Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «Doves of War: Four Women of Spain»

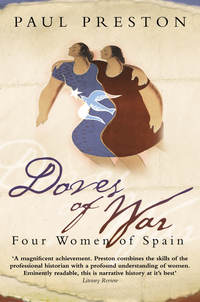

DOVES OF WAR

Four Women of Spain

PAUL PRESTON

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

PROLOGUE: Fears and Fantasies

PRISCILLA SCOTT-ELLIS: All for Love

NAN GREEN: A Great Deal of Loneliness

MERCEDES SANZ-BACHILLER: So Easy to Judge

MARGARITA NELKEN: A Full Measure of Pain

EPILOGUE

NOTES

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

PRAISE

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

PROLOGUE Fears and Fantasies

IN LATE SEPTEMBER 1937, two English women arrived in Paris. One, a penniless housewife and Communist Party militant from London, had travelled on the crowded boat train from Calais. Despite being exhausted after her trip, she left her luggage at the station and got a bus straight to the recently inaugurated Great Exhibition. The other, the daughter of one of the richest aristocrats in England, accompanied by a princess, the granddaughter of Queen Victoria, arrived in a gleaming limousine. After checking in at their luxurious hotel in the Rue de la Paix, she dined out. The next day, after a little shopping, she too visited the exhibition. So great was the bewildering cornucopia spilling out of the two hundred and forty pavilions jostling along the banks of the Seine that only a small part of their wonders could be seen in a few hours. The two women had to make choices. What they decided revealed much about where they had come from and about where they were going.

The Communist made a beeline for the pavilion of the Spanish Republican Government and ‘stood spellbound at Picasso’s Guernica’. She was repelled by ‘the competitive vulgarity’ of the German and Soviet pavilions which glared aggressively at each other at the end of the Pont d’Iéna on the Rive Droite of the Seine. In contrast, the society girl was captivated by the great German cubic construction, designed by Albert Speer, over which flew a huge eagle bearing a swastika in its claws. Although, like her poorer compatriot, she was en route to the Civil War raging to the south, she did not bother to visit the pavilion of the Spanish Republic. They did both share utter contempt for the British display. The Communist ‘snorted in disdain at the British contribution – mostly tweeds, pipes, walking sticks and sports gear’. The aristocrat considered the British pavilion’s displays of golf balls, marmalade and bowler hats to be ‘very bad’.

The two English women never knew that they had coincided at the Paris exhibition any more than that their paths had crossed before. Three and a half months earlier, the aristocrat had emerged from a cinema in Leicester Square and watched a Communist demonstration protesting about the German navy’s artillery bombardment of Almería in South Eastern Spain. Amongst those chanting ‘Stop Hitler’s War on Children!’ was the left-wing housewife. For both women, Paris was just one stop on a longer journey to Spain. Their preparations in August 1937 could hardly have been more different. The Communist had thought long and hard about leaving England and her son and daughter to volunteer for the Spanish Republic. With trepidation, she sold what she could of her books and household chattels and deposited the rest in a theatrical skip. At Liverpool Street Station in London, she bade a painful farewell to her two children and then put them on a train to a boarding school paid for by a wealthy Party comrade. A month before her thirty-third birthday, the petite brunette leftist had little by way of possessions. She had hardly any packing to do for herself, just a few clothes – her two battered suitcases were crammed with medical supplies for the Spanish Republican hospital unit that she hoped to join. Clutching her burdens, she took a bus to Waterloo Station to catch the train to Dover.

Her counterpart’s preparations were altogether more elaborate. For more than six months, she had dreamed of nothing else. She was in love and hoped that by going to Spain she would win the attention of her beloved, a Spanish prince serving with the German Condor Legion. During the summer of 1937, in the intervals between riding, playing tennis and learning golf, she took Spanish lessons with a private tutor. In London’s West End, her punishing schedule of shopping was interspersed with inoculations, and visits to persons likely to be useful for her time in Spain. These included one of the four men with principal responsibility for British policy on Spanish affairs at the Foreign Office and the ex-Queen Victoria Eugenia of Spain. Not yet twenty-one, the blonde socialite, rather gawky and deeply self-conscious about her weight, desperately haunted the beauty salons in preparation for her Spanish adventure. She left England in the chauffeur-driven limousine belonging to Victoria Eugenia’s cousin, Princess Beatrice of Saxe-Coburg. The car was overloaded with trunks and hatboxes containing the trophies of the previous four weeks’ shopping safaris. After being ushered by the station master at Dover into a private compartment on the boat train, they crossed the channel then motored on to Paris – to their hotel, more shopping and the visit to the Great Exhibition. On the following morning, she set off on the remainder of her journey south to the Spanish border, enjoying an extremely pleasant tour through the peaceful French countryside.

After seeing the Picasso, her left-wing compatriot hastened to collect her heavy cases and catch the night train to Spain. Crushed into a third-class carriage, she was able to reflect on the horrors that awaited her on the other side of the Pyrenees. She was an avid reader of the left-wing press and had received painfully eloquent letters from her husband. He was already in Spain, serving as an ambulance driver with the International Brigades. By contrast, the young occupant of the limousine bowling along the long, straight, tree-lined French roads was blithely insouciant. Her knowledge of the Spanish Civil War was based on her reading of a couple of right-wing accounts which portrayed the conflict in terms of ‘Red atrocities’ and the knightly exploits of Franco’s officers. She sped towards Biarritz like a tourist, in a spirit of anticipation of wonders and curiosities to come. Her mind was on the object of her romantic aspirations, and she was thinking hardly at all of the terrors that might lie before her.

Both women were sustained by their fantasy of what their participation in the Spanish war might mean. For the aristocrat, it was about love and a chivalric notion of helping to crush the dragon of Communism. The Communist’s hopes were more prosaic. She wanted to help the Spanish people stop the rise of fascism and, deep down, vaguely hoped that doing so might be the first step to world revolution. Neither the aristocrat setting out to join the forces of General Franco nor the Communist could have anticipated the suffering that awaited them. Even the gruesome picture of the bloodshed at the front provided by the graphic letters from her husband had not fully prepared the left-winger en route to serve the Spanish Republic for the reality of war. By that late summer of 1937, however, the women of Spain had already been coming to terms with the horrors of war for over a year. For most of them, there had been no question of volunteering to serve. They had little choice – the war enveloped them and their families in a bloody struggle for survival. For two Spanish mothers, in particular, the war would have the most wildly unexpected consequences in terms of both their personal lives and the way in which they were dragged into the public sphere. Both were of widely differing social origins and political inclinations and had different hopes for what victory for their side might mean for them and their families. Their lives – and their fantasies – would be irrevocably changed by the war.

In the first days of the military uprising of 18 July 1936, one, a young mother of three, who had just turned twenty-five, had every reason to expect dramatic disruption in her life as a consequence of the war. She lived in Valladolid in Old Castile, at the heart of the insurgent Nationalist zone, and her husband was a prominent leader of the ultra-rightist Falange. Already, as a result of his political beliefs, she had experienced exile and political persecution. She knew what it was like to be on the run and to keep a family with a husband in jail. Because of his political activities, she had endured one childbirth completely alone and, in exile, had undergone a forceps delivery without anaesthetic. Nevertheless, she had stifled whatever resentment she might have felt as a result of her husband’s political adventures and supported him unreservedly. Now four months pregnant, the outbreak of war brought all kinds of possibilities and dangers. She rejoiced at his release from prison as a result of the military uprising and shared his conviction that everything for which they had both made so many sacrifices might come to fruition within a matter of weeks, if not days. Not without anxiety about the final outcome, she could now hope that her husband’s days as a political outlaw were over, that they could build a home together and that they and their children would be able to live in the kind of Nationalist Spain to which he had devoted his political career.

Within less than a week of their passionate reunion, both her husband and her unborn child would be dead. The reality of the war had smashed its way into her world and shattered her every hope and expectation. In an atmosphere charged with hatred, calls for revenge for her husband’s death intensified the savage repression being carried out in Valladolid. Confined to bed, she found little consolation in the bloodthirsty assurances of his comrades. She faced a bleak future as a widow with three children. Her own parents were long since dead and the best that her in-laws could suggest was that she earn a comfortable living by getting a licence to run an outlet for the state tobacco monopoly (un estanco). To their astonishment, after a relatively short period of mourning, she renounced both thoughts of vengeance and of a quiet life in widow’s weeds. She dug deep into her remarkable reserves of energy and embarked on a massive task of relief work among the many children and women whose lives had been shattered by the loss of fathers and husbands through death at the front, political execution or imprisonment. By the time that the two English women were packing their cases for Spain, she had fifty thousand women at her orders and was being feted in Nazi Germany by, among others, Hermann Göring and Dr Robert Ley, the head of the German Workers’ Front. By the end of the war, she would be – albeit briefly – one of the most powerful women in Franco’s Spain. Such triumphs, at best poor consolation for her personal losses, would see her embroiled in an unwanted rivalry with the leader of the Francoist women’s organisation, Pilar Primo de Rivera, and in the ruthless power struggles that bedevilled both sides in the Civil War.

In Republican Madrid, another mother, a distinguished Jewish writer and art critic, and a Socialist member of parliament for a southern agrarian province, was beset by a tumultuous kaleidoscope of feelings as a result of the outbreak of war. On the one hand, she hoped that the military uprising would be defeated and that a revolution would alleviate the crippling poverty of the rural labourers that she represented. On the other, she felt both pride and paralysing anxiety as a result of the wartime activities of her children. As soon as the military rebellion had been launched, militiamen had raced to the sierras to the North of Madrid to repel the insurgent forces of General Mola. Among them was the woman’s fifteen-year-old son. Despite her desperate pleas, he lied about his age and enlisted in the Republican Army. After three months training, he received a commission as the Republic’s youngest lieutenant. She tried to use her influence to keep him out of danger, but he successfully insisted on a posting in the firing line and took part in the most ferocious battles of the war. Her twenty-two-year-old daughter was a nurse at the front. Conquering her worries, their mother threw herself into war work, collecting clothes and food for the front, giving morale-raising speeches, organising the evacuation of children, and welfare work behind the lines. Like her Nationalist counterpart, she too would travel to raise support for her side in the war. And she too would find herself in an inadvertent rivalry – in her case, with the most charismatic woman of the Republican zone, Dolores Ibárruri – Pasionaria. Unlike the mother from Valladolid, for her there would be no victory, even a tainted one. The defeat of the Republic meant, for her, as for the many thousands who trudged across the Pyrenees into exile, incalculable personal loss and the crushing of the hopes which had underpinned her political labours. With the end of the war, her troubles were just beginning.

These four women, despite their different nationalities, social origins and ideologies, had much in common. They were brave, determined, intelligent, independent and compassionate. To differing degrees, all were damaged by the Spanish Civil War and its immediate and long-term consequences. As a direct result of the war, two would be widowed, two would lose children. Two would be deeply traumatised by their experiences in the front line. The shadow of the Spanish Civil War would hang over the rest of all their lives.

This book has no theoretical pretensions. Its objective is quite simple – to tell the unknown stories of four remarkable women whose lives were starkly altered by their experiences in the Spanish Civil War. All of them are relatively unknown. Neither of the two English women who served in the medical services of each zone had any political prominence at all. The two Spanish women who did have a notable public presence, the one in the Republican zone, the other in Nationalist Spain, were involved in tasks at some remove from the decision-making of the great war leaders of the two sides in conflict. Moreover, both at the time and subsequently, they functioned in the shadow of more famous rivals. None the less, for the purposes of this book, that is an advantage. Political detail takes a back seat, or is at least considered in the context of other personal relationships – with lovers, husbands and children. In that sense, this is a work of emotional history. It follows them from birth to death, in an attempt to show how, as women, wives and mothers, their lives were altered forever by the political conflicts of the 1930s, how their lives were altered for ever by the political conflicts of the 1930s, by the Spanish Civil War and by its consequences. It is hoped thereby to cast light into some unfamiliar corners of the conflict.

Writing the book has been a singularly emotional experience as well as a major effort of detective work. It is not the first time that I have written biography but my previous efforts have focused on more politically important figures. National prominence provided a chronological framework lacking from the material left behind by the four women whose lives are reconstructed here. The diaries and letters written by women tend to be much more intimate than those left by men. Accordingly, in the lives of all four of the women portrayed in this book, the personal has considerable priority over the public. Deeply aware of the problems of being a man writing about women, in the course of writing them, I asked many friends to read drafts of the different chapters. One of these readers is well-versed in both feminist and postmodernist theory. I was much heartened when she remarked encouragingly about one of my chapters that ‘even the theoretically illiterate can occasionally arrive at important insights by the use of antiquated empirical methods’. The implication is that it could all have been worked out by theory without all the messy biographical details. Even had I known how to do so, I fear that I would have thereby missed out on a moving experience and the reader would have missed the opportunity to know about four remarkable lives.

PRISCILLA SCOTT-ELLIS All for Love

THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR has given rise to a gigantic bibliography running into more than fifteen thousand books. In 1995, a remarkably original addition to the literary legacy of the conflict passed almost unnoticed. Its importance was obscured by the fact that it appeared on the list of a small English publishing house in Norfolk. The Chances of Death consisted of an edited selection from a voluminous diary written between the autumn of 1937 and the end of the war by Priscilla Scott-Ellis.1 The author, who had died twelve years earlier, was one of only two British women volunteers who served with Franco’s Nationalist forces during the war. Her vibrantly written and transparently honest account of her experiences is a mine of original insights into life behind the lines of the Francoist zone. Gut-wrenching descriptions of the front-line medical services alternate with accounts of the luxury still enjoyed in the rearguard by the Spanish aristocracy. Although highly readable, and deserving of a wider audience, there was every chance that this remarkable book would be a reference only for scholars.

However, an appreciative article published in the Madrid daily El País by the British historian Hugh Thomas provoked an astonishing polemic which in turn guaranteed that the book would be translated and published in Spain. Once at the centre of the ensuing scandal, the book, taken up by one of the country’s most prestigious publishers, achieved considerable popular success. Hugh Thomas’s glowing review, entitled ‘Sangre y agallas’ (blood and guts), gave an entirely accurate picture of the book’s merits. He praised its vivid portrayal of life in an emergency medical unit and its equally fascinating account of high society behind the lines. He also commented rightly that the diary presented an image of a brave, self-sacrificing but fun-loving girl, tirelessly driven by curiosity and enthusiasm.2 Nine days later, a disputatious reply was published in the pages of El País’s Barcelona rival, La Vanguardia. Entitled ‘Un enigma’, its author was José Luis de Vilallonga y Cabeza de Vaca, the Marqués de Castellvell, a playboy and journalist, known for his appearance in several Spanish and French films, for several successful novels published in France and for a semi-official biography of the King of Spain, Juan Carlos, with whom he claimed friendship.3

Vilallonga attacked the editor of Priscilla Scott-Ellis’s diary, Raymond Carr, claiming that it was a forgery ‘written by God knows who and with what sinister intentions’. Accordingly, he dismissed Hugh Thomas’s remarks as the fruit of ignorance. Vilallonga justified these assertions by the fact that he had been married to Priscilla Scott-Ellis for seventeen years, from 1945 to 1961. He found it incredible that she had never mentioned such a diary to him. He now demanded to know the identities of ‘the real author of this diary’ and of the beneficiary of the book’s profits. Along the way, he presented a cruelly dismissive account of Priscilla Scott-Ellis and her family. He asserted that the author was incapable of writing a diary, claiming that her prose was ‘infantile’. He described her father, the Lord Howard de Walden, as a whisky-sodden alcoholic. He alleged that Priscilla Scott-Ellis was in fact illegitimate and really the fruit of an adulterous affair between her mother and Prince Alfonso de Orléans Borbón, a cousin of Alfonso XIII and a close friend of her parents. He further insinuated that the great love of her life, Ataúlfo de Orléans Borbón, who was in some ways inadvertently responsible for her decision to go to Spain, was a homosexual. His own marriage to her was thus presented as a way out of an embarrassing situation for Prince Alfonso. He stated that his own parents never approved of the marriage ‘to a foreigner through whose veins there coursed Jewish blood’.

Some weeks later, Vilallonga’s diatribe brought forth a dignified reply from Sir Raymond Carr.4 He pointed out that Vilallonga’s questions about the authorship and the royalties constituted an accusation that, for money, he had knowingly undertaken to prepare an edition of a forgery. Carr gave an account of the genesis of the diary and an explanation of the circumstances whereby it had lain unpublished for half a century. In fact, it had been on the point of publication in the autumn of 1939 but the project was aborted because of the outbreak of the Second World War. Carr also published in facsimile a section of the diary. He then went on to underline some of the inaccuracies of Vilallonga’s account of Priscilla Scott-Ellis’s experiences during the Spanish Civil War. Finally, in a spirit more of sadness than of anger, he expressed his surprise that ‘a Spanish gentleman should assert in a newspaper that his wife, deceased and unable to defend herself, was a bastard and her father a drunk’. He found it tragic that Vilallonga’s article should thus ‘defame the memory of a valiant and indomitable woman’.

Who then was this remarkable woman? Esyllt Priscilla Scott-Ellis – known as ‘Pip’ – was the daughter of two remarkably creative and eccentric parents, Margherita (Margot) van Raalte and Thomas Evelyn Scott-Ellis, the eighth Lord Howard de Walden and fourth Lord Seaford. Margot was born in 1890, the daughter of an extremely wealthy banker of Dutch origins, Charles van Raalte, and Florence Clow, an English women with some talent as an amateur painter. Florence van Raalte was such a snob that she was known in the family as Mrs van Royalty. From her parents, Margot had inherited money and both musical and artistic talent. She was a good painter and an accomplished musician. Her singing voice was good enough for her to be trained for the opera with Olga Lynn and she often gave concerts, even being conducted – in Debussy’s La Demoiselle Élue – by Sir Thomas Beecham. These interests would provide a formative influence in Pip’s childhood. Margot’s family lived at Aldenham Abbey near Watford in Hertfordshire, where they were often joined by members of the Spanish royal family. The Infanta Eulalia, Alfonso XIII’s aunt and a woman of scandalous reputation, was a friend of Margot’s parents. Princess Eulalia’s two sons, Prince Alfonso and Prince Luis de Orléans Borbón, were being educated at English boarding schools and often spent summer holidays with the family. In the late 1890s, the Van Raalte family bought the paradisical Brownsea Island in Poole harbour. With its medieval castle, two fresh-water lakes and dykes and streams, it was a wonderful place for children. Margot spent many idyllic summers there with other children including Prince Ali and Prince Luis. It was on Brownsea Island that Lieutenant-General Baden-Powell, a friend of Margot’s father, launched his Boy Scout Movement in 1907.5

Tommy Scott-Ellis was born in 1880. A soldier and a great sportsman, he was educated at Eton and Sandhurst. He was commissioned into the 10th Hussars in 1899 and fought in the Boer War. The man presented by Vilallonga as a helpless sot was actually a good cricketer and boxer and was the English amateur fencing champion. In 1901, he became an immensely rich man at the age of twenty-one when he inherited his father’s title and the fortune of his grandmother, Lady Lucy Cavendish-Bentinck. He then bought a racing motorboat and competed in highly perilous cross-Channel races. He also bought a yacht and was a member of the British Olympic Team in 1906. He then acquired racing stables. In his childhood, he too had spent happy summers at Brownsea Island which was then owned by the Cavendish-Bentinck family. Having had a bitterly miserable time at various boarding schools, Brownsea became a haven for him. He now tried unsuccessfully to buy it. Deeply disappointed, he was consoled when the new owners, Charles and Florence van Raalte, turned out to be friends of his mother, Blanche. He was thus invited to Brownsea to sail in summer and to shoot in winter.6

Shortly after marrying Margot van Raalte, Tommy, anxious to keep a link with the Army, joined the Westminster Dragoons. Their first children, twin sister and brother, Bronwen and John Osmael, were born on 27 November 1912. When the First World War broke out, Tommy left for Egypt as second-in-command of his regiment. At the time Margot was pregnant with their third child, Elizabeth, who was born on 5 December 1914. At the first opportunity, however, she arranged to join Tommy in Egypt. As was commonplace among the upper classes at the time, Margot thought it normal to leave her three children with a nurse. At Chirk Castle, the family’s country seat near Llangollen in North Wales, they were neglected to the extent of contracting rickets.7 At first Margot was rather bored in Egypt but after Tommy volunteered to go with the British invasion forces to Gallipoli, and casualties began to arrive from Turkey, she joined a friend, Mary Herbert, the wife of Aubrey Herbert, a contemporary of Tommy’s at Eton, in setting up a hospital. One of the Herberts’ daughters, Gabriel, was also to work with Franco’s medical services during the Spanish Civil War; the other, Laura, was to be the second wife of the novelist Evelyn Waugh. At the end of 1915, Tommy was posted back to Egypt and Margot was able to live with him there until in May 1916, they returned to England. She was by then pregnant once more. In November 1916, Tommy got himself transferred to the Royal Welsh Fusiliers in order to serve in France. Two days after he left, Priscilla was born in London on 15 November 1916. The real sequence of events undermines Vilallonga’s accusation that her father was Prince Alfonso de Orléans Borbón.8 Margot and Tommy would have two further daughters, Gaenor, born on 2 June 1919 and Rosemary on 28 October 1922.

In later life, when she had become addicted to drama and excitement, Pip would attribute her taste for adventure to having been born during an air raid; more likely it was inherited from her parents. According to her brother, when she was a toddler, the family called her ‘Chatterbox’. Ensconced in her high chair, she would chunter away irrespective of anyone listening or understanding. As a child, she used her Welsh name of Esyllt (the equivalent of Iseult or Isolde). However, she quickly became irritated when people twisted this to Ethel, so she switched to Priscilla, which in turn became reduced to Pip. Her mother remembered how useful she always made herself with her younger sisters: Rosemary was a rascal, ‘Pip alone could manage her with loving ease.’ Pip was an affectionate child, always desperate to please and to be liked – and thus hurt by the coldness of her parents. Gaenor recalled that Pip was ‘a very pretty girl with golden curls and blue eyes, and bitterly resented the disappearance of the curls and her entry into the comparative drabness of schoolroom life’. She was brought up in the splendour of Seaford House in Belgrave Square until she was nine, attending a London day school – Queen’s College in Harley Street. While still a child in London, she suffered a distressing riding accident in Rotten Row in Hyde Park. She was thrown from her horse and when her foot was caught in a stirrup she was dragged some distance. She was nervous about riding for a while but, according to her sister, ‘she grew up to become an extremely brave horsewoman, and to show courage in all sorts of difficult and dangerous situations’.9

Withal, it was a privileged existence. Margot was concerned that her children be independent and resourceful which was difficult given the legions of servants whose job it was to make life easy for the family. With a great imaginative leap, considering her own station in life, Margot supposed that ‘some, if not all, of the girls might have to cope and ‘‘manage’’ in later life’. To create a contrast with the world of housemaids who cleared up books and toys and grooms who saddled and rubbed down horses and ponies, a little house was built at Chirk called the Lake Hut. There, the girls made do on their own, cooking, washing-up, and looking after themselves. Pip took to this very well. When their parents took the children on trips on their sixty-foot motor launch, Etheldreda, Pip and Gaenor would do the cooking. In her mother’s recollection, ‘when it was rough it was Pip who managed to produce food for us all. She was gallant and highly efficient at ten and twelve years old.’ Holidays at Brownsea were enlivened by days camping at nearby Furzy Island. Indeed, Chirk, Brownsea and Furzy provided the basis of blissful fun for the children. They had considerable independence to wander the fields, the woods and streams. When they were required for meals, if Margot was present, she would unleash the power of her soprano in Brünnhilde’s call from Die Walküre and they would come scampering home.10

All in all, there were idyllic elements but there remains a question mark about the impact on the children of the lengthy separations from both Margot and Tommy. The Scott-Ellis girls saw relatively little of their parents, particularly of their father. When they did, emotional warmth was in short supply. Tommy and Margot were, according to their son, incapable of showing emotion. They both seemed totally remote, capable of impersonal kindness but not of understanding. Pip’s cousin Charmian van Raalte, who was brought up with the Scott-Ellis girls, having been abandoned by her own mother, recalled that ‘neither Tommy nor Margot ever showed a grain of affection to any of the children’. Indeed, when Thomas Howard de Walden returned from France, where he had fought in the mass slaughter of Passchendaele, he was dourly taciturn, in shock from the shelling and the butchery. In his own description, part of him had died in the war and the part that survived was ‘no more than a husk, living out a life that he finds infinitely wearisome’.11 However, on the rare occasions when their parents did acknowledge the existence of the children, they seemed, fleetingly, to have fun together. Lord Howard de Walden had a burning interest in the theatre as well as being a musician of some talent. At Chirk, he would often delight guests with his playing in the music room. He wrote the libretto for three operas by Joseph Holbrooke. He ran the Haymarket Theatre for several years. He often organised theatrical events involving his children and their friends, writing six plays for them. With professionally produced costumes and scenery, these were exciting enterprises. In one, a part was taken by Brian Johnston, later famous as a broadcaster. Moreover, baskets of costumes from old productions at the Haymarket, with armour and helmets, ended up in the family home, swelled the dressing-up basket and transformed many childhood games.