitzvah of Taharat Hamishpacha—spiritual cleansing through dunking in the ritual bath.

Rina mopped the excess water off the floor, then turned off the heat and lights. She padded down the hallway, took out a key and went inside the men’s mikvah. It was comparatively unadorned, layered with plain white tile. The men had refused to heat or filter the water, but the Rosh Yeshiva was very insistent that they keep the place clean. Though she didn’t have to, she mopped the floor as a courtesy.

When that was done, she relocked the door and finished off by cleaning the last pool—a small basin for dunking cooking and eating utensils made out of metal. A frying pan lay at the bottom. Ruthie Zipperstein must have left it when she had dunked her cookware. Rina would drop it off on her way home.

She dried her hands, then went back to the reception room and sat down in an old overstuffed chair. Taking out a stack of papers, she began to grade them to the low hum of the washing machine. She’d gone through half the pile when the cycle finished. As she got up to load the dryer she heard a shriek that startled her.

Cats, she thought. The grounds of the yeshiva were inundated with them. Scrawny felines that made horrible human-like cries, scaring her sons in the middle of the night. She slammed the door to the dryer and was about to turn on the motor when she heard the shriek again. Walking over to the door, she leaned her ear against the soft pine. She could hear something rustling in the brush, but that wasn’t unusual, either. The yeshiva was situated in a rural area and surrounded by forest. The tall trees sheltered a variety of scurrying animals—jackrabbits, deer, squirrels, snakes, lizards, an occasional coyote, and of course, the cats. Still, she began to get spooked.

Turning the knob, Rina opened the door partway and peered into the blackness. A stream of hot air hit her in the face. The sky was star-studded but moonless. She heard nothing at first, then against a background chorus of chirping crickets, the sound of muffled panting. She opened the door a little wider, and a beam of indoor light streaked across the dry, dusty ground.

“Hello?” she called out tentatively.

Silence.

“Is anyone out there?” she tried again.

Out of the corner of her eye, she caught sight of a fleeing figure that disappeared into the thickly wooded hillside. A large animal, she thought at first, but then realized the figure had been upright.

She stood motionless for a brief moment and listened. Did she hear the panting again or was her overactive imagination at work? Shrugging, she was about to close the door when she was seized by panic. On the ground in front of her lay Sarah’s wig, the black tresses tangled and matted.

“Sarah?” she yelled.

The only response was the panting.

She picked up the wig and examined it with shaking hands. Then, very cautiously, she ventured toward the surrounding thickets, moving closer and closer to the sound.

“Sarah, are you out there?” she shouted.

The panting grew louder.

The noise seemed to rise from a bowl-like depression in the heavily wooded area. She went in for a closer look and gasped in horror.

Sarah Libba was sprawled on the ground, caked with dirt. Her dress had been ripped into ribbons. Her small face was wet with ooze that ran down her cheeks and over her naked breast, her legs bare except for the underpants wrapped around her ankles and the sandals on her feet. Sarah’s eyes bulged and convulsed in their sockets, her breaths rapid and shallow. She was on the brink of hyperventilation.

Rina stumbled, caught her balance, then slowly bent down. Sarah cowered, retreating from her approach like a wounded animal. Kneeling down to eye level, Rina saw the fresh bruises on her face.

Sarah balled her hand into a fist and began to pound her breast forcefully. Her eyes entreated the heavens, and she moved her lips in silent supplication. Rina took the woman’s arm and brought her to her feet.

For a small woman, Sarah was surprisingly heavy, and supporting her weight caused Rina to buckle. But somehow she managed to lead the bleating figure inch by inch back into the safe confines of the mikvah. Once inside, she had Sarah lie down. Gently removing the rent clothes, Rina wrapped her bruised and lacerated body in a freshly laundered sheet.

Rina’s first call was to Sarah Libba’s house. She left a message with the baby-sitter to find Sarah’s husband, Zvi, in the study hall and tell him to come to the mikvah immediately. After that she phoned the Rosh Yeshiva. He, of course, was learning also, so she left the same message. Finally, she called the police.

2

2

Decker picked up the phone, and his mouth fell open as he scratched out the details in a small notebook. He knew the day just had to end up as lousy as it started out. First, it was Jan nagging him for more child support, then the entire day was wasted pursuing a dead-end lead on the Foothill rapist because of that call from the flaky broad. Now, as if things weren’t bad enough, a rape at Jewtown.

Jesus, he thought, looking at the piles of paperwork on his desk. The weather gets hot, and the locals take to the streets. Plus, to beat the heat, the women dress scantier and scantier till some weirdo gets it in his head that “they’re all asking for it anyway.” God, he was sick of this detail. He’d considered transferring back to Homicide, tired of seeing rape survivors hung up to dry by a fucked-up—and misnamed—justice system. At least with Homicide the victims never had to face the perpetrators.

But a rape in Jewtown? Few locals, including himself, had ever set foot in the place. The grounds were gated and walled off, and the Jews kept to themselves, rarely venturing into town except to shop at Safeway or maybe get a car fixed. They were different, but they never caused any trouble. Decker wished he had a city full of ’em. He wondered how God’s chosen were going to deal with a rape and didn’t look forward to getting the answer.

He glanced around and found Marge Dunn at the coffeepot. Walking over to the most popular spot in the room, he touched her lightly on the shoulder.

“I need you, babe.”

She turned around, holding a steaming mug of coffee. Her big-boned frame made people think she was a lot older than her twenty-seven years, but that was okay with her. She liked the respect her height and weight brought her. Her face, in contrast, was soft—large bovine eyes and silky wisps of blond hair. She was an enviable combination of toughness and femininity.

“For you, Peter my love, anything.”

“It’s a dandy. A rape just went down at Jewtown.”

Marge put her cup down. “You’re kidding.”

“No such luck.” Decker frowned, then chewed on his mustache. “Let’s move it.”

“Pete, why don’t you let Hollander take the call?” She wiped a bead of sweat from her forehead. “We’re already working overtime with the Foothill thing, and he’s just come off vacation.”

“I’d love to pass this one over to him, but he’s at Dodger Stadium now.”

“So beep the lazy butt.”

“I don’t believe in interrupting a man at a ball game.”

“How about interrupting a woman with a fresh cup of coffee?”

“Let’s go.”

Decker started for the door. Marge grabbed her purse and followed reluctantly. It was the usual pattern: he hotdogging it, and she trying to slow down the big redhead. One thing about Peter, Marge thought, he was a good cop, smart and dedicated. But it worked against him. The brass constantly saddled him with all the rotten cases.

Together they left the station—a dilapidated stucco building, once white, now washed with grayish grime—and walked to the brightly lit parking lot. Flipping Marge the keys to a faded bronze ’79 Plymouth, Decker scrunched into the passenger side and pushed the bench seat back to the maximum. Like a fucking sardine, he thought as his shin grazed the undersurface of the dashboard. One day the Department would have unmarkeds that accommodated someone over six feet. When I’m ready to retire.

He rolled down the window. Jesus, it was hot. Decker could already feel moist circles under his armpits and rivulets of sweat running down his neck and back. He hiked up his shirt sleeves and leaned a thick, freckled arm out the window.

“Scorcher,” Marge said. “Must be hell with your metabolism.”

“I always know when we’re about to get a heat wave,” Decker moaned. “The air-conditioning goes out in the car a week before.”

“A rape in Jewtown,” Marge muttered. “I’ve always thought of the place as sacrosanct. Sort of like a convent. Who’d rape a nun?”

“Who’d rape, period?” Decker said.

“Good point.”

Marge started the engine and eyed him. “You look exceptionally bad tonight, Peter.”

“Thanks for the compliment.”

Marge peeled rubber. “I sure hope this isn’t the first in a string of Jew rapes.”

Decker exhaled audibly, thinking the same thing. Some people had lots of animosity toward the Jews. Their place had been hit several times by vandals, but there hadn’t been any violence against the people themselves. Not until tonight.

“Let’s take it one step at a time, Marge. Maybe there’ll be a logical explanation for the whole thing.”

“I doubt it, Peter,” she said. “There never is.” She drove quickly and competently. “How’re your horses?”

“I just got a pinto filly,” he said, smiling. “A real cutie.”

“How many are you up to now?”

“Lillian makes six.”

“You must shovel lots of shit, Peter.”

“True, but unlike the urban version, it’s biodegradable.” He lit a cigarette. “How’s old Clarence?”

“Speaking of shit,” Marge grumbled.

“Oh?”

“He forgot to tell me about the wife, the two kids, and the dog.”

“The louse.”

“Stop laughing. That’s exactly what he was. As far as I’m concerned he’s dead and buried. You’re not up to date, Pete. My newest is Ernst. He’s a concert violinist for the Glendale Philharmonic. We’ve played some nice flute-violin duets. When I get good enough, I’ll invite you and the lucky date of your choice to a recital.”

“I’d like that.” He smiled at the image of the big woman playing such a delicate instrument. A cello would have seemed more in character. Not that she had any talent. The guy must really be hot for Marge, he thought, to put up with her playing, which Decker had always likened to a horny parrot’s mating call. He couldn’t understand how she could continue with music if her ears heard the same thing that his did. The only logical conclusion was that she was deaf and had maintained the secret all these years by artful lip reading.

Marge turned onto TWO HUNDRED TEN East, and the Plymouth grunted as it picked up speed.

Decker dragged on his cigarette, looked out the window, and surveyed his turf. Los Angeles conjured up all sorts of images, he thought: the tinsel and glitter of the movie industry, the lapping waves and beach bunnies of Malibu, decadent dope parties and extravagant shopping sprees in Beverly Hills. What it didn’t conjure up was the terrain through which they were riding.

The area encompassing Foothill Division was the city’s neglected child. It lacked the glamour of West L.A., the ethnicity of the east side, the funk of Venice beach, the suburban complacency of the Valley.

What it did have was lots of crime.

Bordering and surrounding other cities, each with a separate police department, Foothill’s domain could best be described as a mixture of small, depressed towns segregated from each other by mountains and scrub. Some of the pocket communities housed lower-class whites, biker gangs, and displaced cowboys, others were ghettos for blacks and migrant Hispanics, but most had a common denominator—poverty. People scratching by, people not getting by at all. Even Jewtown. These people weren’t the wealthy Jews portrayed by the media. It was possible that the yeshiva held a secret cache of diamonds, but you’d never know it by looking at its inhabitants. They dressed cheaply, buying most of their clothes at Target or Zody’s, and drove broken-down cars like the rest of the locals.

The station was twenty freeway minutes away from the yeshiva—a quick ride along a serpentine strip of road cut into the San Gabriel mountains. In the dark, the hillside lurked over the asphalt, casting giant shadows. The air in the canyon was hot and stagnant, but as the Plymouth sped along, a cool jet stream churned through the open windows.

“I’m glad you were available,” Decker said. “You do a hell of an interview.”

“Sensitivity, Peter. That’s why I work so well with the kids in Juvey. Being a victim of life myself, I know how to talk to people who have been thoroughly fucked up. Like you, for instance.”

Decker smiled and crushed the cigarette butt in the overflowing ashtray. “Is that an example of your sensitivity?”

“At its finest.” Marge’s face grew stern. “I’m not looking forward to this. The Jews don’t relate well to outsiders.”

“No, they don’t,” he agreed. “But rape survivors experience lots of common feelings. Maybe that’ll supersede the xenophobic inclinations.”

“Yes sir, Professor,” said Marge, saluting. She pulled onto a winding turn-off ramp marked Deep Canyon Thoroughfare, Deep Canyon. The “thoroughfare” was a two-lane road blemished with dips and bumps. The unmarked car bounced along for a mile, until the street turned into a newly paved four-lane stretch.

They cruised slowly for another mile, inspecting the street with cops’ wariness. Scores of local kids were hanging out in front of the 7-Eleven, sitting on the hoods of souped-up cars while smoking and drinking. Their raucous laughter and curses sounded intermittently above ghetto-blasters wailing in the hot night air. While the teenagers filled themselves with Slurpees and Coke, their elders tanked up on Jim Beam or Old Grand Dad at the Goodtimes Tavern. The place was doing a bang-up business judging from the number of cars parked in the lot.

In front of the Adult Love bookstore, a group of bikers congregated, decked out in leather and metal. The ass-kickers leaned lazily against their gleaming choppers and stared at the unmarked as it drove by.

As they headed north the activity began to thin. They passed a scrap metal dealership, a building supply wholesaler, a discount supermarket, and a caravan of churches. Poor people were always attracted to God, Decker mused. The area was a natural for a yeshiva—except for the anti-Semitism.

The street narrowed and worked its way into the hillside, the landscape changing abruptly from urban to rural. Heavy thickets of brush and trees flanked the Plymouth, occasionally scraping its sides as it meandered through the mountains. Two miles farther was another turn-off, then the property line of Yeshivat Ohavei Torah.

Marge pulled the car onto a dirt clearing and parked. Decker stepped outside, took a deep breath, and stretched. The dry air singed his throat.

“Gate should be open,” Marge said. “The place is all walled in, but they always leave the gate open.”

“They’ve been vandalized at least twice and you can’t get them to put a lock on the damn gate.” Decker shook the wire fence. “This is just a psychological barrier, anyway. Wouldn’t stop a serious intruder.”

He pushed open the gate and walked inside. “Let’s get on with it.”

The grounds of the yeshiva were well tended but sparsely planted. A huge, flat expanse of lawn was surrounded by low brush and several flat-roofed buildings. Across the lawn, directly in their field of vision, was the largest—a two-story cube of cement. To its right were a stucco annex off the main building, a nest of tiny tract homes, and a gravel lot speckled with cars, to its left, two smaller bungalow-like structures. Behind the houses and buildings were dense woodlands rising to barren, mountainous terrain.

Decker gave the area a quick once-over. The rapist could have entered the grounds anywhere and exited into the backlands. They’d never be able to find him. Unless, of course, he was someone from the inside.

The two detectives walked on a dimly lit path that ran the length of the lawn.

“Where are we going, Peter?”

Decker looked around and saw two figures approaching. They were dressed in black pants, white long-sleeved shirts, and black hats. They must be dying in the heat, he thought. As they drew closer, he saw that both of the men were young—barely out of their teens—and thin, with short beards and glasses. They walked in a peculiar manner, clasping their hands behind their backs instead of swinging them naturally at their sides.

“Excuse me,” Decker said, taking out his shield.

One of the men, the taller of the two, squinted and read the badge. “Yes, Detective? Is anything wrong?”

“Can you please direct us to the bathhouse?” Decker asked.

Both of the boys broke into laughter.

“I think you’re in the wrong place,” the shorter one said, smiling.

“Try Hollywood,” the taller one suggested.

Decker was annoyed. “We received a report that an incident took place here, at the bathhouse.”

“An incident?” said the short one in a grave voice. “You mean a criminal incident?”

“Do you think they mean the mikvah?” the taller one asked his friend, then turned to Decker: “You mean the mikvah?”

“Maybe you should direct us to this mikvah,” Marge said.

“You can’t go there now,” the tall one said to Decker. “It’s only open to women at this time of night.”

The short one prodded him. “The incident obviously has to do with the mikvah.” He looked at Decker and asked, “Was anyone hurt?”

“Stop asking them questions and answer theirs,” his friend scolded, then said to Decker: “The mikvah is that little building in the corner.”

“Thank you,” Marge answered, walking away.

“I hope it’s nothing serious,” the big one added.

Decker gave them a smile, but not a reassuring one.

They walked a few steps, then Marge said, “Notice how they looked at me?”

“They didn’t.”

“That’s what I’m saying.”

They’d arrived before the black-and-whites.

Marge knocked on the door and a young dark-haired woman opened it, allowing them to enter after a flash of badges. Immediately, the murmuring that had filled the room died. The detectives were greeted with icy, suspicious stares from four kerchief-headed women crammed into the reception area. In the corner, an elderly bearded man who looked like a rabbi was whispering into the ear of a younger man who was rapidly rocking back and forth.

The young woman motioned them outside.

“I’m Rina Lazarus, the one who called the police,” she said. “The women inside were here earlier tonight. We’ve called a meeting to find out if anyone heard or saw anything unusual on their way home. Unfortunately, no one did.”

“What happened?” Decker asked.

She hesitated and looked around. “A woman was raped.”

“Where is she?” Marge asked.

“With one of the women in a dressing room. She’s about to take a bath—”

“She can’t do that until she’s been examined,” said Marge sharply.

“I know,” Rina said. “The officer I spoke to over the phone mentioned that, but I don’t know if she’s going to be willing to have herself examined.”

Marge eyed Decker, then said: “I’ll talk to her.” Turning to Rina, she asked: “What’s her name?”

“Sarah Libba Adler.”

“Miss or Mrs.?”

“Mrs.”

“Is she dressed?” asked Marge.

“I’m not sure. Her husband brought her a change of clothes, but I don’t know if she put them on yet. You’ll have to knock on the door to the bathroom and ask.”

“Where are the original clothes?” Decker asked.

“In a paper sack to the left of the bathhouse door. They’re nothing more than shreds but I thought you might want them.”

“We do,” Marge said. She slapped Peter on the back and disappeared inside.

Rina wasn’t comfortable being alone with a man, even a detective, and suggested they go back inside. That was fine with Decker since the mikvah was air-conditioned. Then seeing two uniforms coming toward the building, Decker motioned them over. He excused himself for a moment, then brought the policemen back to Rina.

Tasuta katkend on lõppenud.