Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «Every Day Is Mother’s Day»

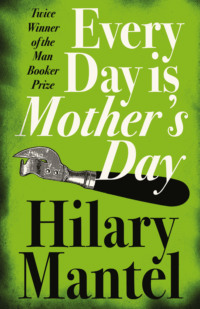

Every Day is Mother’s Day

Hilary Mantel

to the Bevington-Levitts

Two errors; one, to take everything literally; two, to take everything spiritually.

PASCAL

Do not adultery commit; Advantage rarely comes of it.

A. H. CLOUGH

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

About the Author

Excerpt from Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel

Other Books By

Copyright

About the Publisher

CHAPTER 1

When Mrs Axon found out about her daughter’s condition, she was more surprised than sorry; which did not mean that she was not very sorry indeed. Muriel, for her part, seemed pleased. She sat with her legs splayed and her arms around herself, as if reliving the event. Her face wore an expression of daft beatitude.

It was always hard to know what would please Muriel. That winter, when the old man fell on the street and broke his hip, Muriel had personally split her sides. She was in her way a formidable character. It wasn’t often she had a good laugh.

Click, click, click, said the mock-crocs. They were Mrs Sidney’s shoes. She passed without mishap along the Avenue, over that flagstone with its wickedly raised edge where Mr Tillotson had tripped last winter and sustained his fracture; they had petitioned the council. Mrs Sidney’s good legs, the legs of a woman of twenty-five, moved like scissors down the street. Her face was white and tired, her scarlet lips spoke of an effort at gaiety. She had carried the colour over the line of her thin lips, into a curvaceous bow; she had once read in a magazine that this could be done. Of what lies between the good legs and the sagging face, better not to speak; Mrs Sidney never dwelled on her torso, she had given it up. She stopped by the house called ‘The Laburnums’, by the straggling privet hedge spattered white with bird-droppings and ravaged by amateur topiary; and tears misted over her eyes. She wore the black coat with the mink trim.

Arthur had been with her when she bought the coat. It was budgeted for; the necessity had been weighed. Arthur had been embarrassed, standing among the garment rails; he had clasped his hands behind his back like Prince Philip, and with his eyes elsewhere he tried to look like a man deep in thought. She had not trailed him around the shops, she knew what she wanted. ‘A good coat,’ she said to him, ‘a good cloth coat is worth every penny you spend on it.’

She had tried on two, and then the black. The salesgirl was sixteen. She was not interested in her job. She stood with one limp arm draped over the rail, her hip jutting out, watching Mrs Sidney push the laden hangers to and fro. She did not know anything about the cut of a good cloth coat. Mrs Sidney removed her gloves, and her fingers stroked the little mink collar appreciatively. She had tried to engage Arthur’s attention, but he was not looking, and for a second she was shot through with resentment. Carelessly she tossed her old camelhair over a rail; until this morning it had been her best coat, but now it seemed shabby and inconsiderable. She unfastened the buttons carefully, slipped her arms into the silky lining. Turning to see the back in the long mirror, she smiled tentatively at the salesgirl. ‘Do you think the length…?’

The girl raised her thin shoulders in a shrug.

By now Arthur stood smiling at her indulgently, his hands still clasped behind his back.

‘I will take it,’ Mrs Sidney said. She minced towards Arthur.

‘Very nice, dear,’ Arthur said. ‘Are you sure you’ve got what you wanted?’

She nodded, smiling. He would have been willing, she knew, to pay twenty pounds more, once he had agreed on the economy of a good cloth coat. Arthur did not stint. The girl laid it out by the cash register, flapped some tissue between its crossed arms and slid it, folded, into a big bag. Arthur took out a virgin chequebook, and his rolled-gold fountain pen. Precisely, he unscrewed the cap; smoothly, the ink flowed; with care, he replaced the cap and returned the pen to the inside pocket of his lovat sports jacket. Then, with a single neat pull, he removed the cheque and handed it courteously to the girl. Mrs Sidney was proud of that, proud of the way the transaction had been carried through; how they did not pay in greasy bundles of notes like plumbers and housepainters. The carrier bag was heavy, with the good cloth coat inside it, and Arthur reached out without speaking and took it from her. He asked about a hat, so anxious was he to have everything correct; but she told him that people do not go in so much for hats nowadays. To be truthful, millinery departments intimidated her. The assistants looked at you scornfully, for so few of the people who tried on hats ever made a purchase; they had lost faith in human nature. She was happy. They had a cup of coffee and a cream cake each, and then they went home.

That night Arthur had his first stroke. When she got up in the morning, all the right side of his body was paralysed, and his mouth was twisted down at the corner; he couldn’t speak. By eight o’clock he was lying on a high white bed at the General. She was sitting outside the ward, drinking the strong tea a nurse had given her out of a chipped white cup. All she could think was, you can get these cups as seconds on the market. Could that be where they get them? A hospital, could it be? He’s on the free list, the nurse said, you can come at any time. When she went to see him he moved restlessly those parts he could move; he never again knew what day of the week it was, or anything at all about the world in the corridor or the market-place beyond. He suffered his second stroke while she was there, and they put lilac screens around the bed and informed her that he had passed away. She wore the black coat to his funeral.

Mrs Sidney raised one elegant knee a little, to prop her bag on it, fumbled inside and took out a pink tissue. Standing by the stained and formless privet, she dabbed her eyes. She looked for a litterbin, but there were none in the Avenue. She screwed the tissue back into her handbag and scissored along the street.

The Axons’ house stood on a corner. There was a little gate let in between the rhododendrons. No weeds pushed up between the stones of the path. And this was odd, because you would not have thought of Evelyn Axon as a keen gardener. There was stained glass in the door of the porch, venous crimson and the storm-dull blue of August skies. Mrs Sidney stopped a pace from the door. She feared her nerve was going to fail her. Again she fumbled with her bag, patting for her purse to make sure it was still there. She did not know whether Mrs Axon accepted payment. A small tickle of grief and fear rose up in her throat. She arrived at her decision; Mrs Axon would already be watching from some window in the house. She placed her finger on the doorbell as if she were buttonholing the secret of the universe. It did not work.

But somewhere, in the dark interior of the house, Evelyn moved towards the door. She opened it just as Mrs Sidney raised her hand to knock. Mrs Sidney lowered her arm foolishly. Evelyn nodded.

‘Come in,’ she said. ‘I suppose you want to speak to your late husband.’

It was a nice detached property. As soon as she entered the hall behind Evelyn, Mrs Sidney’s eyes became viper-sharp. She took in the neglected parquet floor, the umbrella stand, the small table quite bare except for one potplant, withered and brown.

‘Nothing seems to survive,’ Evelyn said.

Mrs Sidney took a tighter grip on her bag.

‘And into the front parlour,’ Evelyn said.

Then she kept her eyes on Evelyn’s fawn cardigan, the bulky shape moving weightily ahead. It was a sunless room, seldom used; at this time Evelyn lived mostly at the back of the house. There were heavy curtains, a round dining-table in some dark wood, eight hard chairs with leather seats; a china cabinet, and two green armchairs placed at either side of the empty fireplace. ‘You’ll want the fire,’ Evelyn said; she was nothing if not a good hostess. Mrs Sidney took one of the armchairs, knees together, her handbag poised on them. Evelyn shuffled out and left her alone. She stared at the china cabinet, which was quite empty.

Evelyn returned with a little electric fire, two bars, dusty, the flex fraying. ‘If you don’t mind,’ Mrs Sidney said, ‘that’s dangerous. Bare wires like that.’

Evelyn slammed the plug firmly into the socket. As she stood up, she gave Mrs Sidney what Mrs Sidney called a straight look, the kind of look that is given to people who speak out of turn. ‘Make yourself comfortable, Mrs Sidney,’ she said.

Once again, Mrs Sidney was struck by the cultured tone of Evelyn’s voice. She was, had been, what old-fashioned people called a lady. She and her husband had lived in this house when these few dank autumnal avenues were the best addresses in town. The Axons had always kept to themselves. For years the neighbours had complained about Evelyn’s ways, about the odd times at which she hung out her washing, about her habit of muttering to herself in the queue at the Post Office. Yet, Mrs Sidney thought, she was a cut above. In a way she was a very tragic woman; Mrs Sidney had a nose for tragedy these days, alerted to it by her own. ‘You’ll have to excuse my not providing tea,’ Evelyn said. ‘It’s not convenient. I’m not going into the kitchen today.’ Mrs Sidney blinked. For want of reply, her eyes slid back to the empty china cabinet.

‘Smashed,’ Evelyn said. ‘All smashed years ago.’

Evelyn went over to the sideboard. It was, Mrs Sidney noted, the most modern piece of furniture in the room. It had one of those compartments for drinks, and a flap that came down to serve them on. Evelyn pulled it down. Mrs Sidney gaped. She could make out the labels from here; baked beans, salmon, ox-tongue. Evelyn reached into the back and took out a half-full bottle of orange squash. From a cupboard, she took two glasses and poured a careful measure into each. On the table stood a jug of lukewarm water. Evelyn set down one of the glasses by her guest’s side, and took the armchair opposite.

‘I expect you will want to talk about him a little,’ she said. She sat upright and alert, watching her visitor, noting how the face-powder had caked at the side of her nose, how the open pores of her cheeks shone, how the body mocked the pretty, lively legs. And suddenly Mrs Sidney crumpled, as if she had been dealt a blow; her bag slid from her knees to the floor, her shoulders sagged, great gouts of grief came dropping from her mouth. Yes, Evelyn thought, how they steer you to cheerful topics; how after twice meeting they cross the road and pretend that they didn’t see you so that they can avoid the whole embarrassing encounter: a widow. There is, Evelyn reflected, a custom known as Suttee; to judge by their behaviour, many seemed to think its suppression an unhealthy development.

She watched. Mrs Sidney’s mouth worked, and the scarlet line of lipstick above her top lip contorted independently of the mouth, so that her face seemed to be slipping in and out of some grotesque and ludicrous mask. The woman lurched forward; her hands scrabbled for her bag and she scrubbed at her face with the pink tissues and dropped them in sodden balls on the carpet and on to the chair. Evelyn reached for her orange juice and took a sip. She put down the glass carefully, on a mat with a fringe. ‘Mr Sidney was a good husband to you,’ she suggested.

Mrs Sidney talked about the buying of the coat, of the cakes they had eaten, of the vast corridors of the hospital with its draughts and swinging firedoors; the stained walls, the starched impatience of doctors’ coats and the dreadful grimace of his paralysed mouth. As she talked she gasped and retched at the memories, but in the end she calmed herself, sat upright and shaking on the edge of the chair, her legs crossed tightly and her eyes formless and red. She was ready to begin.

‘Mr Sidney’s line of work was with the Transport Authority,’ she said carefully. She spoke as if each of her words was a precious crystal glass coming out of a crate; one slip could shatter her again.

‘You mean the Bus Company?’ Evelyn said.

‘It was a kind of insurance work. When – if, you see, there was an accident, someone was in an accident on the bus, he would be finding out what happened and deciding how much the Bus – the Transport Authority – ought to pay out for it. He was called a Claims Investigation Agent.’

‘Yes,’ Evelyn said. ‘He was a clerk. I understand. Now I will tell you, Mrs Sidney, sometimes I meet with success and sometimes I don’t. If you would call it success; I would say, results. It appears that they tell some people that all is very beautiful on the ninth plane and that there are flowers and organ music, but they never said that to me, and if they do say it I think they must be confusing it with the funeral. It would be a natural mistake. On those grounds, I hardly approve of cremation.’

‘But do you ever’, Mrs Sidney hesitated, ‘do you ever speak with your own husband?’

‘Clifford died in 1946,’ Evelyn said. ‘He was a quiet man, and I suppose we have less in common than we did.’

‘What did—did he pass over suddenly?’

‘Very suddenly. Peritonitis.’

There was a silence. Mrs Sidney broke it with difficulty. ‘Do you use a wineglass?’

Evelyn snorted. ‘If you want that, you get it at parties, don’t you?’

‘I’m sorry,’ Mrs Sidney said. She stood up. ‘Mrs Axon, I’m sorry, I don’t think I should have come. If my daughter knew she’d kill me.’

‘And your curiosity would be satisfied,’ Evelyn said. ‘How old are you, Mrs Sidney?’

‘Since you ask, I’m sixty-five.’

Evelyn sighed. ‘Not a great age, but you ought to know what to expect. If I were you, I’d sit down, and we can get on.’

Mrs Sidney sat. She stared about her, hypnotised by her own temerity, by Evelyn’s watery blue eyes, by the dull sheen of the afternoon light on the hard leather chairs.

Presently Evelyn leaned forward, her hands clasped together, her eyes closed, and scalding tears dropped from under her lids. Mrs Sidney watched them falling. Her heart hammered. Evelyn’s mouth gaped open, and Mrs Sidney dug her nails into her palms, expecting Arthur’s voice to come out.

Evelyn dropped back in her chair. Her pale eyes snapped open, and she spoke in a perfectly normal voice.

‘I told you not to come to me for reassurance, Mrs Sidney. Go to the Spiritualist Church if you like. It’s in Ruskin Road. They have a cold buffet afterwards.’ She got heavily to her feet. Mrs Sidney lurched after her, past the empty china cabinet and the dead pot-plant, stumbling to the door.

‘Mrs Sidney,’ Evelyn said, ‘your husband Arthur is roasting in some unspeakable hell.’

She closed the door. I shall give this up, she thought. They come here, for a Cook’s Tour of the other world; as if it were in some other but accessible place, they use me like an aeroplane, like a cruise liner. But it was here, a little removed yet concurrent; each day some limb of the supernatural reached out to pluck you by the clothes. I shall give it up, she thought, because it is making me ill; if one day I took some sort of fit and were laid up, what would happen, who would look after Muriel?

AXON, MURIEL ALEXANDRA

DATE OF BIRTH: 4.4.40

2 Buckingham Avenue

Miss Axon was visited at her home by Miss Perkins of this Department on 3.3.73 and subsequently by CWD on 15.3.73. Client lives with her widowed mother, Mrs Evelyn Axon. Her father died in 1946. They are resident in a comfortable detached house with all usual amenities. Client attended St David’s School, Arlington Road, 1945—1955, but her attendance seems to have been nominal as her mother states she was ‘more often absent’. Mrs Axon states that she was informed about 1946 or 1947 that Muriel did not seem to have the normal aptitude for her age-group, and she was kept behind a class for two subsequent years. At this point it appears client should have been designated ESN under the provisions of the 1944 Act, but this was not done and it is suggested that at this point in time she appeared in a borderline normality situation. Mrs Axon states that she considered that client had been adversely affected by her father’s death at six years old and that ‘she would not have benefited’ from special provision. During the years following Mr Hutchinson, then School Attendance Officer, visited the house on several occasions but unfortunately these records cannot be traced in the files of the newly-constituted Education Welfare Department. (Query check County Hall.) According to Mrs Axon client was referred (by Mr Hutchinson) to the Gresham Trust which prior to the takeover of its functions by the Local Authority dealt with the welfare of the subnormal in the community. Client was visited by a caseworker of the Trust, a Miss Blackstone, and Mrs Axon states that tests were given to the client but that she refused to participate in them. Mrs Axon states that the visits of the Trust ceased after one year and there appear to be no records of client as it does not seem to have been the policy of the Trust to keep records for more than five years.

Client appears physically fit. Mrs Axon states that other than the usual childhood illnesses she has never been seriously ill, never been hospitalised, and has not had occasion to visit her GP in the last ten years or possibly more. Mrs Axon is in general very vague about dates. Mrs Axon states that Muriel is able to wash and dress herself but will ‘put on anything’ and that she has to supervise her washing and also her meals as she will eat unsuitable food. However she is able to help in the house though Mrs Axon states she is not very willing. She is sometimes taken shopping by Mrs Axon but not frequently. Mrs Axon states that client is not able to go out alone because of various incidents that have occurred in the past, but she would not go into any further details about this.

Mrs Axon is extremely uncommunicative in herself and this is seen as a problem in assessment. According to Mrs Axon client is able to understand everything that is said to her but often does not answer when she is spoken to. She has no hobbies or pastimes. Difficulties in this case are increased by the uncooperative and almost hostile attitude of Mrs Axon, who seems to resent any intervention by welfare agencies. Client’s environment seems to be unstimulating and Mrs Axon seems to be ashamed of her to the extent that she is unwilling for her to be seen by neighbours. Her attitude to her seems to be one of basic contempt and that client does not have ordinary feelings, for instance she referred to client in her hearing as a ‘hopeless idiot’. It must be said that client appears to be adequately fed and clothed and that although Mrs Axon’s standards of housekeeping are not high she does attend to client’s physical welfare, but she seems to have a negative attitude to client’s mental and emotional development and it is unlikely that any significant improvement will take place unless Muriel is encouraged to mix a little more with other people and acquire social confidence.

Recommendations: Multi-professional assessment

Day care

C. W. D.

Department of Social Services

Wilberforce House

15th April 1973

Dear Mrs Axon,

You may remember that I visited you on March 15th to discuss your daughter’s case and we agreed then that it would be helpful to Muriel if she could attend a day care centre where she would be enabled to mix with other young people and take part in group activities. I have looked into the possibility of this but unfortunately there is a waiting list for our Community Daycare Centres and I have only been able to arrange for Muriel to attend initially for one afternoon a week. However, I feel sure she will benefit from this, and we do look forward to extension of our provision in the near future. She will be able to take part in informal activities like community singing, and she will also be able to try her hand at crafts such as pottery and basket weaving. Our Community Daycare Centre is situated on Calderwell Road. Muriel will be collected by minibus from the corner of Buckingham Avenue and Lauderdale Road, and will be returned to the same point. The hours of our Daycare Session are from 1.30 p.m. to 4.30 p.m. and she should be at the collection point by 1.15 p.m. There is no charge for transport. A nominal charge of 15p is made for tea and biscuits. Her first session will be on Thursday 25th April.

Unfortunately because of pressure on our facilities I have not yet been able to arrange for Muriel to be seen by our psychologist, but I assure you that this will take place at the earliest possible opportunity.

Yours sincerely,

CATHERINE W. DAWSON

One year on; noises from above. They are hard at work again, always at work. Sometimes, as today, in one room of the house, shrieking with laughter and tossing her possessions. Or following her from room to room.

Pulling her fawn cardigan about her, Evelyn lumbered over to the calendar. Woolly lambs pranced in a meadow impossibly green, roses bloomed around the door of a thatched cottage. She searched for the month. All the Thursdays were ringed in red; it was a task she had set herself when this last bout of interference with their lives began, over a year ago now. And today was Thursday.

Now for the hallway. She flicked on the light. It seemed empty. As she moved to the foot of the stairs something grazed her sleeve, and she pulled away. Go, go, she thought savagely; I did not invite you here. A bloody handprint stained the cream emulsion, the leprous skull grinned behind glass. Mr Sidney’s twisted mouth, in another place. Never again.

She mounted the stairs heavily. Her rheumatism was worse this year, in the raw damp April weather; every day sodden petals from the flowering trees flurried across the window, and thrushes sang in the neglected garden. I am sixty-eight, she thought, I am feeling my age this year.

‘Don’t you know it’s Thursday?’ Evelyn said sharply. Muriel raised her head. She nodded. Evelyn appraised her; the lank black hair cut straight across her forehead, the coarse flaking skin, the ungainly legs and large red hands. Whatever they say, she thought, she has not improved. Whatever they say, is rubbish. ‘Well, then, we must sort you out some clothes.’

A sign of animation crossed Muriel’s face. She got up. Crossing to her chest of drawers, she proffered Evelyn her pink cardigan of fluffy wool. Evelyn nodded without interest. ‘If you like.’

Something caught her eye. She plunged her hand into the drawer and delved for the metallic glint. She held it in her palm as if it were contaminated; a tin of furniture polish, half-used, its waxy rag still stuck inside it.

‘Did you put it there?’

Muriel’s pale grey eyes gazed at her. She showed neither guilt, nor fear, nor surprise. Evelyn believed her. Muriel never did anything of her own volition; Muriel never lied.

‘They’ve been in here, then?’ She reached out to grasp Muriel’s arm above the elbow, squeezing it hard. She was a strong woman. Her fingers bit into the flesh. Muriel blinked at her. ‘Did you see them?’ She shook her daughter’s arm. ‘Tell me what they did.’

Evelyn’s pulse raced. Until now they had never been in this room. But now here was the proof of it, the tin taken some weeks ago. It was always the same kind of trick; the spilt sugar, the small thefts, the china they had smashed piece by piece. She let Muriel’s arm go and it fell limp at her side.

‘1 could move you from here. But where would you go? They are always getting into my bedroom.’

Muriel said that there was a third bedroom. Evelyn stared at her. She could feel again her heart hammering and pounding in her throat. The woman had made a shocked face when she had called Muriel an idiot. She, Evelyn, lived with the daily confirmation of her idiocy. Only a hopeless idiot would suggest she took up residence in a room already tenanted; and such tenants. ‘Wash yourself,’ she commanded her. She went downstairs.

At ten past one she called up to Muriel. Muriel came down. She wore the fluffy pink cardigan and a red skirt. She showed none of the caution Evelyn used when she moved about the house. Sitting on the step next to the bottom, Muriel put out her feet for her shoes to be laced, her legs stiff like a child’s in the dentist’s chair. There was something almost sly in Muriel’s face. But Evelyn never troubled to interpret her expressions; she could speak, if she wished, she could make herself clear.

‘If you can make baskets, why can’t you tie your shoes?’ Evelyn said brutally. Probably, she thought, the reason is that she cannot make baskets; if the other week’s example is anything to go by. She took Muriel to the door. She had only to walk fifty yards, along the bushes, around the corner to Lauderdale Road. Let her do that by herself, the Welfare woman had begged; to give her a little sense of independence. She had looked at the woman with contempt. In those days she had been very high-handed with them. She had underestimated their persistence. They had kept coming back. Now she was ready to do anything they said, to make the sacrifice of Muriel, if only it would stop them coming to the house, enquiring into the arrangements she found it necessary to make, the shifts and expedients by which she kept them washed and fed and warm from one day to the next; sniffing around with their implications that life could be improved.

She held the door open to watch Muriel out of the gate. Florence Sidney was passing, a stout, well-set-up woman. She had the house, now that her mother had been taken away to a home. It was Florence Sidney, Evelyn thought, who reported us to the Welfare. As if persons in our class of life needed the Welfare. Miss Sidney turned her bonneted head curiously, and Evelyn drew back and slammed the door. She turned to the house, alone; so often, in the 1940s, she had wished she were alone, and now her wish had come back to mock her, to gibber and tiptoe and hiss.

They had not eaten lunch. That was Muriel’s punishment for not speaking when she had been asked about the visitors to her room. Whether something she had seen had terrorised her into silence…Evelyn wondered if she had been unjust. It was too late. Still, she would have her tea and biscuits.

On the floor of the hall lay a crumpled piece of paper. Evelyn’s gorge rose. Low stinking entities, she said to herself. Once she had been able to smell them, but her senses were becoming blunter with age. Increasingly they were choosing this method of communication, this, their tricks, the sharp raps on the wall from different rooms of the house, warning her off by their noises or luring her by their silence. She stopped. Her face twisted. She tried always to avoid showing that she was in pain. It was agony for her to bend to the floor, they must know this. Evelyn looked around. She took her umbrella from the hallstand, and with it fished for the paper, dragging it from where she could not reach, like the intelligent ape in the experiment. From her feet, she scuttled the paper ball to the first stair, from there to the second. She picked it up and straightened it out. The wavering great letters were familiar by now, fly-track thin: GO NOT TO THE KITCHIN TODAY.

Evelyn’s heart sank. Like this, they prolonged her existence. They could take her at any time, kill her (broken neck at the foot of the stairs) or leave her a shell without faculties. But they preferred to watch her fear, her pathetic ruses, her flickering hopes which they would dash within the hour; that was the only explanation. Disconsolate, she entered the front parlour. There, placed precisely in the centre of the circular table, lay a tin-opener.

At once she thought, how provident. It was a matter in which she had been careless. She did not touch it, examined it with her eyes. It did not belong in the house, she had never seen it before. Carefully, she picked it up. It was new, quite new. It was the first time they had left her a gift.

She lowered the flap of the sideboard and took out a tin of baked beans. I must make better arrangements, she thought. The days when they forbade her the kitchen were becoming more frequent, they were driving her increasingly to the front parlour with its hard chairs where she had seen the dead. Perhaps, she thought, a paraffin stove. She opened the tin, and cast around. To hand came the heavy glass ashtray, unused since Clifford died. She emptied the cold tan slime into it and sat eating the beans with her fingers. When she had finished she put down the ashtray and sat resting for a moment. Now where would she go, until it was time for Muriel again? The blue light bounced off polished wood. The air was silent, serene. Evelyn breathed deeply. All their ingenuity had satisfied itself, for the afternoon. Travelling around the room searching the corners, her eye fell on the basket which Muriel had brought home two weeks ago from the Handicapped Class. It was a very ill-made basket, very mis-shapen. Evelyn could not think what use to put it to. Because she was very considerate about Muriel’s feelings, she had not discarded it. Now she took it and hobbled out with it to the hall, where she placed it on the table, for display. As an afterthought, she lifted the dead plant in its plastic pot, and placed it inside.

Tasuta katkend on lõppenud.