Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «Take It Back»

KIA ABDULLAH is an author and travel writer. She has contributed to The Guardian, BBC, and Channel 4 News, and most recently The New York Times commenting on a variety of issues affecting the Muslim community. Kia currently travels the world as one half of the travel blog Atlas & Boots, which receives over 200,000 views per month. kiaabdullah.com

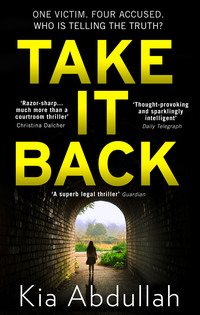

Take It Back

Kia Abdullah

ONE PLACE. MANY STORIES

Copyright

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2019

Copyright © Kia Abdullah 2019

Kia Abdullah asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © August 2019 ISBN: 9780008314699

Note to Readers

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

Change of font size and line height

Change of background and font colours

Change of font

Change justification

Text to speech

Page numbers taken from the following print edition: ISBN 9780008314682

Praise for Take It Back:

‘With razor-sharp insight into the lives of her characters, Kia Abdullah gives readers much more than a courtroom thriller. A timely reminder that the tentacles of scandal are long – and they touch everyone’

Christina Dalcher, Sunday Times bestselling author of VOX

‘Intense, shocking and so real you can literally feel its heartbeat … the best book I’ve read this year’

Lisa Hall, author of Between You and Me and The Party

‘Kia’s novel is an excellent addition to the court-based criminal dramas we’ve come to love. It’s made even more shocking by its basing itself in one of the most challenging environments; rape and diversity. It’s a great read and draws you in with fast pacing and real characters’

Nazir Afzal OBE, Former Chief Crown Prosecutor, CPS

‘I was blown away by Take It Back. From the explosive premise to the shockingly perfect ending, I loved every word’

Roz Watkins, author of The Devil’s Dice

‘Brave and shocking, a real welcome addition to the crime thriller genre. Kia’s is a fresh voice and a thrilling novel’

Alex Khan, author of Bollywood Wives

For Peter

Contents

Cover

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright

Note to Readers

Praise

Dedication

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

EXTRACT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

Chapter One

She watched her reflection in the empty glass bottle as the truth crept in with the wine in her veins. It curled around her stomach and squeezed tight, whispering words that paused before they stung, like a paper cut cutting deep: colourless at first and then vibrant with blood. You are such a fucking cliché, it whispered – an accusation, a statement, a fact. The words stung because Zara Kaleel’s self-image was built on the singular belief that she was different. She was different to the two tribes of women that haunted her youth. She was not a docile housewife, fingers yellowed by turmeric like the quiet heroines of the second-gen literature she hated so much. Nor was she a rebel, using her sexuality to subvert her culture. And yet here she was, lying in freshly stained sheets, skin gleaming with sweat and regret.

Luka’s post-coital pillow talk echoed in her ear: ‘it’s always the religious ones’. She smiled a mirthless smile. The alcohol, the pills, the unholy foreskin – it was all so fucking predictable. Was it even rebellious anymore? Isn’t this what middle-class Muslim kids did on weekends?

Luka’s footsteps in the hall jarred her thoughts. She shook out her long dark hair, parted her lips and threw aside the sheets, secure in the knowledge that it would drive him wild. Women like Zara were never meant to be virgins. It’s little wonder her youth was shrouded in hijab.

He walked in, a climber’s body naked from the waist up, his dirty blond hair lightly tracing a line down his chest. Zara blinked languidly, inviting his touch. He leaned forward and kissed the delicate hollow of her neck, his week-old stubble marking tiny white lines in her skin. A sense of happiness, svelte and ribbon-like, pattered against her chest, searching for a way inside. She fought the sensation as she lay in his arms, her legs wrapped with his like twine.

‘You are something else,’ he said, his light Colorado drawl softer than usual. ‘You’re going to get me into a lot of trouble.’

He was right. She’d probably break his heart, but what did he expect screwing a Muslim girl? She slipped from his embrace and wordlessly reached for her phone, the latest of small but frequent reminders that they could not be more than what they were. She swiped through her phone and read a new message: ‘Can you call when you get a sec?’ She re-read the message then deleted it. Her family, like most, was best loved from afar.

Luka’s hand was on her shoulder, tracing the outline of a light brown birthmark. ‘Shower?’ he asked, the word warm and hopeful between his lips and her skin.

She shook her head. ‘You go ahead. I’ll make coffee.’

He blinked and tried to pinpoint the exact moment he lost her, as if next time he could seize her before she fled too far, distract her perhaps with a stolen kiss or wicked smile. This time, it was already too late. He nodded softly, then stood and walked out.

Zara lay back on her pillow, a trace of victory dancing grimly on her lips. She wrapped her sheets around her, the expensive cream silk suddenly gaudy on her skin. She remembered buying an armful years ago in Selfridges; Black American Express in hand, new money and aspiration thrumming in her heart. Zara Kaleel had been a different person then: hopeful, ambitious, optimistic.

Zara Kaleel had been a planner. In youth, she had mapped her life with the foresight of a shaman. She had known which path to take at every fork in the road, single-mindedly intent on reaching her goals. She finished law school top of her class and secured a place on Bedford Row, the only brown face at her prestigious chambers. She earned six figures and bought a fast car. She dined at Le Gavroche and shopped at Lanvin and bought everything she ever wanted – but was it enough? All her life she was told that if she worked hard and treated people well, she’d get there. No one told her that when she got there, there’d be no there there.

When she lost her father six months after their estrangement, something inside her slid apart. She told herself that it happened all the time: people lost the ones they loved, people were lost and lonely but they battled on. They kept on living and breathing and trying but trite sentiments failed to soothe her anger. She let no one see the way she crumbled inside. She woke the next day and the day after that and every day until, a year later, she was on the cusp of a landmark case. And then, she quit. She recalled the memory through a haze: walking out of chambers, manic smile on her face, feeling like Michael Douglas in Falling Down. She planned to change her life. She planned to change the world. She planned to be extraordinary.

Now, she didn’t plan so much.

It was a few degrees too cold inside Brasserie Chavot, forcing the elegant Friday night crowd into silk scarves and cashmere pashminas. Men in tailored suits bought complicated cocktails for women too gracious to refuse. Zara sat in the centre of the dining room, straight-backed and alone between the glittering chandelier and gleaming mosaic floor. She took a sip from her glass of Syrah, swallowing without tasting, then spotted Safran as he walked through the door.

He cut a path through soft laughter and muted music and greeted her with a smile, his light brown eyes crinkling at the corners. ‘Zar, is that you? Christ, what are you wearing?’

Zara embraced him warmly. His voice made her think of old paper and kindling, a comfort she had long forgotten. ‘They’re just jeans,’ she said. ‘I had to stop pretending I still live in your world.’

‘“Just jeans”?’ he echoed. ‘Come on. For seven years, we pulled all-nighters and not once did you step out of your three-inch heels.’

She shrugged. ‘People change.’

‘You of all people know that’s not true.’ For a moment, he watched her react. ‘You still square your shoulders when you’re getting defensive. It’s always been your tell.’ Without pause for protest, he stripped off his Merino coat and swung it across the red leather chair, the hem skimming the floor. Zara loved that about him. He’d buy the most lavish things, visit the most luxurious places and then treat them with irreverence. The first time he crashed his Aston Martin, he shrugged and said it served him right for being so bloody flash.

He settled into his seat and loosened his tie, a note of amusement bright in his eyes. ‘So, how is the illustrious and distinguished exponent of justice that is Artemis House?’

A smile played on Zara’s lips. ‘Don’t be such a smart-arse,’ she said, only half in jest. She knew what he thought of her work; that Artemis House was noble but also that it clipped her wings. He did not believe that the sexual assault referral centre with its shabby walls and erratic funding was the right place for a barrister, even one who had left the profession.

Safran smiled, his left dimple discernibly deeper than the right. ‘I know I give you a hard time but seriously, Zar, it’s not the same without you. Couldn’t you have waited ’til mid-life to have your crisis?’

‘It’s not a crisis.’

‘Come on, you were one of our strongest advocates and you left for what? To be an evening volunteer?’

Zara frowned. ‘Saf, you know it’s more than that. In chambers, I was on a hamster wheel, working one case while hustling for the next, barely seeing any tangible good, barely even taking breath. Now, I work with victims and can see an actual difference.’ She paused and feigned annoyance. ‘And I’m not a volunteer. They pay me a nominal wage. Plus, I don’t work evenings.’

Safran shook his head. ‘You could have done anything. You really were something else.’

She shrugged. ‘Now I’m something else somewhere else.’

‘But still so sad?’

‘I’m not sad.’ Her reply was too quick, even to her own ears.

He paused for a moment but challenged her no further. ‘Shall we order?’

She picked up the menu, the soft black leather warm and springy on her fingertips. ‘Yes, we shall.’

Safran’s presence was like a balm. His easy success and keen self-awareness was unique among the lawyers she had known – including herself. Like others in the field, she had succumbed to a collective hubris, a self-righteous belief that they were genuinely changing the world. You could hear it dripping from the tones of overstuffed barristers, making demands on embassy doorsteps, barking rhetoric at political figureheads.

Zara’s career at the bar made her feel important, somehow more valid. After a while, the armour and arrogance became part of her personality. The transformation was indiscernible. She woke one day and realised she’d become the person she used to hate – and she had no idea how it had happened. Safran wasn’t like that. He used the acronyms and in-jokes and wore his pinstripes and brogues but he knew it was all for show. He did the devil’s work but somehow retained his soul. At thirty-five, he was five years older than Zara and had helped her navigate the brutal competitiveness of London chambers. He, more than anyone, was struck by her departure twelve months earlier. It was easy now to pretend that she had caved under pressure. She wouldn’t be the first to succumb to the challenges of chambers: the gruelling hours, the relentless pace, the ruthless colleagues and the constant need to cajole, ingratiate, push and persuade. In truth she had thrived under pressure. It was only when it ceased that work lost its colour. Numbed by the loss of her father and their estrangement before it, Zara had simply lost interest. Her wins had lost the glee of victory, her losses fast forgotten. Perhaps, she decided, if she worked more closely with vulnerable women, she would feel like herself again. She couldn’t admit this though, not even to Safran who watched her now in the late June twilight, shifting in her seat, hands restless in her lap.

He leaned forward, elbows on the table. ‘Jokes aside, how are you getting on there?’

Zara measured her words before speaking. ‘It’s everything I thought it would be.’

He took a sip of his drink. ‘I won’t ask if that’s good or bad. What are you working on?’

She grimaced. ‘I’ve got this local girl, a teenager, pregnant by her mother’s boyfriend. He’s a thug through and through. I’m trying to get her out of there.’

Safran swirled his glass on the table, making the ice cubes clink. ‘It sounds very noble. Are you happy?’

She scoffed. ‘Are you?’

He paused momentarily. ‘I think I’m getting there, yeah.’

She narrowed her eyes in doubt. ‘Smart people are never happy. Their expectations are too high.’

‘Then you must be the unhappiest of us all.’ Their eyes locked for a moment. Without elaborating, he changed the subject. ‘So, I have a new one for you.’

She groaned.

‘What do you have if three lawyers are buried up to their necks in cement?’

‘I don’t know. What do I have?’

‘Not enough cement.’

She shook her head, a smile curling at the corner of her lips.

‘Ah, they’re getting better!’ he said.

‘No. I just haven’t heard one in a while.’

Safran laughed and raised his drink. ‘Here’s to you, Zar – boldly going where no high-flying, sane lawyer has ever gone before.’

She raised her glass, threw back her head and drank.

Artemis House on Whitechapel Road was cramped but comfortable and the streets outside echoed with charm. There were no anodyne courtyards teeming with suits, no sand-blasted buildings that gleamed on high. The trust-fund kids in the modern block round the corner were long scared off by the social housing quota. East London was, Zara wryly noted, as multicultural and insular as ever.

Her office was on the fourth floor of a boxy grey building with stark pebbledash walls and seven storeys of uniformly grimy windows. Her fibreboard desk with its oak veneer sat in exactly the wrong spot to catch a breeze in the summer and any heat in the winter. She had tried to move it once but found she could no longer open her office door.

She hunched over her weathered keyboard, arranging words, then rearranging them. Part of her role as an independent sexual violence advisor was filtering out the complicated language that had so long served as her arsenal – not only the legalese but the theatrics and rhetoric. There was no need for it here. Her role at the sexual assault referral centre, or SARC, was to support rape victims and to present the facts clearly and comprehensively so they could be knitted together in language that was easy to digest. Her team worked tirelessly to arch the gap between right and wrong, between the spoken truth and that which lay beneath it. The difference they made was visible, tangible and repeatedly affirmed that Zara had made the right decision in leaving Bedford Row.

Despite this assurance, however, she found it hard to focus. She did good work – she knew that – but her efforts seemed insipidly grey next to those around her, a ragtag group of lawyers, doctors, interpreters and volunteers. Their dedication glowed bright in its quest for truth, flowed tirelessly in the battle for justice. Their lunchtime debates were loud and electric, their collective passion formidable in its strength. In comparison her efforts felt listless and weak, and there was no room for apathy here. She had moved three miles from chambers and found herself in the real East End, a place in which sentiment and emotion were unvarnished by decorum. You couldn’t coast here. There was no shield of bureaucracy, no room for bluff or bluster. Here, there was nothing behind which to hide.

Zara read over the words on the screen, her fingers immobile above the keys. She edited the final line of the letter and saved it to the network. Just as she closed the file, she heard a knock on her door.

Stuart Cook, the centre’s founder, walked in and placed a thin blue folder on her desk. He pulled back a chair and sat down opposite. Despite his unruly blond hair and an eye that looked slightly to the left of where he aimed it, Stuart was a handsome man. At thirty-nine, he had an old-money pedigree and an unwavering desire to help the weak. Those more cynical than he accused him of having a saviour complex but he paid this no attention. He knew his team made a difference to people’s lives and it was only this that mattered. He had met Zara at a conference on diversity and the law, and when she quit he was the first knocking on her door.

He gestured now to the file on her desk. ‘Do you think you can take a look at this for the San Telmo case? Just see if there’s anything to worry about.’

Zara flicked through the file. ‘Of course. When do you need it by?’

He smiled impishly. ‘This afternoon.’

Zara whistled, low and soft. ‘Okay, but I’m going to need coffee.’

‘What am I? The intern?’

She smiled. ‘All I’m saying is I’m going to need coffee.’

‘Fine.’ Stuart stood and tucked the chair beneath the desk. ‘You’re lucky you’re good.’

‘I’m good because I’m good.’

Stuart chuckled and left with thanks. A second later, he stuck his head back in. ‘I forgot to mention: Lisa from the Paddington SARC called. I know you’re not in the pit today but do you think you can take a case? The client is closer to us than them.’

‘Yes, that should be fine.’

‘Great. She – Jodie Wolfe – is coming in to see you at eleven.’

Zara glanced at her watch. ‘Do you know anything about the case?’

Stuart shook his head. ‘Abigail’s sorted it with security and booked the Lincoln meeting room. That’s all I know – sorry.’

‘Okay, thanks. I’ll go over now if it’s free.’ She gestured at the newest pile of paper on her desk. ‘This has got to the tipping point.’

Carefully, she gathered an armful of folders and balanced her laptop on top. Adding a box of tissues to the pile, she gingerly walked to ‘the pit’. This was the central nervous system of Artemis House, the hub in which all clients were received and assigned a caseworker. It was painted a pale yellow – ‘summer meadow’ it had said on the tin – with soft lighting and pastel furnishings. Pictures of lilies and sacks of brightly coloured Indian spices hung on the wall in a not wholly successful attempt to instil a sense of comfort. The air was warm and had the soporific feel of heating left on too long.

Artemis House held not only the sexual assault referral centre but also the Whitechapel Road Legal Centre, both founded with family money. Seven years in, they were beginning to show their lack of funds. The carpet, once a comforting cream, was now a murky beige and the wallpaper curled at the seams. There was a peaty, damp smell in the winter and an overbearing stuffiness in the summer. Still, Zara’s colleagues worked tirelessly and cheerfully. Some, like she, had traded better pay and conditions for something more meaningful.

Zara manoeuvred her way to the Lincoln meeting room, a tiny square carved into a corner of the pit. She carefully set down her armful and divided the folders into different piles: one for cases that had stalled, one for cases that needed action, and another for cases just starting. There she placed Stuart’s latest addition, making a total of twelve ongoing cases. She methodically sorted through each piece of paper, either filing it in a folder or scanning and binning it. She, like most lawyers, hated throwing things away.

She was still sorting through files when half an hour later she heard a gentle knock on the door. She glanced up, taking just a beat too long to respond. ‘May I help you?’

The girl nodded. ‘Yes, I’m Jodie Wolfe. I have an appointment?’

‘Please come in.’ Zara gestured to the sofa, its blue fabric torn in one corner, exposing yellow foam underneath.

The girl said something unintelligible, paused, then tried again. ‘Can I close the door?’

‘Of course.’ Zara’s tone was consciously casual.

The girl lumbered to the sofa and sat carefully down while Zara tried not to stare.

Jodie’s right eye was all but hidden by a sac of excess skin hanging from her forehead. Her nose, unnaturally small in height, sat above a set of puffy lips and her chin slid off her jawline in heavy folds of skin.

‘It’s okay,’ misshapen words from her misshapen mouth. ‘I’m used to it.’ Dressed in a black hoodie and formless blue jeans, she sat awkwardly on the sofa.

Zara felt a heavy tug of pity, like one might feel for a bird with a broken wing. She took a seat opposite and spoke evenly, not wanting to infantilise her. ‘Jodie, let’s start with why you’re here.’

The girl wiped a corner of her mouth. ‘Okay but, please, if you don’t understand something I say, please ask me to repeat it.’ She pointed at her face. ‘Sometimes it’s difficult to form the words.’

‘Thank you, I will.’ Zara reached for her notepad. ‘Take your time.’

The girl was quiet for a moment. Then, in a voice that was soft and papery, said, ‘Five days ago, I was raped.’

Zara’s expression was inscrutable.

Jodie searched for a reaction. ‘You don’t believe me,’ she said, more a statement than a question.

Zara frowned. ‘Is there a reason I shouldn’t?’

The girl curled her hands into fists. ‘No,’ she replied.

‘Then I believe you.’ Zara watched the tension ease. ‘Can I ask how old you are?’

‘Sixteen.’

‘Have you spoken to anyone about this?’

‘Just my mum.’ She shifted in her seat. ‘I haven’t told the police.’

Zara nodded. ‘You don’t have to make that decision now. What we can do is take some evidence and send it to the police later if you decide you want to. We will need to take some details but you don’t have to tell me everything.’

Jodie pulled at the cuffs of her sleeves and wrapped them around her fingers. ‘I’d like to. I think I might need to.’

Zara studied the girl’s face. ‘I understand,’ she said, knowing that nerve was like a violin string: tautest just before it broke. If Jodie didn’t speak now, she may never find the courage. She allowed her to start when ready, knowing that victims should set their own pace and use pause and silence to fortify strength.

Jodie began to speak, her voice pulled thin by nerves, ‘It was Thursday just gone. I was at a party. My first ever one. My mum thought I was staying at my friend Nina’s house. She’s basically the daughter Mum wished she had.’ There was no bitterness in Jodie’s tone, just a quiet sadness.

‘Nina made me wear these low-rise jeans and I just felt so stupid. She wanted to put lipstick on me but I said no. I didn’t want anyone to see that I was … trying.’ Jodie squirmed with embarrassment. ‘We arrived just after ten. I remember because Nina said any earlier and we’d look desperate. The music was so loud. Nina’s always found it easy to make friends. I’ve never known why she chose me to be close to. I didn’t want to tag along with her all evening – she’s told me off about that before – so I tried to talk to a few people.’ Jodie met Zara’s gaze. ‘Do you know how hard that is?’

Zara thought of all the corporate parties she had attended alone; how keen she had been for a friend – but then she looked at Jodie’s startling face and saw that her answer was, ‘no’. Actually, she didn’t know how hard it was.

Jodie continued, ‘Nina was dancing with this guy, all close. I couldn’t face the party without her, so I went outside to the park round the back.’ She paused. ‘I heard him before I saw him. His footsteps were unsteady from drinking. Amir Rabbani. He—he’s got these light eyes that everyone loves. He’s the only boy who hasn’t fallen for Nina.’

Zara noted the glazed look in Jodie’s eyes, the events of that night rendered vivid in her mind.

Jodie swallowed. ‘He came and sat next to me and looked me in the eye, which boys never do unless they’re shouting ugly things at me.’ She gave a plaintive smile. ‘He reached out and traced one of my nails with his finger and I remember thinking at least my hands are normal. Thank you, God, for making my hands normal.’ Jodie made a strangled sound: part cry and part scoff, embarrassed by her naivety. ‘He said I should wear lace more often because it makes me look pretty and—’. Her gaze dipped low. ‘I believed him.’

Jodie reached for a tissue but didn’t use it, twisting it in her hands instead. ‘He said, “I know you won’t believe me but you have beautiful lips and whenever I see you, I wonder what it would be like to kiss you.”’ Jodie paused to steady her voice. ‘He asked if I would go somewhere secret with him so he could find out what it was like. I’ve never known what it’s like to be beautiful but in that moment I got a taste and …’ Jodie’s eyes brimmed with tears. ‘I followed him.’ She blinked them back through the sting of shame.

Zara smarted as she watched, dismayed that Jodie had been made to feel that way: to believe that her value as a young woman lay in being desirable, but that to desire was somehow evil.

Jodie kneaded the tissue in her fingers. ‘He led me through the estate to an empty building. I was scared because there were cobwebs everywhere but he told me not to worry. He took me upstairs. We were looking out the window when …’ Jodie flushed. ‘He asked me what my breasts were like. I remember feeling light-headed, like I could hear my own heart beating. Then he said, “I ain’t gonna touch ’em if they’re ugly like the rest of you.”’ Jodie’s voice cracked just a little – a hairline fracture hiding vast injury.

Zara watched her struggle with the weight of her words and try for a way to carry them, as if switching one for another or rounding a certain vowel may somehow ease her horror.

Jodie’s voice grew a semitone higher, the tissue now balled in her fist. ‘Before I could react, his friends came out of the room next door. Hassan said, “This is what you bring us?” and Amir said he chose me because I wouldn’t tell anyone. Hassan said, “Yeah, neither would a dog.”’

Jodie gripped her knee, each finger pressing a little black pool in the fabric of her jeans. Her left foot tap-tapped on the floor as if working to a secret beat. ‘Amir said, “She’s got a pussy, don’t she?” and told me to get on my knees. I didn’t understand what was happening. I said no. He tried to persuade me but I kept saying no …’ Jodie exhaled sharply, her mouth forming a small O as if she were blowing on tea. ‘He—he told his friends to hold me.’

Zara blinked. ‘How many were there?’ she asked softly.

Jodie shifted in her seat. ‘Four. Amir and Hassan and Mo and Farid.’

Zara frowned. ‘Do you know their surnames?’

‘Yes. Amir Rabbani, Hassan Tanweer, Mohammed Ahmed and Farid Khan.’

Zara stiffened. A bead of sweat trickled down the small of her back. Four Muslim boys. Four Muslim boys had raped a disabled white girl.

‘I—’ Jodie faltered. ‘I wasn’t going to tell anyone because …’ her voice trailed off.

‘You can tell me.’ Zara reached out and touched the girl’s hand. It was an awkward gesture but it seemed to soothe her.

‘Because if a month ago, you had told me that any one of those boys wanted me, I would have thought it was a dream come true.’ Hot tears of humiliation pooled in her eyes. ‘Please don’t tell anyone I said that.’

A flush of pity bloomed on Zara’s cheeks. ‘I won’t,’ she promised.

Jodie pushed her palms beneath her thighs to stop her hands from shaking. ‘Farid said he wasn’t going to touch a freak like me so Hassan grabbed me and pushed me against the wall. He’s so small, I thought I could fight him but he was like an animal.’ Jodie took a short, sharp breath as if it might stifle her tears. ‘Amir said he would hurt me if I bit him and then he … he put himself in my mouth.’ Jodie’s lips curled in livid disgust. ‘He grabbed my hair and used it to move my head. I gagged and he pulled out. He said he didn’t want me to throw up all over him and …’ A sob rose from her chest and she held it in her mouth with a knuckle. ‘He finished himself off over me.’