Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «The Sacrifice»

Copyright

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate in 2015

First published in the United States by Ecco in 2015

Copyright © The Ontario Review 2015

Joyce Carol Oates asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

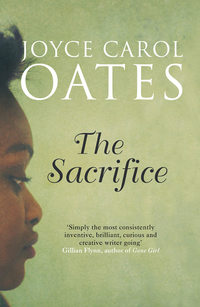

Cover photograph © Nagib El Desouky / Arcangel Images.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

Source ISBN: 9780008114862

Ebook Edition © January 2015 ISBN: 9780008114879

Version: 2015-10-13

Dedication

for Richard Levao

and for Charlie Gross

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

The Mother

The Discovery

“White Cop”

St. Anne’s Emergency

The Interview

Red Rock

“S’quest’d”

Girl-Cousins

The Investigator

Angel of Wrath

The Good Neighbor

The Lucky Man

The Stepdaughter

The Mission

The Temptation

The Seduction

The Crusade

“Nazi-Racist Swine”

“Reassigned”

The Good Son

The Twins

Safe House

“Yelow Hair”

The Prize

The Crusade

The Martyr

The Broken Doll

The Convert

The Sisters

“Still Alive”

Ten-Thousand-Man March

Afterword

Acknowledgements

Novels by Joyce Carol Oates

About the Publisher

The Mother

OCTOBER 6, 1987

PASCAYNE, NEW JERSEY

Seen my girl? My baby?

She came like a procession of voices though she was but a singular voice. She came along Camden Avenue in the Red Rock neighborhood of inner-city Pascayne, twelve tight-compressed blocks between the New Jersey Turnpike and the Passaic River. In the sinister shadow of the high-looming Pitcairn Memorial Bridge she came. Like an Old Testament mother she came seeking her lost child. On foot she came, a careening figure, clumsy with urgency, a crimson scarf tied about her head in evident haste and her clothing loose about her fleshy waistless body. On Depp, Washburn, Barnegat, and Crater streets she was variously sighted by people who recognized her face but could not have said her name as by people who knew her as Ednetta—Ednetta Frye—who was one of Anis Schutt’s women, but most of them could not have said whether Anis Schutt was living with this middle-aged woman any longer, or if he’d ever been living with her. She was sighted by strangers who knew nothing of Ednetta Frye or Anis Schutt but were brought to a dead stop by the yearning in the woman’s face, the pleading in her eyes and her low throaty quavering voice—Any of you seen my girl S’b’lla?

It was midmorning of a white-glaring overcast day smelling of the Passaic River—a sweetly chemical odor with a harsh acidity of rot beneath. It was midmorning following a night of hammering rain, everywhere on broken pavement puddles lay glittering like foil.

My girl S’b’lla—anybody seen her?

The anxious mother had photographs to show the (startled, mostly sympathetic) individuals to whom she spoke by what appeared to be purest chance: pictures of a dark-skinned girl, bright-eyed, a slight cast to her left eye, with a childish gat-toothed smile. In some of the photos the girl might have been as young as eleven or twelve, in the more recent she appeared to be about fourteen. The girl’s dark hair was thick and stiff and springy, lifting from her puckered forehead and tied with a bright-colored scarf. Her eyes were shiny-dark and thick-lashed, almond-shaped like her mother’s.

S’b’lla young for her age, and trustin—she smile at just about anybody.

In Jubilee Hair Salon, in Ruby’s Nails, in Jax Rib Joint, and the Korean grocery; in Liberty Bail & Bond, in Scully’s Pawn Shop, in Pascayne Veterans Thrift Shop, in Passaic County Family Ser vices and in the crowded cafeteria of the James J. Polk Memorial Medical Clinic as in windswept Hicks Square and several graffiti-defaced bus-stop shelters on Camden there came Ednetta Frye breathless and eager to ask if anyone had seen her daughter and to show the photographs spread in her shaky fingers like playing cards—You seen S’b’lla? Yes maybe? No?

She grasped at arms, to steady herself. She appeared dazed, disoriented. Her clothes were disheveled. The scarf tying back her stiff-oiled hair was askew. On her feet, waterstained sneakers beginning to fray at each outermost small toe with a quaint symmetry.

Since Thu’sday she been missin. Day and a night and a nother day and a night and most this time I was thinkin she be with her cousin Martine on Ninth Street comin there after school like she do sometimes and she forgot to call me, so I—I was just thinkin—that’s where she was. But now they sayin she ain’t there and at her school they sayin she never showed up Thu’sday and there be other times she’d cut since September when the school started that wasn’t known to me and now don’t nobody seem to know where my baby is. Anybody see S’b’lla, please call me—Ednetta Frye. My telephone is …

Her beautiful eyes mute with suffering and veined with broken capillaries. Her skin the dark-warm-burnished hue of mahogany. There was an oily sheen to her face, that glared in the whitely overcast air. From a short distance Ednetta appeared heavyset with large drooping breasts like water-sacks, wide hips and thighs, yet she wasn’t fat but rather stout and rubbery-solid, strong, resistant and even defiant; of an indeterminate age beyond forty with a girl’s plaintive face inside the puffy face of the aggrieved middle-aged woman.

Please—you sayin you seen her? Ohhh but—when? Since Thu’sday? That’s two days ago and two nights she been missin …

Along wide windy Trenton Avenue there came Ednetta Frye lurching into the Diamond Café, and into the Wig-a-Do Shop, and into AMC Loans & Bail-Bond, and into storefront Goodwill where the manager offered to call 911 for her to report her daughter missing and Ednetta said with a little scream drawing back with a look of anguish No! No po-lice! How’d I know the Pascayne police ain’t the ones taken my girl!

Exiting Goodwill stumbling in the doorway murmuring to herself O God O God don’t let my baby be hurt O God have mercy.

Sighted then making her way past shuttered storefront businesses on Trenton Avenue and then to Penescott to Freund which were blocks of brownstone row houses converted into apartments and so to Port and Sansom which were blocks of small single-story stucco and wood frame bungalows built close to cracked and weed-pierced sidewalks. An observer would think that the distraught woman’s route was haphazard and whimsical following an incalculable logic. Sometimes she crossed the street several times within a single block. There were far fewer people on these residential streets so Ednetta knocked on doors, called into dim-lighted interiors, several times boldly peered into windows and rapped on glass—’Scuse me? Hello? C’n I ask you one thing? This my daughter S’b’lla Frye she missin since Thu’sday—you seen anybody looks like her?

Crossing vacant lots heaped with debris and along muddy alleys whimpering to herself. She’d begun to walk with a limp. She was panting, distracted. She seemed to have taken a wrong turn, but did not want to retrace her steps. Somewhere close by, a dog was barking furiously. Overhead, a plane was descending to Newark International Airport with a deafening roar—Ednetta craned her neck to stare into the sky as at a sign of God, unfathomable and terrible. Here below were abandoned and derelict houses, a decaying sandstone tenement building on Sansom long known as a hangout for drug addicts, teenagers, homeless and the mentally ill which Ednetta Frye approached heedlessly. H’lo? Anybody in here? H’lo! H’lo!

And daring to step into the street to stop vehicles to announce to the startled occupants ’Scuse me! I am Ednetta Frye, this is my daughter S’b’lla Frye, she fourteen years old. Last I seen of S’b’lla she be leavin for school and now they sayin she never got there. This was Thu’sday.

She passed the pictures of Sybilla to these strangers who regarded them somberly, handed them back to Ednetta and assured her no, they hadn’t seen the girl but yes, they would be on the lookout for her.

At Sansom and Fifth there came sharp gusts of wind from the river, fresh-wet air and a sickly-sweet odor of leaves and strewn garbage in the alleys. And there stood Ednetta Frye on the curb pausing to rest like a laborer who is exhausted after an effort that has come to nothing. No one so alone as the bereft mother seeking her lost child in vain. The heel of her hand pressed against her chest as if she were stricken with heart-pain and she was staring into the distance, at the Pitcairn Bridge lifted and spread like a great prehistoric predator-bird and beyond at the slow bleed of the sky and on her face tears shone unabashed, so little awareness had Ednetta of these tears she hadn’t lifted a hand to wipe them away.

THAT POOR WOMAN SHE SCARED OUT OF HER WITS LIKE SHE AIN’T EVEN aware who she talkin to!

Primarily it was women. During Ednetta Frye’s several hours of search and inquiry in the Camden Avenue–Twelfth Street neighborhood of inner-city Pascayne on the morning of October 6, 1987.

Some sixty individuals would recall Ednetta, afterward.

Of these a number were women who knew Ednetta Frye from the neighborhood and who’d seen her frequently with children presumed to be hers including the daughter Sybilla—but they hadn’t seen Sybilla within the past forty-eight hours, they were sure.

Of these were women who’d known Ednetta Frye for years—as long as thirty, thirty-five years—when they’d been girls together in the old Roosevelt projects, long since condemned and razed and replaced by a never-completed riverfront “esplanade” that was a quarter-mile sprawl of concrete and mud, rusted chain-link fences, frayed flapping plastic signs danger do not enter construction. They’d gone to East Edson Elementary in the 1950s and on to East Edson Middle School and to Pascayne South High. Some of them had known Ednetta when she’d been a young mother—(she’d had her first baby at sixteen, forced to quit school and never returned)—and during those years when she’d worked part-time as a nurse’s aide at the Polk clinic taking the Clinton Street bus along Camden Avenue, a husky straight-backed good-looking woman with a gat-toothed smile, warm-rippling laughter that made you want to laugh with her.

And there were those who’d known Ednetta in the past decade or so since she’d been living with Anis Schutt in one of the row house brownstones on Third Street. Some of these women who’d known Anis Schutt when he’d been incarcerated at Rahway maximum-security and before that at the time of Anis’s first wife’s death—“manslaughter” was the charge Anis had pleaded to—had (maybe) wondered at Ednetta who was younger than Anis by at least ten years falling in love with such a man, taking such a risk, and her with three young children.

Ednetta had always belonged to the AME Zion Church on First Street.

She’d sung in the choir there. Rich deep contralto voice like Marian Anderson, she’d been told.

Good-looking as Kathleen Battle, she’d been told.

Never missed church. Sunday mornings with her mother and her grandmother (her old ailing grandmother she’d helped nurse) and her aunts and her girls Sybilla and Evanda, Ednetta’s happiest times you could see in her face.

Anis Schutt never came to the AME Zion Church. No man leastway resembling Anis Schutt was likely to come to the AME Zion Church where the shock-white-haired minister Reverend Clarence Denis frequently preached himself into a frenzy of passion and indignation on the subject of “taking back” Red Rock from the “thugs and gangsters” who’d stolen it from the good black Christian people.

A few years ago there’d been a rumor of Ednetta Frye fired from the Polk clinic for (maybe) stealing drugs. Ednetta Frye charged with “bad checks” when it was claimed by her that she’d been the victim. Ednetta working at Walmart—or Home Depot—one of those big-box stores at the Pascayne East Mall where you were lucky to get minimum wage and next-to-no health benefits but you could buy damaged and outdated merchandise cheap which all the employees did especially at back-to-school and Christmas time.

Over the years there’d been rumors of ill health: diabetes? arthritis? (Seeing how Ednetta had put on weight, fifty pounds at least.) Taking the children to relatives’ homes to hide from Anis Schutt in one of his bad drunk moods but Ednetta had not ever called 911 and had not ever fled to St. Theresa’s Women’s Shelter on Twelfth Street as other women (including her younger sister Cheryl) had done at one time or another nor had she gone to Passaic County Family Court to ask for an injunction to keep Anis Schutt at a distance from her and the children.

Ednetta Frye, who loved her children. Who did most of the work raising Anis Schutt’s several children (from his only marriage, with the wife Tana who’d died) along with her own—five or six of them in the cramped household though Anis’s boys being older hadn’t remained long.

One of the sons at age nineteen shot dead on a Newark street in a drive-by fusillade of bullets.

Another son at age twenty-three incarcerated at Rahway on charges of drug-dealing and aggravated assault, twelve to twenty years.

They were an endangered species—black boys. Ages twelve to twenty-five, you had to fear for their lives in inner-city Pascayne, New Jersey.

Ednetta had a son, too—ten years old. And another, younger daughter, Sybilla’s half-sister.

Of the women to whom Ednetta Frye showed Sybilla’s picture this morning several knew Anis Schutt “well” and at least two of them—(Lucille Hersh, Marlena Swann)—had had what you’d call “relations” with the man, years before.

Lucille’s twenty-year-old son Rodrick was Anis’s son, no doubt about that. Marlena’s eight-year-old daughter Angelina was Anis’s daughter, he’d never contested it. Exactly how many other children Anis had fathered wasn’t clear. He’d started young, as Anis said, laughing—hadn’t had time for counting.

It was painful to Ednetta of course—running into these women. Seeing these women cut their eyes at her.

Worse, seeing these women with children the rumor was, Anis was the father. That was nasty.

You could see that poor woman scared out of her wits like she ain’t even aware who she talking to. I saw it myself, Ednetta come up to me an my friend Jewel in the grocery like she never knew who we were—Ednetta Frye be Jewel’s enemy on account of Anis who ain’t done shit to help Jewel out, all the time he promise he would. And Ednetta looks at us with like these blind eyes sayin ’Scuse me! Hopin you can help me! My daughter S’b’lla—you seen her?

That big girl gone only a day or two and Ednetta was actin like the girl be dead, we thought it was kind of exaggerated but when you’re a mother, you do worry. And when a girl is that age like S’b’lla, you can’t trust her.

You wouldn’t ask Ednetta if she’d called the police, knowin how Anis feel about police and how police feel about Anis.

So we said to her, we will look for S’b’lla for sure! We will ask about her, everyone we know, and if we see her, or learn of her, we will inform Ednetta right away.

And she was cryin then, she like to hugged us hard and she say, Thank you! And God bless you, I am praying He will bless me and my baby and spare her from harm.

And we stand there watchin that poor woman walk away like she be drunk or somethin, like she be walkin in her sleep, and we’re sayin to each other what you say at such a time when nobody else can hear—Poor Ednetta Frye, sure am happy I ain’t her!

The Discovery

OCTOBER 7, 1987

EAST VENTOR AT DEPP

PASCAYNE, NEW JERSEY

You hear that? That like cryin sound?”

In the night she’d heard it, whatever it was—had to hope it wasn’t what it might be.

Might be a trapped bird, or animal—not a baby … She didn’t want to think it might be a baby.

A soft-wailing whimpering sound. It rose, and it fell—confused with her sleep which was a thin jittery sleep to be pierced by a sliver of light, or a sliver of sound. Those swift dreams that pass before your eyes like colored shadows on a wall. And mixed with night-noises—sirens, car motors, barking dogs, shouts. The worst was hearing gunshots, and screams. And waiting to hear what came next.

She’d lived in this neighborhood of Red Rock all of her life which was thirty-one years. Bounded by the elevated roadway of the New Jersey Turnpike some twelve blocks from the river, and four blocks wide: Camden Avenue, Crater, East Ventor, Barnegat. Following the “riot” of August 1967—(riot was a white word, a police word, a word of reproach and judgment you saw in headlines)—Red Rock had become a kind of inner-city island, long stretches of burnt-out houses, boarded-up and abandoned buildings, potholed streets and decaying sidewalks and virtually every face you saw was dark-skinned where you might recall—(Ada recalled, as a child)—you’d once seen a mix of skin tones as you’d once seen stores and businesses on Camden Avenue.

She’d gone to Edson Elementary just up the block. She’d taken a bus to the high school at Packett and Twelfth where she’d graduated with a business degree and where for a while she’d had a job in the school office—typist, file clerk. There were (white) teachers who’d encouraged her to get another degree and so she’d gone to Passaic County Community College to get a degree in English education which qualified her for teaching in New Jersey public schools where sometimes she did teach, though only as a sub. There was prejudice against community-college teacher-degrees, she’d learned. A prejudice in favor of hiring teachers with degrees from the superior Rutgers education school which meant, much of the time, though not all of the time, white or distinctly light-skinned teachers. Ada didn’t want to think it was a particular prejudice against her.

She’d lain awake in the night hearing the faint cries thinking it was probably just a bird trapped in an air shaft. This old tenement building, five floors, no telling what was contained within the red-brick walls or in the cellar that flooded in heavy rainfall when the Passaic overflowed its banks and sewage rushed through the gutters. A pigeon with a broken wing, that had flung itself against a windowpane. A stray dog that had wandered into the building smelling food or the possibility of food and had gotten trapped somewhere when a door blew shut.

“Nah I don’t hear nothin’. Aint hearin anything.”

“Right now. Hear? It’s somebody hurt, maybe …”

“Some junkie or junkie-ho’. No fuckin way we gonna get involved, Ada. You get back here.”

Ada laughed sharply. Ada detached her mother’s fingers from her wrist. She was a take-charge kind of person. Her teachers had always praised her and now she was a teacher herself, she would take charge. She wasn’t the kind of person to ignore somebody crying for help practically beneath her window.

Down the steep creaking steps with the swaying banister she was having second thoughts. In this neighborhood even on Sunday morning you could poke your nose into something you’d regret. Ma was probably right: drug dealers, drug users, kids high on crack, hookers and homeless people, somebody with a mental illness …

She couldn’t hear the cries now. Only in her bedroom had she really heard, distinctly.

Years ago the factory next-door had been a canning factory—Jersey Foods. Truckloads of fish gutted and cooked and processed into a kind of mash, heavily salted, packed into cans. And the cans swept along the assembly line, and loaded into the backs of trucks. Tons of fish, a pervading stink of fish, almost unbearable in the heat of New Jersey summers.

Jersey Foods had been shut down in 1979 by the State Board of Health. The derelict old building was partially collapsed, following a fire of “suspicious origin”; its several acres of property, including an asphalt parking lot with cracks wide as crevices, as well as the rust-colored building, lay behind a six-foot chain-link fence that was itself badly rusted and partially collapsed. Signs warning no TRESPASSING had not deterred neighborhood children from crawling through the fence and playing in the factory despite adults’ warnings of danger.

In the other direction, on the far side of the dead end of Depp Street, was another shuttered factory. Even more than Jersey Foods, United Plastics was off-limits to trespassers for the poisons steeped in its soil.

You’d think no one would be living in this dead-end part of Pascayne—but rents were cheap here. And no part of inner-city Pascayne was what you’d call safe.

It was Ada’s hope to be offered a full-time teacher’s job in an outlying school district in the city, or in one of the suburbs. (All of the suburbs were predominantly white but “integrated” for those who could afford to live there.) Then, she’d move her family out of squalid East Ventor.

Six years she’d been hoping and she hadn’t given up yet.

“God! Don’t let it be no baby.”

(Well—it wouldn’t be the first time a baby had been abandoned in this run-down neighborhood by the river. Dead-end streets, shut-up warehouses and factories, trash spilling out of Dumpsters. Some weeks there wasn’t any garbage pickup. A heavy rain, there came flooding from the river, filthy smelly water in cellars, rushing along the gutters and in the streets. Walking to the Camden Street bus Ada would see rats boldly rooting in trash just a few feet away from her ankles. [She had a particular fear of rats biting her ankles and she’d get rabies.] Nasty things fearless of Ada as they were indifferent to human beings generally except for boys who pelted them with rocks, chased and killed them if they could. And what the rats might be dragging around, squeaking and eating and their hairless prehensile tails uplifted in some perky way like a dog, you didn’t want to know. For sure, Ada didn’t want to know. Terrible story she’d heard as a girl, rats devouring some poor little baby left in some alley to die. And nobody would reveal whose baby it was though some folks must’ve known. Or who left the baby in such a place. And the white cops for sure didn’t give a damn or even Family Services and for years Ada had liked to make herself sick and scared in weak moods thinking of rats devouring a baby and so, whenever she saw rats quickly she turned her eyes away.)

Ada was uneasy remembering Ednetta Frye from the previous morning. She’d seen the distraught woman first crossing Camden Avenue scarcely aware of traffic, then in the Korean grocery, then approaching people in Hicks Square who stared at her as you’d stare at a crazy person. Ednetta had seemed so distracted and disoriented and frightened, nothing like her usual self you could talk and laugh with—it was Ednetta who did most of the talking and the laughing at such times. There’d been occasions when Ednetta had a bruised face and a swollen lip but she’d laugh saying she’d walked into some damn door. You guessed it had to be Anis Schutt shoving the woman around but it wasn’t anything extreme, the way Ednetta laughed about it.

Ada was at least ten years younger than Ednetta Frye. She’d substitute-taught at the middle school when Ednetta’s daughter Sybilla had been a student there, a year or two ago; she knew the Fryes from the neighborhood, though not well.

They were neighbors, you could say. East Ventor crossed Crater and if you took the alley back of Crater to Third Street, somewhere right around there Ednetta was living in one of the row houses with that man and her children—how many children, Ada had no idea.

With her education degree and New Jersey teacher’s certificate Ada Furst liked to think that there was something like a pane of glass between herself and people like the Fryes—it might be transparent, but it was substantial.

But the day before, Ednetta hadn’t been in a laughing or careless mood. She’d been anxious and frightened. She’d showed Ada photos of Sybilla as if Ada didn’t know what Sybilla looked like—Ada had had to protest, “Ednetta, I know what Sybilla looks like! Why’re you showing me these?”

Ednetta hadn’t known how to answer this. Stared at Ada with blank slow-blinking eyes as if she hadn’t recognized Ada Furst the schoolteacher.

“She’s probably with some friends, Ednetta. You know how girls are at that age, they just don’t think.”

Ednetta said, “S’b’lla know better. She been brought up better. If Anis get disgusted with her, he goin to discipline her—serious. S’b’lla know that.”

Ada said another time that Sybilla was probably with some friends. Ednetta shouldn’t be worried, just yet.

“I don’t know how long you’d be wantin me to wait, to be ‘worried,’” Ednetta said sharply. “I told you, Anis don’t allow disrespectful behavior in our house. S’b’lla got to know that.”

Clutching her photographs Ednetta moved on. Ada watched the woman pityingly as she approached people on the street, imploring them, practically begging them, showing the pictures of Sybilla. Most people acted polite, and some were genuinely sympathetic. There was something not right about what Ednetta was doing, Ada thought. But she had no idea what it was.

Ada was ashamed now, she’d spoken so inanely to Ednetta Frye. But what did you say? Girls like Sybilla were always “running away”—Ada knew from being a schoolteacher—meaning they were staying with some man likely to be a dozen years older than they were, and giving them drugs. What she could remember of Sybilla Frye from the middle school, the girl was sassy and impudent, restless, couldn’t sit still to concentrate, had a dirty mouth to her, and hung out with the wrong kind of girls. Her grades were poor, she’d be caught with her friends smoking out the back door of the school—in seventh grade. None of that could Ada tell poor Ednetta!

Ada knocked at the second-floor door of a woman named Klariss—just a thought, she’d ask Klariss to come with her. But Klariss was as vehement as Ada’s mother. “You keep outa that, Ada. You know it’s some drug dealer somebody put a bullet in, or some druggie OD’ing. You get mixed up in it, the cops is gonna mix you up with them and take you all in.”

Weakly Ada tried to cajole Klariss into at least coming outside with her, in back of the building—“You don’t have to come any farther, K’riss. Just, like—see if anything happens …”

But Klariss was shutting her door.

In the front vestibule were several tall teenaged boys on their way outside—ebony-black skin, mirthful glances exchanged that signaled their awareness of / disdain for stiff-backed Ada Furst they knew to be some kind of schoolteacher—(these were boys born in Red Rock of parents from the Dominican Republic who lived upstairs from Ada)—and for a weak moment Ada considered asking them to accompany her … But no, these rude boys would only laugh at her. Or something worse.

Outside, Ada walked to the rear of the building. No one ever went here, or rarely: behind the tenement was a no-man’s-land of rubble-littered weeds and stunted trees, sloping to a ten-foot wire fence at the riverbank, against which years of litter had been blown and flattened so that it resembled now some sort of plaster art installation. In this lot tenants had dumped trash that included refrigerators, mattresses, chairs and sofas and even badly broken and discolored toilets. (Ada recognized a broken lamp that had once belonged to Kahola, her sister must’ve tossed out here. For shame!)

Ma and Karliss were right: Ada shouldn’t be here. Hadn’t there been a murder in this block, only a week ago, one in a series of young black boys shot multiple times in the back of the head, dragged into an abandoned house to bleed out and die …

But this person, if it was a person, was alive. Needing help.

Noise from jetliners in their maddening ascent from Newark Airport a few miles away, that began in the early morning and continued for hours even on weekends. Ada couldn’t hear the crying sound, with those damn jets!

Ada checked to see: was anyone following her? (The tall black-skinned Dominican boys, who hadn’t said a word to her though she’d smiled at them?) She made her way through the debris-strewn lot to the fence, that overlooked the river. Here she felt overwhelmed by the white, vertically falling autumn sunshine, that blinded her eyes. And the wide Passaic River with its lead-colored swift-running current that looked to her like strange sinewy transparent flesh, a living creature with a hide that rippled and shivered in the sunshine. Oil slicks, shimmering rainbows. The Passaic had once been a beautiful river—Ada knew, from schoolbooks—but since the mid-1800s it had been defiled by factories and mills dumping waste, all sorts of debris, tannery by-products, oil, dioxin, PCBs, mercury, DDT, pesticides, heavy metals. Upriver at Passaic was Occidental Chemical, manufacturers of the most virulent man-made poison with the quaint name—Agent Orange. Supposedly now in the late 1980s in these more enlightened times manufacturers had been made to comply with federal and state environmental laws; cleanups of the river had begun but slowly, at massive cost.