Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «A Place of Greater Safety»

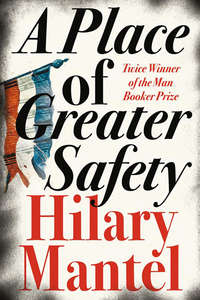

HILARY MANTEL

A Place of Greater Safety

Copyright

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

Paperback edition first published by Harper Perennial 2007

First published in Great Britain by Viking 1992

Copyright © Hilary Mantel 1992

Hilary Mantel asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

PS section copyright © Sarah O’Reilly 2010

PS™ is a trademark of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN 9780007250554

Ebook Edition © NOVEMBER 2009 ISBN: 9780007354849

Version: 2017-02-13

Praise

From the reviews of A Place of Greater Safety:

‘Crafty tensions, twists and high drama … a bravura display of her endlessly inventive, eerily observant style’

Times Literary Supplement

‘A formidably talented novelist … She has seen deeply into her characters and their involvements with one another, and makes them live for us, with vivid invented detail, day by day, as they are battered or seduced by public events’

London Review of Books

‘Much, much more than an historical novel, this is an addictive study of power, and the price that must be paid for it … a triumph’

Cosmopolitan

‘Intriguing … She has grasped what made these young revolutionaries – and with them the French Revolution – tick … This is the perfect complement to Simon Schama’s history of the French Revolution, Citizens’

Independent

‘Concentrating on the tortuously interwoven relationship between its three most important protagonists, Robespierre, Danton and Desmoulins, Hilary Mantel has pulled off the apparently impossible … an ambitious, gripping epic … The host of minor characters and the swirling mob who form the necessary background to the story are never lost from sight, but are expertly marshalled on and off the bloodstained stage … a tour de force of the historical imagination’

Vogue

‘Mantel’s grasp both of detail and the complex sweep of events is quite remarkable …“her people” are firmly rooted in physical and historical reality … Little is known of the personal lives of most revolutionary leaders before 1789, and after they became famous, they lived constantly in the public eye. Yet Mantel has managed to get inside them by feeling her way through their writings, families and, quite brilliantly, their women’

Times Literary Supplement

Dedication

To Clare Boylan

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

Author’s Note

Cast of Characters

Map of Revolutionary Paris

PART ONE

I. Life as a Battlefield (1763–1774)

II. Corpse-Candle (1774–1780)

III. At Maître Vinot’s (1780)

PART TWO

I. The Theory of Ambition (1784–1787)

II. Rue Condé: Thursday Afternoon (1787)

III. Maximilien: Life and Times (1787)

IV. A Wedding, a Riot, a Prince of the Blood (1787–1788)

V. A New Profession (1788)

VI. Last Days of Titonville (1789)

VII. Killing Time (1789)

PART THREE

I. Virgins (1789)

II. Liberty, Gaiety, Royal Democracy (1790)

III. Lady’s Pleasure (1791)

IV. More Acts of the Apostles (1791)

PART FOUR

I. A Lucky Hand (1791)

II. Danton: His Portrait Made (1791)

III. Three Blades, Two in Reserve (1791–1792)

IV. The Tactics of a Bull (1792)

V. Burning the Bodies (1792)

PART FIVE

I. Conspirators (1792)

II. Robespierricide (1792)

III. The Visible Exercise of Power (1792–1793)

IV. Blackmail (1793)

V. A Martyr, a King, a Child (1793)

VI. A Secret History (1793)

VII. Carnivores (1793)

VIII. Imperfect Contrition (1793)

IX. East Indians (1793)

X. The Marquis Calls (1793)

XI. The Old Cordeliers (1793–1794)

XII. Ambivalence (1794)

XIII. Conditional Absolution (1794)

Note

Keep Reading

Excerpt from Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel

P.S. Ideas, interviews & features …

About the author

A Kind of Alchemy

Life at a Glance

A Writing Life

Read on

Have You Read?

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

Author’s Note

THIS IS A NOVEL about the French Revolution. Almost all the characters in it are real people and it is closely tied to historical facts – as far as those facts are agreed, which isn’t really very far. It is not an overview or a complete account of the Revolution. The story centres on Paris; what happens in the provinces is outside its scope, and so for the most part are military events.

My main characters were not famous until the Revolution made them so, and not much is known about their early lives. I have used what there is, and made educated guesses about the rest.

This is not, either, an impartial account. I have tried to see the world as my people saw it, and they had their own prejudices and opinions. Where I can, I have used their real words – from recorded speeches or preserved writings – and woven them into my own dialogue. I have been guided by a belief that what goes on to the record is often tried out earlier, off the record.

There is one character who may puzzle the reader, because he has a tangential, peculiar role in this book. Everyone knows this about Jean-Paul Marat: he was stabbed to death in his bath by a pretty girl. His death we can be sure of, but almost everything in his life is open to interpretation. Dr Marat was twenty years older than my main characters, and had a long and interesting pre-revolutionary career. I did not feel that I could deal with it without unbalancing the book, so I have made him the guest star, his appearances few but piquant. I hope to write about Dr Marat at some future date. Any such novel would subvert the view of history which I offer here. In the course of writing this book I have had many arguments with myself, about what history really is. But you must state a case, I think, before you can plead against it.

The events of the book are complicated, so the need to dramatize and the need to explain must be set against each other. Anyone who writes a novel of this type is vulnerable to the complaints of pedants. Three small points will illustrate how, without falsifying, I have tried to make life easier.

When I am describing pre-revolutionary Paris, I talk about ‘the police’. This is a simplification. There were several bodies charged with law enforcement. It would be tedious, though, to hold up the story every time there is a riot, to tell the reader which one is on the scene.

Again, why do I call the Hôtel de Ville ‘City Hall’? In Britain, the term ‘Town Hall’ conjures up a picture of comfortable aldermen patting their paunches and talking about Christmas decorations or litter bins. I wanted to convey a more vital, American idea; power resides at City Hall.

A smaller point still: my characters have their dinner and their supper at variable times. The fashionable Parisian dined between three and five in the afternoon, and took supper at ten or eleven o’clock. But if the latter meal is attended with a degree of formality, I’ve called it ‘dinner’. On the whole, the people in this book keep late hours. If they’re doing something at three o’clock, it’s usually three in the morning.

I am very conscious that a novel is a cooperative effort, a joint venture between writer and reader. I purvey my own version of events, but facts change according to your viewpoint. Of course, my characters did not have the blessing of hindsight; they lived from day to day, as best they could. I am not trying to persuade my reader to view events in a particular way, or to draw any particular lessons from them. I have tried to write a novel that gives the reader scope to change opinions, change sympathies: a book that one can think and live inside. The reader may ask how to tell fact from fiction. A rough guide: anything that seems particularly unlikely is probably true.

Cast of Characters

PART I

In Guise:

Jean-Nicolas Desmoulins, a lawyer

Madeleine, his wife

Camille, his eldest son (b. 1760)

Elisabeth, his daughter

Henriette, his daughter (died aged nine)

Armand, his son

Anne-Clothilde, his daughter

Clément, his youngest son

| Adrien de ViefvilleJean-Louis de Viefville |  | their snobbish relations |

The Prince de Condé, premier nobleman of the district and a client of Jean-Nicolas Desmoulins

In Arcis-sur-Aube:

Marie-Madeleine Danton, a widow, who marries

Jean Recordain, an inventor

Georges-Jacques, her son (b. 1759)

Anne Madeleine, her daughter

Pierrette, her daughter

Marie-Cécile, her daughter, who becomes a nun

In Arras:

François de Robespierre, a lawyer

Maximilien, his son (b. 1758)

Charlotte, his daughter

Henriette, his daughter (died aged nineteen)

Augustin, his younger son

Jacqueline, his wife, née Carraut, who dies after giving birth to a fifth child

Grandfather Carraut, a brewer

| Aunt EulalieAunt Henriette |  | François de Robespierre’s sisters |

In Paris, at Louis-le-Grand:

Father Poignard, the principal – a liberal minded man

Father Proyart, the deputy principal – not at all a liberal-minded man

Father Herivaux, a teacher of classical languages

Louis Suleau, a student

Stanislas Fréron, a very well-connected student, known as ‘Rabbit’

In Troyes:

Fabre d’Églantine, an unemployed genius

PART II

In Paris:

Maître Vinot, a lawyer in whose chambers Georges-Jacques Danton is a pupil

Maître Perrin, a lawyer in whose chambers Camille Desmoulins is a pupil

Jean-Marie Hérault de Séchelles, a young nobleman and legal dignitary

François-Jérôme Charpentier, a café owner and Inspector of Taxes

Angélique (Angelica) his Italian wife

Gabrielle, his daughter

Françoise-Julie Duhauttoir, Georges-Jacques Danton’s mistress

At the rue Condé:

Claude Duplessis, a senior civil servant

Annette, his wife

| AdèleLucile |  | his daughters |

Abbé Laudréville, Annette’s confessor, a go-between

In Guise:

Rose-Fleur Godard, Camille Desmoulins’s fiancée

In Arras:

Joseph Fouché, a teacher, Charlotte de Robespierre’s beau

Lazare Carnot, a military engineer, a friend of Maximilien de Robespierre

Anaïs Deshorties, a nice girl whose relatives want her to marry Maximilien de Robespierre

Louise de Kéralio, a novelist: who goes to Paris, marries François Robert and edits a newspaper

Hermann, a lawyer, a friend of Maximilien de Robespierre

The Orléanists:

Philippe, Duke of Orléans, cousin of King Louis XVI

Félicité de Genlis, an author – his ex-mistress, now Governor of his children

Charles-Alexis Brulard de Sillery, Comte de Genlis – Félicité’s husband, a former naval officer, a gambler

Pierre Choderlos de Laclos, a novelist, the Duke’s secretary

Agnès de Buffon, the Duke’s mistress

Grace Elliot, the Duke’s ex-mistress, a spy for the British Foreign Office

Axel von Fersen, the Queen’s lover

At Danton’s chambers:

Jules Paré, his clerk

François Deforgues, his clerk

Billaud-Varennes, his part-time clerk, a man of sour temperament

At the Cour du Commerce:

Mme Gély, who lives upstairs from Georges-Jacques and Gabrielle Danton

Antoine, her husband

Louise, her daughter

| Catherine Marie |  | the Dantons’ servants |

Legendre, a master butcher, a neighbour of the Dantons

François Robert, a lecturer in law: marries Louise de Kéralio, opens a delicatessen, and later becomes a radical journalist

René Hébert, a theatre box-office clerk

Anne Théroigne, a singer

In the National Assembly:

Antoine Barnave, a deputy: at first a radical, later a royalist

Jérôme Pétion, a radical deputy, later called a ‘Brissotin’

Dr Guillotin, an expert on public health

Jean-Sylvain Bailly, an astronomer, later Mayor of Paris.

Honoré-Gabriel Riquetti, Comte de Mirabeau, a renegade aristocrat sitting for the Commons, or Third Estate

Teutch, Mirabeau’s valet

| ClavièreDumontDuroveray |  | His ‘slaves’, Genevan politicians in exile |

Jean-Pierre Brissot, a journalist

Momoro, a printer

Réveillon, owner of a wallpaper factory

Hanriot, owner of a saltpetre works

De Launay, Governor of the Bastille

PART III

M. Soulès, temporary Governor of the Bastille

The Marquis de Lafayette, Commander of the National Guard

Jean-Paul Marat, a journalist, editor of the People’s Friend

Arthur Dillon, Governor of Tobago and a general in the French army; a friend of Camille Desmoulins

Louis-Sébastien Mercier, a well-known author

Collot d’Herbois, a playwright

Father Pancemont, a truculent priest

Father Bérardier, a gullible priest

Caroline Rémy, an actress

Père Duchesne, a furnace-maker: fictitious alter ego of René. Hébert, box-office clerk turned journalist

Antoine Saint-Just, a disaffected poet, acquainted with or related to Camille Desmoulins

Jean-Marie Roland, an elderly ex-civil servant

Manon Roland, his young wife, a writer

François-Léonard Buzot, a deputy, member of the Jacobin Club and friend of the Rolands

Jean-Baptiste Louvet, a novelist, Jacobin, friend of the Rolands

PART IV

At the rue Saint-Honoré:

Maurice Duplay, a master carpenter

Françoise Duplay, his wife

Eléonore, an art student, his eldest daughter

Victoire, his daughter

Elisabeth (Babette), his youngest daughter

Charles Dumouriez, a general, sometime Foreign Minister

Antoine Fouquier-Tinville, a lawyer; Camille Desmoulins’s cousin

Jeanette, the Desmoulins’s servant

PART V

Politicians described as ‘Brissotins’ or ‘Girondins’:

Jean-Pierre Brissot, a journalist

Jean-Marie and Manon Roland

Pierre Vergniaud, member of the National Convention, famous as an orator

Jérôme Pétion

François-Léonard Buzot

Jean-Baptiste Louvet

Charles Barbaroux, a lawyer from Marseille and many others

Albertine Marat, Marat’s sister

Simone Evrard, Marat’s common-law wife

Defermon, a deputy, sometime President of the National Convention

Jean-François Lacroix, a moderate deputy: goes ‘on mission’ to Belgium with Danton in 1792 and 1793

David, a painter

Charlotte Corday, an assassin

Claude Dupin, a young bureaucrat who proposes marriage to Louise Gély, Danton’s neighbour

Souberbielle, Robespierre’s doctor

Renaudin, a violin-maker, prone to violence

Father Kéravenen, an outlaw priest

Chauveau-Lagarde, a lawyer: defence council for Marie-Antoinette

Philippe Lebas, a left-wing deputy: later a member of the Committee of General Security, or Police Committee; marries Babette Duplay

Vadier, known as ‘the Inquisitor’, a member of the Police Committee

Implicated in the East India Company fraud:

Chabot, a deputy, ex-Capuchin friar

Julien, a deputy, former Protestant pastor

Proli, secretary to Hérault de Séchelles, and said to be an Austrian spy

Emmanuel Dobruska and Siegmund Gotleb, known as Emmanuel and Junius Frei: speculators

Guzman, a minor politician, Spanish-born

Diedrichsen, a Danish ‘businessman’

Abbé d’Espanac, a crooked army contractor

| BasireDelaunay |  | deputies |

Citizen de Sade, a writer, formerly a marquis

Pierre Philippeaux, a deputy: writes a pamphlet against the government during the Terror

Some members of the Committee of Public Safety:

Saint-André

Barère

Couthon, a paraplegic, a friend of Robespierre

Robert Lindet, a lawyer from Normandy, a friend of Danton

Etienne Panis, a left-wing deputy, a friend of Danton

At the trial of the Dantonists:

Hermann (once of Arras), President of the Revolutionary

Tribunal

Dumas, his deputy

Fouquier-Tinville, now Public Prosecutor

| FleuriotLiendon |  | prosecution lawyers |

Fabricius Pâris, Clerk of the Court

Laflotte, a prison informer

Henri Sanson, public executioner

Map of Revolutionary Paris

PART ONE

LOUIS XV is named the Well-Beloved. Ten years pass. The same people believe the Well-Beloved takes baths of human blood … Avoiding Paris, ever shut up at Versailles, he finds even there too many people, too much daylight. He wants a shadowy retreat …

In a year of scarcity (they were not uncommon then) he was hunting as usual in the Forest of Sénart. He met a peasant carrying a bier and inquired, ‘Whither he was conveying it?’ ‘To such a place.’ ‘For a man or a woman?’ ‘A man.’ ‘What did he die of?’ ‘Hunger.’

Jules Michelet