Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «Roaring Girls»

Copyright

HQ

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Text copyright © Holly Kyte 2019

Illustration copyright © Becky Glass 2019

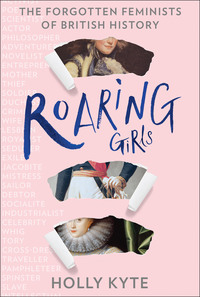

Cover images: Dorothy Jordan by John Hoppner, 1791 © National Portrait Gallery Duke of Aumale by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, 1846 © Bridgeman Images Lady Diana Cecil attrib. to William Larkin, c. 1614 © Bridgeman Images

Holly Kyte asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008266080

Ebook Edition © 2019 ISBN: 9780008266097

Version: 2019-11-21

AUTHOR’S NOTE:

Spellings, capitalisation and italicisation have been silently modernised throughout for clarity and consistency.

Dedication

For Mum and Dad, for everything.

Epigraph

roaring girl: (n) a noisy, bawdy or riotous woman or girl, especially one who takes on a masculine role

OXFORD ENGLISH DICTIONARY

COVER

TITLE PAGE

AUTHOR’S NOTE

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

EPIGRAPH

INTRODUCTION

MARY FRITH: The Roaring Girl

MARGARET CAVENDISH: Mad Madge

MARY ASTELL: Old Maid

CHARLOTTE CHARKE: En Cavalier

HANNAH SNELL: The Amazon

MARY PRINCE: Goods and Chattels

ANNE LISTER: Gentleman Jack

CAROLINE NORTON: A Painted Wanton

AFTERWORD: Unfinished Business

NOTES

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

INTRODUCTION

Girls, we’re told, are not supposed to roar. We’re supposed to shut up, be quiet, stop nagging. We’re supposed to calm down, dear. If we don’t, we’re bossy, we’re aggressive, we’re nasty, we’re bloody difficult. We’re a bunch of loud-mouthed feminazis and hysterical drama queens. If our skirts are too short, we’re asking for it, but if we don’t make an effort, we should be ashamed. If we don’t speak out, how can we expect recognition? But if we do speak out, we get trolled. And that’s in the twenty-first century, after four waves of feminism, when equality has supposedly been won.

Imagine, just for a moment, that you’re a woman in the seventeenth century. In your world, feminism doesn’t exist. You’ve been born into a rights vacuum. Your life is one long list of obligations and prohibitions. Your sole destiny as a wife and mother has been preordained since day one and the feminine ideal expected of you is to be chaste, modest, obedient – and, whenever possible, silent.

But what if you don’t want to be silent? What if you want to roar?

Mary Frith was just such a woman. A notorious cross-dressing thief in Jacobean London, she was smashing up every rule in the book when she swaggered onto the stage of the Fortune Theatre in the spring of 1611, dressed in a doublet and a pair of hose, sword in one hand, clay pipe in the other, to perform the closing number of the play she had inspired. It was called The Roaring Girl.

A Roaring Girl was loud when she should be quiet, disruptive when she should be submissive, sexual when she should be pure, ‘masculine’ when she should be ‘feminine’. She was everything a woman was not supposed to be, and in a world before feminism, she was society’s worst nightmare.[1]

A WOMAN’S LOT

The eight Roaring Girls who feature in this book lived in Britain in the 300 years before the first wave of feminists fought tooth and nail for women’s suffrage in the late 1800s, and during those centuries, the political and cultural landscape of the country changed almost beyond recognition. Collectively, these women witnessed the final wave of the English Renaissance and the last days of the Tudors. They saw their country rent by Civil War, their monarch murdered and his son restored. They found Enlightenment with the Georgian kings and experienced Empire and industrialisation in the long reign of Victoria. Britain was transforming at an astonishing rate, yet throughout this period – though it was bookended by female rule – a woman’s legal and cultural status remained virtually stagnant. She began and ended it almost as helpless as a child.

The sweeping systemic changes needed to revolutionise a woman’s rights and opportunities may have failed to materialise by the late nineteenth century, but the first rumblings of discontent had long been audible in the background. By the dawn of the seventeenth century, a radical social shift had begun to creak into action that would falteringly gather pace over the next 300 years. For although Mary Frith was the original Roaring Girl, she wasn’t the only woman of the era to find herself living in a world that didn’t suit her, and who couldn’t resist the urge to stick two fingers up at society in response; the seeds of female insurrection were beginning to germinate across Britain, and the women in this book all played their part in the rebellion.

From the privileged vantage point of the twenty-first century, it’s easy to forget just how heavily the odds were stacked against women in Britain in the centuries before the women’s rights movement, and how necessary their rebellion was. From the day she was born, a girl was automatically considered of less value than her male peers, and throughout her life she would be infantilised and objectified accordingly. Her function in the world would forever be determined by her relationship to men – first her father, then her husband, or, in their absence, her nearest male relation. On them she was legally and financially dependent, and should she end up with no male protector at all, she would find it a desperate struggle to survive.

By the age of seven a girl could be betrothed; at 12 she could be legally married. Her only presumed trajectory was to pass from maid to wife to mother and, if she was lucky, grandmother and widow. Any woman who tried to deviate from this path would quickly find her progress blocked by the towering patriarchal infrastructures in her way. Denied a formal education and barred from the universities, she would find that almost every respectable career was closed to her. She couldn’t vote, hold public office or join the armed forces. The common consensus was that her opinions were of no value and her understanding poor, and consequently she was excluded from all forms of public and intellectual life – from scholarship to Parliament to the press. While the men around her were free (if they could afford it) to stride out into the world and participate in all it had to offer, she was expected to know her place and to stay in it – suffocating in the home if she was genteel; toiling in fields, factories, homes and shops if she wasn’t. Genius was a male quality, and leadership a male occupation. Even queens would have their qualifications questioned by men who assumed they knew better.

The only ‘careers’ open to a woman during this period were those of wife and mother, but even if her homelife turned out, by chance, to be happy, these roles still came with considerable downsides. Legal impotence was perhaps the most obvious. In the eyes of the law, the day they married, a husband and wife became one person – and that person was the husband. From that moment on, the wife’s legal identity was subsumed by his.[2] Her spouse became her keeper, her lord and her master, while she, as an individual, ceased to exist. Any money she might earn, any object she might own – from her house right down to her handkerchiefs – instantly became his, while all his worldly goods he kept for himself.[3] A wife could no longer possess or bequeath property, sign a contract, sue or be sued in her own right. In principle, she was now her husband’s goods and chattels, and he could treat his new possession however he liked. If she were still in any doubt about what to expect from married life before she entered it, the Book of Common Prayer made it alarmingly clear: ‘Wives, submit yourselves unto your own husbands, as unto the Lord.’[4]

If the marriage proved miserable, even unbearable, the wife was expected to endure it. Her husband could beat her, rape her, drag her back to his home if she fled – the law would look the other way. And if he strayed from the path of righteousness into another woman’s bed, well, that was her fault, too; it could only be because she had failed to please him.

With no effective method of controlling her own fertility, successive pregnancies were often an inevitable feature of a married woman’s life, and this brought with it not only the terrors of giving birth, which, quite aside from the pain, could so easily result in her death,[5] but also the horrifying prospect that most of her children would likely not long survive. A couple during the early modern period might expect to have six or seven children born alive, but to see only two of them reach adulthood.[6]

If the marriage should break down altogether, a wife might find herself excommunicated – not just from society, but from those children, too. Like everything else, they belonged to her husband, and he could strip her of all custody and access rights with only a word. If desperate, she might try for a divorce, though if she did, she’d soon learn that she had little or no chance of ever obtaining one. Unless she was rich enough to afford a private Act of Parliament, and could prove her husband guilty of adultery and numerous other misdemeanours, including bigamy, incest and cruelty, the likelihood was all but non-existent. A husband looking to dispose of an unwanted wife, however, might have more luck – he had only to prove adultery in the lady. If all else failed, he could have her committed to the nearest lunatic asylum easily enough,[7] or perhaps drag her to the local cattle market with a rope around her neck and sell her to the highest bidder.[8]

For all these dire pitfalls, the onus weighed heavily on women to marry and have children, yet at any one time during this period an average of two-thirds of women were not married,[9] and their prospects were often even worse. The single, widowed, abandoned and separated made up this soup of undesirables, and with the notable exception of widows who had been left well provided for (they could enjoy an unusual degree of financial independence and respect), they were particularly vulnerable to hardship, poverty and ostracisation. The stigma of having failed in some way marked most of these women. And then, as now, women were not allowed to fail.

Forever held to a higher ideal, women have always had to be better. They alone were the standard bearers of sexual morality; they alone were responsible for keeping themselves and their family spotless. And since society saw no way of reconciling the fantasy of female purity with the reality of sex, it simply divided women into virgins and whores – idolised and vilified, worshipped and feared, loved and loathed. There could be no middle ground; even in marriage a woman’s sexuality had to be strictly controlled, because left unchecked it had the dizzying power to demolish social order. All it took was one indiscretion and man’s greatest fears – cuckoldry, doubtful paternity and the corruption of dynastic lineage – could come true. To avoid this chaos, women were subject to a different set of rules that were deemed as sacred as scripture: a man could philander like a priapic satyr and receive nothing worse than a knowing wink; if a woman did the same, she was ruined. Her reputation was as brittle as a dried leaf, and a careless flirtation or a helpless passion could crush it to dust. So rabid was this mania for sexual purity that it could even apply in cases of rape – so rarely brought to court and even more rarely prosecuted, though women undoubtedly endured it, and the shame, blame and suspicion that went with it.

These pernicious double standards permeated every form of social interaction between the sexes – even the very language they spoke. The nation’s vocabulary had developed in tandem with its misogyny, resulting in a litany of colourful pejorative terms designed to degrade and humiliate any woman who proved indocile. Too chatty, too complaining, too opinionated and she was a nag, a scold, a shrew, a fishwife, a harridan or a harpy. An unseemly interest in sex saw her branded a whore, wench, slut and harlot. And if she ever dared succumb to singledom or old age, she deserved the fearful monikers of old maid, crone and hag. Terms such as these were part of people’s everyday lexicon, and they have no equivalents for men.

Such thorough disenfranchisement – intellectual, economic, political, social and sexual – was the surest way to keep women contained, but despite these desperate measures, it remained a common gripe that women didn’t stick to their predetermined codes of conduct anywhere near enough. They were sexually incontinent, fickle, stupid and useless. They gossiped, carped, prattled, tattled, wittered and accused. They had even started to write books. If they would not shut up and play the game, they would have to be forced, and in these tricky cases, ostentatious methods were called for.

A nagging, henpecking or adulterous wife who had overleaped her place in the hierarchy, for example, might be ritualistically shamed in a village skimmington or charivari – in which her neighbours would parade her through the streets on horseback, serenading her with a cacophonous symphony beaten out on pots and pans, and perhaps burning her in effigy, too. Alternatively, she might be subjected to the cucking stool – an early incarnation of the more notorious ducking stool – which essentially served as a public toilet that the offending woman was forced to sit on. And there could hardly be a more sinister or more blatant symbol of the systemic gagging of women than the draconian scold’s bridle – an iron mask fitted with a bit that pinned down her tongue, sometimes with a metal spike, to quite literally stop her mouth.[10] This unofficial punishment, which was particularly prevalent during the seventeenth century, was mostly reserved for garrulous, gobby women who had spoken out of turn (or just spoken out) and challenged the authority of men, but it might also be meted out to a woman suspected of witchcraft – if she wasn’t one of the thousands who were ducked, hanged or burned for it, that is.[11]

These elaborate tortures pointed to one simple fact: that the potential power women had – be it sexual, intellectual, even supernatural – scared the living daylights out of the patriarchy. In response, it did everything it could to suppress that power and preserve its own supremacy: it kept them ignorant, incapacitated, voiceless and dependent.

By the dawn of the seventeenth century, this sorry template for gender relations had prevailed largely unchallenged for millennia. It’s a model so deeply entrenched in Western culture that it can be traced right back to the Ancients, who set the gold standard for excluding and silencing women, not only in their social and political structures but in their art and culture, too.[12] Its justification was based on one disastrously wrong-headed assumption: that women were fundamentally inferior to men. And for that we can blame both bad science and perverse theological doctrine.

Even today, we cling to the myth that men and women’s brains are somehow wired differently – an idea that modern science is rapidly disproving.[13] But in 1600, the belief that gender differences were every bit as biological as sex differences was absolute. Ever since the Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle hypothesised that women were a reproductive mistake – physically defective versions of men – it had been persistently argued in Western debate that they were mentally, morally and emotionally defective, too. It didn’t help that seventeenth-century medicine had also inherited from the Ancient Greeks the nonsense theory that the body was governed by the ‘four humours’ – blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile – which in turn were thought to be linked to the four elements: earth, fire, water and air. The belief was that a woman was comprised of cold, wet elements, while a man was hot and dry – a crucial difference that supposedly rendered her brain softer than his and her body more unstable. The catastrophic conclusion was that women had only a limited capacity for rational thought. It was no use educating them; their feeble brains couldn’t bear the strain of rigorous intellectual study. They could not be trusted to think and act for themselves, which was why they required domination. And their bodies and behaviour had to be constantly policed, because women were famously susceptible to both sexual voracity and madness – which frequently went hand in hand and were often indistinguishable.

These pernicious, ancient ideas were only reinforced by Christian doctrine. The creation myth made it abundantly clear that Eve, the first woman and mother, who had been fashioned from Adam’s rib for his comfort and pleasure, was the cause of original sin and the source of man’s woe, while early Christian writers spelled it out to the masses that it was a wife’s religious duty to bow to her husband’s authority, because ‘the head of the woman is man’[14] and to submit to him was to submit to God. By the seventeenth century, the damage had set in like rot. The message had been parroted and propagated by nearly every father, husband, preacher, politician, philosopher and pamphleteer across the land for thousands of years, until almost everyone – even women – believed it.

THE OLD RADICALS

With so many barriers in her way, so many erasures to contend with, it’s a wonder that any woman ever made it into the history books. To dismantle such deeply embedded foundations is a monumental task – so much so that we’re still working on it today. In Britain, we have at least made progress enough for this to seem an unbearable world to live in – the Gilead of our nightmares. So how did any woman cope with it? How did any woman even begin to challenge it?

The truth is, the majority didn’t even try. Browbeaten by continual put-downs and a lack of opportunity, they grimaced and bore it, most of them too poor, too ill-educated, too legally and financially dependent on men to have a means of protesting. Power and influence were not within the average woman’s grasp, and if she were anything other than white, she faced almost insurmountable odds – the lives of black and brown women in Britain are particularly absent from the historical records, though they were certainly not absent from the country.

Faced with this dead end, some women chose to take pride in their domestic roles and make the best of their lot; others were so inured to misogyny that they accepted it as normal, even became complicit in it, conned into believing that they could somehow profit from playing nicely in this twisted game.[15]

But there have always been women who refused to play by rules that had so obviously been written by men, for men. Women who couldn’t just keep quiet and carry on. Who didn’t fit the narrow criteria of what a woman ought to be, and felt instinctively that they were as valuable as any man. How did these women – the clever, the curious, the talented; those who preferred women to men, who preferred sword-fighting to child-rearing, who preferred breeches to petticoats, learning to laundry, discussion to silence, independence to marriage; who yearned for the open seas, not the scullery, and dreamed of fame, not obscurity – how did these women negotiate the hostile world around them and find the outlets they needed for all their complexities?

There was only one way: they would have to rile, unnerve, disobey and question. They would have to forfeit the title of ‘good girl’ and become a Roaring Girl instead.

This book explores how just a few of them managed it. Together, the eight Roaring Girls collected here span the full spectrum of the social hierarchy, from a duchess to a slave, and encompass a rainbow of personalities: in these pages you’ll find poets and adventurers, scientists and philosophers, actors and activists, writers and entrepreneurs, thieves and soldiers, ladies and lowlifes, wives and spinsters, mothers and mistresses, flamboyant dressers, plain dressers and cross-dressers, of every sexual preference – in short, all kinds of womanhood. Their roaring ways took various forms. Some of them used words, others action; some broke the law, others changed the law; some used their femininity, others threw it off entirely and appropriated the ways, manners and dress of men instead. All of them were playing with fire, and inevitably they sometimes got burned. For every admirer who cheered them on during their lifetimes, there were plenty more who denounced them as monsters, lunatics, freaks, devils, whores and old maids, and quickly forgot them once they were dead.

Indeed, to their contemporaries, their achievements might not have seemed particularly worth remembering. After all, they didn’t conspicuously change the world – not one of them ruled a nation, wrote a classic novel, made a pioneering discovery or led a revolution. Yet progress can come in small, surprising packages, too. That the historical records took note of these women at all suggests that they were the exceptions, not the rule, living extraordinary, not ordinary, lives, and in the pre-twentieth-century world that was quite enough to get society in a tizz. By living differently, truthfully, loudly and unashamedly, these Roaring Girls were challenging the system, and – whether they knew it or not – making a difference. The imprint they made on history may have been faint, but it’s there to be seen if we take the trouble to look. These women helped change our culture, however incrementally, and together they give a tantalising glimpse of the breadth, boldness and sheer brilliance of the legions of women who have fallen through the cracks over the centuries and tumbled headlong into the ‘Dustbin of History’.[16]