Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «You Are Not Alone: Michael, Through a Brother’s Eyes»

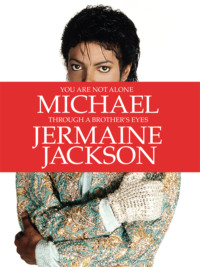

YOU ARE NOT ALONE

Michael Through a Brother’s Eyes

Jermaine Jackson

Epigraph

I have built a monument more lasting than bronze and higher than the royal palace of the Pyramids. I shall not totally die, and a great part of me will live beyond death. I will keep growing, fresh with the praise of posterity.

– Horace, 23 BC

Contents

Title Page

Epigraph

Prologue – 2005

The Beginning – The Early Years

1. Eternal Child

2. 2300 Jackson Street

3. God’s Gift

4. Just Kids With a Dream

5. Cry Freedom

6. Motown University

7. Jackson-mania

The Middle – The Hayvenhurst Years

8. Life Lessons

9. Growing Pains

10. Separate Ways

11. Moonwalking

12. Animal Kingdom

13. The Hardest Victory

14. The Reunion Party

The End – The Neverland Years

15. Once Said …

16. Forever Neverland

17. Body of Lies

18. Love, Chess and Destiny

19. Unbreakable

20. 14 White Doves

21. The Comeback King

22. Gone Too Soon

Photographic Insert

Epilogue – Smile

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

2005

THE BATHROOM MIRROR AT A LITTLE hotel in Santa Maria, California, is fogged with condensation, and there is so much steam from my morning shower that my reflection is rendered invisible. As I stand at the sink, dripping wet and wrapped in a towel, the opaque glass is now nothing but an inviting canvas of mist on which to log a thought I have been repeating in my head.

‘MICHAEL JACKSON 1,000% INNOCENT’, I daub with my finger, ending with a full-stop that I convert into a smiley-face. Believe in the happy ending.

I stare at this message and focus on a visualised outcome: victory, justice and vindication. It is 10 March 2005: day 11 of the courthouse circus that sees my brother accused of child molestation.

‘MICHAEL JACKSON 1,000% INNOCENT’, I read again. I continue to stare at the top left corner of the mirror, watching the smiley-face start to run. Transfixed, I flash back to Michael’s bathroom at the Hayvenhurst estate in Encino, outside Los Angeles – his home prior to Neverland – and know that I am mimicking in 2005 what he did in 1982. Back then, in the top left corner of his mirror, he took a black felt permanent marker – to match the black marble – and scrawled: ‘THRILLER! 100 MILLION SALES … SELL OUT STADIUMS’.

Think it, see it, believe it, make it happen. Will it into reality, as taught to us in childhood by our mother, Katherine, and father, Joseph. ‘You can do this … you can do this,’ I can hear Joseph insisting during early, scratchy rehearsals as the Jackson 5, ‘we’re doing this over and over until you get it right. Think about it, say it, see yourself doing it, visualise it happening … and it will happen.’ Plant it in your head and focus with all your heart, Mother added, more gently. This was drilled into our young minds decades before positive-thinking became fashionable. Our minds are preprogrammed not to entertain doubt or half-heartedness.

Michael knew the scale of the breakthrough, innovation and success he desired as a solo artist with the Thriller album, so that one thought transcribed on his mirror was his positive starting point. Years after his move to Neverland, the permanence of the pen’s marker had flaked and the message appeared to have disappeared to the naked eye, yet it had left its imprint embedded in the glass, because each time that mirror fogged, the faintest outline of his words could still be seen, as if it were one of those secret codes written by a magic pen. Condensation and misted glass always remind me of Michael’s written ambition.

From the eighties, nobody knew about a lot of what he created until its execution, but the idea or concept was written down somewhere he could see it daily, or recited into a voice recorder as a visualisation he could see or hear. He didn’t share ideas because he didn’t want anyone to interfere; he relied on mental strength for his focus. Between November 2003 – when he was arrested and charged – and this day in March 2005, he’s needed that strength.

Awake at 4.30am each day of the trial, he’s bracing himself, getting prepared, psyching himself up to withstand another day of ritual humiliation.

Yesterday, 9 March, Gavin Arvizo, the 15-year-old boy being showcased as ‘the victim’, began his incredulous testimony, going into graphic detail. I was seated behind Michael the whole time, as I have been since the start.

Outwardly, my brother projects a hardened image: detached, expressionless, almost cold. Inwardly, the bolted brackets that had been holding him together are snapping violently under pressure, one by one.

I look at my mirrored message now fading as the air rushes in, but the intent remains stark: Michael will be found innocent. I would carve it into my grandmother’s gravestone if I could. Think it, see it, believe it, make it happen.

But whatever intent I put out there is not enough to remove the ache and worry we feel as a family. I find myself constantly reflecting, going back to a time when we believed Hollywood to be only a magical place; when we believed in the Yellow Brick Road.

I watch the local news on the television in my room, looking ahead to day 11 of the trial. I think of Michael at Neverland. The cars will be pulling up in the courtyard. He will have been up four hours, eaten breakfast on a silver tray in his room, alone – stealing time on his own – before coming downstairs, giving himself 45 minutes between departure and arrival. His routine is clockwork, organised like some back-stage itinerary.

I think of all he has achieved, and all he is now being put through.

How has something so beautiful turned so twisted and ugly? Did fame do it? Is this the end-game in the American Dream when a black man achieves success on this magnitude? Is this what happens when an artist becomes bigger than his record label? Is this about publishing rights? Ruin the man, keep the money-machine?

These are the questions that race through my mind.

Are his Hollywood friends and one-time attorneys, allies and producers staying away because they regard him as nuclear – treating friendship like a sponsorship deal? What about those divisive people who whispered into a malleable ear that we, his family, should be kept at a distance, not trusted. Why aren’t they alongside him now, whispering encouragement and support?

Michael is fast realising who his friends aren’t, and what family means. But now his liberty is at stake, and everything he has built up is in danger of collapsing. I want to turn back time: lift the needle off the record and return us to the first track as the Jackson 5 – a time of togetherness, unity and brotherhood. ‘All for one, and one for all,’ as Mother used to say.

I play this eternal game of ‘What If?’ in my head and can’t help but think that we could have – should have – handled things differently, especially with Michael. We stood off him too much when he wanted his space and that allowed vultures into the vacuum. We allowed outsiders in. I should have done more. Stood my ground. Barged down the gates of Neverland when the people around him never let me in. I should have seen this coming and been there to protect him. I feel a dereliction of duty in the promise of brotherhood we always had.

The cell-phone rings. It’s Mother, sounding alarmed. ‘Michael is at the hospital … We’re here with him … He’s slipped and fallen. It’s his back.’

‘I’m on my way,’ I say, already out the door.

The hotel is equidistant from the Santa Maria courthouse and Neverland, and the hospital is a short detour. I’m met at a side entrance by a hospital manager to avoid any fuss out front.

On the hospital’s second-floor corridor, I see an unusual number of nurses and patients hanging around and an audible fuss dies down as I approach. A presidential-style phalanx of familiar dark-suited bodyguards is clustered around a closed door to a private room. They step aside to allow me to enter.

Inside, the curtains are drawn.

In the half-light, Michael is standing, wearing patterned blue pyjama pants and a black jacket. ‘Hi, Erms,’ he says, in almost a whisper.

‘Are you okay?’ I ask.

‘I just hurt my back.’ He forces a smile.

The fall at the ranch, when getting out of the shower, has left him in miserable pain and it appears to be the final punch at a time when life keeps pounding him. But he’s a child molester, right? He deserves this, right? The police must have some hard evidence, or he wouldn’t be on trial, right? People have a lot to learn about how wrong this trial is.

Mother and Joseph are the only other people here, sitting against the wall to my right; they are like me in not knowing what to do but be present and appear strong. Michael winces with the pain in his rib-cage and lower back, but I sense his mental pain is far greater.

In the past week, I have witnessed his physical disintegration. At 46 years old, his lean dancer’s body has withered to a fragile frame; his walk has become a pained, faltering gait; his dazzle is reduced to that forced smile; he looks gaunt, haggard.

I hate what it’s doing to him and I want it to stop. I want to scream for the scream that Michael has never had in him.

As he stands, he talks about the court testimony yesterday. ‘They are putting me through this to finish me … to turn everyone against me. It’s their plan … it’s a plan,’ he says.

Our father has never been one for deep emotional examination and, as Michael talks, I can see him itching to divert the conversation towards other plans: a concert in China.

‘Your sense of timing is not good, Joe!’ Mother tells him in admonishment.

‘What better time is there than now?’ he says. That’s Joseph. Very direct, and interpreting this time away from court as a small window to discuss something other than the trial. ‘It’ll take his mind off things,’ he adds.

It doesn’t surprise or sidetrack Michael. Like the rest of us, he’s used to it and understands that this is Joseph’s way. I interpret it as a father’s ploy to deflect his own worry about events he can’t control; to look beyond the trial to a time when Michael is free and able to perform again. Indicate light at the end of the tunnel. But it doesn’t feel like a distraction, it feels inappropriate. Anyway, my brother keeps talking. ‘What have I done but good? I don’t understand …’

I know what he’s thinking: he’s done nothing but create music to entertain and spread the message of hope, love and humanity, and awareness of how we should be with one another – especially with children – yet he is accused of harming a child. It’s akin to putting Santa Claus on trial for entering the bedrooms of children.

There is not one shred of evidence to justify this trial. The FBI knows it. The police know it. Sony knows it. (This irrefutable truth would be confirmed by an FBI statement in 2009, making it clear after my brother’s death that there was never any evidence to support any allegation in 16 years of investigations.) The authorities are just making something fit in 2005. Think it, see it, believe it, make it happen. The negative version.

Michael lifts his eyes from the floor. He looks the saddest I have ever seen him, but I can tell he just wants to talk. Up until now, he has rarely released his emotions in front of us. He has been controlled and resolute, speaking about his faith, how he trusts the judge of God, not the judge in a robe. But his controlled demeanour is now undone, no doubt triggered by yesterday’s testimony, and compounded by the frustration of this back injury.

It’s all becoming too much.

‘Everything they say about me is untrue. Why are they saying these things?’

‘Oh, baby …’ says Mother, but Michael’s hand rises. He’s still talking.

‘They’re saying all these horrible things about me. I’m this. I’m that. I’m bleaching my skin. I’m hurting kids. I would never … It’s untrue, it’s all untrue,’ he says, his voice quiet, quivering.

He starts pulling at his jacket, like an exasperated child wanting out of a costume, shifting on to both his feet, ignoring his back pain.

‘Michael …’ Mother starts.

But the tears are coming now. ‘They can accuse me and make the world think they’re so right, but they are so wrong … they are so wrong.’

Joseph is paralysed by this show of emotion. Mother’s hands are to her face. Michael pulls at his jacket buttons and starts struggling out of its sleeves. It falls off his shoulders and hangs backwards from his upper arms, revealing his bare chest.

He is sobbing. ‘Look at me! … Look at me! I’m the most misunderstood person in the world!’ He breaks down.

He stands in front of us, head bowed, as if he feels shame. It is the first time I have seen the true extent of his skin condition and it shocks me. His self-consciousness is such that he has kept his body hidden from even his family until now. His torso is light brown, splashed with vast areas and blotches of white, spreading across his upper chest; one patch of white covers his ribs and stomach, another runs down his side, and blotches cover one shoulder and upper arm. There is more white than brown, his natural skin colour: he looks like a white man splashed with coffee. This is the skin condition – the vitiligo – that a cynical world says he doesn’t have, preferring to believe that he bleaches his skin.

‘I’ve tried to inspire … I’ve tried to teach …’ and his voice trails off as Mother goes to comfort him.

‘God knows the truth. God knows the truth,’ she keeps repeating.

We all surround him, unable to hug him tight due to his back, but it is comfort nonetheless. I help put his jacket back on. ‘Just be strong, Michael,’ I said. ‘Everything’s going to be all right.’

It doesn’t take him long to compose himself and he apologises. ‘I’m strong. I’m okay,’ he says.

I leave him with my parents, vowing to return to the trial after a visit overseas. The brothers are taking it in shifts to provide support and I’ll be back in a few days.

After I leave, the bodyguards convey a message relayed from his attorney, Tom Mesereau, at the courthouse. The judge is not happy that Michael is late, and if he’s not in court within the hour, his bail will be revoked. Even his genuine pain is not honoured or believed.

At the hotel, I finish packing and watch my brother’s delayed arrival at court on television. Shielded by an umbrella to protect his skin from the sun, he shuffles along just as I left him: in his pyjama bottoms and black jacket, now wearing a white undershirt. Joseph and a bodyguard stand either side, holding him steady.

Michael had always wanted to appear pristine and dignified for his trial, choosing his wardrobe carefully. To enter like this, in his pyjamas, will be making him cringe inwardly. This whole circus seems to be careening out of control … and we are only ten days in.

I grab the hotel phone and make a call. The person on the other end of the line provides the reassurance that I needed to hear one more time: Yes, the private jet is still available. Yes, it can be at Van Nuys airport. Yes, everything has been arranged. Yes, we are ready to go whenever you are. All that is required is a day’s notice, and this DC-8 with four engines will have Michael up in the air and heading east – to Bahrain – to start a new life away from the scam of American justice. After this charade, I’m happy to disown my citizenship and take Michael, and his family, to a place where they can’t touch him. We have the backer – a dear friend. We have the pilot. Everything is prepared. There is no way my brother – an innocent man – is going to jail for this. He wouldn’t survive, and I cannot sit back and even contemplate the possibility, let alone the reality.

We’ve arranged ‘Plan B’ without his knowledge, but when I had told him not to worry because every scenario is covered, he will have suspected something, without wishing to know. He doesn’t need to. Not yet.

I have negotiated with myself that the moment Tom Meserau starts to suggest that the scales of justice are tilting against us, I will action the plan and move him to the airport in the San Fernando Valley, outside L.A. We’ll sneak him out of Neverland under a blanket, during the night. Or something. In the meantime, I resolve to play it hour by hour because, so far, Tom has said nothing other than ‘yes, that was a good day for us’, even when the testimony sounded horrible. He knows the evidential nuances, and when the prosecution is swinging with its punches and missing. We’ve quickly learned not to judge the trial by its truncated media coverage. So, I bide my time, but this trust takes all my power and has me writing messages on bathroom mirrors.

As I hit the road and drive south on auto-pilot, I start to wonder where Michael resources the strength and belief that is pulling him through this. I feel immense pride in him – at a time when he is presumed guilty until proven innocent by a media coverage that is unbalanced. It trumpets the weird and titillating testimony, leaving valid defence points as a postscript. I remember what Michael said at the start of these proceedings in 2003: ‘Lies run in sprints, but the truth runs in marathons … and the truth will win.’ The truest lyric he never sang.

I start to visualise him walking free from the criminal court. I picture it like a scene in a movie. When this is over, I will do everything I can to clear his name in the public arena. The worst will be behind us. There will be nothing else they can throw at him. And I will defend him because I know what makes him tick – his heart, his soul, his spirit, his purpose. I know the boy inside the superstar’s costume. I know the brother from 2300 Jackson Street. We have been in sync since infancy, throughout everything: the dream, the Jackson 5, the fame, the separate paths, the rifts, the sorrows, the scandals, and the impossible pressure. He has cried with me. I have shouted in his face. He has refused to see me. He has begged me to be with him. We have known each other’s loyalty and each other’s unintended betrayal. And it is because of everything contained within this history – this brotherhood – that I know his character and mind like only true blood can.

One day, I tell myself – when 2005 is behind us – people will give him a break and attempt understanding, not judgement. They’ll treat him with the same gentleness and compassion he extended to everyone else. They’ll cast aside their preconceived ideas and view him not just through his music but as a human being: imperfect, complex, fallible. Someone very different from his external image.

One day, the truth will win the marathon …

THE BEGINNING

THE EARLY YEARS

CHAPTER ONE

Eternal Child

MICHAEL WAS STANDING BESIDE ME – I was about eight, he was barely four – with his elbows on the sill and his chin resting in his hands. We were looking into the dark from our bedroom window as the snow fell on Christmas Eve, leaving us both in awe. It was coming down so thick and fast that our neighbourhood seemed beneath some heavenly pillow fight, each floating feather captured in the clear haze of one streetlight. The three homes opposite were bedecked in mostly multicoloured bulbs, but one particular family, the Whites, had decorated their whole place with clear lights, complete with a Santa on the lawn and glowing-nosed reindeers. They had white lights trimming the roof, lining the pathway and festooned in the windows, blinking on and off, framing the fullest tree we had seen.

We observed all this from inside a home with no tree, no lights, no nothing. Our tiny house, on the corner of Jackson Street with 23rd Avenue, was the only one without decoration. We felt it was the only one in Gary, Indiana, but Mother assured us that, no, there were other homes and other Jehovah’s Witnesses who did not celebrate Christmas, like Mrs Macon’s family two streets up. But that knowledge did nothing to clear our confusion: we could see something that made us feel good, yet we were told it wasn’t good for us. Christmas wasn’t God’s will: it was commercialism. In the run-up to 25 December we felt as if we were witnessing an event to which we were not invited, and yet we still felt its forbidden spirit.

At our window, we viewed everything from a cold, grey world, looking into a shop where everything was alive, vibrant and sparkling with colour; where children played in the street with their new toys, rode new bikes or pulled new sleds in the snow. We could only imagine what it was to know the joy we saw on their faces. Michael and I played our own game at that window: pick a snowflake under the streetlight, track its descent and see which one was the first to ‘stick’. We observed the flakes tumble, separated in the air, united on the ground, dissolved into one. That night we must have watched and counted dozens of them before we fell quiet.

Michael looked sad – and I can see myself now, looking down on him from an eight-year-old’s height, feeling that same sadness. Then he started to sing:

‘Jingle bells, jingle bells, jingle all the way

Oh what fun it is to ride,

On a one-horse open sleigh …’

It is my first memory of hearing his voice, an angelic sound. He sang softly so that Mother wouldn’t hear. I joined in and we started making harmony. We sang verses of ‘Silent Night’ and ‘Little Drummer Boy’. Two boys carol-singing on the doorstep of our exclusion, songs we’d heard at school, not knowing that singing would be our profession.

As we sang, the grin on Michael’s face was pure joy because we had stolen a piece of magic. We were happy briefly. But then we stopped, because this temporary sensation only reminded us that we were pretending to participate and the next morning would be like any other. I’ve read many times that Michael did not like Christmas, based on our family’s lack of celebration. This was not true. It had not been true since that moment as a four-year-old when he said, staring at the Whites’ house: ‘When I’m older, I’ll have lights. Lots of lights. It will be Christmas every day.’

‘GO FASTER! GO FASTER!’ MICHAEL SHRIEKED, hitting an early high note. He was sitting tucked up in the front of a shopping cart – knees to chin – while Tito, Marlon and I were running and pushing it down 23rd Avenue, me with both hands on the handlebar, and my two brothers either side as the wheels wobbled and bounced off the road on a summer’s day. We built up speed and powered forward like a bobsleigh team. Except this, in our minds, was a train. We’d find two, sometimes three, shopping carts from the nearby Giants supermarket and couple them together. Giants was about three blocks away, located across the sports field at the back of our home, but its carts were often abandoned and strewn about the streets, so they were easy to commandeer. Michael was ‘the driver’.

He was mad about Lionel toy trains – small, but weighty model steam engines and locomotives, packaged in orange boxes. Whenever Mother took us shopping for clothes at the Salvation Army, he always darted upstairs to the toy section to see if anyone had donated a second-hand Lionel train set. So, in his imagination, our shopping carts became two or three carriages, and 23rd Avenue was the straight section of track. It was a train that went too fast to pick up other passengers, thundering along, as Michael provided the sound effects. We hit the buffers when 23rd Avenue ran into a dead-end, about 50 yards from the back of our house.

If Michael wasn’t on the street playing trains, he was on the carpet in our shared bedroom with his prized Lionel engine. Our parents couldn’t afford to buy him a new one, or invest in an electric-train set, complete with full length track, station, and signal boxes. That is why the dream of owning a train set was in his head long before the dream of performing.

SPEED. I’M CONVINCED OUR EXCITEMENT AS kids was built on the thrill of speed. Whatever we did involved going faster, trying to outgun one another. Had our father known the extent of our thirst for speed, he would have banned it for sure: the potential for injury was always considered a grave risk to our career.

Once we grew bored of the shopping-cart trains, we built ‘go-karts’, constructed from boxes, stroller wheels and planks of wood from a nearby junkyard. Tito was the ‘engineer’ of the brotherhood and he had the know-how in putting everything together. He was forever dismantling clocks and radios, and re-assembling them on the kitchen table, or watching Joseph under the hood of his Buick parked at the side of the house, so he knew where our father’s tool box was. We hammered together three planks to form an I-shaped chassis and axle. We nailed the open cockpit – a square wooden box – on top, and took cord from a clothes line for our steering mechanism, looping it through the front wheels, held like reins. In truth, our turning circle was about as tight as an oil tanker’s, so we only ever travelled in straight lines.

The wide open alleyway at the back of our house – with a row of grassy backyards on one side and a chain-link fence on the other – was our race-track, and it was all about the ‘race’. We often patched together two go-karts, with Tito pushing Marlon, and me pushing Michael in a 50-yard dash. There was always that sense of competition between us: who could go faster, who would be the winner.

‘Go, go, go, GO!’ yelled Michael, leaning forward, urging us into the lead. Marlon hated losing, too, so Michael always had fierce competition. Marlon was the boy who never understood why he couldn’t out-run his own shadow. I can picture him now: sprinting through the street, looking down to his side, with a fierce determination on his face that turned to exasperation when he couldn’t put space between himself and his clinging shadow.

We pushed those go-karts until the metal brackets were scraping along the street, and the wheels buckled or fell off, with Michael tipped up on his side and me laughing so hard I couldn’t stand.

The merry-go-round in the local school field was another thrill-ride. Crouch down in the centre of its metal base, hold on tight to the iron stanchions, and get the brothers to spin it as fast as they could. ‘Faster! Faster! Faster!’ Michael squealed, eyes tight shut, giggling hard. He used to straddle the stanchions, like he was on a horse, going round and round and round. Eyes closed. Wind in the face.

We all dreamed of riding the train, racing the go-karts and spinning on a proper carousel at Disney.

WE KNEW MR LONG WAY BEFORE we had heard of Roald Dahl. To us, he was the original African-American Willy Wonka; this magical man – white hair, wizened features, leathery dark skin – dished out candy from his house the next avenue up, on 22nd, en route to our elementary school at the far end of Jackson Street.

Many kids beat a path to Mr Long’s door because his younger brother went to our school. Knowing Timothy meant we got a good deal, two to five cents being good value for a little brown bag full of liquorice, shoe strings, Lemonheads, Banana Splits – you name it, he had them all neatly spread out on a single bed in a front room. Mr Long didn’t smile or say very much, but we looked forward to seeing him on school mornings. We grasped at our orders and he dutifully filled the bags. Michael loved candy and that morning ritual brightened the start of each day. How we got the money is a whole other story that I will reserve for later.

We each protected our brown paper bags of candy like gold and back at the house, inside our bedroom, we all had different hiding places which each brother would try and figure out. My hide-out was under the bed or mattress, and I always got busted, but Michael squirreled his away somewhere good because we never did find it. As adults, whenever I reminded him of this, he chuckled at the memory. That is how Michael laughed throughout his life: a mesh-up of a chuckle, a snicker, a giggle; always shy, often self-conscious. Michael loved playing shop: he’d create his counter by laying a board across a pile of books, then a tablecloth, and then he’d spread out his candy. This ‘shop’ was set up in the doorway to our bedroom, or on the lowest bunk-bed, with him kneeling behind, awaiting orders. We traded with each other, swapping or using change kept from Mr Long, or from a nickel found in the street.

But Michael was destined to be an entertainer, not a savvy businessman. That seemed obvious when our father challenged him about getting home late from school one afternoon. ‘Where were you?’ asked Joseph.

‘I went to get some candy,’ said Michael.

‘How much you pay for it?’

‘Five cents.’

‘How much you going to re-sell it for?’

‘Five cents.’

Joseph clipped him around the head. ‘You don’t re-sell something for the same price you bought it!’

Typical Michael: always too fair, never ruthless enough. ‘Why can’t I give it for five cents?’ he said, in the bedroom. The logic was lost on him and he was upset over the undeserved whack on the head. I left him on the bed, muttering under his breath as he sorted his candy into piles, no doubt still playing shop in his head.

Days later, Joseph found him in the backyard, giving out candy from across the chain-link fence to other kids from the street. The kids who were less fortunate than us – and he was mobbed. ‘How much you sell ’em for?’ Joseph asked.

‘I didn’t. I gave them away for free.’

EIGHTEEN HUNDRED MILES AWAY, AND MORE than 20 years later, I visited Michael at his ranch, Neverland Valley, in the Santa Ynez region of California. He had spent time and money turning his vast acres into a theme park and the family went to check out his completed world. Neverland has always been portrayed as the outlandish creation of ‘a wild imagination’ with the suggestion that a love of Disney was its sole inspiration. Elements of this may be correct, but the truth runs much deeper, and this was something I knew immediately when I saw with my own eyes what he had built.