Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «Faith»

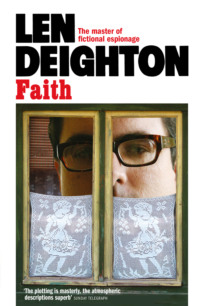

Cover designer’s note

As Bernard Samson is now on an assignment in Poland I searched through my collection of photographs for a suitable image that would evoke that part of the world, and Bernard’s involvement with the women in his life.

I remembered that, while on location for one of my documentaries in Poland, I had come across a window with a lace curtain adorned with a pair of ladies; the image of this would now provide a subtle visual analogy for the Iron Curtain.

I discovered that by placing a larger than life photograph of Samson in the window it created a rather surreal effect. Rather like Kong peering in at an unsuspecting Fay Wray, Bernard looms behind the curtain, an unwilling outsider ostracized from domestic comfort.

For a further reference to the two women in Bernard’s life, the back cover displays a heart-shaped traditional Polish Wycinanki, an intricate design carefully cut from folded paper. Here, the heart is torn in two, separated by the sword of a KGB badge. You will note that the Western half features a very elegant gold wedding ring.

At the heart of every one of the nine books in this triple trilogy is Bernard Samson, so I wanted to come up with a neat way of visually linking them all. When the reader has collected all nine books and displays them together in sequential order, the books’ spines will spell out Samson’s name in the form of a blackmail note made up of airline baggage tags. The tags were drawn from my personal collection, and are colourful testimony to thousands of air miles spent travelling the world.

Arnold Schwartzman OBE RDI

Len Deighton

Faith

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1994

FAITH. Copyright © Len Deighton 1994.

Introduction copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 2011

Cover designer’s note © Arnold Schwartzman 2011

Len Deighton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007395743

Ebook Edition © JUNE 2011 ISBN: 9780007395781

Version: 2018-07-31

Contents

Cover designer’s note

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

1

‘Don’t miss your plane, Bernard. This whole operation depends upon…

2

Magdeburg, where we were headed, is one of the most…

3

‘I have your report,’ said Frank Harrington. ‘I read it…

4

‘You just leave it to me, Mr Samson,’ said the…

5

There was a time when Zurich was my back yard.

6

‘So – here is pain?’ I felt the dental probe…

7

Fiona loved to go to bed ridiculously early and then…

8

Dicky arrived at work only thirty minutes after I did.

9

On Tuesday morning, as if to confirm Gloria’s theory –…

10

Those grey and stormy days were, like my life, punctuated…

11

I’ve often suspected that my father-in-law had sold his soul…

12

I ordered a car to collect me from the office…

13

‘Your new hair-do looks nice, Tante Lisl,’ I said, in…

14

Whatever trauma may have been troubling the deeper recesses of…

15

I don’t know how long it was before I was…

16

Had I persisted with my plan to return to the…

17

I often thought that Daphne’s life with Dicky must have…

18

When we were driving home from the Cruyers’ that Saturday…

19

I got to the office a few minutes before eleven.

20

Werner went back to Berlin and began making all the…

21

‘Why have you got all this paper in your office?’…

Keep Reading

About the Author

Other Books by Len Deighton

About the Publisher

Introduction

‘Is this going to go into a book, Len?’ my friend asked. He was a close and trusted friend and also an important functionary of the communist government. But he was armed with a healthy scepticism for all authority and this provided a bond and, at times, much merriment. I can’t remember which year it was; sometime in the mid-nineteen sixties probably. We were sitting on a bench in what had once been the site of the Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp near Berlin.

‘I don’t know,’ I replied.

‘Because when I read your books I suddenly come across a description of something we have seen or done together and it brings it all back to me.’

To write these introductions I have been reading my books and this has revived many memories. Some memories have been happy ones but some are painful and now and again I have had to put the book aside for a moment or two. It is only now, with this re-reading, that I see how much of what I wrote was based on people, facts and experiences. I have often claimed that my books were almost entirely created from my imagination but now I see that this was something of a delusion. Now, as I read and recall events half-forgotten, brave people and strange places come crowding into my memory. Many of these people and places no longer exist. I can’t offer you the past world but here is a depiction of it; here are my impressions of that world as I recorded it.

I had asked my friend to take me to the Sachsenhausen site, which was in the ‘Zone’ thirty miles from Berlin and outside the limits of its Soviet Sector. We went in his ancient Wartburg car with its noisy two-stroke engine that left a trail of smoke and envy. For even this contraption represented luxury to the average citizen in the East. Since neither of us had permission to enter the Zone we enjoyed the childish thrill of breaking the law. Sachsenhausen had been the Concentration Camp nearest to Berlin, and for that reason it was haunted by the ghosts of Hitler’s specially selected victims. Eminent German generals had been locked up here before being tortured and executed for participation in the ‘July 20th’ attempt to overthrow the Führer. Some notable British agents passed through these bloodstained huts including Best and Stevens, who were senior SIS agents and whose capture and interrogation crippled the British Secret Intelligence Service for the whole war. Peter Churchill, an agent of the British SOE, was brought here. Martin Niemoller was imprisoned here too, so was Josef Stalin’s son and Bismarck’s grandson. Paul Reynaud, the PM of France, the prominent former Reichstag member Fritz Thyssen, Kurt Schuschnigg the Austrian chancellor and countless other anti-Nazis were locked away here. So were the Prisoners of War who escaped from Colditz, German Trade Union leaders, Jews and anyone who stepped out of line.

The camp had been set up in 1933 by Hitler’s brown-shirted hooligans, the Sturmabteilung, but the ‘Night of the Long Knives’ had seen fortunes reversed; the SA leaders were murdered by Himmler’s SS ‘Death’s Head’ units, which took control of the camps and of much else. It was while under SS control that the camp installed a forgery unit for Operation Bernhard, for which imprisoned printing and engraving experts were sought from camps far and wide. These prisoners forged documents of many kinds and produced counterfeit currency – notably British five-pound notes – that even the Swiss bankers could not distinguish from the authentic ones. But more horribly, this camp was notorious for the systematic murder by gassing of many thousands of innocent Jews. My friend, in an official capacity, had interrogated one of the camp’s Nazi commanders during his postwar captivity, and recalled the chilling way in which he had spoken of the killings without remorse or regret.

After the war, the Sachsenhausen camp was used by the Russians. Called ‘Special Camp No. 1’, they imprisoned here anyone they considered to be enemies of the Soviet occupation authorities or anyone who opposed the communist system of totalitarian government. After the Wall fell, and the Russians departed, excavations revealed more than 12,000 bodies of people who died during the period of Soviet control.

In fact, I never did use my visit to the Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg camp complex in my books but it was another lesson in my attempt to understand Germany and the Germans. German history has always obsessed me and in my writing a well-researched historical background provides a necessary dimension to the Berlin where Bernard Samson has lived since childhood. Although my asides about German history are subordinate to the plot and to the characterizations, they are researched with care and attention. And the story is not confined to Berlin. Faith quickly moves into Magdeburg, which the German secret police and their Russian colleagues made the centre of their operations. My brief aside about Adolf Hitler’s mortal remains being held there was based upon reliable evidence. Despite what is widely written, Hitler’s body was not completely consumed by flame in a shallow trench outside the Berlin bunker. The amount of gasoline used could not ignite a fresh corpse, so much of which is water. When the Soviet Russian Army arrived in Berlin, the army’s secret police seized what remained of Hitler’s body as a macabre trophy, and have held on to it ever since. After Magdeburg this collection of dried flesh and scorched bone was taken to Moscow where, as far as my research can discover, it remains, kept in a glass-sided cabinet like the revered body fragments of medieval saints.

Discovering facts or a sequence of events that others have missed is the great joy of research. Some such discoveries can be confirmed given a little digging, some cross-references and some whispered confidences. Even such well-turned over soil as the Battle of Britain revealed to me some remarkable revelations and in Fighter became a cause of argument and anger. Now, however, the ‘surprises’ in my history books have been accepted as facts. But some research brings surprises more difficult to confirm. Even when I am quite sure about the truth of them I have abstained from declaring them as history. But ‘fiction’ brings an opportunity to say things that are difficult to prove. That’s how it stands with the revelations about the Russian Army’s electronics and hardware being stolen and shipped from Poland in exchange for CIA money. There were historical finds, too. I discovered that, during the Nazi regime, all extermination camps were situated just outside the German border so that the insurance companies could avoid payment to the relatives of people murdered in the camps, but I failed to find written evidence. Other than the maps that showed how deliberately systematic the siting of the camps was, proof was beyond me. My recourse was to use that undoubtedly true discovery in Winter together with other lesser-known facts of history.

I work hard to make each book of the Samson series complete, and I contrive a story that does not depend on knowledge of the other books. The story of Faith continues directly from Sinker, which is devoted mainly to the events seen through the eyes of Bernard’s wife, Fiona. Fiona’s secret assignment was to establish financial links between London and the Lutheran Church in the German Democratic Republic, i.e. communist Germany. It was an important task and a notable success. Of the 20 million people living in communist East Germany about ninety per cent remained members of the Christian Church. As Bret remarks, they provided a ‘powerful cohesive force’ that would eventually break down the Wall.

But the plot, and the strategy of the British intelligence service, is not the most important thread in the series. The characters were at the heart of my labours. The social exchanges of Faith demonstrate Bernard’s painful dilemma when Fiona confronts Gloria, and the love affair which Bernard stumbles into when he believes that he will never see his wife again. The reactions of both women, and such events as Dicky Cruyer’s dinner party which both women attend, is vital to the development of the plot and the interaction between all the major characters.

Writing ten books about the same small group of people is a strange and demanding task. I am a slow worker and I don’t take regular vacations or set work aside for prolonged periods. Ten books meant about fifteen years during which these people, their hopes and fears and loves and betrayals were constantly whirling around in my brain. They disturbed my sleep and invaded my dreams in a way I did not always enjoy. Because the story line was such a long one, the characters became well-defined and were not easily bent to the needs of the plot. Unlike the content of my other books, Bernard Samson and his circle became imprinted in my mind and remain there today. I confess to you that I find this unremitting concern for these fictional people disturbing. That long period of concentration seemed to be a brain-washing. Do other writers suffer the same problems? I don’t know; not many writers produce ten books about the same people so it is not easy to find out.

Len Deighton, 2011

1

‘Don’t miss your plane, Bernard. This whole operation depends upon the timing.’ Bret Rensselaer peered around to spot a departures indicator; but this was Los Angeles airport and there were none in sight. They would spoil the architect’s concept.

‘It’s okay, Bret,’ I said. He would never have survived five minutes as a field agent. Even when he was my boss, driving a desk at London Central, he’d been like this: repeating the instructions, wetting his lips, dancing from one foot to the other and furrowing his brow as if goading his memory.

‘Just because Comrade Gorbachev is kissing Mrs Thatcher and spreading that glasnost schmaltz in Moscow, it doesn’t mean those East German bastards are buying any of it. Everything we hear says the same thing: they are more stubborn and vindictive than ever.’

‘It will be just like home,’ I said.

Bret sighed. ‘Try and see it from London’s point of view,’ he said with exaggerated patience. ‘Your task was to bring Fiona across the wire as quickly and quietly as possible. But you fixed it so your farewell performance out on that Autobahn was like the last act of Hamlet. You shoot two bystanders, and your own sister-in-law gets killed in the crossfire.’ He glanced at my wife Fiona, who was still recovering from seeing her sister Tessa killed. ‘Don’t expect London Central to be waiting for you with a gold medal, Bernard.’

He’d bent the facts but what was the use of arguing? He was in one of his bellicose moods, and I knew them well. Bret Rensselaer was a slim American who’d aged like a rare wine: growing thinner, more elegant, more subtle and more complex with every year that passed. He looked at me as if expecting some hot-tempered reaction to his words. Getting none, he looked at my wife. She was older too, but no less serene and beautiful. With that face, her wide cheekbones, flawless complexion and luminous eyes, she held me in thrall as she always had done. You might have thought that she was completely recovered from her ordeal in Germany. She was gazing at me with love and devotion and there was no sign she’d heard Bret.

Sending me to do this job in Magdeburg was not Bret’s idea. I’d caught sight of the signal he sent to London Central telling them that I was no longer suited to field work, particularly in East Germany. He’d asked them to chain me to a desk until pension time rolled round. It sounded considerate, but I wasn’t pleased. I needed to do something that would put me back in Operations; that was my only chance of being promoted and getting a senior staff position in London. Unless my position improved I would wind up with a premature retirement and a pension that wouldn’t pay for a cardboard box to live in.

I nodded. Bret always observed the niceties of hospitality. He had driven us to Los Angeles airport through a winter rainstorm to say goodbye. They could watch me climb on to the plane bound for Berlin, and my assignment. Then he would put Fiona on the direct flight to London. The Wall was still there and people were getting killed while climbing over it. Now Bret was just repeating all the things he’d told me a thousand times before, the way people do when they are saying goodbye at airports.

‘Keep the faith,’ said Bret, and in response to my blank look he added: ‘I’m not talking about timetables or statistics or training manuals. Faith. It’s not in here.’ He tapped his forehead. ‘It’s in here.’ Gently he thumped his heart with a flattened palm so that the signet ring glittered on his beautifully manicured hand, and a gold watch peeped out from behind a starched linen cuff.

‘Yes, I see. Not a headache; more like indigestion,’ I said. Fiona watched us and smiled.

‘They are calling the flight,’ said Bret.

‘Take care, darling,’ she said. I took Fiona in my arms and we kissed decorously, but then I felt a sudden pain as she bit my lip. I gave a little yelp and stepped back from her. She smiled again. Bret looked anxiously from me to Fiona and then back at me again, trying to decide whether he should smile or say something. I rubbed my lip. Bret concluded that perhaps it was none of his business after all, and from his raincoat pocket he brought a shiny red paper bag and gave it to me. It was secured with matching ribbon tied in a fancy gift-wrap bow. The package was slightly limp; like a paperback book.

‘Read that,’ said Bret, picking up my carry-on bag and shepherding me towards the gate where the other passengers were standing in line. It seemed as if it would be a full load today; there were women with crying babies and long-haired kids with earrings, well-used backpacks and the sort of embroidered jackets that you can buy in Nepal. Fiona followed, observing the people crowding round us with that detached amusement with which she cruised through life. With one phone call Bret could have arranged for us to use any of the VIP lounges on the airport, but the Department’s guidelines said that agents travelling on duty kept to a low profile, and so that’s what Bret did. That’s why he’d left his driver behind at the house and taken the wheel of the Accord. Like other Americans before him, he had exaggerated respect for what the people in London thought was the right way to do things. We reached the gate. I couldn’t go through until he handed over my carry-on bag.

‘Maybe all this hurry-hurry from London will work out for the best, Bernard. Your few days chasing around East Germany will give Fiona a chance to get your London apartment ready. She wants to do that for you. She wants to settle down and start all over again.’ He looked at her and waited until she nodded agreement.

Only Bret would have the chutzpah to explain my wife to me while she was standing beside him. ‘Yes, Bret,’ I said. There was no sense in telling him he was out of line. Another few minutes and I’d be rid of him for ever.

‘And don’t go chasing after Werner Volkmann.’

‘No,’ I said.

‘Don’t give me that glib no-of-course-not routine. I mean it. Whatever Werner did to them, London Central hate him with a passion beyond compare.’

‘Yes, you told me that.’

‘You can’t afford to step out of line, Bernard. If someone spots you having a cup of coffee with your old buddy Werner, everyone in London will be saying you are part of a conspiracy or something. God knows what he did to them but they hate him.’

‘I wouldn’t know where to find him,’ I said.

‘That’s never stopped you before.’ Bret paused and looked at his watch. ‘Be a model employee. Put your faith in the Department, Bernard. Swallow your pride and tug your forelock. Now that London Central’s funds are being so severely cut, they are looking for an excuse to fire people instead of retire them. No one’s job is safe.’

‘I’ve got it all, Bret,’ I said, and tried to prise my bag away from him.

He smiled and moistened his lips, as if trying to resist giving me any more advice and reminders. ‘I hear Tante Lisl has had a check-up. If she’s going to have a hip replacement, or whatever it is, trying to save a few bucks on it is dumb.’

That was his way of saying that he’d pay old Frau Hennig’s doctor’s bills. I knew Bret well. We’d had our ups and downs, especially when I thought he was chasing Fiona, but I’d got to know him better during my long stay in California. As far as I could tell, Bret wasn’t a double-crosser. He didn’t lie or cheat or steal except when ordered to do so, and that put him into a very tiny minority of the people I worked with. He handed over my bag and we shook hands. We were out of earshot of Fiona and anyone else.

‘This Russkie who’s asking for you, Bernard,’ he whispered. ‘He says he owes you a favour, a big favour.’

‘So you said.’

‘VERDI: that’s his codename of course.’ I nodded solemnly. I’m glad Bret told me that or I might have arrived expecting an aria from La Traviata. ‘A colonel,’ he coaxed me. ‘His father was a junior lieutenant with one of the first Red Army units to enter Berlin in April ’45 and stayed there to become a staff officer at Red Army headquarters, on long-term political assignment at Berlin-Karlshorst. Dad married a pretty German fräulein, and VERDI grew up more German than Russian … so the KGB grabbed him. Now he’s a colonel and wants a deal.’ Having gabbled his way through this description he paused. ‘And you still can’t guess who he might be?’ Bret looked at me. Surely he knew I wasn’t going to start that kind of game; it would open a can of worms that I wanted to keep tightly shut.

‘Do you have any idea how many hustlers out there answer that kind of description?’ I said. ‘They all have stories like that. Seems like those first few Ivans into town fathered half the population of the city.’

‘That’s right. Play it close to the chest,’ said Bret. ‘That’s always been your way, hasn’t it?’ He so wanted to be in London, and be a part of it again, that he actually envied me. It was almost laughable. Poor old Bret was past it; even his friends said that.

‘And your girlfriend,’ whispered Bret. ‘Gloria. Make sure that’s all over and done with.’ His voice was edged with the indignant anger that we all feel for other men’s philandering. ‘Try to hang on to both of them and you’ll lose Fiona and the children. And maybe your job too.’

I smiled mirthlessly. The airline girl ripped my boarding pass in half and before I went down the jetty I turned back to wave to them. Who would have guessed that my wife was a revered heroine of the Secret Intelligence Service? And with every chance of becoming its Director-General, if Bret’s opinion was anything to go by. At this moment Fiona looked like a photo from some English society magazine. Her old Burberry coat, its collar turned up to frame her head, and a colourful Hermès scarf knotted at the point of her chin, made her look like an English upper-class mum watching her children at a gymkhana. She held a handkerchief to her face as if about to cry, but it was probably the head cold she’d had for a week and couldn’t shake off. Bret was standing there in his short black raincoat; as still and expressionless as a stone statue. His fair hair was now mostly white and his face grey. And he was looking at me as if imprinting this moment on his memory; as if he was never going to see me again.

As I walked down the enclosed jetty towards the plane a series of scratched plastic windows, rippling with water, provided a glimpse of rain-lashed palm trees, lustrous engine cowling, sleek tailplane and a slice of fuselage. Rain was glazing the jumbo, making its paintwork shiny like a huge new toy; it was a hell of a way to say goodbye to California.

‘First Class?’

Airlines arrange things as if they didn’t want you to discover that you were boarding a plane, so they wind up with something like a cramped roadside diner that smells of cold coffee and stale perspiration and has exits on both sides of the ocean.

‘No,’ I said. ‘Business.’ She let me find my own assigned place. I put my carry-on bag into the overhead locker, selected a German newspaper from the display and settled into my seat. I looked out of the tiny window to see if Bret was pressing his nose against the window of the departure lounge but there was no sign of him. So I settled back and opened the red bag that contained his going-away present. It was a Holy Bible. Its pages had gold edges and its binding was of soft tooled leather. It looked very old. I wondered if it was some sort of Rensselaer family heirloom.

‘Hi there, Bernard.’ A man named ‘Tiny’ Timmermann called to me from his seat across the aisle. A linguist of indeterminate national origins – Danish maybe – he was a baby-faced 250-pound wrestler, with piggy eyes, close-cropped skull and heavy gold jewellery. I knew him from Berlin in the old days when he was some kind of well-paid consultant to the US State Department. There was a persistent rumour that he’d strangled a Russian ship’s captain in Riga and brought back to Washington a boxful of manifests and documents that gave details of the nuclear dumping the Russian Navy was doing into the sea off Archangel. Whatever he’d done for them, the Americans always seemed to treat him generously, but now, the rumours said, even Tiny’s services were for hire.

‘Good to see you, Tiny,’ I said.

‘Hals und Beinbruch!’ he said, wishing me good fortune as if dispatching me down a particularly hazardous ski-run. It shook me. Did he guess I was on an assignment? And if news of it had reached Tiny who else knew?

I gave him a bemused smile and then we were strapping in and the flight attendant was pretending to blow into a life-vest, and after that Tiny produced a lap-top computer from his case and started playing tunes on it as if to indicate that he wasn’t in the mood for conversation.

The plane had thundered into the sky, banked briefly over the Pacific Ocean and set course northeast. I stretched out my legs to their full Business Class extent and opened my newspaper. At the bottom of the front page a discreet headline, ‘Erich Honecker proclaims Wall will still exist in 100 years,’ was accompanied by a smudgy photo of him. This optimistic expressed view of the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the SED, the party governing East Germany, seemed like the sincere words of a dedicated tyrant. I believed him.

I didn’t read on. The newsprint was small and the grey daylight was not much helped by my dim overhead reading light. Also my hand trembled as it held the paper. I told myself that it was a natural condition arising from the rush to the airport and carrying a ton of baggage from the car while Bret fought off the traffic cops. Putting the newspaper down I opened the Bible instead. There was a yellow sticker in a page marking a passage from St Luke:

For I tell you, that many prophets and kings have desired to see those things which ye see, and have not seen them; and to hear those things which ye hear, and have not heard them.

Yes, very droll, Bret. The only inscription on the flyleaf was a pencilled scrawl that said in German, ‘A promise is a promise!’ It was not Bret’s handwriting. I opened the Bible at random and read passages but I kept recalling Bret’s face. Was it his imminent demise I saw written there? Or his anticipation of mine? Then I found the letter from Bret. One sheet of thin onion-skin paper, folded and creased so tightly that it made no bulge in the pages.

‘Forget what happened. You are off on a new adventure,’ Bret had written in that loopy coiled style that characterizes American script. ‘Like Kim about to leave his father for the Grand Trunk Road, or Huck Finn starting his journey down the Mississippi, or Jim Hawkins being invited to sail to the Spanish Caribbean, you are starting all over again, Bernard. Put the past behind you. This time it will all be different, providing you tackle it that way.’

I read it twice, looking for a code or a hidden message, but I shouldn’t have bothered. It was pure Bret right down to the literary clichés and flowery good wishes and encouragement. But it didn’t reassure me. Kim was an orphan and these were all fictional characters he was comparing me with. I had the feeling that these promised beginnings in distant lands were Bret’s way of making his goodbye really final. It didn’t say: come back soon.

Or was Bret’s message about me and Fiona, about our starting our marriage anew? Fiona’s pretended defection to the East was being measured by the valuable encouragement she’d given to the Church in its opposition to the communists. Only I could see the price she had paid. In the last couple of weeks she’d been confident and more vivacious than I could remember her being for a very long time. Of course she was never again going to be like the Fiona I’d first met, that eager young Oxford-educated adventurer who had crewed an oceangoing yacht and could argue dialectical materialism in almost perfect French while cooking a souffle. But if she was not the same person she’d once been, then neither was I. No one could be blamed for that. We’d chosen to deal in secrets. And if her secret task had been so secret that it had been kept concealed even from me then I would have to learn not to resent that exclusion.