Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

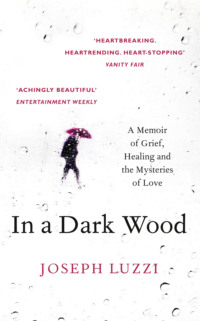

Loe raamatut: «In a Dark Wood: What Dante Taught Me About Grief, Healing, and the Mysteries of Love»

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2015

First published in the United States by Harper Wave in 2015

Copyright © Joseph Luzzi 2015

Joseph Luzzi asserts his moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

In a Dark Wood is a work of nonfiction. Some names and identifying details have been changed.

Cover design by Robin Bilardello

Cover photograph © Sheldon Serkin/EyeEm/Getty Images

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008100667

Ebook Edition © June 2015 ISBN: 9780008100643

Version: 2016-05-17

Dedication

For Isabel

l’amor che move il sole e l’altre stelle

Epigraph

Every grief story is a love story.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

I: THE UNDERWORLD

CHAPTER 1 An Hour with the Angels

CHAPTER 2 Consider Your Seed

CHAPTER 3 Love–40

II: MOUNT PURGATORY

CHAPTER 4 Astrid and Anja

CHAPTER 5 The Gears of Justice

CHAPTER 6 Rough Draft

III: ONE THOUSAND AND ONE

CHAPTER 7 Posthoc7

CHAPTER 8 Fathers and Sons

CHAPTER 9 Open Hours

Epilogue

Translations and Notes

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Joseph Luzzi

About the Publisher

Prologue

Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita, mi ritrovai per una selva oscura.

In the middle of our life’s journey, I found myself in a dark wood.”

So begins one of the most celebrated and challenging poems ever written, Dante’s Divine Comedy, a fourteen-thousand-line epic about the soul’s journey through the afterlife. The tension between the pronouns says it all: although the “I” belongs to Dante, who died in 1321, his journey is also part of “our life.” We will all find ourselves in a dark wood one day, the lines suggest.

For me that day came eight years ago, on November 29, 2007, a morning just like any other. I left my home in upstate New York at eight thirty a.m. and drove to nearby Bard College, where I am a professor of Italian. It was cold and wet, the air barely creased by the gray light. After my first class ended, I walked to my office to gather materials and then made my way to a ten thirty a.m. class.

I was joking with my students as we all settled in, when I noticed something unusual out of the corner of my eye: there was a security guard standing at the door.

“Look, they’re coming to arrest me,” I said, laughing. But the beefy security guard was not smiling.

“Are you Professor Luzzi?”

I’ve done nothing wrong, was my first thought.

“Yes—why?”

“Please come with me.”

I edged outside the classroom and saw the associate dean and vice president of the college racing up the stairwell. I started running too, down the stairs and out of the building. There was a security van waiting for me.

Joe, your wife’s had a terrible accident.

The words came from somewhere close, but they sounded muffled, as though passing through dimensions. Time and space were bending around me.

I was entering the dark wood.

EARLIER THAT MORNING AT NINE fifteen, my wife, Katherine Lynne Mester, pulled out of a gas station and into oncoming traffic, just a few miles from where I sat proctoring an exam in Italian. As close as she was, I didn’t hear the crunching blow of the oncoming van into the soft aluminum pocket of her driver’s side door, nor did I see the careening skid of her jeep as it swerved across the country highway and finally came to a full stop twenty feet from impact on the other side of the road. In the monastery-like silence of my classroom, I was unaware of the surging convoy of emergency response vehicles that were barreling up Route 9G, ready to rescue my wife from the tangle of metal and speed her to Poughkeepsie’s Saint Francis Hospital a half hour away.

These emergency responders were not just carrying my wife: Katherine was eight and a half months pregnant with our first child. Soon after the security guard had appeared at my ten thirty class, a medical team performed an emergency cesarean on an unconscious Katherine, delivering our daughter Isabel, who was limp, pale, had no respiratory effort, and whose heart rate was inaudible. The doctors applied pressure ventilation by bag and mask—but one minute into her new life Isabel’s heart rate was still slow and she had to be intubated. Slowly her heart rate rallied. Within ten minutes she was taking her first voluntary, spontaneous breaths.

Forty-five minutes after Isabel was born, Katherine died.

I had left the house at eight thirty; by noon, I was a widower and a father.

A WEEK LATER, I FOUND myself standing in the cold rain in a cemetery outside of Detroit, watching as my wife’s body was returned to the earth close to where she was born. The words for the emotions I had known until then—pain, sadness, suffering—no longer made sense, as a feeling of cosmic, paralyzing sorrow washed over me. My personal loss felt almost beside the point: a young woman who had been vibrant with life was now no more. I could feel part of me going down with Katherine’s coffin. It was the last communion I would ever have with her, and I have never felt so unbearably connected to the rhythms of the universe. But I was on forbidden ground. Like all other mortals, I would have to return to the planet earth of grief. An hour with the angels is about all we can take.

Days afterward, I went for a walk in the village where Katherine and I had been living, Tivoli, New York. By chance I ran into a neighbor who was also out walking: the chaplain who had officiated at my college’s memorial service for Katherine.

“You’re in hell,” she said to me.

I immediately thought of Dante, the author I had devoted much of my career to teaching and writing about. After a charmed youth as a leading poet and politician in Florence, Italy, the city where he was born in 1265, Dante Alighieri was sentenced to exile while on a diplomatic mission. In those first years, Dante wandered around the region of Tuscany, desperately seeking to return to his beloved city. He met with fellow exiles, plotted military action, connived with former enemies—anything to get home. But he never set foot in Florence again. His words on the experience would become a mantra to me:

You will leave behind everything you love

most dearly, and this is the arrow

the bow of exile first lets fly.

No other words could capture how I felt during the four years I struggled to find my way out of the dark wood of grief and mourning. And yet it was only because of his exile that Dante was able to write The Divine Comedy, when he accepted once and for all that he would never return to Florence. Before 1302, the year he was expelled, he had been a fine lyric poet and an impressive scholar. But he had yet to find his voice. Only in exile did he gain the heaven’s-eye view of human life, detached from all earthly allegiances, that enabled him to speak of the soul.

At the beginning of The Divine Comedy, as Dante finds himself lost in the selva oscura—the dark wood—he sees a shade in the distance. It’s his favorite writer, the Roman poet Virgil, author of The Aeneid and a pagan adrift in the Christian afterworld. By way of greeting, Dante tells Virgil that it was his lungo studio e grande amore—his long study and great love—that led him to the ancient poet. Virgil becomes Dante’s teacher on ethics, willpower, and the cyclical nature of human mortality, illustrated by his metaphor of the souls in hell bunched up like fallen leaves. Virgil is his guide through the dark wood, just as The Aeneid gave Dante the tools he needed to curb his grief over losing Florence, whose splendor would haunt him as he wandered through Italy looking for a home during the last twenty years of his life.

That’s beauty’s terrible calculus, I would come to learn: its hold over you becomes stronger after you’ve lost it.

I had met Katherine four years earlier at an art opening in Brooklyn, her tall, elegant beauty standing out amid the slouching hipsters in T-shirts and flannel. She was wearing a form-fitting dress and stood with perfectly erect posture as she drank her champagne and talked with a friend. I made a beeline for her and mustered up the courage to introduce myself. She was kind enough not to sneer at my opening line.

“Nice shoes,” I said, pointing to her spectacular leopard print heels.

“They are, aren’t they?” she answered smiling.

And with these few words my life began to flow in a new direction, one of brief but powerful happiness, the kind that changes you. The crowd buzzing around us seemed to disappear as Katherine told me about her family in suburban Detroit, the father she adored who was a federal judge and a pillar of their community. She laughed as she described her mother, a homemaker who had been raised on a cherry farm and now rankled the family with her unfiltered outbursts on subjects ranging from America’s welfare system to children who pursue artistic careers. I learned about Katherine’s fancy prep school that the family could hardly afford and that she could barely stay afloat in, and her years of fruitless auditions and demos: “My mom says stop doing freebies,” she joked. We walked through the warm October night, first in a pack, then just the two of us. I told her I was a professor, and she repeated the word slowly, looking me in the eye. I don’t know whether she was impressed or just glad to meet somebody from a staid world far from her own. By two in the morning, we were in a cab that would drop me off in Park Slope and then take her to the Upper West Side. But there was a terrible thud, and the car stopped stock-still in the middle of a Brooklyn thoroughfare.

“Sorry, man,” the driver shouted back to us, “we’ve got a flat.”

Katherine and I had fallen asleep next to each other, but now were jolted awake by the noise. Earlier in the evening, I had punched her number into my cell phone, and as we waited for the driver to fix the tire, I couldn’t help but worry that my phone could also experience a mechanical failure, just like the cab.

Later, alone in my apartment, my concern turned to panic: what if I had taken her number down incorrectly? I had no other way of contacting her, no last name, address, or mutual friends. In my southern Italian superstition, I wondered if the jolt from the flat tire was an ominous sign—that I might have lost our connection for good.

Forty-eight hours later, I dialed the number and she picked up on the first ring.

NOTHING KATHERINE AND I SHARED could prepare me for the challenges that would come when our allotted time was over. Rilke once wrote that to love another person is our ultimate task, that for which all else is preparation. Only after losing this love did I grasp his awful wisdom. One of you will have to face the world alone someday and inhabit the Underworld—the hell at the start of Dante’s descent into a dark wood.

A car accident claimed Katherine’s body, but my grief would nearly kill her memory. For the longest time after her death, she became opaque, as an unconscious force deep inside me repressed the things that we had shared. I didn’t try to distance myself from my most intense recollections of her, from the feel of her skin against my own or her smell in the morning as sleep still clung to her. Before I met Katherine I used to believe that love’s chosen space was night, the time for coupling in the dark and dreaming in tandem. But Katherine heightened the start of each day, from the first light that fell on her through the blinds beside the bed, illuminating the dust in chiaroscuro stripes, to the rhythmic weight of her breath, as heavy on my shoulders as her resting arms. Surrounded by her sleeping body, I felt love’s gravity, and it took all of my strength to disentangle myself from her and follow the streams of brightly lit dust out of the bed and into the new day. Slowly but implacably, her death began to transform these living sensations into spectral images—things that haunted my dreams and daydreams, but which I could no longer feel or smell or taste. Grief was a great disembodier.

The insulating shock that kept me from absorbing the full pain of Katherine’s loss also numbed me, preventing me from recalling the full joy of what we had shared. The love we had made, the promises we had exchanged, the plans we had scribbled on Sunday afternoon scraps of paper—grief carried them all away. Only years later, when I began to write about this lost cache of memory, would I learn that to survive Katherine’s loss I had to let her die a second time, in my thoughts and dreams, so that the pain would not paralyze me.

The day of her accident, part of my shock was tempered by the calming thought that I could speak with her later that night in spirit—after all, our relationship had been cut short almost mid-conversation. But these one-way dialogues offered only the coldest comfort; I needed a guide, someone who knew how to speak with the dead. Someone who had written about life in the dark wood.

The Divine Comedy didn’t rescue me after Katherine’s death. That fell to the support of family and friends, to my passion for teaching and writing, and above all to the gift of my daughter. Our daughter. But I would barely have made my way without Dante. In a time of soul-crunching loneliness—I was surrounded everywhere by love, but such is grief—his words helped me withstand the pain of loss.

After years of studying Dante, I finally heard his voice. At the beginning of Paradiso 25, he bares his soul:

Should it ever happen that this sacred poem,

to which both heaven and earth have set hand,

so that it has made me lean for many years,

should overcome the cruelty that bars me

from the fair sheepfold where I slept as a lamb,

an enemy to the wolves at war with it . . .

I still lived and worked and socialized in the same places and with the same people after my wife’s death. And yet I felt that her death exiled me from what had been my life. Dante’s words gave me the language to understand my own profound sense of displacement. More important, they enabled me to connect my anguished state to a work of transcendent beauty.

After Katherine died, I obsessed for the first time over whether we have a soul, a part of us that outlives our body. The miracle of The Divine Comedy is not that it answers this question, but that it inspires us to explore it, with lungo studio e grande amore, long study and great love.

This journey began for me thirty years ago in a ferocious part of Italy.

I

The Underworld

. . . BOYS AND UNWED GIRLS

AND SONS LAID ON THE PYRE BEFORE THEIR PARENTS’ EYES.

CHAPTER 1

An Hour with the Angels

La bocca sollevò dal fiero pasto.

He lifted up his mouth from the savage meal.

My uncle Giorgio recited this line to me when I was a college student visiting Italy for the first time, on my junior year abroad in Florence in 1987. A shepherd and rail worker who had never spent a day in school, Giorgio spoke neither English nor standard Italian—yet he spoke Dante. We were sitting around the table in his tiny kitchen, my ears buzzing with the dialect phrases of my childhood. Giorgio decanted glasses of his homemade wine as he welcomed me to Calabria, the region on the toe of the Italian peninsula whose la miseria—an untranslatable term meaning relentless hardship—my parents had escaped thirty years earlier when they immigrated to America.

For three days, I followed Giorgio and his son Giuseppe from one village to the next. Everyone we met—women in sackcloth, men with missing teeth—welcomed me as though I were a foreign dignitary. I never asked Giorgio how he had managed to learn some Dante by heart, and I doubt that he knew any of the actual plot of The Divine Comedy. It didn’t matter: he knew its music. Here, in the south of Italy, as far from the Renaissance splendor of Florence as you could get, he was a living and breathing trace of Dante’s presence.

Giorgio’s words stayed with me on the long train ride back to Florence, bringing me inside one of the most chilling scenes in The Divine Comedy: the one in which the traitor Ugolino lifts up his head from the man he has been condemned to cannibalize for eternity, Archbishop Ruggieri, to tell Dante how he ended up devouring his own children in the prison tower where Ruggieri had locked them. I was reading Dante for the first time, in a black Signet paperback translation by John Ciardi, while also trying to get through the original Tuscan. But nothing brought him to life like my uncle’s declaration.

Back in Florence, Dante was everywhere. Outside the Basilica of Santa Croce, a few blocks from my school, a nineteen-foot-high statue of the poet looked down sternly on the square, as though guarding the church where Machiavelli, Michelangelo, Galileo, and the nation’s founding fathers are buried. A few blocks north, the neighborhood where Dante grew up spread toward Brunelleschi’s Duomo. I had never taken a class on The Divine Comedy before my trip to Florence, but my visit to Calabria had shown me that its verses could live outside of libraries and museums and inside the huts and fields of my parents’ homeland. Dante’s simple, sober Tuscan-Italian made me feel the ground beneath me. I could smell his language.

S’ïo avessi le rime aspre e chiocce, / come si converrebbe al tristo buco . . .

“If I had verses harsh and grating enough / to describe this wretched hole,” Dante writes at the beginning of Inferno 32 to describe the depths of hell. He was as gritty and local as the Calabrian world my parents had abandoned. I plowed through the Ciardi and muddled through the Tuscan. For the first time in my life, I was inhabiting a book.

The capaciousness of The Divine Comedy—with its high poetry, dirty jokes, literary allusions, farting noises—floored me. I marveled at Dante’s universe of good and evil, love and hate, all ordered by unfaltering eleven-syllable lines in rhyming tercets. He communicated vast amounts of knowledge, medieval and ancient, without drowning out the music of his verse. He knew his Bible and his classics cold. He distilled the latest gossip about promiscuous poets, gluttonous pals, and treacherous politicians. He knew which acclaimed thirteenth-century humanist had been accused of sodomy, and he dared write about the birth of the soul and the prestige of his own Tuscan. In The Divine Comedy, I had discovered my guide, from the high culture of the Florentine cobblestones to the earthy customs of the Calabrian shepherds.

The Divine Comedy, I had come to learn, was a book of many firsts: one of the the first epic poems written in a local European language instead of Latin or Greek; the first work to speak about the Christian afterlife while paying an equal amount of attention to our life on earth; the first to elevate a woman, Beatrice, into a full-fledged guide to heaven. But these weren’t the innovations that most enthralled me—it was Dante’s groundbreaking ability to speak intimately with his readers. His twenty addresses leapt off the page and into my daydream: “O you who have sound reasoning, / consider the meaning that is hidden / beneath the veil of these strange verses,” he writes in Inferno 9. I could feel him speaking to me directly as I sat in my apartment in Piazza della Libertà, his rasping consonants and singing vowels drowning out the roar of the Vespas and the rumble of the traffic converging on the city’s nearby ring roads. I felt I could spend a lifetime exploring the mystery of his versi stani, strange verses.

Soon after my visit to Calabria, Dante’s words and his image had become, as he writes at the opening of Paradiso, a blessed kingdom stamped on my mind. I pictured him in Botticelli’s famous portrait: in regal profile, with his magnificent aquiline nose launched ahead of his piercing stare, his body swathed in a crimson cloak, and his head crowned with a black laurel, the symbol of poetic excellence given an otherworldly gravitas by the brooding color. It was a face that had been to hell and back, visited the dead and lived to tell. And it was a burning gaze that would buckle under none of life’s mysteries.

One late night in Florence I was out walking when I was arrested by a smell. I followed the scent and landed inside one of the city’s pasticcerie, pastry shops, making the next morning’s delicacies. I ordered a few brioches and took them to Santa Croce. In an empty square, I put the warm, achingly delicious pastry into my mouth as I leaned against the base of Dante’s statue. I was in Italy, I thought—not my parents’ Italy but another one, hundreds of miles from Zio Giorgio’s Calabria and light years from the mud and sorrow that my family had left behind. Dante had somehow appeared in both places.

With my mouth filled with flakes of buttery pastry, I pressed my back against Dante and stared onto the silent stones of Santa Croce.

I was falling in love.

THE DAY AFTER KATHERINE DIED, I returned to our home after spending the night in the hospital. Her morning coffee was still out by the bathroom sink, where strands of her hair lay in coils. The bed was unmade and the drawers flung open, suggesting a day open to all sorts of possibilities. She had left the apartment to attend class at a local university, where she was completing her degree after giving up on acting. We had plans to meet for dinner, and she had used my favorite coffee cup, the Deruta ceramic mug with the dragon design that I had paid too much for in Florence.

I took the sheets in my arms and breathed in her smell one last time.

My family, who had come from Rhode Island the moment they heard the news, surrounded me. Choking back sobs, my mother and sisters put on latex gloves and set out to erase Katherine’s last traces with Lysol and Formula 409.

The snow was falling outside—the first storm of the year.

Meanwhile, Isabel slept in a sterile forest of incubators in the neonatal unit of Poughkeepsie’s Vassar Brothers Hospital, its machines nourishing her after an improbable birth. They would keep her safe while I went out walking, looking for souls bunched up like fallen leaves on the shores of the dead.

The snow fell nonstop after Katherine’s accident, covering our village and announcing an early winter. The chaplain had told me I was in hell, but in my many walks around a dim, gloomy Tivoli, I felt more like I was in Virgil’s Underworld—a place of shadows, no brimstone and fire. I thought of Dante losing his “bello ovile,” “fair sheepfold.” During his lifetime, two political parties, the Guelphs and the Ghibellines, dominated Florentine politics and were perpetually at war with each other. Dante was a Guelph, which was usually pro-papacy. But in the intensely factional and family-based world of Florentine politics, a split in Dante’s party emerged, and he joined the group that resisted Pope Boniface VIII’s meddling in the city’s affairs. This infuriated Boniface, who arranged to have Dante detained while he was in Rome on a diplomatic mission in 1302. Meanwhile, back in Florence, Dante’s White Guelph party lost control of the city to the pro-papacy Black Guelphs, who falsely accused Dante of selling political favors and sentenced him to exile in absentia, ordering him to pay an exorbitant fine. Dante insisted that he was innocent and refused to pay. The Black Guelphs responded with an edict condemning Dante to permanent exile. If you come back to Florence, they warned, you will be burned alive. As I walked through the winterscape pondering Dante’s fate, fire was the last element on my mind. But I could feel the edict’s heat burn inside as the reality of my own exile descended upon me with each snowflake.

Dante would spend the first thirty-four cantos of The Divine Comedy at the degree zero of humanity, Inferno. His guide Virgil had also sung of hell in The Aeneid, of the Trojan hero Aeneas who watched Troy, sacked by the Greeks, burn to the ground, and then abandoned his lover Dido, Queen of Carthage, because the gods had decreed that he must forsake all entanglements to found Rome. At the book’s end, Aeneas confronts his defenseless enemy Turnus, who had killed his friend Pallas. “Go no further down the road of hatred,” Turnus begs him, and for a moment Aeneas relaxes the grip on his sword. But then he drives his sword into Turnus’s breast, burying the hilt in his throat—ira terribilis. Terrible in his rage.

My own grief wasn’t so ferocious. I could feel myself retreating into a cocoon, just like the one my mother made each night when she went to sleep, even in the dead of summer: the door shut, the windows sealed, the blankets pulled over her head. I wondered how she managed not to suffocate. Now I too needed total darkness. I started sleeping in the fetal position like my infant daughter.

One night I dreamed that I was back in the hospital the day of Katherine’s accident, and someone was telling me that she was alive. In critical condition, but alive. I ran out of the room and shouted to my mother and four sisters, “Is it true? Is she okay?” The adrenaline surged through me, my heart nearly exploding out of my chest.

I woke up coated in sweat, a pool of vomit welling in my stomach. It had only been a dream, not a premonition.

I became so frightened of these visions that I tried to prepare for them. Katherine is gone, Katherine is gone, I repeated to myself each night before I went to sleep, just as I had on the day she died, when I slept in a hospital room adjacent to the incubating Isabel, my mother and sister beside me. Yet the reel would not stop. One dream had Katherine and me in a car, her flesh creamy to the touch, a life-breathing pink. I asked her why she had gone, how she could do such a thing, but she just sat there in impenetrable, lunar silence. In another dream we were in a crisis, on the brink of a breakup, a situation we had never remotely approached.

I know what you’re doing, I’m saying to her, you’re trying to split up with me, for my own good, but I just can’t do it. I’m not ready. Please don’t leave me . . .

I’m begging her, just as I had begged the neurosurgeon to save her when he and his team operated on Katherine’s pummeled brain after Isabel was born.

Please, I said to him, do anything. Hook her up to a machine, I don’t care, just keep her alive!

I sat waiting in a small room in Poughkeepsie’s Saint Francis Hospital while they operated. A social worker was there beside me, along with a gray unsmiling nun who muttered something about the power of prayer. I left the room and found the hospital chapel, where I got down on my knees on a yellow polyurethane pew. A jaundiced-looking Jesus hung on a suspended cross.

Please, God. I beg you. Just keep her alive . . .

Then I made the fatal mistake of allowing myself a daydream.

“You gave us quite a scare,” I’m saying, while I hold Katherine’s hand and stroke her bruised body. But she doesn’t answer. As in the dreams that would follow, she can no longer speak.

I left the chapel. The neurosurgeon appeared in tears.

ALL YE WHO ENTER ABANDON HOPE—Dante inscribed these words on the gates of hell. But after Katherine died it wasn’t the lack of hope that was crushing me. It was the memory of what I had lost.

In 2004, Katherine and I began living together in North Carolina, where I had received a one-year fellowship at the National Humanities Center, enabling me to take a leave of absence from my regular teaching duties at Bard and focus on my scholarly research. Katherine had finally said good-bye to acting and given up her life in New York to join me in the South, as I gave up my apartment in Brooklyn with plans to move to the Bard area with Katherine after the fellowship ended. I arrived in North Carolina a few weeks before she did and set up our home while she completed a Pilates training course in New York. On the day she joined me, we went for a walk on Duke’s East Campus, the struggles of living in New York with too little money dissolving in the warm air as we walked past the colonial facades and scattered gazebos. I thought, If only we could stay here forever, extend my one-year fellowship into an eternity. I had recently turned thirty-seven, nearly the same age as Dante when he found himself in the dark wood. Unlike Dante, however, I had little to show for myself—no family of my own, no relationship where I had given of myself completely, until I met Katherine.

Tasuta katkend on lõppenud.