Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

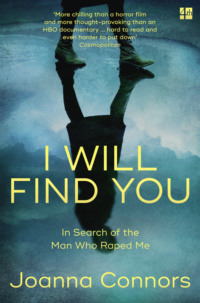

Loe raamatut: «I Will Find You: In Search of the Man Who Raped Me»

I Will Find You

JOANNA CONNORS

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2016

First published in the United States in 2016 by

Atlantic Monthly Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic

Copyright © 2016 by Joanna Connors

Cover photo © Mark Owen / Trevillion Images

Joanna Connors asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Epigraph quote by James Baldwin from “As Much Truth As One Can Bear,” The New York Times (January 14, 1962). Quote on p. 76 from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, translated by Rolfe Humphries (Indiana University Press, 1955), 146–48. Quote on p. 115 by James Baldwin from “Lorraine Hansberry at the Summit,” Freedomways 19:4 (1979) 269–72.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologizes for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

Cover design by Jonathan Pelham

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780007521869

Ebook Edition © April 2016 ISBN: 9780007521876

Version: 2017-02-20

For Dan and Zoe, beloved And for Chris, who went through it with me

Author’s Note

It’s no surprise that the term “Rashomon effect” comes from a movie about a rape and murder. Akira Kurosawa’s masterpiece (based on the work of Ryūnosuke Akutagawa) tells the story of a violent encounter in the woods through the testimony of four characters. Each one recounts a different version of what happened—including the murdered samurai, who testifies through a medium.

“Rashomon effect” has become shorthand for the way perspective can alter memory. Neuroscientific research suggests that memory is not solid. It is capricious and highly susceptible to outside influence, and changes with each retrieval from the brain.

The addition of trauma makes memory the ultimate unreliable narrator of our own past.

I fact-checked my memories in this book with as much evidence as possible, including stacks of documents, dozens of recorded interviews, and my own journals.

But I also relied on my memories. Others who experienced this trauma may, like the woodcutter or the wife in Rashomon, have other perspectives and other stories to tell. To honor their privacy, I have changed the names of some of the people in this book, and changed characteristics that might identify them.

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

—James Baldwin

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Author’s Note

Epigraph

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Acknowledgments

About the Author

About the Publisher

CHAPTER ONE

“Be it remembered”

I was thirty years old when I left my body for the first time.

When it happened, I had not taken any drugs, not for a couple of years. I was sober, it was the middle of the day, I was working, and I did not believe out-of-body reports any more than I believed a man could bend a spoon with his mind.

I worked for a newspaper, where facts mattered and skepticism was essential, and I tried to develop the cynicism I saw in older reporters while praying no one would figure out I was a fraud who had no business being in a newsroom.

I had just moved to Cleveland from Minneapolis to start work at The Plain Dealer, the city’s daily paper, and, as it proclaimed in the front-page banner, “Ohio’s Largest Newspaper.” It was my second job in what amounted to the family trade. My grandfather had worked at The Knickerbocker News in Albany, New York, my father was a reporter and editor at the Miami Herald when I was a girl, and I had worked at the Minneapolis Star (now the Star Tribune) before going to Cleveland.

I had resisted following in my father’s wake until I was nineteen. I didn’t want his career. By then, he was a magazine editor, and I was determined to separate myself from everything about my parents and their suburban lives. On visits home, I used the term “bourgeois” a lot. I was very young.

The only reason I walked into my college newspaper to ask for a job was because my sister Nancy worked there and told me they paid ten cents a column inch. I found my career and met my husband in that little basement newsroom, where I discovered that newspaper work takes you places you’d never get to go otherwise, and introduces you to people you would never come near without a press pass. Even better, newspaper people know how to have fun. I learned that early in life, when I was seven years old and my parents had a Miami Herald party in our backyard. I stayed up late with my sister, peeking through the window, watching them drink and laugh and flirt and, when it got very late, jump into the pool naked. My parents didn’t get naked, which would be too disturbing to recall, but the party did end dramatically, with my mother stepping on a broken glass and having to go to the hospital for stitches in her foot. I remember one of the men saying, “I’ll just pour some gin on it, Susie,” and my mother shouting, “No!” and everybody laughing. This frightened and thrilled me in equal measure.

Going to work in a newsroom used to be like going to a cocktail party every day, with all your clothes on and without the booze or the blood. Usually. Every newspaper has its feuds, gossip, and vanity; most have a legend or two of a newsroom brawl. At The Plain Dealer, people swore that a reporter once threw a typewriter—a heavy electric one—at an editor and then left the building, never to return. Everyone remembered the fight; no one remembered the reason for it.

Cynicism is both a badge of honor and a professional liability. Newspaper people don’t start out that way; almost everyone I know started out as an idealist wanting to bring justice to an unjust world. Cynicism seeps in over time, a slow acidic leak that erodes the idealism, the natural result of being told lies all day long, of calls not returned and records withheld, of corners cut to get a story in on time.

So I did not believe that out-of-body experiences were real. And yet: At 4:30 p.m. on a hot July afternoon, on a college campus in Cleveland, Ohio, I slipped away from my body and rose, up and up, until I was hovering somewhere in the air.

I looked down at the stage of a small theater, where I was on my knees in front of a man who held a long, rusty blade to my neck and was ordering me to suck on his penis.

“Suck on it,” he said, pushing on my head.

From my perch above this scene, I watched with a calm I’d never felt before.

It had come in an instant, this leaving my body. It happened as soon as I saw my own blood on my hand. The blood stunned me. I had not felt a cut, just the cool metal at my throat, as the man dragged me across the stage, but I didn’t know he had used it until a few minutes later, when I put my hand to my neck. It felt sticky.

I looked at my hand, and saw a smear of red.

Dread struck at once, slithering through my chest and into my stomach. I felt its venom spread outward, through my limbs, and then up into my throat. The poison worked in quick stages: shock, then panic, then paralysis.

By the time my brain began to work again, I was looking at myself from high above, up in the theater’s fly space among the ropes and lights. From that vantage point, I watched the man rape me.

I observed with an odd detachment. It was as though what was happening on that stage was happening to someone else. I was viewing a Hollywood thriller, and we had come to the inevitable rape scene. They were actors; I was the audience.

The woman on the stage looked up at the man. She moved in slow motion.

“Suck on it,” he said again. “I got to get off.”

I wondered when he would kill the woman. Not whether he would do it, but when. I knew it would happen, the way you know certain secondary characters will be killed in a movie. From my position above, I accepted it as a necessary plot element.

I was not sad, or scared, hovering up there. If anything, I was curious. How would he do it? What would I feel?

I understood that the girl on her knees was alone, but soon she would not be. She would join all the other girls who had been raped and then killed. I wondered if this was how they felt when it happened to them. Detached. Alone. Floating out of time.

All those dead, lovely girls. I still think of them, all the time.

We printed their high-school graduation pictures in our newspaper, their faces turned and tilted by the photographer so that they seemed to be gazing toward a future they had just started to imagine, their long hair so shiny you could practically smell the Herbal Essences shampoo when you looked at them.

Our editors sent reporters and photographers to the woods and roadside ditches where sheriff’s deputies were digging, where the girls had lain, ever patient, waiting to be found. The reporters interviewed their keening mothers while the silent fathers, stunned by loss and fury, tried to comfort them. The reporters took their graduation pictures back to the newsroom, and when the time came they covered the trials of the men who killed them. If the time came.

And then, a week or a month later, we forgot them. We went on to the next one. There was always a next one.

I pictured all the girls together, somewhere. Maybe they were watching this happen, just as I was, and waiting for me.

I guess you could call this the story of a quest. When it all started, though, I didn’t think of it as one. The great quest stories all revolved around men—men going off into unknown lands on brave adventures. Kings and gods sent them off on their journeys, sometimes giving them magic swords. Poets sang of them, telling stories of heroes who sailed ships on wine-dark seas, rode over mountains on the backs of elephants, searched for holy treasure, rescued beautiful women.

I was a middle-aged, middle-class working mother, living in the suburbs of Cleveland, Ohio, a woman who once thought of herself as fearless but now was afraid of just about everything.

I did not undertake journeys. When I had a choice, I rarely left my house.

This was not how I always was. There was a time when I hitchhiked everywhere, when everyone I knew did, too, feeling a reckless thrill whenever a car pulled over and the passenger door opened and we ran to it, not knowing who would be sitting in the driver’s seat. I walked alone in the dark, everywhere, breaking the rule girls learn early in life from the Grimm Brothers: Never venture into the dark forest alone. At sixteen, I decided that rule did not apply to me. If a man could do it, then I should be able to do it, too.

What happened to that headstrong girl? Whenever I thought about her, I felt a wave of melancholy. I missed her.

Now I was afraid of sitting in a movie theater. Since I was by that time the film critic for my paper, this made my job complicated. When I went to a screening alone, which happened fairly often in a one-newspaper town, I sat with all my muscles clenched, struggling to focus on the movie. I finally asked the theater managers to lock the doors on me, which they did, though it must have broken fire department regulations. With this and countless other silly but imperative solutions, I organized my life to avoid risk.

I also became practiced at avoiding everything to do with the rape. After it was all over, after I had told the police and the doctors and the prosecutor and judge and jury, after they’d sent the rapist to prison for a long time, I stopped talking about it. I took what had happened and buried it inside myself, as deep as I could. I didn’t tell my friends. I didn’t tell my two children when they were old enough to hear it. I didn’t talk about it anymore with my husband or sisters or mother. I told them, and myself, that I was fine. Fine! Just fine.

But here’s the thing I discovered: I might have buried this story, but it was not dead. I had buried it alive, and it grew in that deep place I put it, like a vine from some mutant seed, all twisted and ugly and tenacious as kudzu. As it grew, it strangled a lot of other stuff in me that should have been growing. It killed my courage and joy. It killed my trust in the world.

Worse, the vine reached out to entangle my children. When I was raped, I was married but I did not have children yet. My son was born a year and a half after the rape, my daughter a couple of years after that. But even though they were not alive when it happened, research shows that they inherited my rape and the terror that came with it. They lived in its twisted grip with me.

I was always waiting for something terrible to happen to them. I imagined those terrible things in documentary detail. Car accidents. Kidnappers. Pedophiles. Murderers. They filled my brain like the inventory in a torture chamber. When Eric Clapton’s “Tears in Heaven” came out and I read the backstory—he wrote it for his four-year-old son, who fell to his death from an apartment window—the song became the inner sound track to my days. I imagined these things and rehearsed my grief, which always ended the same way: I would not be able to go on.

I would not write a beautiful song about them. I would not make art or sense out of their death. I would jump out of the window right after them.

I knew all parents worry about safety. The minute they are born, our children make us all hostages to fortune. But these parents considered the dangers in the world and figured out ways to avoid them. They baby-proofed their kitchens and medicine cabinets; they kept their eye on their children when they played outside and made sure they wore helmets when they learned to ride a bicycle.

I was not one of those reasonable parents. I baby-proofed our entire lives, putting locks on everything, including the children themselves.

I hovered and fretted over them nonstop, zooming to red alert if I heard a random shriek when they played in the backyard. When they went for a sleepover at a friend’s house, I stayed awake all night, waiting for the emergency call from the hospital.

When I returned to work six months after my son was born, we hired a babysitter, an affectionate middle-aged woman with a musical voice and a lap like a pillow. She made our baby son giggle when she arrived each morning.

I had checked her references, but, based on nothing, I felt uneasy about her. At work, I worried about what she might do to my son. This was before nanny cams, but if they had existed I would have mounted one in every corner of the house.

I asked my husband, who was then a police reporter at the paper, to do a criminal-records check on her. In most states it’s easy to access these public records now, online, but in 1985 it involved an in-person visit to the Clerk of Courts.

When he turned up nothing, I was not reassured. One night I followed her home and parked on the street, watching her apartment windows like a cop on a stakeout. Then I went to see her boss at the nearby mall, where she worked every Saturday and Sunday night, cleaning after the stores closed. He refused to tell me anything about her, even when I started crying. I left, hating him, and the next day I let her go. I couldn’t get over my fear that she would hurt my son.

I started working at home, where I could keep an eye on the new babysitter we hired. A friend had recommended her. I began to nurture suspicions about her, too.

My dark thoughts spread. For a time, I even imagined my husband might be abusing our son. I had no evidence of this, none at all. My husband loved our son more than he loved me, but it didn’t matter that I had no reason to suspect him. I hated leaving him alone with my baby. Once I left to do errands and returned ten minutes later, much sooner than I’d said I would, thinking I would catch him in the act. They were outside, sitting on the grass, examining an earthworm.

I was aware that this was not normal. I suspected that I was close to being delusional. Even so, I could not turn it off. I couldn’t tell anyone about these fears, either. I knew it would make me look crazy—I was sane enough to see that, at least.

So I turned my life into performance art. I acted normal, or as normal as I could manage, all the while living on my secret island of fear. As time went on, the list of my fears continued to grow. I was afraid of flying. Afraid of driving. Afraid of riding in a car while someone else drove. Afraid of driving over bridges. Afraid of elevators. Afraid of enclosed spaces. Afraid of the dark. Afraid of going into crowds. Afraid of being alone. Afraid, most of all, to let my children out of my sight.

From the outside, my performance worked. I looked and acted like most other mothers. Only I knew that my entire body vibrated with dread, poised to flee when necessary.

I suppose it’s lucky I realized I was on a quest only when it was almost over.

It began on another college campus, twenty-one years after my rape. It was 2005, a time when the world seemed to be collapsing. That summer, terrorists had attacked three trains and a bus in London, murdering fifty-two people and injuring seven hundred. A series of terrorist bombs in Bali killed twenty-six people. In the United States, Hurricane Katrina hit in August, leading to the deaths of almost two thousand people in the aftermath of flooding and violence, and destroying much of New Orleans, the Gulf Coast, and Americans’ sense of trust in the fairness of our government. I was feeling, along with the rest of the country, a new form of anxiety about the future. It felt like we were all standing on a precipice.

That fall, my son left for his second year of college and my daughter started her last year of high school.

The schools had been prepping the kids since third grade for college admissions, and when October came, it was time for her Big College Tour—a ritual that puts teenagers and their parents in a car together for several days, where they bond over the shared conviction that it really is time for the teenager to go away from home for a while.

We were on Day Two, at college number three or four. Zoë was in that senior-year stage where half the time she was so impatient and annoyed with me that I couldn’t wait for her to leave and take her sighs and silences with her, and half the time she was the sweet, funny little girl who used to squiggle down under the covers with me at night, or play Dolphin in the Pool. In those games, I was her trainer, feeding her pretend fish for each somersault she did below the surface, her little body slipping like mercury through the water.

Sweet Zoë was on this trip, keeping me laughing and choosing all the CDs as we drove, a heavy rotation of Modest Mouse’s CD, Good News for People Who Love Bad News. Appropriate. Zoë’s good mood might have had something to do with the three days she was taking off from school. Still, I was surprised that she was walking with me on the campus tours rather than ten yards behind me, the way my son had on his tours. Dan had hung back with the other kids who were concentrating on the sidewalks, pretending they did not know those dorks ahead of them in the unfortunate mom jeans—who, I want to point out, included many of the dads. It didn’t help when I knocked over an entire row of bicycles, domino style, at one of the recreation centers.

“Sorry!” I kept saying as I tried to put twenty-five bikes back on their stands. “Sorry!”

When I looked around, Dan had vanished. I didn’t blame him.

But Zoë was with me all the way. She was making me miss her before she even packed the first of the sixty-three boxes of stuff she took with her the next year. All of this made me feel unexpectedly buoyant. I had loved everything about college, especially the going-away-from-home part. I even skipped my senior year in high school to get there a year early. The University of Minnesota was where I found myself and my tribe, that day I walked into the subterranean offices of the Minnesota Daily, the college paper, and asked for a job. Half the staff was in the darkroom, smoking a joint. The rest of them were sitting around talking about Hunter S. Thompson. Everyone wanted to do his gonzo journalism that year, or imitate Tom Wolfe’s new journalism, and since the students controlled the paper, a lot of them did. It made for unusual coverage of the Board of Regents meetings.

The rain started just as Zoë and I pulled into the visitors’ lot at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, a college best known for its psychology program, which she had decided was where she wanted her life to go. When Sigmund Freud made his first and only trip to America, in 1909, he went to Clark to deliver his famous lectures. A life-size bronze statue of Freud, deep in thought, sits on a bench on the campus.

Inside the admissions office, a cluster of parents at the windows murmured about whether to do the tour in the rain or skip it. Zoë wanted to see the campus, so when the tour guide called out that it was time to start, we buttoned up our jackets, opened our one umbrella, and fell in with the swarm of parents and seniors.

Our guide, a skinny boy with fogged-up glasses, walked backward and ignored the rain, which had started as a drizzle but now came down steady and cold. We stopped to see the same things we’d seen at the last campus: a dorm and a dorm room, the cafeteria, the gym. By this point, the tour had sustained several dropouts.

“Now we’ll head over to the library,” the guide said.

At the back of the crowd, Zoë and I held the umbrella between us, the rain dribbling down her right side and my left. We lurched along, like mismatched partners in a three-legged race.

“Listen, I’m prepared to take it on absolute faith that every university does, in fact, have a library,” I said. “I don’t need to see to believe.”

Zoë smiled, but she also sighed. I recognized that sigh as my own when I was seventeen, a sign that the mother-daughter bonding was coming unglued.

I was about to suggest cutting away from the group and going for coffee when the guide stopped on the path. Freud sat nearby, awaiting what had been building up inside me for two decades to emerge. He knew more than I did.

The guide gestured to a glowing light and said, “You’ve probably noticed these blue lights around campus. They’re safety stations. If you’re walking alone at night and you think someone is following you, or you might be in danger, you get to one of these blue lights, call, and help will be there within five minutes.”

All the parents nodded, reassured.

Those parents were idiots.

“Five minutes?” I whispered to Zoë. “Who are they kidding? Five minutes is too late. Way too late. You could be dead in five minutes.”

Zoë, who remembers it now as a stage whisper that everyone heard, looked at me for a long pause, shook her head, and went on with the group, leaving me standing alone beneath the blue light.

I watched her walk away, the hem of her jeans dragging on the wet pavement. I felt the same way I always feel when I look at her: amazed that this girl, so unlike me, is my daughter. Zoë was like the girls I envied at that age, the girls who blazed through the halls of my high school, while I thought only about cutting class and going anywhere else. She was strong, confident, smart, beautiful. She was funny. She was not afraid to speak her mind and ask for what she wanted.

I looked at my daughter and saw a young woman who was ready to go out into the world and make it her own. But now I saw something else, too.

She was prey.

I was sending her to a campus. I could see her standing in a pool of blue light on a dark path, scared, alone, calling for help, watching a man walk toward her while she waited for someone to come save her.

She had five minutes.

The venomous snake returned, slithering through my body. Panic dropped from my chest to my gut so fast I thought I might throw up. My vision blurred and narrowed, dark at the edges. The ordinary campus sounds around me turned into a muffled roar in my ears. I dropped the umbrella and grabbed the post with the blue light with both hands, willing myself to keep standing.

Then I felt myself float up into the air like a balloon escaping from a child’s fist. I saw the middle-aged woman below, rain dripping off her hair into her face.

I was back at that other campus, twenty-one years before, suspended high above a stage and looking down at myself.

Tasuta katkend on lõppenud.