Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «The Silent Fountain»

VICTORIA FOX divides her time between Bristol and London. She used to work in publishing and is now the author of six novels.

For Joanna Croot

Contents

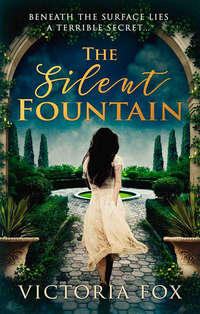

Cover

About the Author

Title Page

Dedication

PROLOGUE

PART ONE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

PART TWO

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE

CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX

CHAPTER THIRTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER THIRTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER THIRTY-NINE

CHAPTER FORTY

CHAPTER FORTY-ONE

CHAPTER FORTY-TWO

CHAPTER FORTY-THREE

CHAPTER FORTY-FOUR

CHAPTER FORTY-FIVE

CHAPTER FORTY-SIX

CHAPTER FORTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER FORTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER FORTY-NINE

CHAPTER FIFTY

CHAPTER FIFTY-ONE

CHAPTER FIFTY-TWO

EPILOGUE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Copyright

PROLOGUE

Italy, Summer 2016

It was always the same dream, and every time she saw it coming. She knew where it began. A bright light, gathering pace from a sheet of dark. A lucid thought, a picture more real than any she could fathom in waking hours. Afraid to look but more afraid to resist, she stepped towards the light, arms open, weak, and she knew it was a trick, but suddenly there she was, blissful, forgetting, her lips on his forehead, his soft skin and his smell; she could capture it now, so many years later and on the other side of consciousness. His hair, the warmth of his body, they were locked away in the deepest parts inside her, still intact despite the storms that place had weathered.

She knew where it ended. He shouldn’t have spoken; he shouldn’t have asked.

Don’t leave me. Come with me. I’m waiting.

I’ll catch you. We’ll be together again.

The water, still and cool and silver and quiet. Inviting. Come with me…

I’m waiting.

*

The woman wakes with a jolt. Her bedclothes are bunched and damp with sweat. It takes a moment to surface, the weight of water all around, pressing down. The air is tight in her lungs.

Adalina, the maid, comes in, opens the shutters and welcomes the day.

‘There, signora, that’s better. How did you sleep?’

Quick, efficient, the maid sets down the breakfast tray, pillows plumped, sheets pulled tight. And then the rainbow of pills, a box of medicines laid out like sweets, as if the colours make it better, make her want to take them, willingly.

The woman coughs; it is like bringing something solid up, a ball of wire.

There is blood on her handkerchief: a spray of bright dots, the worst omen. It won’t be long now. She folds it into her clenched palm. Adalina pretends not to see.

‘I…’ The woman’s mind is empty. Her tongue is swollen, a stranger to her mouth, as if she is the one who has swallowed the swamp.

‘Open the window,’ she says.

A flick of the wrist; the sun spills in. She can see the tips of the cypress trees, twelve fingers pointing towards the sky. She used to think he was up there, believe in useless comforts, but she doesn’t any more. He isn’t in the sky. He isn’t in the clouds. He isn’t even in the ground. He is inside her. Calling her, needing her.

Air. Warmth. Birdsong. She receives the scent of her budding gardens, can picture the roses on the arches beginning to bloom, pink and sweet, and the lavender and chives clustered against their high chalk walls, bursting white and lilac. How easily the outside creeps in. How easily it bridges that line, as fast and fluid as rain. How easily she ought to be able to do the same, one step, one foot in front of the other, that was all it took, that was what the doctors said. The same as trespassing into those rooms, those wings, that have been locked in dust for decades: unbearable now.

‘Such a beautiful house,’ they whispered, in the village, in the city, across the oceans for all she knew. ‘How tragic that she’s the way she is… Still, I suppose one can understand it, after…you know…’

‘The girl is due at midday,’ says Adalina, rattling the pills into a plastic receptacle at the same time as pouring the tea, as if one were no more unusual a feast than the other. ‘I’ve checked the airport and there are no delays. Will you be able to greet her? She’d like to meet you, I’m sure.’

The woman glances away. She watches her pale hands resting like a corpse’s on the sheet, the bloodstained handkerchief hidden there: a terrible key to a terrible secret. Her wrists are brittle, her nails short, and she thinks how old they look.

When did I grow old?

She shakes her head. ‘I shall stay in bed,’ she says. Just like every other day. This house has too many corners, too many secrets, crooked with shadows and silence. ‘And I shouldn’t like any disturbances. You can settle her in, I’ve no doubt.’

‘Very well, signora.’

She swallows the pills; Adalina retreats, her face a mask of discretion. The maid has no need to voice her feelings, but it is no matter. Let them be disappointed. Let them say, ‘She should make the effort. The girl’s come a long way.’ Let them think what they wish. Only she understands the impossibility of it.

Besides, she doesn’t want the girl here. She has never wanted her. The help knows too much, asks too many questions; they make it their business to pry.

What choice does she have? Adalina cannot manage. The castillo is enormous. They cannot do it alone.

This time, the truth is hers to keep. No one is getting to it.

She closes her eyes, drowsy, her pills beginning to take effect. On the cusp of sleep, she hears his voice again. Calling her from the water, the orange sun setting.

Come with me. I’ll catch you. I’m waiting.

She falls, her arms open wide.

PART ONE

CHAPTER ONE

London

One month earlier

They say you can never love again like you love the first time. Maybe it’s the heart changing shape, unable to resume its original form. Maybe it’s the highs made more acute for their novelty and strangeness. Or maybe it’s the soul that grows wise. It learns that the risks aren’t worth taking. It learns to hurt, and in doing so protect itself.

There is consolation in this, I think, as I thread through the crowds on the Underground – commuters in rush hour, plugged into their phones; tourists checking maps and getting stuck by the ticket machines; couples kissing on the escalators – the certainty that whatever happens, wherever I end up, I will never again go through what I have been through before. We are shepherded from the Northern Line up into fresh air, where the blare and hum of the city bleeds past in myriad lights and colour. I pass a group of girls heading out for the night; they must be my age, I suppose, late twenties, but the gulf between us is yawning. I look at them as if through a window, remembering when I was like them, frivolous, carefree, naïve – how it feels to stand on the brink of the world, no mistakes made, at least none so irrevocable as mine.

One thing I love about London is the anonymity. So many people and so many lives, and it’s an irony that I came here to be noticed, to be someone, yet it was at the centre of everything that I achieved invisibility. I will miss the anonymity, when they find out. I will look back on it as a cherished prize, never to be regained once lost.

I catch the bus, staring out of the window at rapidly darkening streets. Across the aisle a guy in glasses reads the Metro, its front page belting the headline: MURDERER HELD: COPS CATCH CAR BOOT KILLER. I shiver. Will I earn my own headline, one day soon? What will they say about me? I see my name, plain old Lucy Whittaker, in the round, friendly handwriting that as a child adorned my homework, my thank you letters, the birthday cards I wrote to my friends, then latterly the typed headers on my job applications, become all at once horrid and threatening, a name to be appalled by. People I once knew will say, ‘Not that Lucy Whittaker? But she’s far too quiet, far too shy, she wouldn’t do anything like that…’

But I did, I think. I did do something like that.

We come to my stop and I step out into the evening, wrapping my coat tight as the wind picks up. I keep my head down, the plastic box clamped under my arm.

My phone beeps. For a stupid moment I think it’s him, and I despise myself for how swiftly I dive into my pocket, hand trembling and hope sinking as I realise it’s not. It’s Bill, my flatmate. Belinda’s her name, but she never liked it.

When are you home? I have wine Xxx

I’m almost there so it isn’t worth replying. My walk slows. As ever when I open my messages I find my eyes drawn to his, our chains of all-night conversations, flirty, thrilling, the way my heart danced every time that screen lit up at two in the morning. I should delete them, but I can’t. It’s as if wiping them will erase any proof that it happened in the first place. That before the bad, there was good. There was, before. It was good. What happened, there was a reason for it…

Don’t be an idiot. There is no reason. Nothing justifies what you did.

And of course he wouldn’t be in touch. He’d never be in touch. It was over.

I turn on to our street. Unlocking the front door, I see Bill still hasn’t got the hang of sorting through the post, so I scoop the scattered envelopes off the floor and divide them between the flats, before taking our own upstairs. Bill still hasn’t got the hang of a lot of shared living, I’ve noticed, like replacing loo roll or putting out the recycling every once in a while. I don’t mind, though. She’s been my best friend since we could walk; she’s been with me through it all and she’s still with me now, the only one who knows the brutal truth and even then she didn’t walk away, when she really could have. When she should have. That’s why I don’t care about the recycling.

‘How was it?’ She’s waiting when I go in, drink poured, TV on, some rehash of a talent show, and she drains the volume when I lift my shoulders.

‘As expected.’ I set the box down and consider, as I had back at the office, how five years can be compressed into five minutes’ packing. Some old notecards, my desk calendar, a sangria-bottle fridge magnet from Portugal sent to me by a client.

‘No fanfare, then?’ Bill gives me a hug and a squeeze. The squeeze brings up tears but I blink them away. ‘It’s your own fault,’ Natasha, his deputy, had hissed, as I’d slunk towards the exit of Calloway & Cooper, trying to ignore the stares that followed, fascinated and horrified, like traffic crawling past a pile-up.

Natasha has had it in for me from day one. My theory? She’s in love with him. As his Commercial Director she was widely regarded as his second in command – but then I came along, usurping her as the closest person to him, his PA, and I know she tried to get someone else into the role because Holly in Accounts told me. Only, Natasha didn’t win. I did. And I think she couldn’t handle the fact that, for a second there, towards the end, before it all went wrong, it looked as if he might have loved me back. When it blew up, all her Christmases came at once. Natasha was delighted to see me go, and couldn’t believe her luck at the circumstances that drove me to it.

I try a laugh but it dies in my throat. ‘No fanfare,’ I agree, and grab the wine and sink it in one. Bill refills me. I want to smoke a cigarette, but I’m trying to give up. Great timing, Lucy, I think. Who cares now, if you live or die? But that is melodrama, and I annoy myself for thinking it. Instead, I keep focused on the alcohol. If I keep drinking, I’ll get numb, and if I get numb, I won’t feel anything. I won’t feel his touch on my cheek, his kiss on my mouth, my neck…

‘Come on,’ says Bill, with an uncertain smile. ‘It’s finished.’

‘Is it?’

‘You never have to see those people again. You never have to see him again.’

One thing Bill doesn’t understand, and I can’t find the words to explain: I have to see him again. Even after everything, how I should want to run as far away from him as I can, I’m as addicted to him as I was the first day. Inappropriate isn’t the half of it. I read that the funeral happened this morning, in a cemetery south of the river, and I can’t stop thinking of him, rigid with grief, those grey, beautiful eyes set hard on the ground, the cool drizzle settling on the shoulders of his coat, a coat I’d once warmed my hands in on a cold night on Tower Bridge, and he’d kissed the tip of my nose. How I long to put my arms around him now, tell him I am sorry and that I miss him. When what I should be feeling is guilt, burning guilt, shame and disgrace and all those things, and I do feel them, every day I do, but at the same time I can’t forget the power of us. We don’t belong with any of that confusion or chaos or sadness.

‘…You could consider it, you know, if that’s what you want.’

Bill is looking at me gently, waiting for a response.

‘What? I was miles away.’

‘Freddy’s sister’s boyfriend,’ she says, presumably for the second time. ‘He’s just come back from Italy – that language course he went on in Florence?’ Bill prompts me and to placate her I nod, even though I have no memory of this (so much over the last twelve months has dissolved to insignificance; I can’t even remember who Freddy is – someone Bill works with?). ‘While he was out there,’ she goes on, ‘he made friends with this girl who was looking after a house on weekends. Well, I say house, but it’s more like a mansion. In fact Freddy said it was this giant pile, and someone famous lives there but the friend never met her, and anyway, this woman’s a recluse and never goes out.’ Bill slumps down on the sofa. ‘Sounds intriguing, right? Like the start of a novel.’ There’s something behind the cushion and she reaches to retrieve it. ‘Hey,’ her face lights up, ‘I found 50p!’

I frown. ‘What’s this got to do with me?’

Bill crosses her legs. ‘The girl got fired and they’re looking for someone to replace her. All very hush-hush… apparently they’d never advertise. The woman sounds a bit weird, sure, but how hard could it be? Dusting a few shelves, sweeping the floor…’ She makes a face and I wonder if her knowledge of looking after a house extends beyond Cinderella. ‘Then getting to sunbathe all day with some sexy Italian you’ve met in the city? I’d do it myself if I didn’t have to go to work on Monday.’

I’m wary. ‘What are you suggesting?’

‘Think about it, Lucy.’ Her voice softens. ‘Since this thing happened, you’ve been desperate to get away. You haven’t stopped talking about it, how you can’t stay here. Look,’ she says, standing, ‘I want to show you something.’ She steers me to the mirror in the hall. ‘Tell me what you see,’ she says. ‘Honestly.’

It doesn’t help that strewn across the wall are pictures from the days before. Nights out with Bill, holidays with friends, a bungee jump I did on my twenty-fifth birthday, after I finally broke free from home and started building a future for myself. That’s how I see it, this looming punctuation mark in the story of my life, isolating the years preceding him and the lonely days after, creeping into weeks, and I was a different girl then: bright, hopeful, lucky, alive. What do I see now? A dull ache in my eyes, my skin wan with nights spent thinking and wondering and turning over what ifs, hollowness in my cheeks, and sadness, mostly sadness.

‘I don’t want to do this,’ I say, shrugging free.

‘You’re not you, Lucy. This isn’t you.’

‘What do you expect?’ I round on her, not keen on starting a fight but unable to help it. I need to shout at someone, to be angry, because I’m sick of being angry with myself. ‘Her funeral was today – did you know that? And I’m supposed to leave everything behind, the mess I’ve made, and swan off to Italy for a holiday?’

‘It’s not a holiday,’ says Bill, ‘it’s a job. And, let’s face it, you need one.’

‘I’ll manage.’

‘What about the press?’ She’s silenced me now. ‘What about when they’re blowing up your phone, or when they’re smashing down the door and you’re afraid to go outside? Do you think he’s going to defend you, then? He doesn’t care, Lucy – he doesn’t give a crap about you. He’ll put it all on you and then how’s it going to look?’

‘Don’t say those things about him.’

‘Fine, we won’t go there. You know how I feel. My point is: this is your chance. I mean, talk about timing! You could leave it all, come back once it’s settled.’

‘How’s it getting settled?’

‘It will. Everything fades eventually.’

I snort. But my back is to her, so she can’t see my face.

‘What’s the alternative?’ Bill asks.

I think about the alternative. Fronting the world, my family, my face splashed across the nation’s papers, quotes taken out of context, painted to be someone I’m not.

Would he break his silence then? Would he reach to help me; would he stand at my side? Bill’s words sting: He doesn’t care. He doesn’t give a crap about you.

Her question hangs unanswered. It’s all I can do to turn to my friend, the fight gone out of me. ‘I’m sorry,’ I say, meaning it, and she shakes her head like it doesn’t matter. ‘I just…’ A well swims up my chest, threatening to spill over, and my voice goes funny. ‘I’m just not coping.’

‘I know.’ Bill hugs me. ‘Please promise me you’ll consider it?’

In bed that night, I do. Lying awake, pretending to myself that I’m not waiting for my phone to light up, I listen to the passing hum of traffic that gradually dwindles to quiet, before, at around two, I finally fall asleep. The last thing I think of, for the first time in months, isn’t him. It’s a house, surrounded by cypress trees, deep in the middle of the Italian hills. As I walk towards dreams, I’m in a tangled rose garden. Something unseen beckons me, a shadow slipping in and out of sunlight.

I come to a fountain, quiet and glittering silver.

I look in the pool at my reflection.

It takes a moment to recognise myself. For a heartbeat, it’s not me I see.

CHAPTER TWO

Italy

My train arrives in Florence three weeks later. It’s happened quickly – the best way, Bill tells me, to counter my usual inclination to overthink everything – and back in London I barely had time to make my decision, take a short phone interview with the owner of the house, renew my passport and get my papers sorted before Bill was yanking my suitcase from the top of the wardrobe and encouraging me to fill it.

I suspect she’s right. Without getting caught up in momentum, there would have been too many opportunities to stall, to opt out, to say that something this reckless and ill thought through really wasn’t me. Then again, what was? What made Lucy Whittaker? I had forgotten. I had lost her – and I wasn’t going to find her hanging around in our Camden flat, jobless and trapped in the past.

‘Go.’ Bill held me by the shoulders when she said goodbye. ‘Don’t think about anything here. Be happy, Lucy. Let go. Fall in love with Italy.’

My first impressions of the city aren’t great. Santa Maria Novella station is hot and crowded; I’m on the receiving end of a wave of distrustful glances when I kneel to sort through my bag because a bottle of shampoo leaked over my clothes on the flight to Pisa, and, as I’m trying to fathom the bus timetable to get me into the centre, a guy falls into me from behind, apologises – ‘Mi scusi, signora…’ – and seconds later I realise fifty euros are missing from the back pocket of my jeans. But when we enter the streets that I recognise, see the bronzed, proud hood of the Duomo with its decorative Campanile, all that marble shimmering pink and white in the sunshine, I forget my plight for a moment and succumb to Florence’s spell. Locals speed past on mopeds, exploding dust on cobbled streets; pizzerias open their shutters for lunch, red and white checked tablecloths being laid on a baking-hot terrace while waiters smoke idly, breaking before service; tourists wander past in sunhats, licking pink gelato from cornets; a dog drinks from a pipe on the Via del Corso. We said we’d come together, once, he and I. He wanted to bring me, promised we’d take a boat out on the Arno, eat spaghetti and drink wine; we’d stroll around the Uffizi, fall asleep in the afternoon in the Boboli Gardens. ‘Forget Paris – Florence is the most romantic city in the world.’

The bus stops and I have to move, as if physical distance might stow the memories away, as if I can leave him here in the empty seat next to mine.

It’s a quick change to take the bus to Fiesole. I’m ready to get there now, see the house and meet its proprietor, fill my hours with tasks that have nothing to do with him or my life at home. My dad wanted to know what on earth I was doing. ‘Italy?’ he interrogated. ‘Why? What about work? You left your job, Lucy? What happened?’

My sisters were the same. Sophie called from a fashion shoot to tell me I was walking away from the best role I’d ever have. Helen emailed from the luxury of her Thamesside apartment to brag about her lawyer fiancé being made partner at his firm, then saying as an afterthought that my ‘mini-break’ in Florence should be fun, but why wasn’t I going with a boyfriend? As for Tilda, I haven’t heard from her in weeks. She’s scuba diving in Barbados, with a surfer named Marc. Unlike the others, Tilda didn’t go to university. That was probably my biggest battle, as the eldest, trying to run my own life while taking the place of our mum: the endless months of Tilda stalemate, attempting to convince her that I knew better when maybe I didn’t.

The years between us are nothing significant, the kind of gap an ordinary family wouldn’t think twice about. But, for us, they were everything. They marked me as an adult before my time, and my sisters as children when really they could have been more. Helping to raise them was just what happened, a natural choice – no, not a choice, a given, but never one I resented. My dad couldn’t do it alone, and my sisters were too young to understand what it meant to be without their mother. It broke my heart that she would never see them pass their first exams, meet their first boyfriends, make and break those intense alliances exclusive to teenage girls, ever see them engaged or married or with children of their own – and of course much of this applied to me, although I never dwelled on that. I’m proud of the role I took on, but sometimes I wonder what might have been if I’d had the chance to have normal teenage years, be a normal girl. Then, maybe, my first love and first mistakes would have been less devastating than the ones that brought me here.

As the Tuscan countryside rolls past, winding and winding up from Florence through flame-shaped cypress trees and golden fields dotted with heat-drenched villas, I consider if what I’m doing here is exactly what I did after Mum died. Running without moving. Building a wall of practical tasks, tangible end goals, things I can get my hands dirty with, to avoid feeling… Feeling what? Just feeling.

None of my sisters knows about what happened. It’s not their fault – I haven’t told them. I’ve never told my family anything about my life, and the more personal it is, the more precious and the less willing I am to share it. Because I’ve always been the reliable, responsible one, and I’ve always looked after myself. I’ve never needed them for comfort or reassurance, not like they’ve needed me.

They’ll find out soon. Everyone will.

And then what?

The question echoes in my mind, unanswered and unanswerable.

‘Piazza Mino,’ the driver calls, as the bus jolts to a stop. I haul my bag. There’s no GPS signal so I consult the map I printed before I left, and begin walking.

The path is scorching. My muscles burn as I travel uphill, bright sun drenching the backs of my legs. I enjoy the air in my lungs, the sheen of sweat that gathers on my lip. These things make me feel alive, remind me I’m still breathing.

Thirty minutes later, I’m hot and thirsty. I’ve long since left the village behind and entered an ochre landscape, fields of maize and barley rolling wide on both sides, as I climb dusty lanes and take refuge in the occasional dapple of the olive groves. Silver-backed leaves offer flickering shade and I rest a while beneath them, drinking from my bottle and starting to feel faintly worried that I shall never find this place.

Then, beneath the smell of almonds and the sweet hint of blue-black grapes, a brighter scent: I spy a crop of lemon trees over the hill, running as far as the eye can see, each richly laden with yellow fruit. Squinting against the sun, I step up to the wall. On the horizon, melting to a blur in the fragrant heat, there is a building. It is enormous, its façade the colour of overripe peaches and with a sprawling, age-damaged terracotta roof. There are turrets, and the dark outline of arched windows.

I look at the map. This is it. The Castillo Barbarossa.

The road winds in a great loop around the estate and, making a decision, I topple my bag over the wall and opt for the shortcut. If the size of the castillo is anything to go by, it owns this grove and several other hectares beyond. I pick my way among the fruit trees. The lemons make me want to drink. I picture the owner of the house welcoming me with a refreshing glass, but then I remember what Bill told me. I remember what the woman was like on the phone – that strange, stilted interview, disconcertingly brief and undetailed, as if she hadn’t wanted to speak to me at all and was doing so under duress. I was relieved to know she wasn’t Italian, as I was planning to learn the language on the job; instead, I met a hint of an American accent, blunted by years in Europe and carrying with it the sharp plumminess of wealth and power. Afterwards, I told myself the connection had been bad. It would be better when we met in person. The follow-up message I received to tell me I’d been successful was testament that I had passed muster. There was nothing to doubt.

As I come closer to the house, dwarfed now by its massive proportions, the sun slips behind a cloud. The place looks ancient, and curiously un-lived-in, its wooden shutters bolted, its creamy walls more cracked and dilapidated than they had appeared from a distance. A sprawl of dark green creepers climbs like a skin rash up one side. I frown, checking the map again, then fold it and put it in my pocket.

Wide stone steps descend from the entrance, spilling on to a gravel shelf that rolls on to a second, then a third, then a fourth, at one time grand and verdant but now left to decades of neglect, their oval planters crumbling and full of dead, twisted things. At the helm is a fountain, long defunct, a stone shape rising from its basin that I cannot decipher from here. I feel as if I have seen the fountain before, though of course that is impossible. I emerge on to the drive and when I pass the fountain I do not want to look at it. Instead, I stop at the door and raise my hand.