Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «Juan Carlos: Steering Spain from Dictatorship to Democracy»

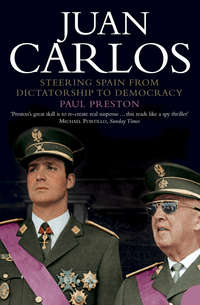

JUAN CARLOS

A People’s King

PAUL PRESTON

In Memory of José María Coll Comín

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

CHAPTER ONE: In Search of a Lost Crown 1931–1948

CHAPTER TWO: A Pawn Sacrificed 1949–1955

CHAPTER THREE: The Tribulations of a Young Soldier 1955–1960

CHAPTER FOUR: A Life Under Surveillance 1960–1966

CHAPTER FIVE: The Winning Post in Sight 1967–1969

CHAPTER SIX: Under Suspicion 1969–1974

CHAPTER SEVEN: Taking Over 1974–1976

CHAPTER EIGHT: The Gamble 1976–1977

CHAPTER NINE: More Responsibility, Less Power: the Crown and Golpismo 1977–1980

CHAPTER TEN: Fighting for Democracy 1980–1981

CHAPTER ELEVEN: Living in the Long Shadow of Success 1981–2002

BIBLIOGRAPHY

NOTES

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

About the Author

Praise

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

CHAPTER ONE In Search of a Lost Crown 1931–1948

There are two central mysteries in the life of Juan Carlos, one personal, the other political. The key to both lies in his own definition of his role: ‘For a politician, because he likes power, the job of King seems to be a vocation. For the son of a King, like me, it’s something altogether different. It’s not a question of whether I like it or not. I was born to it. Ever since I was a child, my teachers have taught me to do things that I didn’t like. In the house of the Borbóns, being King is a profession.’1 In those words lies the explanation for what is essentially a life of considerable sacrifice. How else is it possible to explain the apparent equanimity with which Juan Carlos accepted the fact that his father, Don Juan, to all intents and purposes sold him into slavery? In 1948, in order to keep the possibility of a Borbón restoration in Spain on Franco’s agenda, Don Juan permitted his son to be taken to Spain to be educated at the will of the Caudillo. In a normal family, this act would be considered to be one of cruelty, or at best, of callous irresponsibility. But the Borbón family was not ‘normal’ and the decision to send Juan Carlos away responded to a ‘higher’ dynastic logic. Nevertheless, the tension between the needs of the human being and the needs of the dynasty lies at the heart of the story of the distance between the fun-loving boy, Juanito de Borbón, and the rather stiff prince Juan Carlos with his perpetually sad look. The other, rather more difficult puzzle, is how a prince emanating from a family with considerable authoritarian traditions, obliged to function within ‘rules’ invented by General Franco, and brought up to be the keystone of a complex plan for the continuity of the dictatorship should have committed himself to democracy.

The mission to which Juan Carlos was born, and which would take precedence over any personal life, was to make good the disaster that had struck his family in 1931. On 12 April 1931, nationwide municipal elections had seen sweeping victories for the anti-monarchical coalition of Republicans and Socialists. King Alfonso XIII, an affable and irresponsible rake, had earned considerable unpopularity for his part in the great military disaster at Annual in Spain’s Moroccan colony in 1921. Even more, his collusion in the establishment of a military dictatorship in 1923 had sealed his fate. When he learned that his generals were not inclined to risk civil war in order to overturn the election results, he gave a note to his Prime Minister, Admiral Aznar. ‘The elections celebrated on Sunday show me clearly that today I do not have the love of my people. My conscience tells me that this wrong turn will not last forever, because I always tried to serve Spain, my every concern being the public interest even in the most difficult moments.’ He went on to say, ‘I do not renounce any of my rights.’ In that statement can be distantly discerned the process whereby Spain lost a monarchy, suffered a dictatorship and regained a monarchy. The hidden message to his supporters was that they should create a situation in which the Spanish people would beg him to return. This would be the seed from which the military uprising of 1936 would grow. However, its leader, General Franco, despite being a self-proclaimed monarchist and one-time favourite of Alfonso XIII, would not call him back to be King. One reason perhaps was that Alfonso XIII also said, ‘I am King of all Spaniards, and also a Spaniard.’ Those words would often be used by Alfonso’s son and heir, Don Juan, and would occasion the sarcastic mirth of the dictator. They would be used again on the day of the coronation of King Juan Carlos.2

On 14 April 1931, on his painful journey from Madrid, via Cartagena, into exile in France, the King was accompanied by his cousin, Alfonso de Orleáns Borbón. The Queen, Victoria Eugenia of Battenburg, a granddaughter of Queen Victoria, was escorted into exile by her cousin, Princess Beatrice of Saxe-Coburg, the wife of Alfonso de Orleáns Borbón.3 The government of the Republic quickly published a decree depriving the exiled King of his Spanish citizenship and the royal family of its possessions in Spain. After a short sojourn in the Hôtel Meurice on the rue de Rivoli in Paris, the royal family moved to a house in Fontainebleau. There, Alfonso XIII received delegations of conspirators against the Second Republic and gave them his approval and encouragement.4

In addition to the blow of exile, Alfonso XIII suffered considerable personal sadness. Without the scenery of the palace and the supporting cast of courtiers, the emptiness of his relationship with Victoria Eugenia was increasingly exposed. Not long after their arrival at Fontainebleau, the King remonstrated with the Queen about her closeness to the Duke and Duchess de Lécera who had accompanied her into exile. The marriage of the Duke, Jaime de Silva Mitjans, and the lesbian Duchess, Rosario Agrelo de Silva, was a sham but they stayed together because both were in love with the Queen. Despite persistent rumours, which niggled at Alfonso XIII, the Queen always vehemently denied that she and the Duke had been lovers. Nevertheless, when the bored Alfonso XIII took a new lover in Paris and the Queen in turn remonstrated with him, he tried to divert the onslaught by throwing in her face the alleged relationship with Lécera. She denied it but, as tempers rose, he demanded that she choose between himself and Lécera. Fearful of losing their support, on which she had come to rely, she replied, by her own account, with the fateful words, ‘I choose them and never want to see your ugly face again.’5 There would be no going back.

Another reason for Alfonso’s long-deteriorating relationship with Victoria Eugenia was the fact that she had brought haemophilia into the family. The couple’s eldest son, Alfonso, was of dangerously delicate health. He was haemophilic and, according to his sister, the Infanta Doña Cristina, ‘the slightest knock caused him terrible pain and would paralyse part of his body.’ He often could not walk unaided and lived in constant fear of a fatal blow. When the recently appointed Director General of Security, Emilio Mola, made his courtesy visit to the palace in February 1930, he was shocked: ‘I also visited the Príncipe de Asturias [the Spanish equivalent of the Prince of Wales] and only then did I fully understand the intimate tragedy of the royal family and comprehend the pain in the Queen’s face. He received me standing up and had the kindness to ask me to sit. Then he tried to get up to see me out and it was impossible: a flash, of anguish and of resignation, passed across his face.’6 Alfonso formally renounced his right to the throne on n June 1933 in return for his father’s permission to contract a morganatic marriage with an attractive but frivolous girl he had met at the Lausanne clinic where he was receiving treatment. Edelmira Sampedro y Robato was the 26-year-old daughter of a rich Cuban landowner.

Immediately following his eldest son’s renunciation of his dynastic rights, Alfonso XIII arranged for a number of prominent monarchists to put pressure on his second son, Don Jaime, to follow his brother’s example. Don Jaime was deaf and dumb – the result of a botched operation when he was four. Cut off from the world, both by dint of his royal status and his deafness, he had grown into a singularly immature young man. The monarchist leader José Calvo Sotelo persuaded him that his inability to use the telephone would significantly diminish his capacity to take part in anti-Republican conspiracies.7 Alfonso married Edelmira in Lausanne, in the presence of his mother and two sisters. Neither his father nor three brothers deigned to attend. On the same day, in Fontainebleau, 21 June 1933, Don Jaime, who was single at the time, finally agreed to renounce his rights to the throne, as well as those of his future heirs. The renunciation was irrevocable and would be ratified on 23 July 1945. In spite of this, he would later contest its validity, thereby complicating Juan Carlos’s rise to power.8

In his 1933 letter to his father, Don Jaime wrote: ‘Sire. The decision of my brother to renounce, for himself and his descendants, his rights to the succession of the crown has led me to weigh the obligations that thus fall on me … I have decided on a formal and explicit renunciation, for me and for any descendants that I might have, of my rights to the throne of our fatherland.’9 Don Jaime would, in any case, have lost his rights when, in 1935, he also made a morganatic marriage, to an Italian, Emmanuela Dampierre Ruspoli, who although a minor aristocrat was not of royal blood. It was not a love match and would end unhappily.10

In the summer of 1933, during a royal skiing holiday in Istria, Alfonso’s fourth son, Don Gonzalo – who also suffered from haemophilia – was involved in a car crash and died as a result of an internal haemorrhage.11 His first son fared little better. After his allowance was slashed by the exiled King, Alfonso’s marriage to Edelmira did not survive. They divorced in May 1937. Two months later, he married another Cuban, Marta Rocafort y Altuzarra, a beautiful model. The marriage lasted barely six months and they were also divorced, in January 1938. Having fallen in love with Mildred Gaydon, a cigarette girl in a Miami nightclub, Alfonso was on the point of marrying for a third time when tragedy once more struck the Borbón family. On the night of 6 September 1938, after leaving the club where Mildred worked, he too was involved in a car crash and, like his brother Gonzalo, died of internal bleeding.12

As a result of the successive renunciations of Alfonso and Jaime, the title of Príncipe de Asturias fell upon Alfonso XIII’s third son, the 20-year-old Don Juan. When he received his father’s telegram informing him of this, Don Juan was a serving officer in the Royal Navy on HMS Enterprise, anchored in Bombay. Because he realized that his new role would eventually involve him leaving his beloved naval career, he accepted only after some delay. In May 1934, he was promoted to sub-lieutenant and in September, he joined the battleship HMS Iron Duke. In March 1935, he passed the examinations in naval gunnery and navigation which opened the way to his becoming a lieutenant and being eligible to command a vessel. However, that would mean renouncing his Spanish nationality, something he was not prepared to do. His uncle, King George V, granted him the rank of honorary Lieutenant RN.13

Don Juan did not emulate his elder brothers’ disastrous marriages. On 13 January 1935, at a party given by the King and Queen of Italy on the eve of the marriage of the Infanta Doña Beatriz to Prince Alessandro Torlonia, Prince di Civitella Cesi, Don Juan had met the 24-year-old María de las Mercedes Borbón Orléans. Having faced the problem of his eldest son’s unsuitable marriage, Alfonso XIII was delighted when Don Juan began to fall in love with a statuesque princess who was descended from the royal families of Spain, France, Italy and Austria. They were married on 12 October 1935 in Rome. Several thousand Spanish monarchists made the trip to the Italian capital and turned the ceremony into a demonstration against the Spanish Republic. By this time, Queen Victoria Eugenia had long since left Alfonso XIII and she refused to attend the wedding.14 The newly appointed Príncipe de Asturias and his new bride settled at the Villa Saint Blaise in Cannes in the south of France. There, he quickly made contact with the leading monarchist politicians who were involved in anti-Republican plots.

Unsurprisingly, when on the evening of 17 July 1936 units of the Spanish Army in Morocco rebelled against the Second Republic, the coup d’état was enthusiastically welcomed by both Don Juan and his father. They avidly followed the progress of the military rebels on the radio, particularly through the lurid broadcasts of General Queipo de Llano. A group of Don Juan’s followers, who had been avid conspirators against the Republic, including Eugenio Vegas Latapié, Jorge Vigón, the Conde de Ruiseñada and the Marqués de la Eliseda, felt that it would be politically prudent for him to be seen fighting on the Nationalist side. He had already discussed the matter with his aide-de-camp, Captain Juan Luis Roca de Togores, the Vizconde de Rocamora. Don Juan left his home for the front for the first time on 31 July 1936, despite the fact that only the previous day Doña María de las Mercedes had given birth to their first child, a daughter, Pilar. His mother, Queen Victoria Eugenia, was present, having come to Cannes for the birth. To the delight of Don Juan’s followers, she declared: ‘I think it is right that my son should go to war. In extreme situations, such as the present one, women must pray and men must fight.’ Pleasantly surprised by this, they were, nevertheless, worried about the possible reaction of Alfonso XIII who was holidaying in Czechoslovakia. However, when Don Juan telephoned him, he too agreed enthusiastically, saying, ‘I am delighted. Go, my son, and may God be with you!’

The following day, 1 August, the tall and good-natured Don Juan duly crossed the French border into Spain in a chauffeur-driven Bentley, ahead of a small convoy of cars carrying his followers. They arrived in Burgos determined to fight on the Nationalist side. However, the rebel commander in the north, the impulsive General Emilio Mola, was in fact an anti-monarchist. Without consulting his fellow generals, he abruptly ordered the Civil Guard to ensure that Don Juan left Spain immediately. This incident inclined many deeply monarchist officers to transfer their long-term political loyalty from Mola to Franco.15

After his return to Cannes, the presence of important supporters of the Spanish military rebellion attracted the attention of local leftists. Groups of militants of the Front Populaire took to gathering outside the Villa Saint Blaise each evening and shouting pro-Republican slogans. Fearful for the security of his family – his wife was pregnant once more – Don Juan decided to move to Rome. His father was already resident there and the Fascist authorities would ensure that there would be no unpleasantness of the kind that had marred their stay in France. At first they lived in the Hotel Eden until, at the beginning of 1937, they moved into a flat on the top floor of the Palazzo Torlonia in Via Bocca di Leone. The palazzo was the home of Don Juan’s sister Doña Beatriz and Alessandro Torlonia.16

At the beginning of January 1938, Doña María de las Mercedes was coming to the culmination of her second pregnancy. However, when Don Juan was invited to go hunting, her doctor assured him that it was safe to go as the baby would not appear for at least another three weeks. Doña María was at the cinema with her father-in-law, Alfonso XIII, when her labour pains began. Juan Carlos was born at 2.30 p.m. on 5 January 1938 at the Anglo-American hospital in Rome. He was one month premature. When Doña María was taken to hospital, her lady-in-waiting, Angelita Martínez Campos, the Vizcondesa de Rocamora, called Don Juan back to Rome by sending him a telegram which read ‘Bambolo natto’ (Baby born). On receiving the telegram, he set off, driving so furiously that he broke an axle spring on his Bentley. Arriving before his son, Alfonso XIII played a trick. As he welcomed Don Juan, he held in his arms a Chinese baby boy – who had been born in an adjoining room to the secretary at the Chinese Embassy. Don Juan knew at once that the child was not his, yet, on seeing his own son, he confessed later, for a moment, he would have almost preferred the Chinese baby. Doña María, unlike most mothers, did not think her baby was the most beautiful creature on earth. She later recalled that, ‘The poor thing was a month premature and had big bulging eyes. He was ugly, as ugly as sin! It was awful! Thank God he soon sorted himself out.’ The blond baby weighed three kilograms. The earliest photographs of Juan Carlos were taken, not at his birth, but when he was already five months old.17 Despite his mother’s initial alarm, Juan Carlos did not remain ‘ugly’ for long. His good looks would always be a major asset – they would, indeed, be a major factor in his eventually winning the approval of Queen Frederica of Greece, his future mother-in-law.18

On 26 January 1938, the child was baptized at the chapel of the Order of Malta in the Via Condotti in Rome. The choice of the chapel was made because of its proximity to the Palazzo Torlonia, where the reception took place. The baptism ceremony was conducted by Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, then Secretary of State to the Vatican, and the future Pope Pius XII. At the christening, the baby Prince’s godmother was his paternal grandmother, Queen Victoria Eugenia. His godfather in absentia was the Infante Carlos de Borbón-Dos-Sicilias, his maternal grandfather. As a general in the Nationalist army, at the time engaged in the battle for Teruel, he was unable to travel to Rome. He was represented at the baptism by Don Juan’s elder brother, Don Jaime. Very few Spaniards were able to travel to Rome for the occasion and the birth of the Prince went virtually unnoticed even in the Nationalist zone of Spain.19

The boy was christened with the names Juan, for his father; Alfonso, for his paternal grandfather, the exiled King Alfonso XIII; and Carlos, for his maternal grandfather, Carlos de Borbón-Dos-Sicilias. Juan Carlos’s family and friends would, however, usually call him Juanito, at first because of his youth and later in order to distinguish him from his father. It was only after his emergence as a public figure that he began to use the name of Juan Carlos. There were, of course, political reasons behind the choice of the Prince’s public name. Don Juan told his lifelong adviser, the monarchisi intellectual, Pedro Sainz Rodríguez, that the choice was Franco’s. The idea may also have emanated from the conservative monarchist Marqués de Casa Oriol, José María Oriol, although the future King himself could not remember this with any certainty.20 ‘Juan Carlos’ would distinguish the Prince from his father, Don Juan, and perhaps ingratiate him with the ultra-conservative Car lists whose pretender always carried the name Carlos. The elimination of his middle name, Alfonso, would certainly have been to Franco’s liking since it was central to the Caudillo’s rhetoric that it was the misguided liberalism of Alfonso XIII that had rendered the Spanish Civil War inevitable.

Don Juan de Borbón continued to harbour a desire to take part in the Nationalist war effort. He had written to the Generalísimo on 7 December 1936 and respectfully requested permission to join the crew of the battlecruiser Baleares which was then nearing completion: ‘… after my studies at the Royal Naval College, I served for two years on the Royal Navy battlecruiser HMS Enterprise, I completed a special artillery course on the battleship HMS Iron Duke and, finally, before leaving the Royal Navy with the rank of Lieutenant, I spent three months on the destroyer HMS Winchester.’21 Although the young Prince promised to remain inconspicuous, not to go ashore at any Spanish port and to abstain from any political contact, Franco was quick to perceive the dangers both immediate and distant. If Don Juan were to fight on the Nationalist side, intentionally or otherwise he would soon become a figurehead for the large numbers of monarchists, especially in the Army, who, for the moment, were content to leave Franco in charge while waiting for victory and an eventual restoration of Alfonso XIII. There was the danger that the Alfonsists would become a distinct group alongside the Falangists and the Carlists, adding their voice to the political diversity that was beginning to come to the surface in the Nationalist zone. The execution of José Antonio Primo de Rivera, founder of the Falange, in a Republican prison had solved one problem, and Franco was now in the process of cutting down the Carlist leader, Manuel Fal Conde. He did not need Don Juan de Borbón emerging as a monarchist figurehead.

Franco’s response was a masterpiece of duplicity. He delayed some weeks before replying to Don Juan. ‘It would have given me great pleasure to accede to your request, so Spanish and so legitimate, to serve in our Navy for the cause of Spain. However, the need to keep you safe would not permit you to live as a simple officer since the enthusiasm of some and the officiousness of others would stand in the way of such noble intentions. Moreover, we have to take into account the fact that the place which you occupy in the dynastic order and the consequent obligations impose upon us all, and demand of you the sacrifice of desires which are as patriotic as they are noble and deeply felt, in the interests of the Patria … It is not possible for me to follow the dictates of my soldier’s heart and to accept your offer.’22 Thus, with apparent grace, he deflected a dangerous offer.

Franco also managed to squeeze considerable political capital out of so doing. He arranged for word to be circulated in Falangist circles that he had prevented the heir to the throne from entering Spain because of his own commitment to the future Falangist revolution. He also publicized what he had done and gave reasons aimed at consolidating his own position among the monarchists. ‘My responsibilities are great and among them is the duty not to put his life in danger, since one day it may be precious to us … If one day a King returns to rule over the State, he will have to come as a peace maker and should not be found among the victors.’23 The cynicism of such sentiments would be fully appreciated only after nearly four decades had elapsed, during which Franco dedicated his efforts to institutionalizing the division of Spain into victors and vanquished and failing to restore the monarchy. When the Baleares was sunk on 6 March 1938, Franco is said to have commented with an ironic smile, ‘And to think that Don Juan de Borbón wanted to serve on board.’24

In the meantime, in the autumn of 1936, believing that the military uprising would, if victorious, culminate in a restoration of the monarchy, Alfonso XIII had telegraphed Franco to congratulate him on his successes. In his suite in the Gran Hotel in Rome, the King kept a huge map of Spain marked with little flags with which he obsessively followed the progress of the rebel troops on various fronts.25 In his confidence that Franco would repay earlier favours by restoring the monarchy, he misjudged his man. Had he and his son been a little more suspicious, they might have been alarmed to note that the newly installed Head of State had already begun to comport himself as if he were the King rather than simply the praetorian guard responsible for bringing back the monarchy. With the support of the Catholic Church, which had blessed the Nationalist war effort as a religious crusade, Franco began to project himself as the saviour of Spain and the defender of the universal faith, both roles associated with the great kings of the past. Religious ritual was used to give legitimacy to his power as it had to those of the medieval kings of Spain. The liturgy and iconography of his regime presented him as a holy crusader; he had a personal chaplain and he usurped the royal prerogative of entering and leaving churches under a canopy.

The confidence in himself and his office generated by such ceremonial was revealed when Franco celebrated the first year of his Movimiento. His broadcast speech was, according to his cousin, entirely written by himself. He spoke in terms which suggested that he placed himself far higher than the Borbón family, as a providential figure, the very embodiment of the spirit of traditional Spain. He attributed to himself the honour of having saved ‘Imperial Spain which fathered nations and gave laws to the world’.26 On the same day, an interview with the Caudillo was published in the monarchist newspaper ABC. In it, he announced the imminent formation of his first government. Asked if his references to the historic greatness of Spain implied a monarchical restoration, he replied truthfully while managing to give the impression that this was his intention, ‘On this subject, my preferences are long since known, but now we can think only of winning the War, then it will be necessary to clean up after it, then construct the State on firm bases. While all this is happening, I cannot be an interim power.’

For Franco, and indeed many of his supporters within the Nationalist zone, the monarchy of Alfonso XIII was irrevocably stigmatized by its association with the constitutional parliamentary system. In his interview, he declared that, ‘If the monarchy were to be one day restored in Spain, it would have to be very different from the monarchy abolished in 1931 both in its content and, though it may grieve many of us, even in the person who incarnates it.’ This was profoundly humiliating for Alfonso XIII, all the more so coming from a man whose career he had promoted so assiduously.27

The Caudillo’s attitude to the exiled King, and by implication, to the Borbón family, was underlined in a harshly dismissive letter sent to Alfonso XIII on 4 December 1937. The King, having recently donated one million pesetas to the Nationalist cause, had written to Franco expressing his concern that the restoration of the monarchy seemed to be low on his list of priorities. The Generalísimo replied coldly, insinuating that the problems which caused the Civil War were of the King’s making and outlining both the achievements of the Nationalists and the tasks remaining to be carried out after the War. Expanding on his ABC interview, the Caudillo made it clear that Alfonso XIII could expect to play no part in that future: ‘the new Spain which we are forging has so little in common with the liberal and constitutional Spain over which you ruled that your training and old-fashioned political practices necessarily provoke the anxieties and resentments of Spaniards.’ The letter ended with a request that the King look to the preparation of his heir, ‘whose goal we can sense but which is so distant that we cannot make it out yet’.28 It was the clearest indication yet that Franco had no intention of ever relinquishing power, yet the epistolary relationship between Franco and the exiled King remained surprisingly smooth. (Indeed, in December 1938, Franco revoked the Republican edict that had deprived the King of his Spanish citizenship and the royal family of its properties.) Throughout the Civil War, after each victory, the Generalísimo had sent a telegram to Alfonso XIII and, in turn, received congratulatory messages from both the exiled King and his son. However, after the final victory, and the capture of Madrid, Franco had not done so. The outraged Alfonso XIII rightly took this to mean that Franco had no intention of restoring the monarchy.29

If the future of Alfonso XIII’s heir was unclear to Franco, even less certain was that of his grandson, Juan Carlos. For the first four and a half years of his life, the boy lived with his parents in Rome. Soon after his birth the family moved from the modest flat on the top floor of the Palazzo Torlonia in Via Bocca di Leoni to the four-storey Villa Gloria, at 112 Viale dei Parioli in the elegant Roman suburb of Parioli.30 This was a happy time for the Borbóns – a period during which it was possible to live as a relatively normal, as opposed to a royal, family. Juan Carlos’s younger sister Margarita was born blind on 6 March 1939. Even so, the degree of family warmth was limited. All three children were looked after by two Swiss nannies, Mademoiselles Modou and Any, under the supervision, not of their mother but of the Vizcondesa de Rocamora. The young Prince was often taken out for walks by his parents or by his nannies, sometimes to the Palazzo Torlonia, sometimes to the private park of the Pamphili family or to the park of Villa Borghese. Don Juan showed some affection for his eldest son, often carrying him in his arms when they visited Alfonso XIII at the Gran Hotel.

However, such signs of warmth were rare. The young Prince was soon being schooled in the harsh lesson that his central purpose in life was to contribute in some way to the mission of seeing the Borbón family back on the throne in Spain. Don Juan had already started to make demands that the child found difficult to meet. Miguel Sánchez del Castillo (a film actor working in Rome at the time) recalls that, on one occasion, Juan Carlos was given a cavalry uniform as a present from several Spanish aristocratic ladies. ‘An Italian photographer spent over an hour taking pictures of him. Don Juan Carlos, who was only four years old at the time, endured having to stand to attention on a table. When they finally took him to the kitchen and one of his nannies took his boots off, his feet had been rubbed raw, because the boots were too small for him. That is when he shyly started to cry. I later learnt that his father had taught him from a very young age that a Borbón cries only in his bed.31