Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «She Was the Quiet One»

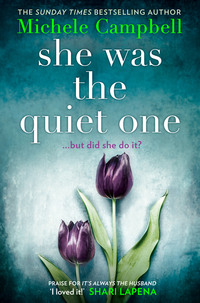

MICHELE CAMPBELL is a graduate of Harvard University and Stanford Law School. She worked at a prestigious Manhattan law firm before spending eight years fighting crime in NYC as a federal prosecutor. Her debut novel It’s Always The Husband was a Sunday Times top ten bestseller.

Copyright

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2019

Copyright © Michele Rebecca Martinez Campbell 2019

Michele Campbell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © January 2019 ISBN: 9780008301828

Praise for Michele Campbell

‘A page-turning whodunnit that will speak to anyone who’s ever had a frenemy.’

Ruth Ware

‘A gripping, tangled web of a novel – it pulls you in and doesn’t let you go. I loved it!

Shari Lapena

‘Secrets and scandals in an ivy league setting. What could be more riveting?’

Tess Gerritsen

‘A skillful and addictive story of friendship, betrayal and ultimately love, It’s Always The Husband will keep you turning the pages until its dramatic end.’

B A Paris

‘A brilliantly layered, utterly compelling, clever mystery story that crackles with poisoned friendships and dirty secrets… Twisted, shocking and sharply observed. It’s Always The Husband has blockbuster movie written all over it!’

Samantha King

‘A gripping page-turner…will suit fans of Liane Moriarty.’

Hello!

‘Readers will… be drawn in to the novel’s intricate exploration of divided loyalties and the brittleness of trust.’

Publishers Weekly

For Meg

The only quiet woman is a dead one.

—SYLVIA PLATH

Contents

Cover

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

Epigraph

part one

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

part two

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Coming Soon

Extract

About the Publisher

part

one

1

February

They locked her in the infirmary and took away her phone and anything she might use to harm herself—or someone else. The school didn’t tout this in its glossy brochures, but that’s how it handled kids suspected of breaking the rules. Lock them in the infirmary, isolate them, interrogate them until they crack. Usually you got locked up for cheating on a test or smoking weed in the woods. In the worst-case scenario, hazing. Not murder.

She lay on the narrow bed and stared at the ceiling. They’d given her sedatives at first, and then something for the pain. But her head still pounded, and her mind was restless and foggy all at once. A large lump protruded from the back of her skull. She explored it with her fingers, trying to remember what had caused it. At the edge of her consciousness, something terrible stirred, and she pushed it away. If she turned off the light, she would see it, that thing at the edge of the lake.

That thing. Her sister. Her twin.

All across campus on this cold, dead night, silence reigned. She was being accused of a terrible crime, and there was nobody to speak in her defense. They’d called her grandmother to come defend her. But her grandmother believed she was guilty. Even her closest friends suspected her, and she had to admit, they had reason to. She and her sister were close once, but this awful school had changed that. They’d come to doubt each other, to talk behind each other’s backs, to rat on each other for crimes large and small, to steal from one another. Mere days earlier, they’d gotten into a physical fight so intense that the girl who interceded wound up with a black eye. That girl hadn’t told—yet. But she would now.

It wasn’t fair. Just because they’d had a fight didn’t mean she would kill her sister. How could she? Her sister was the only family she had left. Everybody else had died, or abandoned her. Why would she hurt her only family, her only friend? But every time she closed her eyes, she saw the blood on her hands, the stab wounds, the long hair fanned out. Her sister’s face, white and still in the moonlight. She was there when it happened. Why? It couldn’t be because she was the killer. That wasn’t true. She was innocent. She knew it in her heart.

But nobody believed her.

2

The September Before

Sarah Donovan was a bundle of nerves as she fed her kids a rushed breakfast of instant oatmeal and apple juice. Four-year-old Harper and two-year-old Scottie were still in their pajamas, their good clothes hidden away among half-unpacked boxes. Today was opening day at Odell Academy, the prestigious old boarding school in New Hampshire, and Sarah and her husband, Heath, had just been appointed the dorm heads of Moreland Hall. They’d been laboring in the trenches as teachers for the past five years, and this new job was a vote of confidence, a step up into the school’s administration. It came with a raise and faculty housing and the promise of more to come. Sarah ought to be thrilled. Heath certainly was. Yet she couldn’t shake a sneaking feeling of dread.

“Hurry up, sweetie, two more bites,” Sarah said to Scottie, who sat in his high chair playing with his food, a solemn expression on his funny little face. Scottie was like Sarah—quiet, observant, a worrier, with a lot going on behind his eyes—whereas Harper was an open book. She met life head-on, ready to dominate it, just like her dad.

“If you’re done, Harps, go brush your teeth.”

“Mommy, I’m gonna wear my party dress,” Harper announced as she climbed down from her booster seat. She was beautiful, and she knew it, with big blue eyes and wild mane of curls, and she loved to dress up and show off.

“You have to find it first. Look in the box next to your bed.”

Harper ran off, and Sarah glanced at the clock. They had a half hour till the students and their families began to arrive. Sarah had spent the afternoon yesterday preparing for the welcome reception, and as far as refreshments and party supplies were concerned, she was all set. Five large boxes from Dunkin’ Donuts sat on the kitchen counter, along with multiple half gallons of apple cider and lemonade, napkins and paper plates, party decorations and name tags. All that remained was to move everything to the Moreland common room and plaster a smile on her face. So why was she so nervous?

Maybe because the stakes were so high. Heath and Sarah had been brought in to clean up Moreland Hall’s unsavory reputation, and the task was daunting. Bad behavior happened all over Odell’s campus, but it happened most often in Moreland. Sarah thought it must have something to do with the fact that a disproportionate share of Moreland girls came from old Odell families. (Moreland had been the first dorm at Odell to house girls when the school went coed fifty years before, and alumni kids often requested to live in the same dorms their parents had.) Sarah had nothing against legacy students per se. She was one herself, having graduated from Odell following in the footsteps of her mother, her father, aunts, uncles and a motley array of cousins. But she couldn’t deny that some legacy kids were spoiled rotten, and Moreland legacies notorious among them.

At the end of the last school year, two Moreland seniors made national news when they got arrested for selling drugs. The ensuing scandal dirtied Odell Academy’s reputation enough that the board of trustees ordered the headmaster to fix the problem, once and for all. The previous dorm head was a French teacher from Montreal, a single guy, who smoked two packs of cigarettes a day—hardly the image the school was looking for. He got demoted, and Heath and Sarah—respected teachers, both Odell grads themselves—were brought in to replace him. A wholesome young couple with two adorable little kids to set a proper example. That was the plan, at least. But there was a problem. Neither Sarah nor Heath had a counseling background. They knew nothing about running a dorm, or providing guidance to messed-up girls. Sarah had spent her Odell years hiding from girls like that, and—to be honest—Heath had spent his chasing them. That was all in the past of course. The distant past. But it worried her.

When Sarah raised her concerns, Heath soothed them away and convinced her that this new job was their golden opportunity. How could they say no? Heath had big plans. He wanted to advance through the ranks and become headmaster one day. The dorm head position was his stepping-stone. He didn’t have to tell her how much he wanted it, or remind her how desperately he needed a win. She knew that, too well. Teaching high school English was not the life Heath wanted. There had been another life, but it crashed and burned, and they’d barely survived. With this new challenge, Heath was finally happy again. She couldn’t stand in his way.

And he was happy. He strode into the kitchen now looking like a million bucks, decked out in a blue blazer and a new tie, with a huge smile on his handsome face.

“Ready, babe?” he said, coming over and planting a kiss on Sarah’s lips.

“Just about. You look happy,” she said, lifting Scottie down from his high chair.

“You bet. I’ve got my speech memorized. I’ve got my new tie on for luck—the one you got me for my birthday. How do I look?”

“Gorgeous,” she said.

It was true. The first time Sarah had laid eyes on Heath was here at Odell, fifteen years ago, when he showed up as a new transfer student their junior year. He was the most beautiful thing she’d ever seen back then, and, despite the ups and downs, that hadn’t changed.

Heath checked his watch, frowning. “It’s after nine. You’d better get dressed.”

Sarah had thought she was dressed. She’d brushed her hair this morning, put on a skirt, a sweater and her favorite clogs, as she usually did on days when she had to teach class. But looking at Heath in his finery, she realized that her basic routine wouldn’t cut it in the new job. She’d have to try harder. That wasn’t comfortable, any more than it had felt natural earlier this week to give up their cozy condo in town and move into this faculty apartment. Moreland Hall was gorgeous, like something out of a fairy tale. Ivy-covered brick and stone, Gothic arches, ancient windows with panes of wavy glass. The apartment had a working fireplace, crown moldings, hardwood floors. But it didn’t feel like home. How could it? It didn’t belong to them; not even the furniture was theirs. Not to mention that the kitchen window looked directly onto the Quad. Anybody could look in and see her business. Life in a fishbowl. She hoped she could get used to it.

“Harper’s getting dressed,” Sarah said. “I’ll take care of Scottie. Can you move the refreshments to the common room and start setting up?”

“Sure thing. And, babe, don’t be afraid to do it up, okay? You look hot when you dress up.”

Heath grinned and winked at her, but Sarah couldn’t help completing the thought in her mind. Unlike the rest of the time, when you look like you just rolled out of bed. But Heath hadn’t said that, and didn’t think it. That was Sarah’s insecurity speaking.

It took fifteen minutes to clean up Scottie, coax him out of his pajamas and into some semblance of decent clothes. Five more minutes were spent swapping out Harper’s Elsa costume (which was what she’d meant by “party dress”) for an actual dress. That left Sarah ten minutes to dress herself. She dug through boxes, but couldn’t find her good fall clothes. She ended up throwing on a flowery sundress because it was the only pretty thing she could lay hands on, but topping it with a woolly cardigan against the September breeze. Not her most polished look, but it would have to do. She swiped on some bright lipstick, gathered the kids and the dog, and set out for the common room.

They were only a few minutes late, but when she got there, the room was empty, the tables and chairs were missing, and Heath was nowhere to be seen. She had a minor heart attack, until she caught the sound of Heath’s rich laugh floating in through the open window, and looked out onto the Quad. Her husband stood on the lush, green lawn, surrounded by the missing furniture, and a gaggle of leggy, giggling girls.

“Hey, what are you doing out there?” Sarah called, laughter in her voice as she stuck her head out the window. With Heath, you could always expect the unexpected.

He turned, flashing a movie-star grin.

“Here’s my lovely wife now. Girls, may I introduce your new dorm cohead, the amazing and brilliant Mrs. Sarah Donovan. Babe, come on out. It’s a beautiful day, I thought, why not party on the Quad?”

Party on the Quad? Girls whooped and high-fived at that. Did Heath understand who he was dealing with? Sarah had some of these girls in her math classes in years past. They were the worst offenders, the delinquents, the old-school Moreland girls, accustomed to bad behavior and few repercussions. She’d have to sit Heath down and have a talk about setting an example.

Sarah led her children and the dog down the hall and out the front door of Moreland Hall. They stepped into the sunshine of the perfect September day. Harper ran to her daddy, who hoisted her up onto his hip. Max, their German shepherd mix, ran circles on the lawn, as Scottie chased after him, squealing. Music filtered out from a dorm room farther down the Quad. And those Moreland girls—the same ones who surfed the Web in her classroom and snarked behind her back—made a fuss over her, and said how much they liked her dress. She didn’t buy the phony admiration. As they circled around her, long-legged and beautifully groomed, drawling away in their jaded voices, Sarah felt like they might eat her alive.

3

It was the first day at a new school for Bel Enright and her twin sister, Rose. Bel hated Odell Academy on sight. But she’d promised Rose to give it a real try, so she kept silent, and smiled, and pretended to be okay when she wasn’t.

It was early September. Their mother had died in May, and Bel was still reeling. The cancer took their mom so fast that Bel couldn’t believe she was gone. Mom had been Bel’s best friend, her inspiration. She’d worked in an insurance company to support her girls, but the rest of the time, she was an artist. She painted, and made jewelry from found objects. She wrote poetry and cooked wonderful food. They lived in a two-bedroom apartment in the Valley with thin walls and dusty palm trees out front. But inside, their place was beautiful, furnished with flea-market finds, hung with Mom’s landscapes of the desert, lit with scented candles. Mom was beautiful—the raven hair and green eyes that Bel had inherited (where Rose was blond like their father), the graceful way Mom moved, her serene smile. And now she was gone.

Bel had this fantasy that the twins would go on living in the apartment, surrounded by Mom’s things, by her memory. But they were only fifteen, and it was impossible. Rose was the practical one, and she made Bel understand this. In the week after Mom died, Bel lay in bed and cried while Rose made funeral arrangements and phone calls. Mom was a dreamer, like Bel, and hadn’t provided particularly well for the twins’ future. Who expected to die at forty, anyway? She’d left no will and no guardian, only a modest insurance policy, which Rose insisted they save to pay for college. Bel didn’t know if she wanted to go to college. But she understood that they needed a place to live, or they’d wind up in foster care. Rose called all of Mom’s friends and relatives. Her brother in San Jose, her cousins in Encino, her BFF from childhood, her girlfriends from work. Rose also called Grandma—Martha Brooks Enright, their father’s mother, whom they hadn’t seen since Dad died when they were five. Bel objected to that. Why invite Grandma to the funeral when she hadn’t bothered to see them all these years? She wouldn’t even come. But Rose said they had to try because there was no telling who’d be willing to take them in.

All the people Rose contacted came to the funeral, including Grandma. Mom dying so young, leaving the twins orphaned, tugged at people’s heartstrings. Everybody cried, and said pretty things, but it was empty talk. The only person who actually offered to take them in was their grandmother—who was Rose’s first choice, and Bel’s absolute last. Grandma gave Bel a cold feeling. She was so remote, in her tailored black dress and pearls. She was also the only person who didn’t cry at the funeral. Bel noticed that. She noticed that Grandma didn’t seem to like Mom much, based on how she talked about her. Grandma, being such a blue blood, maybe hadn’t been happy about her son marrying a girl from the wrong side of the tracks. Bel’s parents had met in college, at an event honoring the Enright family for endowing a major scholarship. Mom was one of the scholarship recipients. That’s how different their situations were. John Brooks Enright was there representing his rich family, and Eva Lopez was there to say a required thank-you. But opposites attract. They fell in love.

When Dad died, Mom moved the twins back to California, and they didn’t see Grandma again, or even talk to her on the phone. She sent checks on their birthday; that was it. After the funeral, when Grandma took them to a restaurant and offered to have the girls come live with her, Bel confronted her. Why hadn’t Grandma come to see them all those years? Wouldn’t you know, she claimed it was all Mom’s fault, that she’d tried to visit, but was told she wasn’t welcome. Bel didn’t believe it for a minute, and afterward, she told Rose so. But Rose thought maybe Grandma was telling the truth. And besides, what choice did they have? Grandma was the only one willing to take them in.

At the end of May, a week and a half after Mom died, the twins went east to live with their grandmother in her big house in Connecticut. Grandma let them keep one painting each to hang in their rooms, but everything else went to Goodwill. They got on the plane with just one suitcase. Grandma would buy them new clothes better suited to life in a cold climate. It turned out that Grandma was very, very rich; something their mother had never told them. Rose thought they’d won the lottery. But to Bel, it all felt wrong. The Mercedes, the big house with its echoing rooms and elaborate décor, the housekeeper who came every day but barely spoke. She tried to settle in, to get used to the strange new circumstances. Maybe eventually she would have succeeded. But then the rug got pulled out from under them all over again when Grandma announced that she was shipping the twins off to boarding school come September.

Boarding school was something rich people did, but to Bel, it just seemed cold. Not only would they go to some pretentious prep school, but they would live there, and come home only for holidays. The whole idea was the brainchild of Warren Adams, Grandma’s silver-haired, silver-tongued boyfriend. Warren was a lot like Grandma: good-looking, dressed fancy all the time, talked with an upper-crusty accent. Bel didn’t trust him. Warren claimed he was merely Grandma’s lawyer, but if that was true, why did he hang around her house so much? He said he’d been a close friend of Grandpa’s, but then why was he moving in on Grandpa’s wife? And he insisted that boarding school was the best place for the twins, but Bel suspected that Warren wanted them out of the way, so he could have Grandma and her money to himself. Rose didn’t care. She didn’t care if Warren wanted them gone, or even if Grandma did. Odell Academy was one of the top schools in the country, and Rose wanted to go there. She was ambitious like that, and Bel was too depressed to argue. They applied, they got in, and now the day of reckoning had arrived.

That morning, Grandma woke them early. They packed their fabulous new belongings into the Mercedes and drove the three hours from Connecticut to Odell Academy in New Hampshire, where they drove through imposing brick-andiron gates onto a lush, green campus. Beautiful as it was, Bel felt like she was going to prison.

“Isn’t it lovely?” her grandmother said with a sigh. “I remember bringing your father here.”

In the back seat, Bel fought tears. But she could see Rose sitting next to Grandma in the front, staring out the window, awestruck.

“It’s the most beautiful place I’ve ever seen,” Rose said reverently.

They drove past perfectly manicured lawns, following signs to registration at the Alumni Gym. The gym parking lot was full of luxury cars with plates from New York and Connecticut and Massachusetts. The gym itself was housed in a grand marble building that looked like a palace. It made Bel miss her humble high school gym back in California, with its scarred floor and grimy lockers. She missed her old friends, the beach, their little apartment. Most of all, she missed her mother. A tear escaped and ran down her cheek.

“I want to go home,” she blurted.

Grandma met her eyes in the rearview mirror, looking alarmed.

“Isabel, dear, we’ve been over this. Odell is one of the top schools in the country.”

“I know I can’t go back to California. Just let me come home with you, Grandma. I’ll go to the public school. You’ll save so much money. Please.”

“It’s not about the money, darling. Odell is a family tradition. Your father and grandfather went here.”

Why did Grandma think that would matter to her? She’d never met her grandfather, and barely remembered her father. It was Mom who raised them. Mom had gone to public school, and she was the most intelligent and wonderful person Bel had ever known.

Rose reached across the seat and squeezed Bel’s hand. “Belly, you’re just nervous,” Rose said, using her childhood nickname. “First-day jitters. It’ll be okay. I’m here. We’re in this together.”

Bel tried to take comfort in that. It was true, she had her twin. Even if they were different, and didn’t always see eye-to-eye, Rose was family. Bel nodded, and swiped a hand across her eyes.

“Okay.”

Bel took a deep breath, and the three of them got out of the car. Inside, the Alumni Gym wasn’t just a gym, but an entire athletic complex, complete with an Olympic-size swimming pool and indoor tennis courts. Registration tables had been set up on the basketball court, a cavernous space surrounded by bleachers and flooded with light from tall windows. Bright blue banners crowded the walls, trumpeting Odell’s many championships against other prep schools. The room vibrated with voices and laughter, as kids and their parents greeted and hugged. Rose and Bel were coming in as sophomores, which meant that most kids in their grade knew each other already, but Bel tried not to care. Look at them—all stuffy and preppy, in head-to-toe Vineyard Vines. Who needed them? There must be other, cooler kids here somewhere. Kids like her friends back home, who smoked weed and surfed and let their hair grow wild. She and Rose had moved in such different crowds. Rose was a good girl. She got perfect grades, and did Model UN and stocked shelves at the food pantry. Her friends were dweebs like her—Bel meant that in a kind way. She loved her sister. Still, she wouldn’t be surprised if Rose fit right in at this stuck-up school.

The twins picked up their registration packets, which included dorm assignments, class schedules, IDs, and a campus map. Bel and Rose had been assigned to the same dorm, Moreland Hall.

Grandma studied their placement forms, nodding approvingly. “They usually separate siblings, but I requested that they keep you together, because of your loss. I’m so glad they listened.”

They got back into the car and followed the map to Moreland Hall. As they drove up to the turnaround behind the dorm, a group of pretty girls, with long hair and long legs and wearing matching blue Odell T-shirts, waved signs that read: WELCOME HOME MORELAND GIRLS! Home. As if this place could ever be that for Bel. The dorm was vast and built of dark brick, with arches and turrets and mullioned windows. Like a haunted house. It gave Bel the creeps. But she’d promised to try, and she would.

The twins got out of the car. One of the T-shirted girls stepped forward. She was blond and perfect-looking, but when she flipped her hair, Bel caught the unmistakable tang of cigarette smoke, which piqued her interest. Smoking was against the rules here, supposedly. But maybe not everyone followed the stupid rules.

“Hey, I’m Darcy Madden,” the girl said. “We’re the senior welcome committee. So, welcome, I guess.”

“Hi, Darcy! I’m Rose Enright, and this is my twin sister, Bel,” Rose said, stepping forward and smiling eagerly.

Darcy rolled her eyes.

“Right, the orphan twins,” Darcy said. “I heard all about you. It’s a scam, right? You don’t even look like twins to me. Bel’s got black hair and Rose has, hmm, what would you call that? Dirty blond?”

“We’re definitely twins,” Rose said, coloring. “But we’re fraternal, not identical. I look like my dad’s family, Bel looks like our mom.”

“Twins, maybe, but orphans? Since when do orphans wear Lacoste?” Darcy said, looking at Rose’s pink polo with its tiny alligator, a glint of amusement in her eyes.

“I am so an orphan. The definition of that is your parents dying, and mine did,” Rose protested.

Darcy caught Bel’s eye, and they both laughed at Rose’s earnestness. Bel then immediately felt guilty for laughing at her sister. But come on, Rose was uptight. A little teasing would do her good.

“She’s just joking,” Bel said to Rose.

“Yeah, sorry, kidding,” Darcy said. “Come on, orphans, we’ll help unload your stuff.”

Darcy beckoned, and more welcome-committee girls ran over. The extra hands were useful given the mountain of suitcases and boxes stuffed into the trunk of Grandma’s car. The last couple of weeks had been one massive shopping spree, as Grandma got them properly outfitted—her word—for Odell. Rose loved the pastel polo shirts Grandma suggested, the wool sweaters and boat shoes and Bean boots, the formal dresses for dances and dinners. Bel thought they were frumpy and boring. She’d made a stink, and when that didn’t work, she’d begged and pleaded. In the end, Grandma relented and bought Bel some cute things—tops and leggings, jeans, a moto jacket, black suede boots, a couple of minidresses. Both girls also got new phones and laptops, bedding and desk lamps, shower caddies and under-bed storage bins. Grandma didn’t stint, and Bel liked the stuff so much that she got over her hesitation at blowing so much cash. If Grandma didn’t mind, why should she?

Rose and Bel grabbed suitcases. The welcome-committee girls took boxes and they all headed into the dorm, as one girl held the door open for the others. Manners were a thing here, apparently. Bel was surprised not only at how much help was offered, but how respectfully the girls treated her grandmother. Then again, her elegantly dressed, beautifully coiffed grandma fit right in at Odell, better than Bel did. The girls refused to let Grandma carry a thing, and a girl was deputized to take her in the elevator and show her the twins’ rooms so she wouldn’t have to hike up the steep, slippery marble steps.