Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

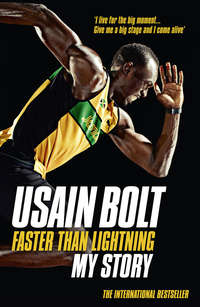

Loe raamatut: «Faster than Lightning: My Autobiography»

Title Page

1 I Was Put on This Earth to Run

2 Walk Like a Champion

3 My Own Worst Enemy

4 Where Mere Mortals Quiver, the Superstar Becomes Excited by The Big Moment

5 Living Fast

6 The Heart of a Champion, a Mind of Granite

7 Discovering the Moment of No Return

8 Pain or Glory

9 Go Time

10 Now Get Yours

11 The Economy of Victory

12 The Message

13 A Flash of Doubt, a Lifetime of Regret

14 This is My Time

15 I Am Legend

16 Rocket to Russia … and Beyond

Appendix

Acknowledgements

Picture Section

Copyright

About the Publisher

Highway 2000, Vineyard Toll, Jamaica, 29 April 2009

Man, I gripped that steering wheel hard as the BMW M3 Coupe flipped once, twice, three times; the roof of the car bounced off the wet road and into the ditch. My windscreen smashed, an airbag popped. Bang! The bonnet crumpled as it hit the ground with a crunch.

Everything was still as I came around to what had happened. There was a weird quiet, like the tense, anxious seconds that always took place on a start line before any major championship race. Sssshhhhh! The silence was broken only by the hammering rain outside and the tick-tick-ticking of an indicator light. It was probably the only thing still working. My car was twisted up in a ditch and smoke was pouring out of the engine.

Stress can do crazy-assed things to the mind. I knew something wasn’t right, but it took a second or two for me to realise that I was upside down and my seat belt was the only thing holding me in place. It was such a weird sensation, checking for injuries above my head, in my legs, my feet. Thankfully, I couldn’t feel any pain as I stretched and gently tested the muscles from my toes down.

‘Yo, I’m all right,’ I thought. ‘Me all right …’

In a split second, the accident flashed through my mind and, oh God, it was bad. I’d been driving through the countryside with two girls, friends of mine from Kingston. Manchester United were playing a Champions League semi-final later that day and I was so desperate to catch the game on TV that as we hit the bumpy, country roads near Trelawny, my home parish in the north-west corner of Jamaica, my mind was only on the kick-off. Initially I took a few risks. At times, I pressed too hard on the accelerator and once we had a close shave with an oncoming car. It had just overtaken a van, and as it swerved around, the driver missed us by a couple of feet on the other side.

I looked across at the girl in the passenger seat. She was nearly asleep.

‘How can you relax on roads like this?’ I thought.

Noticing her seat belt was unclipped, I nudged her awake. ‘Look, if you’re going to chill, at least lock up,’ I said. ‘Otherwise if I have to break hard you’re gonna come forward.’

We came off the country tracks and hit Highway 2000 on the west side of Kingston. Jamaica’s roads were smoother there and I was enjoying the heavy purr of the engine and the surge of energy that pumped through my wheels when, out of nowhere, a flash of lightning flickered overhead. There was a clap of loud thunder. We had collided with a tropical storm and it was big. Whoosh! Rain suddenly crashed down and pounded the glass, so I flipped on the windscreen wipers and brushed the brakes, feeling the speed ease off slightly. My tyres hissed through a lake of water on the road.

Whenever it rained I often made a point of dropping gears for safety. The car had been given to me by a sponsor for winning three Olympic gold medals in the 2008 Olympics, and I’d recently visited a drivers’ school at the famous Nürburgring track in Germany to learn how to handle its powerful engine. I knew that on a slick surface, if I moved down a gear, the compression of the car would reduce my speed naturally. But pumping the brakes hard would cause the wheels to lock, and that might send me into a spin. I quickly changed down, moving my clutch foot to one side.

I was barefoot – I preferred to drive that way – and the car’s traction control was positioned next to my leg, but a funny thing had happened a few days earlier: while moving around in my seat, I’d accidentally knocked the button and the tyres had lost a little grip on the tarmac. This time, while focusing on the rain, the highway ahead, I made the same mistake and, without realising it, I knocked the traction control to ‘OFF’. Well, that’s what I think happened, because what took place next was a freak accident that nearly wiped me out for good.

I felt the car shiver a little; the body seemed to tremble at 80 miles per hour.

‘Hmm, that doesn’t feel good,’ I thought. I glanced down and checked the speedometer. It’s not slowing quickly enough!

79 …

78 …

77 …

Adrenaline came in a rush, like something bad was about to happen. That shiver, the slight tremble of the car moments earlier, had been a sign my vehicle was out of control. I wasn’t driving, I was water-skiing.

76 …

75 …

74 …

Come down, yo!

A truck rushed towards me, spray firing up from its wheels like a dozen busted fire hydrants. It was moving fast and as its carriage passed us by, another vehicle followed in the slipstream. Bang! In a heartbeat, the back of my car came around and I was out of control, sliding across the tarmac like a hockey puck on ice. I couldn’t do crap. I felt my body slipping in the seat and g-force moving me sideways. The girl next to me had woken up. Her eyes were wide and she was screaming hard.

Aaaaaaaghhhhhh!

My car careered across the lanes and I could see we were running out of road, fast. It’s not a cool thing to watch the highway falling away, a ditch rushing into view ahead. I knew right then where our asses were going to end up. I put a hand to the roof to prepare myself for the impact, wrestling the steering wheel with the other, in a desperate attempt to regain control.

It’s coming, it’s coming … Oh God, is this it?

I was terrified the car might pop up and jump into a sideways roll.

‘Please don’t flip,’ I thought. ‘Man, please don’t flip.’

We flipped.

The world turned upside down. I felt like a piece of training kit on spin cycle in the washing machine, tumbling over and over. Trees, sky, road passed in the windscreen. Trees, sky, road. Trees, sky, road … We hit the ditch with a Smash! Everything lurched forward and suddenly I was upside down. The airbags blew, all sorts of crap rattled around in the car, keys, loose change, cell phones, and then a weird silence came down, a spooky calm where nothing stirred apart from the tick-tick-ticking of the car’s indicator switch and the pouring rain outside.

I was alive. We all were, just.

‘Yo, you’re in one piece,’ I thought as I busted the door open with a hard shove.

But only God knew how, or why.

***

Sometimes people talk about close calls and near-death incidents and how they can change a man’s way of thinking for ever. For me, my smash on Highway 2000 was that moment, and after the accident I couldn’t view life in the same way again. We had survived. But how? Staggering away from the wreck should have been impossible, especially after the car had flipped over three times.

Everybody knew that speed was my thing, but I hadn’t expected velocity and horse power to so nearly cut me short, and in the hours after the crash, I experienced all the emotions usually suffered by a lucky driver in a car accident. There was guilt for my friends, who had suffered some bumps, bruises and whiplash. I felt stress, the shiver that came with realising that I’d cheated death as I replayed the disaster over and over in my head. I’d been driving fast, my wheels were out of control, and at 70 miles an hour I had flipped and bounced across the road and into a ditch.

Truth was, I should have been gone, a world phenomenon athlete cut down in his prime; a horrible newspaper headline for the world to read:

THE FASTEST MAN ON EARTH KILLED!

Learn the story of how an Olympic gold medallist and world record holder in the 100, 200 and 4x100 metres lived fast and died young!

The fact that I’d made it out alive was a miracle. I was fully functioning too, without a bruise or a mark on my entire body. Well, apart from some thorn cuts. Several long prickles had sliced open the flesh in my bare feet as I crawled from the wreckage, and the wounds were pretty deep. But those injuries felt like small change compared to what might have happened.

‘Seriously?’ I thought, when I was driven home from hospital later that day. ‘There wasn’t even a dent on me – how did that happen?’

A few weeks later, as the horror of what had happened sunk in, when I looked at the photo of my crumpled car online, something dropped with me. Something big. It was the realisation that my life had been saved by somebody else, and I didn’t mean the designer of my airbag, or the car’s seat belts. Instead, a higher power had kept me alive. God Almighty.

I took the accident to be a message from above, a sign that I’d been chosen to become The Fastest Man on Earth. My theory was that God needed me to be fit and well so I could follow the path He’d set me all those years ago when I first ran through the forest in Jamaica as a kid. I’d always believed that everything happened for a reason, because my mom had a faith in God. That faith had become more important to me as I’d got older, so in my mind the crash was a message, a warning. A sign that flashed in big, neon lights.

‘Yo, Bolt!’ it said. ‘I’ve given you a cool talent, what with this world-record breaking thing and all, and I’m going to look after you. But you need to take it seriously now. Drive careful. Check yourself.’

You know what? He had a good point. The Man Above had given me a gift and it was now down to me to make the most of it. My eyes had been opened, I had God in my corner, and He had put me on this earth to run – and faster than any athlete, ever.

Now that was pretty cool news.

I live for big championships, that’s where I come alive. In a normal race I get fired up, I’m eager to win because I’m so damn competitive, but the real desire and passion isn’t there, not fully. It’s only during a major meet that I’m really sharp and determined and have the edge I need to be an Olympic gold medallist or a world record breaker. Psychologically I’m pretty normal the rest of the time.

But give me a big stage, a fight, a challenge, and something happens – I get real. I walk an inch taller, I move a split second faster. I’d probably pop my own hamstrings to win a race. Place a big hurdle in front of me, maybe an Olympic title or an aggressive adversary like the Jamaican sprinter Yohan Blake, and I step up – I get hungry.

My school, Waldensia Primary in Sherwood Content, a village in Trelawny, was the scene of my first big challenge. I was eight years old, a gangly kid with way too much energy, and I was always on the lookout for excitement. It’s funny, though I ran around a hell of a lot, my potential on the race track only became an issue once it was spotted by one of my teachers, Mr Devere Nugent, who was a pastor and the school sports freak. I was quick on my feet even then and I loved cricket, but I never thought I could make anything of my speed other than as a bowler. One afternoon, as we played a few overs on the school field, Mr Nugent took me to one side. There was a sports day coming up and he wanted to know if I was competing in the 100 metres event.

I shrugged. ‘Maybe,’ I said.

From Grade One in Jamaica, everybody used to play sports and run against one another, but I wasn’t the fastest kid in the school back then. There was another kid at Waldensia called Ricardo Geddes, and he was quicker than me over the shorter sprints. We would run against one another in the street or on the sports field for fun, and while there wasn’t anything riding on our races, my competitive streak meant that I took every single one seriously. Whenever he beat me I always got mad, or I’d cry.

‘Yo, I can’t deal with this!’ I’d moan, often as he took me at the imaginary tape.

The biggest problem for me, even then, was I couldn’t seem to start a sprint quickly enough. It took me for ever to get up from the crouching position. Although I was too young to understand the mechanics of a race, I could tell that my height was a serious disadvantage. It took me longer to come out of the imaginary blocks than a shorter kid. Once I was in my stride I’d always catch up with Ricardo if we were running a longer distance, say 150 metres, but in a 60 metre race I knew there was no chance.

Mr Nugent figured differently.

‘You could be a sprinter,’ he said

I didn’t get it, I shrugged it off.

‘I can see real speed during your bowling run-ups,’ he said. ‘You’re quick, seriously quick.’

I wasn’t convinced. Apart from my races with Ricardo, track and field wasn’t something that had interested me before. My dad, Wellesley, was a cricket nut, and so were all my friends. Naturally, it’s all we talked about. Nobody ever conversed about the 100 metres or the long jump at school, although I could see it was a passion among the older people in Trelawny. All the fun I needed came from taking wickets. Running quick was just a handy tool for taking down batsmen, like my height and strength.

And that’s when Mr Nugent got sneaky. The man bribed me with food.

‘Bolt, if you can beat Ricardo in the school sports day race, I’ll give you a box lunch,’ he said, knowing the true way to a boy’s heart was through his stomach.

Wow, s**t had got serious! A box lunch was The Real Deal, it came packed with juicy jerk chicken, roasted sweet potatoes, rice and peas. Suddenly there was an incentive, a prize. The thought of a reward got me all excited, as did the thrill of stepping up in a big championship. I had come alive on the eve of a superstar meet for the first time. The two top stars in Waldensia Primary were going head to head and nothing was going to stop me from winning.

‘Oh, OK, Mr Nugent,’ I said. ‘If that’s how it is …’

Sports day was a big event at Waldensia, which was a typical rural Jamaican primary school. A row of small, single-storey buildings had been set atop a hill in a clearing in the middle of a stretch of tropical forest. Coconut trees and wild bush surrounded the property; the classrooms had roofs made from corrugated tin and their walls were painted in bright colours – pink, blue and yellow. There was a sports field with some goalposts, a cricket pitch and a running track, which was a bumpy stretch of grass, with lanes marked out with black lines that had been scorched into the ground with burning gasoline. At the finishing line was a shack. On the day of the race it looked to me as if the entire school had lined the lanes in support.

My heart was beating fast, my head was telling me that this was an event as big as any Olympic final. But when Mr Nugent shouted Go! something crazy happened. I got up quick and flew down that track, pushed on by the excitement of competing in a championship for the first time. At first I could hear Ricardo behind me. He was breathing hard, but I couldn’t see him out of the corner of my eye and I knew from our street races that was a good sign. As the metres flashed by, I couldn’t even hear him, which was even better news. My longer strides had taken me into a comfortable lead, and over 100 metres I was out of sight. Ricardo was nowhere near me. By the time I’d busted the tape I was miles ahead, it was over. I’d taken my first major race.

Bang! Winning was like an explosion, a rush. Joy, freedom, fun – it hit me all at once. Taking the line first felt great, especially in something as big as a school sports day race, an event that officially made me the fastest kid in Waldensia. For the first time, the buzz of serious competition had forced me to step up. World records and gold medals were a long way off, but my race against Ricardo had been a push towards getting real in track and field. I was a champ, and as I tumbled to the ground at the end of the lanes I knew one thing: being Number One felt pretty good.

***

There’s an old photo at home that makes me laugh whenever I see it. It’s of me as a kid. I’m maybe seven years old, and I’m standing in the street alongside my mom, Jennifer. Even then I was nearly shoulder high against her. I’m looking ‘silk’ in skinny black jeans and a red T-shirt. I’m clutching Mom’s hand tight, leaning in close, and the look on my face says, ‘To get to me you’ve gotta get through her first.’ It’s a happy time, a happy place.

I was a mommy’s boy back then, still am, and the only time I ever cry today is when something makes my mom sad. I hate to see her upset. Me and Pops were close, I love him dearly, but Mom and me had a special bond, probably because I was her only child and she spoilt me rotten.

Home was Coxeath, a small village near Waldensia Primary and Sherwood Content and, man, it was beautiful, a village among the lush trees and wild bush. Not a huge amount of people lived in the area; there was a house or two every few hundred metres and our old home was a simple, single-storey building rented by Dad. The pace of life was slow, real slow. Cars rarely passed through and the road was always empty. The closest thing to a traffic jam in Coxeath took place when a friend waved out in the street.

To give an idea of how remote it was, back in the day they named the whole area Cockpit Country because it was once a defensive stronghold in Jamaica used by Maroons, the runaway West Indian slaves that had settled there during the 1700s. The Maroons used the area as a base and would attack the English forts during colonial times. If their lives hadn’t been so violent, Coxeath and Sherwood Content would have been a pretty blissful place. The weather was always beautiful, the sun was hot, and even if the sky turned slightly grey, it was a tranquil spot. I remember we called the rain ‘liquid sunshine’.

Despite the climate, tourists rarely swung by, and anyone reading a guidebook would see the same thing in their travel directions: ‘Yo, you can only get there by car and the drive is pretty scary. The road winds through some heavy vegetation over a track full of potholes. On one side there’s a fast-flowing river; trees and jungle hangs down from the other and a crazy-assed chicken might run out on you at any time, so watch your step. About 30 minutes along the way is Coxeath, a small village set in the valley …’ It’s worth the effort, though. That place is my paradise.

It won’t come as a surprise to learn that the way I lived when I was young had everything to do with how I came to be an Olympic legend. There was adventure everywhere, even in my own house, and from the minute I could walk I was tearing about the home, because I was the most hyperactive kid ever. Not that anyone would have imagined that happening when I was born because, man, I came out big – nine and a half pounds big. I was such a weight that Pops later told me one of the nurses in the hospital had even made a joke about my bulk when I’d arrived.

‘My, that child looks like he’s been walking around the earth for a long time already,’ she said, holding me up in the air.

If physical size had been the first gift from Him upstairs, then the second was my unstoppable energy. From the minute I arrived, I was fast. I did not stop moving, and after I was able to crawl around as a toddler I just wanted to explore. No sofa was safe, no cupboard was out of reach and the best furniture at home became a climbing frame for me to play on. I wouldn’t sit still; I couldn’t stand in one place for longer than a second. I was always up to something, climbing on everything, and I had way too much enthusiasm for my folks to handle. At one point, probably after I’d banged my head or crashed into a door for the hundredth time, they took me to the doctors to find out what was wrong with me.

‘The boy won’t stop moving,’ cussed Pops. ‘He’s got too much energy! There must be something wrong with him.’

The doc told them that my condition was hyperactivity and there was nothing that could be done; I would grow out of it, he said. But I guess it must have been tough on them at the time, tiring even, and nobody could figure out where I’d got that crazy power from. My mom wasn’t an athlete when she was younger, nor was Pops. Sure, they used to run in school, but not to the standard I would later reach, and the only time I ever saw either one of them sprint was when Mom once chased a fowl down the street after it ran into our kitchen. It had grabbed a fish that was about to be thrown into a pot of dinner. Woah! It was like watching the American 200 and 400 Olympic gold medallist Michael Johnson tearing down the track. Mom chased that bird until it dropped the fish and ran into the woods, fearing for its feathers. I always joked that I’d got my physique from Dad (he’s over six foot tall and stick thin like me), but Mom had given me all the talent I needed.

The pace of life in Trelawny suited Mom and Pops. They were both country people and had no need to live anywhere busy like Kingston, but they worked hard. They weren’t ones for putting their foot* up, not for one second. Take Pops, he was the manager at a local coffee company. A lot of beans were produced in the Windsor area, which was several miles south of Coxeath, and it was his job to make sure they got into all the big Jamaican factories. He was always up early, travelling around the country from one parish to the next. Most nights he came home late. Sometimes, when I was little, if I went to bed before six or seven in the evening, I wouldn’t see him for days because he was always working, working, working. Whenever he came back to the house at night I was fast asleep.

Mommy had that same tough work ethic. She was a dressmaker, and the house was always full of materials, pins and thread. Everyone in the village came to our door whenever they needed their clothes repairing, and if she wasn’t feeding me, or pulling me down from the curtains, Mom was always stitching and threading cotton, or fixing buttons. Later, when I got a bit older, I was made to help her and I was soon able to hem, sew and pin materials together. Now I know what to do if ever I rip a shirt,† though I’ll still ask her to mend it because Mom has always been a fixer. If she knew how something worked, like an iron, then she could usually repair it whenever the appliance broke. I think it’s one of the reasons why I became so carefree as a kid. Mom was always ready to sort out anything I’d busted around the house.

I never went hungry living in Coxeath, because it was a farming community and we lived off whatever grew in the area, which was a lot. There were yams, bananas, coca, coconut, berries, cane, jelly trees, mangoes, oranges, guava. Everything grew in and around the backyard, so Mom never had to go to a supermarket for fruit and vegetables. There was always something in season, and I could eat whenever I wanted. Bananas would be hanging from the trees, so I just reached up and tore them down. It didn’t matter if I didn’t have any money in my pocket; if my stomach rumbled I would find a tree and pick fruits. Without realising, I was working to a diet so healthy that my body was being packed with strength and goodness.

And then the training started.

Coxeath’s wild bush was like a natural playground. I only had to step out of my front door to find something physical to do. There was always somewhere to play, always somewhere to run and always something to climb. The woods delivered an exercise programme suitable for any wannabe sprinter, with clearings to play in and assault courses made from broken coconut trees. Forget sitting around all day playing computer games like some kids do now; I loved to be outside, chasing around, exploring and running barefoot as fast as I could.

Those forests might have looked wild and crazy to an outsider, but it was a safe place to grow up. There was no crime, and nothing dangerous lurked among the sugar cane. True, there was a local snake called the Jamaican Yellow Boa, and even though it was a harmless intruder, people always freaked out if one slithered into the house. I once heard of some dude attacking one with a machete before throwing the dead body into the street. To make sure the snake was 100 per cent gone, he then flattened it with the wheels of his car and set the corpse on fire. That was pest control, Trelawny-style.

I ran everywhere, and all I wanted to do was chase around and play sports. As I got a bit older, maybe around the age of five or six, I fell in love with cricket and I’d play whenever I was allowed out in the street. Any chance I could get, I’d be batting or bowling with my friends. Mostly we used tennis balls for our games, but if we ever hit a big six into the trees or the nearby cow pen, I’d make a replacement out of rubber bands or some old string. We would then spend hours bowling and spinning our homemade balls through the air. When it came to making wickets I was even more creative – I’d get into the trunk of a banana tree and tear out a big piece of wood. Then I would carve three stumps into the bark and shape the bottom until it was flat. That way it stood up on the ground. If we were desperate, we would even play with a pile of stones or a cut-up box instead of a proper wicket.

It wasn’t all fun, though. There were chores to do for the family, even as a kid and, oh man, did I have to work sometimes! Pops was worried that I wouldn’t pick up the same work ethic that he had when he was little, so once I’d got old enough he would always tell me to do the easier jobs around the house, like the sweeping. Most of the time I was cool with it, but if ever I ran off, he would start complaining.

‘Oh, the boy is lazy,’ said Dad, time after time. ‘He should do some more work around the place.’

As I got older and stronger I was made to do more physical work around the house, and that I hated. We had no pipe water back then, so it became my job to carry buckets from the nearby stream to the family yard, where our supply was stored in four drums. Every week, if Pops was at home, I was ordered to fill them up and that was bad news because each drum held 12 buckets, which meant 48 trips to the river and back. It was tough work, as those buckets were heavy, and I would do anything to get out of carrying them.

Eventually, I figured that I couldn’t be doing 48 trips to fill the drums, it took too long, so instead I would hold two at a time and struggle home with double the weight, despite the extra, painful effort. In my mind I was cutting corners, but carrying two buckets at a time developed me physically: I could feel my arms, back and legs getting bigger with every week. The chores soon built up my muscles, and without ever going to the gym or using weights, I was taking my first steps towards developing some serious muscle. Get this: my laziness was actually making me stronger. Combined with the walking, climbing and running, my dad’s housework was helping me to become a bigger, more powerful person.

The funny thing was that Mom never forced me to do anything I didn’t want to do, especially if Pops wasn’t around. If I really grumbled hard I could cry off from bucket duty and he would never find out. The lectures would only start if ever he came home early from work to catch me slacking off. That’s when he would complain. He moaned that Mom loved me too much, and I suppose that was true, but I was her only child, so our bond was extra special.

Sometimes Dad was too strict, though. He didn’t like me to leave the house, and if he was home and I was playing he would always force me to stay in sight, usually in the yard. But whenever Pops went to work, Mom allowed me to roam free. Still, I wasn’t dumb. Wherever I was, I always listened out for Dad’s motorcycle, which would splutter noisily as the wheels came down the hill and into the village. As soon as I heard his engine, I’d drop whatever it was I was doing and sprint to the house as hard as I could, often getting back before Pops got suspicious.

Sometimes I would sneak away to play at a friend’s house which was on a patch of land away from Dad’s usual journey home. Listening out for his old bike became more difficult then, but I had a trick up my sleeve. When I snuck out of the house I would always take Brownie, the family dog, with me. The moment Pop’s bike came rumbling home, Brownie’s ears would prick up long before anyone else could hear a noise. As soon as that dog made to leave, I knew it was my cue to run. In a way, he was giving me a taste of what life would be like in the future:

Listen for the gun …

Bang!

Pop the blocks! Run! Run!

My first trainer was a dog. Ridiculous.

***

I’m going to explain how it is with my family. I have a younger brother, Sadiki, and an older sister, Christine, but we all have different mums. That’s going to sound weird to a lot of people, but that’s the way it is with home life in Jamaica sometimes. Pops had kids with two other people and my parents weren’t married when I was born. Still, it was never an issue with Mom, and whenever Sadiki and Christine came to stay with us in Coxeath they were welcomed into the home like they were her own kids.

Tasuta katkend on lõppenud.