Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «The Girl Who Saved the King of Sweden»

COPYRIGHT

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate in 2014

First published in the United States by Ecco in 2014

Originally published in Sweden as Analfabeten som kunde räkna by Piratforlaget in 2013

Copyright © Jonas Jonasson 2014

Jonas Jonasson asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this work

‘Tonight I Can Write’, from Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair by Pablo Neruda, translated by W. S. Merwin, translation copyright © 1969 by W. S. Merwin; used by permission of Jonathan Cape, an imprint of Random House. Pooh’s Little Instruction Book inspired by A. A. Milne © 1995 the Trustees of the Pooh Properties, original text and compilation of illustrations; used by permission of Egmont UK Ltd, and by permission of Curtis Brown Ltd. How to Cure a Fanatic by Amos Oz; used by permission of Vintage, a division of Random House.

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

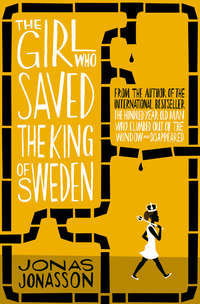

Cover by Jonathan Pelham

Source ISBN: 9780007557905

Ebook Edition © April 2014 ISBN: 9780007557882

Version: 2018-06-18

EPIGRAPH

The statistical probability that an illiterate in 1970s Soweto will grow up and one day find herself confined in a potato truck with the Swedish king and prime minister is 1 in 45,766,212,810.

According to the calculations of the aforementioned illiterate herself.

PART ONE

The difference between stupidity and genius is that genius has its limits.

Unknown

CHAPTER 1

On a girl in a shack and the man who posthumously helped her escape it

In some ways they were lucky, the latrine emptiers in South Africa’s largest shantytown. After all, they had both a job and a roof over their heads.

On the other hand, from a statistical perspective they had no future. Most of them would die young of tuberculosis, pneumonia, diarrhoea, pills, alcohol or a combination of these. One or two of them might get to experience his fiftieth birthday. The manager of one of the latrine offices in Soweto was one example. But he was both sickly and worn-out. He’d started washing down far too many painkillers with far too many beers, far too early in the day. As a result, he happened to lash out at a representative of the City of Johannesburg Sanitation Department who had been dispatched to the office. A Kaffir who didn’t know his place. The incident was reported all the way up to the unit director in Johannesburg, who announced the next day, during the morning coffee break with his colleagues, that it was time to replace the illiterate in Sector B.

Incidentally it was an unusually pleasant morning coffee break. Cake was served to welcome a new sanitation assistant. His name was Piet du Toit, he was twenty-three years old, and this was his first job out of college.

The new employee would be the one to take on the Soweto problem, because this was how things were in the City of Johannesburg. He was given the illiterates, as if to be toughened up for the job.

No one knew whether all of the latrine emptiers in Soweto really were illiterate, but that’s what they were called anyway. In any case, none of them had gone to school. And they all lived in shacks. And had a terribly difficult time understanding what one told them.

* * *

Piet du Toit felt ill at ease. This was his first visit to the savages. His father, the art dealer, had sent a bodyguard along to be on the safe side.

The twenty-three-year-old stepped into the latrine office and couldn’t help immediately complaining about the smell. There, on the other side of the desk, sat the latrine manager, the one who was about to be dismissed. And next to him was a little girl who, to the assistant’s surprise, opened her mouth and replied that this was indeed an unfortunate quality of shit – it smelled.

Piet du Toit wondered for a moment if the girl was making fun of him, but that couldn’t be the case.

He let it go. Instead he told the latrine manager that he could no longer keep his job because of a decision higher up, but that he could expect three months of pay if, in return, he picked out the same number of candidates for the position that had just become vacant.

‘Can I go back to my job as a permanent latrine emptier and earn a little money that way?’ the just-dismissed manager wondered.

‘No,’ said Piet du Toit. ‘You can’t.’

One week later, Assistant du Toit and his bodyguard were back. The dismissed manager was sitting behind his desk, for what one might presume was the last time. Next to him stood the same girl as before.

‘Where are your three candidates?’ said the assistant.

The dismissed apologized: two of them could not be present. One had had his throat slit in a knife fight the previous evening. Where number two was, he couldn’t say. It was possible he’d had a relapse.

Piet du Toit didn’t want to know what kind of relapse it might be. But he did want to leave.

‘So who is your third candidate, then?’ he said angrily.

‘Why, it’s the girl here beside me, of course. She’s been helping me with all kinds of things for a few years now. I must say, she’s a clever one.’

‘For God’s sake, I can’t very well have a twelve-year-old latrine manager, can I?’ said Piet du Toit.

‘Fourteen,’ said the girl. ‘And I have nine years’ experience.’

The stench was oppressive. Piet du Toit was afraid it would cling to his suit.

‘Have you started using drugs yet?’ he said.

‘No,’ said the girl.

‘Are you pregnant?’

‘No,’ said the girl.

The assistant didn’t say anything for a few seconds. He really didn’t want to come back here more often than was necessary.

‘What is your name?’ he said.

‘Nombeko,’ said the girl.

‘Nombeko what?’

‘Mayeki, I think.’

Good Lord, they didn’t even know their own names.

‘Then I suppose you’ve got the job, if you can stay sober,’ said the assistant.

‘I can,’ said the girl.

‘Good.’

Then the assistant turned to the dismissed manager.

‘We said three months’ pay for three candidates. So, one month for one candidate. Minus one month because you couldn’t manage to find anything other than a twelve-year-old.’

‘Fourteen,’ said the girl.

Piet du Toit didn’t say goodbye when he left. With his bodyguard two steps behind him.

The girl who had just become her own boss’s boss thanked him for his help and said that he was immediately reinstated as her right-hand man.

‘But what about Piet du Toit?’ said her former boss.

‘We’ll just change your name – I’m sure the assistant can’t tell one black from the next.’

Said the fourteen-year-old who looked twelve.

* * *

The newly appointed manager of latrine emptying in Soweto’s Sector B had never had the chance to go to school. This was because her mother had had other priorities, but also because the girl had been born in South Africa, of all countries; furthermore, she was born in the early 1960s, when the political leaders were of the opinion that children like Nombeko didn’t count. The prime minister at the time made a name for himself by asking rhetorically why the blacks should go to school when they weren’t good for anything but carrying wood and water.

In principle he was wrong, because Nombeko carried shit, not wood or water. Yet there was no reason to believe that the tiny girl would grow up to socialize with kings and presidents. Or to strike fear into nations. Or to influence the development of the world in general.

If, that is, she hadn’t been the person she was.

But, of course, she was.

Among many other things, she was a hardworking child. Even as a five-year-old she carried latrine barrels as big as she was. By emptying the latrine barrels, she earned exactly the amount of money her mother needed in order to ask her daughter to buy a bottle of thinner each day. Her mother took the bottle with a ‘Thank you, dear girl,’ unscrewed the lid, and began to dull the never-ending pain that came with the inability to give oneself or one’s child a future. Nombeko’s dad hadn’t been in the vicinity of his daughter since twenty minutes after the fertilization.

As Nombeko got older, she was able to empty more latrine barrels each day, and the money was enough to buy more than just thinner. Thus her mum could supplement the solvent with pills and booze. But the girl, who realized that things couldn’t go on like this, told her mother that she had to choose between giving up or dying.

Her mum nodded in understanding.

The funeral was well attended. At the time, there were plenty of people in Soweto who devoted themselves primarily to two things: slowly killing themselves and saying a final farewell to those who had just succeeded in that endeavour. Nombeko’s mum died when the girl was ten years old, and, as mentioned earlier, there was no dad available. The girl considered taking over where her mum had left off: chemically building herself a permanent shield against reality. But when she received her first pay cheque after her mother’s death, she decided to buy something to eat instead. And when her hunger was alleviated, she looked around and said, ‘What am I doing here?’

At the same time, she realized that she didn’t have any immediate alternatives. Ten-year-old illiterates were not the prime candidates on the South African job market. Or the secondary ones, either. And in this part of Soweto there was no job market at all, or all that many employable people, for that matter.

But defecation generally happens even for the most wretched people on our Earth, so Nombeko had one way to earn a little money. And once her mother was dead and buried, she could keep her salary for her own use.

To kill time while she was lugging barrels, she had started counting them when she was five: ‘One, two, three, four, five…’

As she grew older, she made these exercises harder so they would continue to be challenging: ‘Fifteen barrels times three trips times seven people carrying, with another one who sits there doing nothing because he’s too drunk… is… three hundred and fifteen.’

Nombeko’s mother hadn’t noticed much around her besides her bottle of thinner, but she did discover that her daughter could add and subtract. So during her last year of life she had started calling upon her each time a delivery of tablets of various colours and strengths was to be divided among the shacks. A bottle of thinner is just a bottle of thinner. But when pills of 50, 100, 250 and 500 milligrams must be distributed according to desire and financial ability, it’s important to be able to tell the difference between the four kinds of arithmetic. And the ten-year-old could. Very much so.

She might happen, for example, to be in the vicinity of her immediate boss while he was struggling to compile the monthly weight and amount report.

‘So, ninety-five times ninety-two,’ her boss mumbled. ‘Where’s the calculator?’

‘Eight thousand seven hundred and forty,’ Nombeko said.

‘Help me look for it instead, little girl.’

‘Eight thousand seven hundred and forty,’ Nombeko said again.

‘What’s that you’re saying?’

‘Ninety-five times ninety-two is eight thousand seven hund—’

‘And how do you know that?’

‘Well, I think about how ninety-five is one hundred minus five, ninety-two is one hundred minus eight. If you turn it round and subtract, it’s eighty-seven together. And five times eight is forty. Eighty-seven forty. Eight thousand seven hundred and forty.’

‘Why do you think like that?’ said the astonished manager.

‘I don’t know,’ said Nombeko. ‘Can we get back to work now?’

From that day on, she was promoted to manager’s assistant.

But in time, the illiterate who could count felt more and more frustrated because she couldn’t understand what the supreme powers in Johannesburg wrote in all the decrees that landed on the manager’s desk. The manager himself had a hard time with the words. He stumbled his way through every Afrikaans text, simultaneously flipping through an English dictionary so that the unintelligible letters were at least presented to him in a language he could understand.

‘What do they want this time?’ Nombeko might ask.

‘For us to fill the sacks better,’ said the manager. ‘I think. Or that they’re planning to shut down one of the sanitation stations. It’s a bit unclear.’

The manager sighed. His assistant couldn’t help him. So she sighed, too.

But then a lucky thing happened: thirteen-year-old Nombeko was accosted by a smarmy man in the showers of the latrine emptiers’ changing room. The smarmy man hadn’t got very far before the girl got him to change his mind by planting a pair of scissors in his thigh.

The next day she tracked down the man on the other side of the row of latrines in Sector B. He was sitting in a camping chair with a bandage round his thigh, outside his green-painted shack. In his lap he had… books?

‘What do you want?’ he said.

‘I believe I left my scissors in your thigh yesterday, Uncle, and now I’d like them back.’

‘I threw them away,’ the man said.

‘Then you owe me some scissors,’ said the girl. ‘How come you can read?’

The smarmy man’s name was Thabo, and he was half toothless. His thigh hurt an awful lot, and he didn’t feel like having a conversation with the ill-tempered girl. On the other hand, this was the first time since he’d come to Soweto that someone seemed interested in his books. His shack was full of them, and for this reason his neighbours called him Crazy Thabo. But the girl in front of him sounded more jealous than scornful. Maybe he could use this to his advantage.

‘If you were a bit more cooperative instead of violent beyond all measure, perhaps Uncle Thabo might consider telling you. Maybe he would even teach you how to interpret letters and words. If you were a bit more cooperative, that is.’

Nombeko had no intention of being more cooperative towards the smarmy man than she had been in the shower the day before. So she replied that, as luck would have it, she had another pair of scissors in her possession, and that she would very much like to keep them rather than use them on Uncle Thabo’s other thigh. But as long as Uncle kept himself under control – and taught her to read – thigh number two would remain in good health.

Thabo didn’t quite understand. Had the girl just threatened him?

* * *

One couldn’t tell by looking at him, but Thabo was rich. He had been born under a tarpaulin in the harbour of Port Elizabeth in Eastern Cape Province. When he was six years old, the police had taken his mother and never given her back. The boy’s father thought the boy was old enough to take care of himself, even though the father had problems doing that very thing.

‘Take care of yourself’ was the sum of his father’s advice for life before he clapped his son on the shoulder and went to Durban to be shot to death in a poorly planned bank robbery.

The six-year-old lived on what he could steal in the harbour, and in the best case one could expect that he would grow up, be arrested and eventually either be locked up or shot to death like his parents.

But another long-term resident of the slums was a Spanish sailor, cook and poet who had once been thrown overboard by twelve hungry seamen who were of the opinion that they needed food, not sonnets, for lunch.

The Spaniard swam to shore and found a shack to crawl into, and since that day he had lived for poetry, his own and others’. As time went by and his eyesight grew worse and worse, he hurried to snare young Thabo, then forced him to learn the art of reading in exchange for bread. Subsequently, and for a little more bread, the boy devoted himself to reading to the old man, who had not only gone completely blind but also half senile and fed on nothing more than Pablo Neruda for breakfast, lunch and dinner.

The seamen had been right that it is not possible to live on poetry alone. For the old man starved to death and Thabo decided to inherit all his books. No one else cared, anyway.

The fact that he was literate meant that the boy could get by in the harbour with various odd jobs. At night he would read poetry or fiction – and, above all, travelogues. At the age of sixteen, he discovered the opposite sex, which discovered him in return two years later. So it wasn’t until he was eighteen that Thabo found a formula that worked. It consisted of one-third irresistible smile; one-third made-up stories about all the things he had done on his journeys across the continent, which he had thus far not undertaken other than in his imagination; and one-third flat-out lies about how eternal their love would be.

He did not achieve true success, however, until he added literature to the smiling, storytelling and lying. Among the things he inherited, he found a translation the sailor had done of Pablo Neruda’s Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair. Thabo tore out the song of despair, but he practised the twenty love poems on twenty different women in the harbour district and was able to experience temporary love nineteen times over. There would probably have been a twentieth time, too, if only that idiot Neruda hadn’t stuck in a line about ‘I no longer love her, that’s certain’ towards the end of a poem; Thabo didn’t discover this until it was too late.

A few years later, most of the neighbourhood knew what sort of person Thabo was; the possibilities for further literary experiences were slim. It didn’t help that he started telling lies about everything he had done in life that were worse than those King Leopold II had told in his day, when he had said that the natives of the Belgian Congo were doing fine even as he had the hands and feet chopped off anyone who refused to work for free.

Oh well, Thabo would get what was coming to him (as did the Belgian king, incidentally – first he lost his colony, then he wasted all his money on his favourite French-Romanian prostitute, and then he died). But first Thabo made his way out of Port Elizabeth: he went directly north and ended up in Basutoland where the women with the roundest figures were said to be.

There he found reason to stay for several years; he switched villages when the circumstances called for it, always found a job thanks to his ability to read and write, and eventually went so far as to become the chief negotiator for all the European missionaries who wanted access to the country and its uninformed citizens.

The chief of the Basotho people, His Excellence Seeiso, didn’t see the value in letting his people be Christianized, but he realized that the country needed to free itself from all the Boers in the area. When the missionaries – on Thabo’s urging – offered weapons in exchange for the right to hand out Bibles, the chief jumped at the opportunity.

And so pastors and lay missionaries streamed in to save the Basotho people from evil. They brought with them Bibles, automatic weapons and the occasional land mine.

The weapons kept the enemy at bay while the Bibles were burned by frozen mountain-dwellers. After all, they couldn’t read. When the missionaries realized this, they changed tactics and built a great number of Christian temples in a short amount of time.

Thabo took odd jobs as a pastor’s assistant and developed his own form of the laying on of hands, which he practised selectively and in secret.

Things on the romance front only went badly once. This occurred when a mountain village discovered that the only male member of the church choir had promised everlasting fidelity to at least five of the nine young girls in the choir. The English pastor there had always suspected what Thabo was up to. Because he certainly couldn’t sing.

The pastor contacted the five girls’ fathers, who decided that the suspect should be interrogated in the traditional manner. This is what would happen: Thabo would be stuck with spears from five different directions during a full moon, while sitting with his bare bottom in an anthill. While waiting for the moon to reach the correct phase, Thabo was locked in a hut over which the pastor kept constant watch, until he got sunstroke and instead went down to the river to save a hippopotamus. The pastor cautiously laid a hand on the animal’s nose and said that Jesus was prepared to—

This was as far as he got before the hippopotamus opened its mouth and bit him in half.

With the pastor-cum-jailer gone, and with the help of Pablo Neruda, Thabo managed to get the female guard to unlock the door so he could escape.

‘What about you and me?’ the prison guard called after him as he ran as fast as he could out onto the savannah.

‘I no longer love you, that’s certain,’ Thabo called back.

If one didn’t know better, one might think that Thabo was protected by God, because he encountered no lions, leopards, rhinoceroses or anything else during his twelve-mile night-time walk to the capital city, Maseru. Once there, he applied for a job as adviser to Chief Seeiso, who remembered him from before and welcomed him back. The chief was negotiating with the high-and-mighty Brits for independence, but he didn’t make any headway until Thabo joined in and said that if the gentlemen intended to keep being this stubborn, Basutoland would have to think about asking for help from Joseph Mobutu in Congo.

The Brits went stiff. Joseph Mobutu? The man who had just informed the world that he was thinking about changing his name to the All-Powerful Warrior Who, Thanks to His Endurance and Inflexible Will to Win, Goes from Victory to Victory, Leaving Fire in His Wake?

‘That’s him,’ said Thabo. ‘One of my closest friends, in fact. To save time, I call him Joe.’

The British delegation requested deliberation in camera, during which it was agreed that what the region needed was peace and quiet, not some almighty warrior who wanted to be called what he had decided he was. The Brits returned to the negotiating table and said:

‘Take the country, then.’

Basutoland became Lesotho; Chief Seeiso became King Moshoeshoe II, and Thabo became the new king’s absolute favourite person. He was treated like a member of the family and was given a bag of rough diamonds from the most important mine in the country; they were worth a fortune.

But one day he was gone. And he had an unbeatable twenty-four-hour head start before it dawned on the king that his little sister and the apple of his eye, the delicate princess Maseeiso, was pregnant.

A person who was black, filthy and by that point half toothless in 1960s South Africa could not blend into the white world by any stretch of the imagination. Therefore, after the unfortunate incident in the former Basutoland, Thabo hurried on to Soweto as soon as he had exchanged the most trifling of his diamonds at the closest jeweller’s.

There he found an unoccupied shack in Sector B. He moved in, stuffed his shoes full of money, and buried about half the diamonds in the trampled dirt floor. The other half he put in the various cavities in his mouth.

Before he began to make too many promises to as many women as possible, he painted his shack a lovely green; ladies were impressed by such things. And he bought linoleum with which to cover the floor.

The seductions were carried out in every one of Soweto’s sectors, but after a while Thabo eliminated his own sector so that between times he could sit and read outside his shack without being bothered more than was necessary.

Besides reading and seduction, he devoted himself to travelling. Here and there, all over Africa, twice a year. This brought him both life experience and new books.

But he always came back to his shack, no matter how financially independent he was. Not least because half of his fortune was one foot below the linoleum; Thabo’s lower row of teeth was still in far too good condition for all of it to fit in his mouth.

It took a few years before mutterings were heard among the shacks in Soweto. Where did that crazy man with the books get all his money from?

In order to keep the gossip from taking too firm a hold, Thabo decided to get a job. The easiest thing to do was become a latrine emptier for a few hours a week.

Almost all of his colleagues were young, alcoholic men with no futures. But there was also the occasional child. Among them was a thirteen-year-old girl who had planted scissors in Thabo’s thigh just because he had happened to choose the wrong door into the showers. Or the right door, really. The girl was what was wrong. Far too young. No curves. Nothing for Thabo, except in a pinch.

The scissors had hurt. And now she was standing there outside his shack, and she wanted him to teach her to read.

‘I would be more than happy to help you, if only I weren’t leaving on a journey tomorrow,’ said Thabo, thinking that perhaps things would go most smoothly for him if he did what he’d just claimed he was going to do.

‘Journey?’ said Nombeko, who had never been outside Soweto in all her thirteen years. ‘Where are you going?’

‘North,’ said Thabo. ‘Then we’ll see.’

* * *

While Thabo was gone, Nombeko got one year older and promoted. And she quickly made the best of her managerial position. By way of an ingenious system in which she divided her sector into zones based on demography rather than geographical size or reputation, making the deployment of outhouses more effective.

‘An improvement of thirty per cent,’ her predecessor said in praise.

‘Thirty point two,’ said Nombeko.

Supply matched demand and vice versa, and there was enough money left over in the budget for four new washing and sanitation stations.

The fourteen-year-old was fantastically verbal, considering the language used by the men in her daily life (anyone who has ever had a conversation with a latrine emptier in Soweto knows that half the words aren’t fit to print and the other half aren’t even fit to think). Her ability to formulate words and sentences was partially innate. But there was also a radio in one corner of the latrine office, and ever since she was little, Nombeko had made sure to turn it on as soon as she was in the vicinity. She always tuned in to the talk station and listened with interest, not only to what was said but also to how it was said.

The weekly show View on Africa was what first gave her the insight that there was a world outside Soweto. It wasn’t necessarily more beautiful or more promising. But it was outside Soweto.

Such as when Angola had recently received independence. The independence party PLUA had joined forces with the independence party PCA to form the independence party MPLA, which, along with the independence parties FNLA and UNITA, caused the Portuguese government to regret ever having discovered that part of the continent. A government that, incidentally, had not managed to build a single university during its four hundred years of rule.

The illiterate Nombeko couldn’t quite follow which combination of letters had done what, but in any case the result seemed to have been change, which, along with food, was Nombeko’s favourite word.

Once she happened to opine, in the presence of her colleagues, that this change thing might be something for all of them. But then they complained that their manager was talking politics. Wasn’t it enough that they had to carry shit all day? Did they have to listen to it, too?

As the manager of latrine emptying, Nombeko was forced to handle not only all of her hopeless latrine colleagues, but also Assistant Piet du Toit from the sanitation department of the City of Johannesburg. During his first visit after having appointed her, he informed her that there would under no circumstances be four new sanitation stations – there would be only one, because of serious budgetary problems. Nombeko took revenge in her own little way:

‘From one thing to the next: what do you think of the developments in Tanzania, Mr Assistant? Julius Nyerere’s socialist experiment is about to collapse, don’t you think?’

‘Tanzania?’

‘Yes, the grain shortage is probably close to a million tons by now. The question is, what would Nyerere have done if it weren’t for the International Monetary Fund? Or perhaps you consider the IMF to be a problem in and of itself, Mr Assistant?’

Said the girl who had never gone to school or been outside Soweto. To the assistant who was one of the authorities. Who had gone to a university. And who had no knowledge of the political situation in Tanzania. The assistant had been white to start with. The girl’s argument turned him as white as a ghost.

Piet du Toit felt demeaned by a fourteen-year-old illiterate. Who was now rejecting his document on the sanitation funds.

‘By the way, how did you calculate this, Mr Assistant?’ said Nombeko, who had taught herself how to read numbers. ‘Why have you multiplied the target values together?’

An illiterate who could count.

He hated her.

He hated them all.

* * *

A few months later, Thabo was back. The first thing he discovered was that the girl with the scissors had become his boss. And that she wasn’t much of a girl any more. She had started to develop curves.

This sparked an internal struggle in the half-toothless man. On the one hand, his instinct told him to trust his by now gap-ridden smile, his storytelling techniques and Pablo Neruda. On the other hand, there was the part where she was his boss. Plus his memory of the scissors.

Thabo decided to act with caution, but to get himself into position.