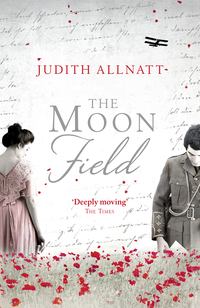

Loe raamatut: «The Moon Field»

THE

MOON FIELD

JUDITH ALLNATT

In memory of my mother,

Isabel Gillard,

with love and admiration.

No man’s land is a place in the heart: pitted, cratered and empty as the moon.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Maps

Prologue

Part One: First Post

1. Watercolour

2. At the Twa Dogs

3. Dance Card

4. Measuring Up

5. Friar’s Crag

6. Feathers on the Stream

7. Blue Envelope

Part Two: Flanders, Autumn 1914

8. Polders

9. Studio Portrait

10. Home Comforts

11. Playing Cards

12. Earth

13. The Ruined House

Part Three: Blighty

14. Christmas Post

15. Tin

16. 26 Leonard Street

17. Breaking

18. The Alhambra

19. Cat Bells

20. Paste Brooch

21. The Walled Garden

22. Castlerigg

23. Stones

24. No Man’s Land

25. Walking Out

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

A Q&A with Judith Allnatt

About the Author

Also by Judith Allnatt

Copyright

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

The lid of the tin box is tight; you have to move from one corner to another, prising and pushing with your thumbs. Green paint peels from its edges as though time has been gnawing at it. Brown patches of rust have pockmarked its surface, but you can still make out the picture: a man and a woman in a rowing boat, oars shipped, he with a fishing rod, she with a red parasol, the gentle slopes of tree-lined banks, the river calm, sun-dappled. ‘Jacob and Co’s “Water” Biscuits’ reads the legend, as if the biscuits were meant only to be enjoyed when boating, conjuring lazy, sun-filled days suspended in the lap of the water, with time to drift, to float …

The lid comes loose with a faint gasp of released air. Inside are papers and objects, loosely packed. There is a bundle of letters, the expensive blue writing paper tied, oddly, with a bootlace. A pack of Lloyd’s cigarettes has a faint smell of tobacco and an even fainter trace of roses. There are photographs: stiffly posed family portraits of men and women in high collars; a girl playing tennis, one hand bundling the encumbrance of her long skirts aside as she reaches for her shot; hand-tinted postcards of lakeside views.

The heavier objects have found their way to the bottom: an amber heart, a pocket watch, a set of keys, and an ivory dance-card holder with a tiny ebony pencil. Lifted, each one fits your hand, makes a hieroglyph: the shape of the past against your palm. This was real; I was there, they say as you feel their weight and smoothness.

Beneath them, lining the tin, is the stiff paper of a watercolour painting, slightly foxed and with its edges curling a little but still with its landscape greens and blues, the texture of the paper showing through the brushstrokes of some unknown hand.

PART ONE

1

WATERCOLOUR

Today would be the day. George touched the bulky package in the breast pocket of his postman’s uniform as if to check, one more time, that it was there. His best watercolour was pressed between the pages of his sketchbook to keep it flat and pristine, as a gift should be. He felt his heart beating against the board back of the book. All morning it had been beating out the seconds, the minutes and the hours between his decision and the act. Today, when he went on the last leg of his rounds, he would present Violet with the painting over which he had laboured. ‘As a token of my esteem,’ he would say, for, even to himself, he dared not use the word love.

In the sorting room at the back of the post office, he greeted the others, hung his empty bag on its hooks at the sorting table so that it sagged open, ready to be filled, and leant against the wall to take a few moments’ rest. The late-morning sun slanted down through the high windows, alive with paper dust that rose from the table: a vast horse-trough affair with shuttered sides. Kitty and her mother, Mrs Ashwell, their sleeves rolled up, picked at the choppy waves of letters, their pale arms and poised fingers moving as precisely as swans dipping to feed. Every handful of mail, white, cream and bill-brown, was shuffled quickly into the pigeonholes that covered the rear wall, each neatly labelled street by street.

‘I see Mrs Verney’s Christopher has a birthday,’ Kitty said as she pressed a handful of envelopes into ‘20–50 Helvellyn Street’.

‘He’s reached his majority,’ Mrs Ashwell said. ‘Let’s hope he’s soon home to enjoy it.’

Mr Ashwell, the postmaster, came in carrying a sack of mail over his shoulder. He nudged George and thrust the sack into his arms. ‘Dreaming again, George?’ he said. ‘You left this one by the counter right where I could trip over it.’

‘Sorry, sir,’ George said quickly.

Mr Ashwell made some show of dusting off his front and pulling his waistcoat down straight. ‘Concentration, young man,’ he said, giving George one of his straight looks. ‘Concentration is needed to make sure that work proceeds in an orderly manner.’ He stroked his moustache with his finger and thumb while continuing to fix George with his gaze. George felt his cheeks begin to burn.

Mr Ashwell said, without looking at his wife, ‘Very busy on the counter today, Mabel. Tea would be most acceptable. Arthur’s assistance sorely missed.’

Mrs Ashwell’s hands stilled amongst the letters and her back stiffened as if to brace herself against the thought of her son, so far from home. Through the doorway between the sorting room and the shop, she could see Arthur’s old position at the counter. The absence of his broad back and shoulders, of the familiar fold of skin over his tight collar and the neatly cut rectangle of brown hair at his neck struck her anew each time she let her glance stray that way. It was as though someone had punched out an Arthur-shaped piece of her existence and pasted in its place a set of scales and a view of the open post office door and the cobbled street beyond.

Sometimes, when the post office was closed and Mr Ashwell busy elsewhere, she would stand in Arthur’s old place and rest her elbows where his had rested. She would bow her head and finger through the set of rubber stamps as if they were rosary beads. At these moments, she tried not to look at the noticeboard on the side wall. Amongst the public notices of opening hours and postal rates was the sign that her husband had insisted be displayed, just as all official documents that were sent from head office must be. An innocuous buff-coloured sheet of paper that one might easily overlook, thinking it yet another piece of dull information, it read:

POST OFFICE RIFLES –

The postmaster’s permission to join must be sought.

Pay is equal to civil pay for all Established Officers plus Free Kit, Rations and Quarters.

GOD SAVE THE KING.

The detailed terms and conditions followed in smaller print below.

Mrs Ashwell thought about the boredom of the counter job on a quiet afternoon, of how Arthur’s eyes must have run over and over all the notices: ‘Foreign packages must be passed to the counter clerk.’ ‘Release is for one year’s service.’ ‘This office is closed on Sundays and official holidays.’ ‘Remuneration will be at an enhanced rate.’ She imagined the phrases repeating in his mind as he tinkered with the scales, idly building pyramids of brass weights on the pan.

‘Tea,’ she said, under her breath. Then more determinedly: ‘Tea,’ and went upstairs to their living quarters to make it.

George hefted the sack up on to the table and upended it, spilling a new landslide of mail that re-covered the chinks of oak board that had begun to show through.

‘Is that the last bag?’ Kitty asked of her father’s retreating back.

‘Better ask George if he’s left any more lying about,’ he said and closed the door behind him.

Kitty rolled her eyes at George. ‘He’s been like a bear with a sore head ever since breakfast. We got Arthur’s first letter,’ she added.

George came round to her side of the table and they sorted side by side, their heads bent companionably together, George’s fair hair ruffled where he had run his hands through it in the heat, Kitty’s springy, pale brown hair tied back neatly out of the way. George waited for her to elaborate about Arthur but Kitty bent her head to her work and pressed her lips together. After a while, when the job was almost done, George said in his slow, gentle way, ‘It must be a terrible worry for your father.’

Kitty snorted. ‘Quite to the contrary; Arthur is travelling further afield than Penrith and preparing to tackle the enemy, whereas Father is still chained to the counter like a piece of pencil on a string.’

‘Aah,’ said George, pausing to look at her more closely. ‘And how about you, Kitty? How are you bearing up?’

‘I miss him, but it makes me sad to see Mother miss him even more and it makes me cross that Father won’t let the subject rest.’ She tapped the letters in her hand smartly on their side to line them up, shoved them roughly into a pigeonhole and then, seeing her mistake, pulled them back out again.

George laid his hand on her shoulder. ‘Oh, Kit,’ he said. ‘I’m so sorry.’

She gave him a half-hearted smile. ‘Never mind. What was it we used to say at school on bad days?’

‘All manner of things shall be well,’ George said slowly.

‘Exactly.’ She looked again at the address on top of her pile of mail and placed it carefully into the correct wooden cubby-hole. ‘Here, give us your bag,’ she said. ‘I’ll fill it up.’

He held the bag open while she put in the packages of post to be delivered to the villages; then she parcelled up each street with string and dropped them in on top. She helped him on with the bag, reaching up to lift the strap over his shoulder and then settling the weight at his back.

‘Sorry it’s a heavy one,’ she said.

‘It’s cutting down the number of deliveries that’s done it. Bound to be heavy.’

She buckled the bag and gave it a pat. ‘See you later,’ she said. ‘We’ve got plum bread for tea. I’ll save you some.’

George nodded and went out through the post office, past the dour looks of Mr Ashwell and a queue of chattering customers and into the brightness of the day. The market place seemed just as busy as usual; almost impossible to believe that the country was at war: shoppers were choosing vegetables, lengths of cloth and ironmongery from the carts lined up in rows in the centre of the square, each cart tipped forward to rest on its shafts, the better to show the goods. The calls of the vendors mixed with the barking of dogs and the rumble of a motor charabanc passing along St John’s Street. The sky was a hazy white and the green flanks of the hills rose in the distance behind the tower of the Moot Hall, their lines as familiar to him as the lineaments of his own face. Taking a deep breath to clear his lungs of the indoor smell of the post office, he caught the musky odour of horse dung and the sharper tang of motor oil. He paused to adjust the strap of the postbag and loosen his tie a little; then he turned down the alley at the side of the post office to collect his bike. He wheeled it out, leaning its saddle against his thigh, and went on in this fashion, bumping over the cobbles, past the Moot Hall and into the narrow streets beyond.

The bike was a heavy, black, iron thing with a basket the size of a lobster pot and when George first got it, he’d not been able to manage it on the steep inclines. He’d needed to get off halfway up a hill and walk it up the rest, sweat darkening his fair hair and sticking it to his forehead. He had persevered though, pedalling a little further each time, thinking of his body as an engine that would benefit from work, and taking pleasure in the healthy ache of his muscles at the end of a day. His uniform jacket had needed to be let out along the back seam to allow for the growing breadth of his shoulders, and his mother, fitting the jacket on him, had called him an ‘ox of a man’ and made him smile. Now, by standing up on the pedals he could force the bike uphill, clanking and complaining, his solid frame bent over the handlebars, shoulders hunched and front wheel wobbling as he slowed for the steepest slopes. Having the bike meant that he could deliver to the farms and hamlets. His spirits lifted as soon as he got out among the fells and he happily left the younger boys to divide the rest of the town between them and deliver on foot carrying lightly loaded bags and returning more frequently to the office to refill them.

George forced himself to walk at his usual pace along the street and up and down the steps of the guesthouses. There was no point hurrying, he told himself sternly, because if he arrived at the Manor House early she would still be lunching and he would have to deliver the family’s letters to the gatehouse, and would miss his chance again. No, he had to do everything as usual and must not leave the town until the Moot Hall clock struck one. That would bring him to the grounds around two o’clock, just as she set out down the lane from the house to take her walk but before she turned off right for the fell or left for the fields and the river.

It had been at the bridge that he had first seen her. He had almost not noticed her in the dappled shadows of the alders that grew beside the river, right close against the stonework of the bridge; only the brightness of her white blouse had given her away, she was so still. She was holding a brown box in both hands and leaning against the parapet. George was struck by the way her straight brown hair was caught in a twist that sat neatly at the nape of her neck and how her posture, leaning forward to focus intently on something below, accentuated the slenderness of her waist. He slowed the bike, thinking to pass on the far side of the narrow bridge without disturbing her but the crackle of the wheels over the grit caught her ear and she turned, her hands still holding the object in front of her and looked at him as if puzzled for a moment. Her face … pale, with dark eyes, forehead slightly drawn, as if coming round from sleep, high cheekbones and full lips, which ran into upward indentations at the corners suggesting the tantalising possibility of a smile that was at odds with the serious expression of her eyes. Without even thinking, he put one foot down on the ground and stopped dead.

‘What are you doing?’ he said, blurting it out into the moment before she could turn away.

‘Preparing to take a photograph,’ she said.

He got off the bike and wheeled it over to her. His family had only one photograph, a studio portrait of his parents: his mother seated, wearing her bridal gown, veil and circlet of flowers; his father standing stiffly behind her, one hand resting on her shoulder.

She said, ‘I want to catch the way the light is reflecting off the water on to the rock,’ and pointed at the boulders that were tumbled midstream, the current divided by them into shining cords that glittered and threw up shifting patterns on their undersides.

He nodded and they stood together watching the movement and listening to the rush and trickle of the water over the bed of smaller stones.

‘Can you see a pattern in it?’ she asked.

‘Nearly …’ he said, for it seemed that there was a pattern though it was complex and hidden just beyond his ability to grasp it.

She turned to him. ‘You’re right,’ she said. ‘A nearly pattern. It’s just a little too quick for us to follow.’

She held the camera up again and looked down through the viewfinder. She sighed and passed it to him, saying, ‘What do you think? It’ll be impossible to catch the sense of motion, of course.’

The viewfinder had a greyish tint and George looked through it at a scene transformed in an instant to cooler tones. Gnats showed like grey dots above the surface of the water, their dancing as complex as the lights on the rocks beside them. Without the glare, the shifting lights were softer. He could see, on the shady side of the stones, dark bars beneath the water.

‘There are trout,’ he said, ‘lying up out of the heat.’

‘Are there? Where?’ She peered over the parapet at where he pointed. ‘Are you an angler?’ she asked.

George shrugged. ‘I fish a bit. Mostly I just look a lot and so I see things.’

She gave a little smile and he blushed as if he had said something stupid. He gave the camera back to her. ‘Will it be in colour? The picture?’ he asked, making an effort to conquer his shyness.

She nodded. ‘The new film still isn’t as close to a natural palette as one would like; it’s better than monochrome though.’

‘Except for in the snow,’ George said.

That smile again. George’s heart turned over. ‘I prefer painting,’ he blurted out; then, fearing he’d been rude: ‘I mean you can get the real colours then, all of them. I like going up on the fells in the evenings when there are greys and purples and the rust of the bracken, not just green, the slopes aren’t ever just green …’

She looked at him then. Not as if he was being dull, as his little brother, Ted did, or as if he was unhinged as Arthur had once when he spoke to him about painting, but as if she was really, truly listening. She said, ‘… and clouds aren’t ever only white any more than the water’s ever only blue. Do you go down to Derwentwater to paint?’

‘Sometimes,’ George said, ‘and out on the tops: Cat Bells, Helvellyn. But I haven’t always got paints; sometimes I sketch. It’s expensive, you know.’

‘I don’t always take the camera,’ she said, ‘sometimes I just sketch too.’ She held out her hand. ‘Violet Walter. I live back there.’ She pointed towards the trees, beyond which, George knew, lay only one house, the Manor House with its grey roofs and many chimneys, impressive even against the rising ranks of evergreens that finished like a tideline halfway up the huge bulk of Ullock Pike, which over-towered all.

‘George Farrell,’ he said, taking her pale, perfectly smooth hand in his, then letting it go quickly in fear that she would think him too familiar. ‘P-P …’ he stuttered over the word ‘postman’.

‘Painter,’ she said and smiled.

That had been in May. The first month he had looked for her often but his searching had been in vain because he had later learnt that she had been away. She told him that she had been staying with Elizabeth Lyne, an old school friend in Carlisle: describing another world of tea taken on the lawn, with white cloths under spreading elms, and dancing after twilight, music spilling like magic from the open throat of the gramophone.

He had kept looking and had eventually been rewarded. Sometimes he just glimpsed a distant figure on the hillside as he passed with his bike and bag along the road below; then she would raise her hand to him and he to her, in salutation. Sometimes she would be coming towards him from home with her camera in its leather box slung across her shoulder and he would give her the letters for the house. Almost every day, in among a sheaf of bills in brown envelopes, there would be one creamy envelope for her with a Carlisle postmark. She would shuffle through the letters until she saw it and then stow it in one pocket and put the rest in the other. He imagined that she must miss her friend badly and feel the isolation of the spot after her companionable stay in the town.

When he had passed over the letters, he would turn around so that he could walk with her a while. He would wheel the bike alongside; her camera stowed with the post in the basket so that she might have a hand free to hold her long skirt clear of the dusty road. If she had letters of her own to send, in the pale blue envelopes she favoured, they would walk first to the postbox before strolling on, out into the countryside. Sometimes, the best times, when he climbed a track to one of the lonely hill farms, he would come across her leaning on a gate looking out over the valley and he would join her to share the view. They talked of the way the clouds chased the light over the hills, and of the hawks nesting in the copse near the house, which hovered, dark specks in the heavens, giving perspective and making the piled clouds mountainous.

George learnt that she was older than he was by three years. ‘An old lady of twenty-one,’ she said. An only child, she had been educated at a boarding school in Carlisle, then a finishing school in France. She spoke of its beauty: the French countryside softer than Cumberland with hedges rather than walls, low slopes and wide plains of rich pasture and standing crops. She described the rocky coast of Brittany, its crashing waves and spume-filled air, and a Normandy beach with a wide arc of sand, which she had walked from end to end, slipping away from her school party to watch the gannets dive like black arrows into the sea. Her eyes lit up as she told him of such things and she motioned with her hands to trace the sweep of the bay or the birds’ headlong plunge. Once he told her that looking out over the lake from the top of the fells was what made him certain that he had a soul, and she had touched his arm and said, ‘Yes, yes.’

He had told her how it had been at his school. How he was different, always in trouble when the master asked him a question and he was unable to answer because he had been staring out of the window at the clouds, making dragons and faces and genies from their ever-changing shapes. He had said less and less the more he grew afraid that he would get it wrong, until the other children called him ‘moony’ and ‘idiot’ and ‘simple’.

‘You’re far from simple, George,’ she said. ‘They mistook the distraction that comes from hard thought for no thought at all, and that’s their error.’ She touched his sleeve again and he thought his heart would burst with pride because although Kitty and his mother had always said such things this was different.

When she spoke of her parents, she always had a note of worry in her voice. Her father was often abroad attending to his business interests, leaving the land and Home Farm to the estate manager, and her mother to her own resources. Mrs Walter, too much alone, suffered ‘sick-headaches’ and fatigue and often withdrew to her room. Violet once let slip that her father, even when back in London, frequently stayed at his club and George wondered what had caused the breach between her parents, but asked no further, guessing at the hurt that a daughter would feel to know that she was not enough to tempt a father home.

From her room, Mrs Walter instructed the housekeeper, Mrs Burbidge, and took her lunch on a tray. Afterwards she wrote letters, but later in the afternoon, she required Violet’s company, wanting her to sit with her and talk or read aloud. As the sun grew hotter in the afternoon, George would notice Violet glancing back at the copse within which the house was hidden or at her silver wristwatch. He would rack his brain for a question. ‘What was the town like, where your school was? What did you sketch on your picnics?’ Anything to stop her saying the words he dreaded: ‘I must go.’

George rattled the latch of a garden gate and then stood stock-still to listen, in case he had missed the Moot Hall bell. He heard nothing but nonetheless quickened his pace, the bike wheels juddering as he turned into Leonard Street where he lived. As he bumped the bike to a stop outside the house, his mother came to the door to meet him carrying a package wrapped in paper and with Lillie hanging on to her apron and sucking her thumb.

‘I thought I heard you; you made such a clatter,’ his mother said. ‘Have you got a bit behind?’ She passed him the package of sandwiches and a billycan of cold tea.

‘Carry!’ Lillie said and let go of the apron to lift her arms up to him.

‘You mustn’t get behind, George. Mr Ashwell’s a tartar for punctuality.’

‘Carry!’ Lillie said again, imperiously, and George put the food down on the step and lifted her under the armpits: a bundle of warm body and petticoats. He put her on his shoulders where she grabbed on to handfuls of his hair.

‘Ow! Lillie!’ he said and loosened her fingers, laying them flat against his head.

‘Horsy! Horsy!’ Lillie said and George held on tight to her skinny knees and jogged obligingly up and down the street.

The sound of the Moot Hall bell reached him, a single sonorous note, and he lifted Lillie down, detaching her fingers from his ear as he did so, and handed her into his mother’s arms.

‘You’d better cut along,’ she said. ‘You’d think it was a holy calling the way Mr A. goes on about duty and professionalism and “the mail must get through in all weathers …”.’ But George was already on his way, billycan rattling from the handlebars and the corner of the sandwich packet clamped between his teeth as he ran with the bike to the end of the road, threw his leg over the saddle and freewheeled down Wordsworth Street.

He pedalled along the road towards the park and left the buildings behind him, out into the elation of open space and over the bridge where the river flowed shallow and glittering and ducks and moorhens pecked at the trailing green weed. He passed the bowling greens where men in whites and straw hats were playing a tournament, while the ladies and elderly gentlemen watched from the benches, and then he took the back paths through the exotic trees, keeping out of sight of the park keeper, who would curse at him and make him get off his bike and walk. Then he was out on Brundholme Road with open fields either side, the sun hot on his back, soaking through his dark uniform jacket like warm water, the material prickling through his shirt.

By the time he had delivered the mail to the village post offices and to the scatter of farms beyond, he was starting to worry that he would arrive too late and took the last farm track down from the hill at a rate that rattled his teeth. A mile or so further on along the main road to Carlisle he reached the familiar gatehouse and turned in to the drive through the wood, his way lined by the dark glossy leaves of rhododendrons and the straight boles of Scots pines. Here and there, copper beeches made a splash of colour against the massive bulk of Dodd Fell that rose up behind, cluttered with rocks and strewn with sheep: small, pale dots on its upper slopes.

As he rounded the bend to face directly into the sun, he was dazzled momentarily; he put his hand up to his brow and squinted. A familiar figure, carrying a brown leather box, was making leisurely progress along the drive towards him. His pulse quickened. He felt a sensation run through him like a current through a wire making his grip on the handlebars tighten and his sense of the board back of his sketchbook in his pocket keener, as if it had imprinted itself on his skin. He forced himself to slow, to sit down on the saddle, to rehearse his speech in his head. He would greet her as usual, turn the bike around as usual, give her the post for the house and then, just casually, as if it were something extra he’d just remembered, take out his sketchbook, slip out the painting and say to her, ‘This is for you, as a small token of my esteem.’ She would thank him in her solemn voice to show that she took his gift seriously, and would look at it and exclaim to see that it was her favourite view – from Dodd Wood, out over the lake – and perhaps admire the workmanship. Here his stomach made a strange kind of tumble, as if he had swung so high in a swing that he thought he might fly right over the top of the bar. Perhaps she would put it carefully into her camera case and say she would treasure it … The bike jounced into a rut that nearly unseated him. He swerved and squeezed on the brakes; then he took a deep breath and got off the bike, just as she raised her free arm and waved: a wide, expansive gesture that made his heart lift. He forced himself to walk slowly towards her, concentrating on the soft shushing that the tyres made on the drive.

‘Hello there, I don’t suppose you have anything for me?’ she said with a smile as he reached her and swept the bike round in a circle to walk back with her the way he had come.

He handed her the sheaf of letters that he had saved until last. Straightaway she picked out the cream envelope and tucked the rest into her pocket. She felt the letter between her thumb and forefinger and frowned as if surprised by its thinness. She turned it over as if she were about to open it, but then turned it back and started to walk alongside him.

He glanced sideways at her but she didn’t turn to look at him and the words he had planned to say deserted him. ‘Do you have anything to send?’ he asked instead. She shook her head. ‘Nothing from the house today, and I … I’m not sure. Perhaps I should read this one first.’

‘Where are you planning to walk today?’ he asked. ‘It’s very hot once you’re out in the sun, you might find it tiring.’