Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «Enemies Within: Communists, the Cambridge Spies and the Making of Modern Britain»

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2018

Copyright © 2018 Richard Davenport-Hines

Cover design by Kate Gaughran

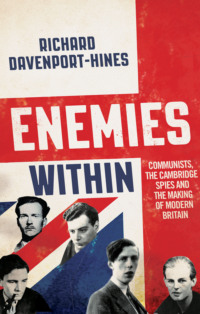

Cover images © Tallandier/bridgemanimages.com; © Keystone/Getty Images; © Lytton Strachey/Frances Partridge/Getty Images; © Keystone/Getty Images (photographs); Shutterstock.com (background texture & flag)

Richard Davenport-Hines asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007516674

Ebook Edition © January 2018 ISBN: 9780007516681

Version: 2017-12-11

Dedication

With love for † Rory Benet Allan

With gratitude to the Warden and Fellows of All Souls

Epigraph

The lie is a European power.

FERDINAND LASSALLE

Great is the power of steady misrepresentation.

CHARLES DARWIN

No great spy has been a short-term man.

SIR JOHN MASTERMAN

Men are classed less by achievement than by failure to achieve the impossible.

SIR ROBERT VANSITTART

Men go in herds: but every woman counts.

BLANCHE WARRE-CORNISH

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Author’s Note

Glossary

Illustration Credits

Aims

PART ONE: Rules of the Game

Chapter 1: The Moscow Apparatus

Tsarist Russia

Leninist Russia

Stalinist Russia

The Great Illegals

Soviet espionage in foreign missions

The political culture of everlasting distrust

Chapter 2: The Intelligence Division

Pre-Victorian espionage

Victorian espionage

Edwardian espionage

Chapter 3: The Whitehall Frame of Mind

The age of intelligence

The Flapper Vote

Security Service staffing

Office cultures and manly trust

Chapter 4: The Vigilance Detectives

The uprising of the Metropolitan Police

Norman Ewer of the Daily Herald

George Slocombe in Paris

The Zinoviev letter and the ARCOS raid

MI5 investigates the Ewer–Hayes network

Chapter 5: The Cipher Spies

The Communications Department

Ernest Oldham

Hans Pieck and John King

Walter Krivitsky

Chapter 6: The Blueprint Spies

Industrial mobilization and espionage

Propaganda against armaments manufacturers

MI5 watch Wilfrid Vernon

MI5 watch Percy Glading

The trial of Glading

PART TWO: Asking for Trouble

Chapter 7: The Little Clans

School influences stronger than parental examples

Kim Philby at Westminster

Donald Maclean at Gresham’s

Guy Burgess at Eton and Dartmouth

Anthony Blunt at Marlborough

Chapter 8: The Cambridge Cell

Undergraduates in the 1920s

Marxist converts after the 1931 crisis

Oxford compared to Cambridge

Stamping out the bourgeoisie

Chapter 9: The Vienna Comrades

Red Vienna

Anti-fascist activism

Philby’s recruitment as an agent

Chapter 10: The Ring of Five

The induction of Philby, Maclean and Burgess

David Footman and Dick White

The recruitment of Blunt and Cairncross

Maclean in Paris

Philby in Spain: Burgess in Section D

Goronwy Rees at All Souls

Chapter 11: The People’s War

Emergency recruitment

The United States

Security Service vetting

Wartime London

‘Better Communism than Nazism’

‘Softening the oaken heart of England’

Chapter 12: The Desk Officers

Modrzhinskaya in Moscow

Philby at SIS

Maclean in London and Washington

Burgess desk-hopping

Blunt in MI5

Cairncross hooks BOSS

Chapter 13: The Atomic Spies

Alan Nunn May

Klaus Fuchs

Harwell and Semipalatinsk

Chapter 14: The Cold War

Dictaphones behind the wainscots?

Contending priorities for MI5

Anglo-American attitudes

A seizure in Istanbul

Chapter 15: The Alcoholic Panic

Philby’s dry martinis

Burgess’s dégringolade

Maclean’s breakdowns

The VENONA crisis

PART THREE: Settling the Score

Chapter 16: The Missing Diplomats

‘All agog about the two Missing Diplomats’

‘As if evidence was the test of truth!’

States of denial

Chapter 17: The Establishment

Subversive rumours

William Marshall

‘The Third Man’

George Blake

Class McCarthyism

Chapter 18: The Brotherhood of Perverted Men

The Cadogan committee

‘Friends in high places’

John Vassall

Charles Fletcher-Cooke

Chapter 19: The Exiles

Burgess and Maclean in Moscow

Philby in Beirut

Bestsellers

Oleg Lyalin in London

Chapter 20: The Mole Hunts

Colonel Grace-Groundling-Marchpole

Robin Zaehner and Stuart Hampshire

Anthony Blunt and Andrew Boyle

‘Only out for the money’

Maurice Oldfield and Chapman Pincher

Envoi

Picture Section

Notes

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Richard Davenport-Hines

About the Publisher

Author’s Note

In MI5 files the symbol @ is used to indicate an alias, and repetitions of @ indicate a variety of aliases or codenames. I have followed this practice in the text.

Glossary

| Abwehr | German military intelligence, 1920–45 |

| active measures | Black propaganda, dirty tricks |

| agent | Individual who performs intelligence assignments for an intelligence agency without being an officer or staff member of that agency |

| agent of influence | An agent who is able to influence policy decisions |

| ARCOS | All Russian Co-operative Society, London, 1920–7 |

| asset | A source of human intelligence |

| BSA | Birmingham Small Arms Company |

| C | Chief of the Secret Intelligence Service |

| case officer | An officer of an intelligence agency responsible for operating a particular agent or asset |

| Cheka | Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counter-Revolution and Sabotage, USSR, 1917–22 |

| CIA | Central Intelligence Agency, USA, 1947– |

| CID | Committee of Imperial Defence, London, 1902–39 |

| CIGS | Chief of the Imperial General Staff, London, 1909–64 |

| Comintern | Third Communist International, USSR, 1919–43 |

| CPGB | Communist Party of Great Britain, 1920–91 |

| CPUSA | Communist Party of the United States of America, 1921– |

| cut-out | The intermediary communicating secret information between the provider and recipient of illicit information; knowing the source and destination of the transmitted information, but ignorant of the identities of other persons involved in the spying network |

| dead drop | Prearranged location where an agent, asset or case officer may leave material for collection |

| double agent | Agent cooperating with the intelligence service of one nation state while also working for and controlled by the intelligence or security service of another nation state |

| DPP | Directorate of Public Prosecutions, UK |

| DSO | Defence Security Officer, MI5 |

| FBI | Federal Bureau of Investigation, US law enforcement agency, 1908– |

| FCO | Foreign & Commonwealth Office, 1968– |

| FO | Foreign Office |

| Fourth Department | Soviet military intelligence, known as the Fourth Department of the Red Army’s General Staff, 1926–42 |

| Friend | Source |

| GC&CS | Government Code & Cypher School, 1919–46 |

| GCHQ | Government Communications Headquarters, 1946– |

| GPU | State Political Directorate, USSR, 1922–3 |

| GRU | Soviet military intelligence, 1942–92 |

| HUAC | House Un-American Activities Committee, USA, 1938–69 |

| HUMINT | human intelligence |

| illegal | Officer of an intelligence service without any official connection to the nation for whom he is working; usually with false documentation |

| INO | foreign section of Cheka and its successor bodies, USSR, 1920–41 |

| intelligence agent | An outside individual who is used by an intelligence service to supply information or to gain access to a target |

| intelligence officer | A trained individual who is formally employed in the hierarchy of an intelligence agency, whether serving at home or abroad |

| legal | Intelligence officer serving abroad as an official or semi-official representative of his home country |

| MGB | Ministry for State Security, USSR, 1946–53 |

| MVD | Ministry of Internal Affairs, USSR, 1953–4 (as secret police) |

| negative vetting | background checks on an individual before offering her or him a government job |

| NKGB | People’s Commissariat of State Security, February–July 1941 and 1943–6 |

| NKVD | People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (responsible for state security of Soviet Union 1934–February 1941 and July 1941 to 1943) |

| NUPPO | National Union of Police and Prison Officers, 1913–20 |

| OGPU | Combined State Political Directorate, USSR, 1923–34 |

| OSINT | open source intelligence |

| OSS | Office of Strategic Services, Washington, 1942–5 |

| PCO | Passport Control Officer: cover for SIS officers in British embassies and legations |

| positive vetting (PV) | The exhaustive checking of an individual’s background, political affiliations, personal life and character in order to measure their suitability for access to confidential material |

| principal | Intelligence officer directly responsible for running an agent or asset |

| protective security | Security to protect personnel, buildings, documents, communications etc. involved in classified material |

| PUS | Permanent Under Secretary |

| PWE | Political Warfare Executive, UK |

| rezident | Chief of a Soviet Russian intelligence station, with supervisory control over subordinate intelligence personnel |

| rezidentura | Soviet Russian intelligence station |

| ROP | Russian Oil Products Limited |

| SIGINT | Intelligence from intercepted foreign signals and communications. Human intervention is needed to turn the raw product into useful intelligence |

| SIME | Security Intelligence Middle East |

| SIS | Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), 1909– |

| SS | Security Service (MI5, under which name it was founded in 1909), 1931– |

| tradecraft | Acquired techniques of espionage and counterintelligence |

| vorón | Literally ‘raven’: a male Russian operative used for sexual seduction |

Illustration Credits

– Sir Robert Vansittart, head of the Foreign Office. (Popperfoto/Getty Images)

– Cecil L’Estrange Malone, Leninist MP for Leyton East. (Associated Newspapers/REX/Shutterstock)

– Jack Hayes, the MP whose detective agency manned by aggrieved ex-policemen spied for Moscow. (© National Portrait Gallery, London)

– MI5’s agent M/1, Graham Pollard. (Esther Potter)

– MI5’s agent M/12, Olga Gray. (Valerie Lippay)

– Percy Glading, leader of the Woolwich Arsenal and Holland Road spy ring. (Keystone Pictures USA/Alamy Stock Photo)

– Wilfrid Vernon, the MP who filched aviation secrets for Stalinist Russia and spoke up for Maoist China. (Daily Mail/REX/Shutterstock)

– Maurice Dobb, Cambridge economist. (Peter Lofts)

– Anthony Blunt boating party on the River Ouse in 1930. (Lytton Strachey/Frances Partridge/Getty Images)

– Moscow’s talent scout Edith Tudor-Hart. (Attributed to Edith Tudor-Hart; print by Joanna Kane. Edith Tudor-Hart. National Galleries of Scotland / Archive presented by Wolfgang Suschitzky 2004. © Copyright held jointly by Peter Suschitzky, Julie Donat and Misha Donat)

– Pall Mall during the Blitz. (Central Press/Getty Images)

– Andrew Cohen, as Governor of Uganda, shares a dais with the Kabaka of Buganda. (Terence Spencer/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images)

– Philby’s early associate Peter Smolka. (Centropa)

– Alexander Foote, who spied for Soviet Russia before defecting to the British in Berlin and cooperating with MI5. (Popperfoto/Getty Images)

– Igor Gouzenko, the Russian cipher clerk who defected in 1945. (Bettmann/Getty Images)

– Donald Maclean perched on Jock Balfour’s desk at the Washington embassy, with Nicholas Henderson and Denis Greenhill. (Popperfoto/Getty Images)

– Special Branch’s Jim Skardon, prime interrogator of Soviet spies. (Associated Newspapers/REX/Shutterstock)

– Lord Inverchapel appreciating young American manhood. (Photo by JHU Sheridan Libraries/Gado/Getty Images)

– A carefree family without a secret in the world: Melinda and Donald Maclean. (Photo by Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images)

– Dora Philby and her son in her Kensington flat. (Photo by Harold Clements/Express/Getty Images)

– Philby’s wife Aileen facing prying journalists at her front door. (Associated Newspapers/REX/Shutterstock)

– Alan Nunn May, after his release from prison, enjoys the consumer durables of the Affluent Society. (Keystone Pictures USA/Alamy Stock Photo)

– The exiled Guy Burgess. (Popperfoto/Getty Images)

– John Vassall. (Trinity Mirror/Mirrorpix/Alamy Stock Photo)

– George Blake. (Photo by Central Press/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

– George Brown, Foreign Secretary. (Clive Limpkin/Associated Newspapers /REX/Shutterstock)

– Richard Crossman. (Photo by Len Trievnor/Daily Express/Getty Images)

– Daily Express journalist Sefton Delmer. (Photo by Ronald Dumont/Express/Getty Images)

– Maurice Oldfield of SIS – with his mother and sister outside Buckingham Palace. (©UPP/TopFoto)

Aims

In planning this book and arranging its evidence I have been guided by the social anthropologist Sir Edward Evans-Pritchard. ‘Events lose much, even all, of their meaning if they are not seen as having some degree of regularity and constancy, as belonging to a certain type of event, all instances of which have many features in common,’ he wrote. ‘King John’s struggle with the barons is meaningful only when the relations of the barons to Henry I, Stephen, Henry II, and Richard are also known; and also when the relations between the kings and barons in other countries with feudal institutions are known.’ Similarly, the intelligence services’ dealings with the Cambridge ring of five are best understood when the services’ relations with other spy networks working for Moscow are put alongside them. The significance of Kim Philby, Donald Maclean, Guy Burgess, Anthony Blunt and John Cairncross, and the actions of counter-espionage officers pitted against them, make sense only when they are seen in a continuum with Jack Hayes, Norman Ewer, George Slocombe, Ernest Oldham, Wilfrid Vernon, Percy Glading, Alan Nunn May, William Marshall and John Vassall.

Enemies Within is a set of studies in character: incidentally of individual character, but primarily a study of institutional character. The operative traits of boarding schools, the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, the Intelligence Division, the Foreign Office, MI5, MI6 and Moscow Centre are the book’s subjects. Historians fumble their catches when they study individuals’ motives and individuals’ ideas rather than the institutions in which people work, respond, find motivation and develop their ideas. This book is not a succession of character portraits: it seeks the bonds between individuals; it depicts mutually supportive networks; it explores the cooperative interests that mould thinking; it joins ideas to actions, and connects reactions with counter-reactions; it makes individuals intelligible by placing them in sequence, among the correct types and tendencies, of the milieux in which they thought and acted.

In addition to Evans-Pritchard I have carried in my mind a quotation from F. S. Oliver’s great chronicle of Walpole’s England in which he refers to Titus Oates, the perjurer who caused a cruel and stupid panic in 1678–9 by inventing a Jesuitical conspiracy known as the Popish Plot. ‘Historians’, wrote Oliver in The Endless Adventure,

are too often of a baser sort. Such men write dark melodramas, wherein ancient wrongs cry out for vengeance, and wholesale destruction of institutions or states appears the only way to safety. Productions of this kind require comparatively little labour and thought; they provide the author with high excitement; they may bring him immediate fame, official recognition and substantial profits. Nearly every nation has been cursed at times with what may be called the Titus Oates school of historians. Their dark melodramas are not truth, but as nearly as possible the opposite of truth. Titus Oates the historian, stirring his brew of arrogance, envy and hatred in the witches’ cauldron, is an ugly sight. A great part of the miseries which have afflicted Europe since the beginning of the nineteenth century have been due to frenzies produced in millions of weak or childish minds by deliberate perversions of history. And one of the worst things about Titus Oates is the malevolence he shows in tainting generous ideas.

One aim of this book is to rebut the Titus Oates commentators who have commandeered the history of communist espionage in twentieth-century Britain. I want to show the malevolence that has been used to taint generous ideas.

This is a thematic book. My ruling theme is that it hinders clear thinking if the significance of the Cambridge spies is presented, as they wished to be, in Marxist terms. Their ideological pursuit of class warfare, and their desire for the socialist proletariat to triumph over the capitalist bourgeoisie, is no reason for historians to follow the constricting jargon of their faith. I argue that the Cambridge spies did their greatest harm to Britain not during their clandestine espionage in 1934–51, but in their insidious propaganda victories over British government departments after 1951. The undermining of authority, the rejection of expertise, the suspicion of educational advantages, and the use of the words ‘elite’ and ‘Establishment’ as derogatory epithets transformed the social and political temper of Britain. The long-term results of the Burgess and Maclean defection reached their apotheosis when joined with other forces in the referendum vote for Brexit on 23 June 2016.

The social class of Moscow’s agents inside British government departments was mixed. The contours of the espionage and counter-espionage described in Enemies Within – the recurrent types of event in the half-century after 1920 – do not fit Marxist class analysis. To follow the communist interpretation of these events is to become the dupe of Muscovite manipulation. The myths about the singularity of the Cambridge spies and the class-bound London Establishment’s protection of them is belied by comparison with the New Deal officials who became Soviet spies in Roosevelt’s Washington. Other comparisons are made with the internal dynasties of the KGB and with MI5’s penetration agents within the Communist Party of Great Britain.

The belief in Establishment cover-ups is based on wilful misunderstanding. The primary aim of counter-intelligence is not to arrest spies and put them on public trial, profitable though this may be to newspapers in times of falling sales or national insecurity. The evidence to the Senate Intelligence Committee tendered in 2017 by James Comey, recently dismissed as Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation by President Donald Trump, contains a paragraph that, with the adjustment of a few nouns, summarizes the policy of MI5 during the period of this book:

It is important to understand that FBI counter-intelligence investigations are different than the more commonly known criminal investigative work. The Bureau’s goal in a counter-intelligence investigation is to understand the technical and human methods that hostile foreign powers are using to influence the United States or to steal our secrets. The FBI uses that understanding to disrupt those efforts. Sometimes disruption takes the form of alerting a person who is targeted for recruitment or influence by the foreign power. Sometimes it involves hardening a computer system that is being attacked. Sometimes it involves ‘turning’ the recruited person into a double agent, or publicly calling out the behavior with sanctions or expulsions of embassy-based intelligence officers. On occasion, criminal prosecution is used to disrupt intelligence activities.

For MI5, as for Comey’s FBI, the first priority of counter-espionage was to understand the organization and techniques of their adversaries. The lowest priorities were arrests and trials.

The Marxist indictment of Whitehall’s leadership takes a narrow, obsolete view of power relations. Inclusiveness entails not only the mesh of different classes but the duality of both sexes. In the period covered by this book, and long after, women lacked the status of men at all social levels. They were repulsed from the great departments of state. The interactions in such departments were wholly masculine: the supposed class exclusivity of the Foreign Office (which is a partial caricature, as I show) mattered little, so far as the subject of this book is concerned, compared to gender exclusivity. The key to understanding the successes of Moscow’s penetration agents in government ministries, the failures to detect them swiftly and the counter-espionage mistakes in handling them lies in sex discrimination rather than class discrimination. Masculine loyalties rather than class affinities are the key that unlocks the closed secrets of communist espionage in Britain. The jokes between men – the unifying management of male personnel of all classes by the device of humour – was indispensable to engendering such loyalty. Laughing at the same jokes is one of the tightest forms of conformity.

Enemies Within is a study in trust, abused trust, forfeited trust and mistrust. Stalinist Russia is depicted as a totalitarian state in which there were ruthless efforts to arouse distrust between neighbours and colleagues, to eradicate mutual trust within families and institutions, and to run a power system based on paranoia. ‘Saboteurs’ and ‘wreckers’ were key-words of Stalinism, and Moscow projected its preoccupation with sabotage and wrecking on to the departments of state of its first great adversary, the British Empire. The London government is portrayed as a sophisticated, necessarily flawed but far from contemptible apparatus in which trust among colleagues was cultivated and valued. The assumptions of workplace trust existed at every level: the lowest and highest echelons of the Foreign Office worked from the same openly argued and unrestricted ‘circulating file’; in the Special Branch of the Metropolitan Police, until the 1930s, matters of utmost political delicacy were confided to all men from the rank of superintendent downwards.

At the time of the defection of Burgess and Maclean in 1951, the departments of state were congeries of social relations and hierarchical networks. They were deliberate in their reliance on and development of the bonding of staff and in building bridges between diverse groups. Government ministries were thus edifices of ‘social capital’: a broad phrase denoting the systems of workplace reciprocity and goodwill, the exchanges of information and influence, the informal solidarity, that was a valued part of office life in western democracies until the 1980s. The era of the missing diplomats and the ensuing tall tales of Establishment cover-ups chipped away at this edifice, and weakened it for the wrecking-ball that demolished the social capital of twentieth-century Britain. The downfall of ‘social capital’ was accompanied by the upraising of ‘rational choice theory’.

This theory suggests that untrammelled individuals make prudent, rational decisions bringing the best available satisfaction, and that accordingly they should act in their highest self-interest. The limits of rational choice theory ought to be evident: experience shows that people with low self-esteem make poor decisions; nationalism is a form of pooled self-regard to boost such people; and in the words of Sir George Rendel, sometime ambassador in Sofia and Brussels, ‘Nationalism seldom sees its own economic interest.’ Rational choice is the antithesis of the animating beliefs of the British administrative cadre in the period covered by this book. The theory has legitimated competitive disloyalty among colleagues, degraded personal self-respect, validated ruthless ill-will and diminished probity. The primacy of rational choice has subdued the sense of personal protective responsibility in government, and has gone a long way in eradicating traditional values of institutional neutrality, personal objectivity and self-respect. Not only the Cambridge spies, but the mandarins in departments of state whom they worked to outwit and damage would be astounded by the methods and ethics of Whitehall in the twenty-first century. They would consider contemporary procedures to be as corrupt, self-seeking and inefficient as those under any central African despotism or South American junta.

The influence of Moscow on London is the subject of Enemies Within. As any reader of The Oxford Handbook of the History of Communism will understand, Soviet communism was only one version of a Marxist state. ‘As the twenty-first century advances,’ writes Stephen A. Smith, editor of the Oxford Handbook, ‘it may come to seem that the Chinese revolution was the great revolution of the twentieth century, deeper in its mobilization of society, more ambitious in its projects, more far-reaching in its achievements, and in some ways more enduring than its Soviet counterpart.’ All this must be acknowledged: so, too, that Chinese revolutionaries took their own branded initiatives to change the character of western states. These great themes – as well as reactions to the wars in Korea and Vietnam – however lie outside my remit.

If I had attempted to be comprehensive, Enemies Within would have swollen into an unreadable leviathan. Endnotes at the close of paragraphs supply in order the sources of quotations, but I have not burdened the book with heavy citation of the sources for every idea or judgement. I have concentrated its focus by giving more attention to HUMINT than to SIGINT. There are more details on Leninism and Stalinism than on Marxism. The inter-war conflicts between British and Soviet interests in India, Afghanistan and China get scant notice. There are only slight references to German agents, or to the activities of the Communist Party of Great Britain. There is nothing about Italian pursuit of British secrets. Japan does not impinge on this story, for it did not operate a secret intelligence service in Europe: a Scottish aviator, Lord Sempill, and a former communist MP, Cecil L’Estrange Malone, were two of its few agents of influence. The interference in the 1960s and 1970s of Soviet satellite states in British politics and industrial relations is elided. Although I suspect that Soviet plans in the 1930s for industrial sabotage in the event of an Anglo-Russian war were extensive, the available archives are devoid of material. The Portland spy ring is omitted because, important though it was, its activities in 1952–61 are peripheral to themes of this book. The material necessary for a reliable appraisal of George Blake is not yet available: once the documentation is released, it will need a book of its own. I have drawn parallels between the activities of penetration agents in government departments in London and Washington, and have contrasted the counter-espionage of the two nations. There is a crying need for a historical study – written from an institutional standpoint rather than as biographical case-studies – of Soviet penetration of government departments in the Baltic capitals, of official cadres in the Balkans and most especially of ministries in Berlin, Brussels, Budapest, Madrid, Paris, Prague, Rome and Vienna.

Enemies Within is not a pantechnicon containing all that can be carried from a household clearance: it is a van carrying a few hand-picked artefacts.