Loe raamatut: «Black Enough»

First published in the United States of America by Balzer + Bray in 2019

Balzer + Bray is an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

Published simultaneously in the UK by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2019

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is

Black Enough: Stories of Being Young and Black in America

Copyright © 2019 by Ibi Zoboi

“Half a Moon” copyright © 2019 by Renée Watson

“Black Enough” copyright © 2019 by Varian Johnson

“Warning: Color May Fade” copyright © 2019 by Leah Henderson

“Black. Nerd. Problems.” copyright © 2019 by Lamar Giles

“Out of the Silence” copyright © 2019 by Kekla Magoon

“The Ingredients” copyright © 2019 by Jason Reynolds

“Oreo” copyright © 2019 by Brandy Colbert

“Samson and the Delilahs” copyright © 2019 by Tochi Onyebuchi

“Stop Playing” copyright © 2019 by Liara Tamani

“Wild Horses, Wild Hearts” copyright © 2019 by Jay Coles

“Whoa!” copyright © 2019 by Rita Williams-Garcia

“Gravity” copyright © 2019 by Tracey Baptiste

“The Trouble with Drowning” copyright © 2019 by Dhonielle Clayton

“Kissing Sarah Smart” copyright © 2019 by Justina Ireland

“Hackathon Summers” copyright © 2019 by Coe Booth

“Into the Starlight” copyright © 2019 by Nic Stone

“The (R)Evolution of Nigeria Jones” copyright © 2019 by Ibi Zoboi

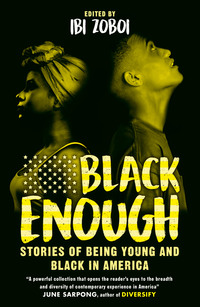

Cover image of girl copyright © Masterfile; cover image of boy copyright © Shutterstock

Cover design copyright © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

The authors assert their moral right to be identified as the authors of their work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008326555

Ebook Edition © 2019 ISBN: 9780008326548

Version: 2018-12-18

TO VIRGINIA HAMILTON AND WALTER DEAN MYERS.

WE STAND ON THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS.

Contents

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

INTRODUCTION

JUNE SARPONG

INTRODUCTION

IBI ZOBOI

HALF A MOON

RENÉE WATSON

BLACK ENOUGH

VARIAN JOHNSON

WARNING: COLOR MAY FADE

LEAH HENDERSON

BLACK. NERD. PROBLEMS.

LAMAR GILES

OUT OF THE SILENCE

KEKLA MAGOON

THE INGREDIENTS

JASON REYNOLDS

OREO

BRANDY COLBERT

SAMSON AND THE DELILAHS

TOCHI ONYEBUCHI

STOP PLAYING

LIARA TAMANI

WILD HORSES, WILD HEARTS

JAY COLES

WHOA!

RITA WILLIAMS-GARCIA

GRAVITY

TRACEY BAPTISTE

THE TROUBLE WITH DROWNING

DHONIELLE CLAYTON

KISSING SARAH SMART

JUSTINA IRELAND

HACKATHON SUMMERS

COE BOOTH

INTO THE STARLIGHT

NIC STONE

THE (R)EVOLUTION OF NIGERIA JONES

IBI ZOBOI

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHIES

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

INTRODUCTION

JUNE SARPONG

Any child of colour raised in the West will have been told early on by their parents or guardians that “they need to work twice as hard” in order to achieve success. Those people may not recall exactly when they had their first “conversation”, but they will remember having it.

For non-white children growing up as minorities in Europe or North America, the first uncomfortable “conversation” with their parents isn’t about the birds and the bees – that comes later – it’s about more pressing matters that will impact them from the moment they leave the safety of their parents’ home and enter the world.

Pre-school can often be a baptism of fire for children of colour. While white children may have the luxury of waiting till their tweens before having to learn about the realities of life, children of colour are told much earlier, their “conversation” being more about the inequalities and discrimination that they will invariably face at some point in their lives. Unfortunately, this is regardless of how privileged, talented or brilliant they might be. This is a heartbreaking burden that parents of colour bear, or white parents of non-white children must face. Children of mixed-race heritage are one of the fastest-growing ethnic groups in Britain, so now many parents who themselves might not have had a personal experience of discrimination are having to have that “conversation” with their children.

In Black Enough, Ibi Zoboi powerfully weaves together a collection of short stories that examine what it means to be young and black in America. These stories bring us up close and personal with heroes and heroines who are trying their best to win on an unlevel playing field: young people refusing to give up even when the odds are stacked against them; young people who will open your hearts and minds in ways you couldn’t imagine.

Like all great coming-of-age adventures, you, the reader, will leave as much changed as the protagonists. Black Enough will open your eyes to US injustices that are just as relevant here in the UK; Black Enough will provide you with a new-found appreciation for the resilience of the human spirit; and, more importantly, Black Enough will remind you of our shared humanity.

Whether you are a young person dealing with similar challenges faced in the pages of this book, a parent wanting to raise “woke” children, or simply an ally for change and inclusion, Black Enough will arm you with extra tools on your journey to make the world a fairer place.

INTRODUCTION

IBI ZOBOI

I was born in a country known for having had the first successful slave revolt in the world. Way back in 1804, Haiti became the very first independent Black nation in the Western Hemisphere. If global Blackness had a rating scale of one to ten, the Haitian Revolution has got to be at level ten, being the most Blackest thing that ever happened in history.

But none of that mattered when I first immigrated to the United States as a child. The Black and Latinx kids in my Brooklyn neighborhood didn’t know and didn’t care that my native country had once been a hub for freed slaves from America. According to them, I wasn’t Black enough. I wore ribbons in my hair and fancy dresses to school, and I had a weird accent and a funny name. Most important, I didn’t know how to jump double Dutch or separate a sunflower seed from its shell with just my front teeth, and I was off-key and off-beat when stomping, clapping, and singing to the latest cheers. These were all definitions of Brooklyn’s summertime Black girlhood.

By the time I started high school, I had mastered all of those things and could easily blend into New York’s particular brand of teen Blackness, even while tucking away the quirky parts of myself—my love of sci-fi, disco music, and John Stamos.

In college, my small Black world expanded when I met my first roommate, who had the thickest Southern accent I had ever heard. My best friend in high school was African American and I’d been to her big family cookouts and even to visit her cousins in a small Black town in South Carolina. I’d been a little jealous that she had such a big family and at a moment’s notice could be surrounded by a plethora of aunts, uncles, and cousins. This was my first glimpse into African American culture—one with deep roots in the South. But that new roommate of mine with the Southern accent was from Rochester, New York, and her family had lived there for as long as she could remember.

Once I met new friends from Nigeria, Ghana, South Africa, and even England, my idea of Blackness began to expand. It was only then that I started to connect my own Brooklyn Blackness to a global idea of Blackness. After all, while the girls in my neighborhood teased me about not knowing how to spit out sunflower seeds, they didn’t know how to properly eat a mango, or know Creole or Patois or any of the Caribbean ring games. But before long, I knew there was a fine thread that connected all of these cultural traditions to each other.

Blackness is indeed a social construct. Within the context of American racial politics, there can be no Black without white. No racism without race. But the prevalence of culture is undeniable.

What are the cultural threads that connect Black people all over the world to Africa? How have we tried to maintain certain traditions as part of our identity? And as teenagers, do we even care? These are the questions I had in mind when inviting sixteen other Black authors to write about teens examining, rebelling against, embracing, or simply existing within their own idea of Blackness.

Renée Watson’s opening story, “Half a Moon,” places Black teen girls outdoors, among trees, and swimming in lakes—and yes, there is the common understanding that the hair situation is already handled. Jason Reynolds and Lamar Giles fully capture #blackboyjoy in their respective stories “The Ingredients” and “Black. Nerd. Problems.” There are no pervasive threats to their goofing around and being carefree. The intersectional lives of teens who are grappling with both racial and sexual identity are rendered with great care and empathy in Justina Ireland’s “Kissing Sarah Smart,” Kekla Magoon’s “Out of the Silence,” and Jay Cole’s “Wild Horses, Wild Hearts.” From Leah Henderson’s story of appropriation at a boarding school to Liara Tamani’s story of inappropriate nude pic games at a church beach retreat, the teens in Black Enough are living out their lives much like their white counterparts. They are whole, complete, and nuanced.

Like my revolutionary ancestors who wanted Haiti to be a safe space for Africans all over the globe, my hope is that Black Enough will encourage all Black teens to be their free, uninhibited selves without the constraints of being Black, too Black, or not Black enough. They will simply be enough just as they are.

HALF A MOON

RENÉE WATSON

DAY ONE: SUNDAY

Dad left when I was seven years old.

Mom thinks I was too young to remember Dad living with us, that I am holding on to moments I heard about but don’t really know for myself. But I am seventeen years old now and I know what I know. Mom is much further from seven, so maybe she doesn’t understand that at seventeen years old a person can still remember being seven, because it wasn’t that long ago.

Seven was watching Saturday-morning cartoons and practicing counting by twos, fives, tens. I remember. Seven was fishing trips with Dad and Grandpa, and being crowned honorary fisherwoman because once I caught more than they did. Seven was family camping trips and looking up at the night sky with Dad, pointing to the stars that looked like polka dots decorating the sky. Mom mostly stayed in the RV, and one time—the time when a snake crawled into Mom’s bag—she made Dad end the trip early and we checked into a hotel.

Seven was Dad and Mom arguing more than laughing. Seven was staying at Grandma’s on weekends “so your parents can have some time together,” Grandma would say. At Grandma’s house there was no arguing or slamming doors. Only puzzle pieces spread across the dining room table, homemade everything, and Grandma’s gospel music filling the house.

Seven was Dad leaving Mom. Leaving me.

And now, seventeen is spending my spring break working at Oak Creek Campgrounds as a teen counselor for sixth-grade students, because I have to work, have to help out at home, because Mom can’t take care of the bills alone.

Seventeen is knowing what to pack for trips like this because I’ve done this before at fourteen, fifteen, and sixteen: allergy pills, bug spray, raincoat, Keens for the walking trails, and my silk scarf so that I can tie my hair up at night. I braided my hair before I left so that if it rains, my hair won’t stand on top of my head, making me look like I got electrocuted.

When I was in middle school, I was a camper at the Brown Girls Hike summit. That’s one of the requirements for becoming a counselor. The annual camp is for Black girls living in the Portland metro area. Mrs. Thompson started the camp because she felt Black teens in Portland needed to learn about and appreciate the nature all around us. Every year she tells us, “Our people worked in the fields, we come from farmers and folks who knew how to get what they needed from the earth. We’ve got to get back to some basics. We’ve got to reclaim our spaces.”

This is my last year working for the camp before leaving for college, so I want to make it the best one ever. But as soon as the bus full of sixth-grade girls pulls into the parking lot, I start having doubts that any good will come of this week. Out of all the girls on the bus, there’s one I recognize. She is sitting at the front, all by herself. She is a big girl with enough hair to give some away and still have plenty. As soon as I see her, my heart vibrates and my mind replays ages seven and eight and nine and ten, and eleven and twelve and all the years without my dad, because the girl on the bus sitting on a seat by herself is my dad’s daughter.

Brooke.

She was born when I was seven.

She is the reason Dad left Mom. Left me.

I’ve seen her before, always like this, as I am going about my regular life. She shows up in places I don’t expect. Once at Safeway when I was with Mom grocery shopping because there was a sale on milk. She was coming down the aisle with Dad, the two of them with a cart full of things that weren’t on sale, no coupon ads in hand. We said hello, but that was it.

Another time I saw her at Jefferson’s homecoming football game. The whole community was out, and my aunt kept joking about how you can’t be Black in Portland and not know every other Black person somehow, someway. “It’s like a family reunion,” she said.

Except Brooke is not my family.

She is the girl who broke my family.

During the game, I couldn’t stop staring at Brooke, thinking how much she looks like Dad and wondering how it is that I came out looking just like Mom—tall and thin—more straight road and flat terrain than curves and mountains. I could tell we were opposite in personality, too. She couldn’t keep still all night, full of laughter and words, waving to friends, singing along with the music at halftime. So much energy she had. Such joy spread across her face.

Not like today.

Today, she is not with her mom or my dad. Today, when she gets off the bus she is walking alone and her head is hung low and she looks completely out of her comfort zone. Maybe she is only joyful when she’s with her family. Maybe she wasn’t prepared to be on a camping trip with girls from North Portland. She lives in Lake Oswego. I doubt she’s ever been around this many Black girls at once. I step back a bit, hide behind Natasha, the only other teen counselor I like in real life, outside of camp. We’ve worked together every year. Natasha’s family is the kind you see in the frames at stores, the kind on greeting cards, so I don’t tell her my father’s daughter is on that bus. Natasha doesn’t know anything about dads leaving their children.

Mrs. Thompson, the only person I know who can make a T-shirt and jeans look classy, stands at the bus waiting for the door to open. Usually as campers get off the bus, we clap and cheer and usher them into the main lodge for the welcome and cabin assignments. But I keep hiding behind Natasha, who turns and asks, “You all right?” as she claps and yells, “Welcome, welcome.”

Brooke doesn’t notice me. She is occupied with pulling her designer suitcase with one hand and holding her sleeping bag with the other. She looks like she is prepared to go to a fancy resort, not a muddy campground. I think about all the money Dad must spend on her name-brand clothes and shoes, her hair and manicures. This camp. She is probably one of the few girls here who paid full tuition.

Once we are all in the main hall, Mrs. Thompson gives a welcome, reviews the rules, and then tells us what our room assignments will be. Each teen counselor is responsible for four campers. She explains, “You will all have a teen counselor, or what I like to call a big sister, to look up to while you are here. If you need anything, please reach out to her.”

I see Mrs. Thompson pick up her folder. She reads the master roster and begins to call out the cabin assignments. All the groups are named after a color. After she calls the Red, Yellow, and Gray groups, she says, “Raven, come on down!” like she’s on The Price Is Right.

I walk to the front and stand next to Mrs. Thompson. Brooke is sitting right in the first row. She finally sees me. At first there is shock on her face but then her expression softens and she smiles and waves.

I look away.

Mrs. Thompson says, “Raven is responsible for the Green Campers. If you have a green folder, please come forward. That’s Mercy, Cat, Hannah, and Robin. You will be in Cabin Three with Natasha and the Blue Campers.”

The girls rush over to me, green folders in hand and smiling those shy first-day-of-camp smiles. I don’t look at Brooke when the girls crowd around me, giving me hugs like they already know me.

DAY TWO: MONDAY

It looks like it snowed last night. The black cottonwood trees are fragrant and sweet smelling and the wind has blown their fluff across the campgrounds. The snow-like flowers stand out bright against the darkness of the fallen brown branches. I am sitting on the porch in a rocking chair across from Mercy, Cat, and Hannah, who are sitting on the steps.

We are waiting for Robin to come down so we can head over to the dining hall for breakfast. Natasha’s group got to the showers first, so my girls had to wait. Natasha and I were smart enough to take our showers last night, because we know how these things go.

“I’ll see you all over there,” Natasha says to me as she leads the Blue Campers out the door, Brooke dragging behind them like the caboose of a train. I was relieved that she wasn’t in my group, but having her this close to me, in the same cabin, is just as awkward.

We still haven’t spoken to each other. What is there to say?

I watch Brooke as she walks to the dining hall and wonder what she is thinking, wonder what she knows about me, my mom. The other Blue Campers are walking side by side up the pathway, close to Natasha, who is leading the way up the steep hill. I watch Brooke trying to keep up, her plump legs climbing as fast as they can. I don’t think Natasha or the other girls realize how far behind she is.

The food at Oak Creek is some of the best eating I’ve ever had. The head cook is from New Orleans, and everything about her meals reminds us of where she is from. The dining hall is a symphony of mouths chewing, mouths talking, mouths laughing, mouths yelling across the room. Mrs. Thompson makes an announcement that it is the last call for the kitchen and if anyone wants more, they should go up now.

The symphony continues. More mouths chewing, mouths talking, mouths laughing, mouths yelling across the room. And then Mercy’s voice cuts through all the noise, like a siren. “You’re too fat to be getting seconds!”

I turn to see who Mercy is yelling at, getting ready to give my lecture about kindness and respect, because I am seventeen and that is what I am supposed to do, be an example. When I turn around, I see Brooke standing there with her tray, head down.

“Yeah,” one of the Blue Campers says, “you think just because you got long hair and expensive things you’re all that. But you’re not. You could barely walk up the hill this morning. You need to go on a diet.”

I don’t know what Brooke’s hair and belongings have to do with her weight. Sometimes, it’s easier to be mean to a person than to admit that you wish you were that person.

All the girls except Robin laugh. I think maybe I should say something since I am a fake big sister to Mercy and a real big (half) sister to Brooke. If Mrs. Thompson was standing here, she’d be disappointed and tell me that she expects more from me. If Mom was standing here, she’d be disappointed and tell me it’s not Brooke’s fault my dad left. She’d tell me I can’t go giving Brooke these feelings that really belong to Dad. But neither of them is standing here, so I don’t have to do what I know they’d want me to do. Besides, before I can even open my mouth, Natasha is already handling it. “It’s none of your business what she eats,” Natasha says. She puts her arm around Brooke, like a big sister would.

I find the words I know I should say and reprimand Mercy and the girl from the Blue group, but something in their eyes tells me they don’t believe I am as upset as I am pretending to be. Once I threaten to tell Mrs. Thompson, they agree to apologize. Brooke doesn’t even acknowledge them when they say, “Sorry.” She just keeps her eyes straight ahead, not looking at me either.

The Green Campers and the Blue Campers walk over to the cabin where workshops are held. Robin walks close enough to Mercy and her clique to be one of them but also close enough to Brooke to say, I see you, I know. I notice Brooke struggling again to get up the hill. She is breathing hard and sweating.

I could walk slower, let the others go ahead and stay behind with Brooke, but instead, I walk with my Green Campers. They are my responsibility; they are the reason I am here.

Natasha and I are outside on the back porch waiting for the botany class to end. The black cottonwood trees are still shedding. It looks like someone made a wish and blew a million dandelions into the sky. I am imagining a million of my wishes coming true, wondering what it would be like to want nothing, when I hear the botany teacher say, “Black cottonwoods are also known as healing trees, as they are good for healing all types of pains and inflammations. Some say this tree possesses the balm of Gilead because of the nutrients that hide in the buds and bark. Throughout centuries people have made salves from the tree to heal all kinds of ailments.”

When I hear this, I think of Grandma’s gospel records and how she is always humming along with Mahalia Jackson:

There is a balm in Gilead,

there is a balm in Gilead.

The botany teacher says, “There was a time when there was no hospital to go to and people knew how to rely on the earth to supply what they needed, how to mend themselves.”

There is a balm in Gilead

to make the wounded whole.

Natasha says, “You listening to me?”

I say yes, even though I am not because she is just talking about her boyfriend again, asking (but not really asking) if she should break up with him.

There is a balm in Gilead

to save a sin-sick soul.