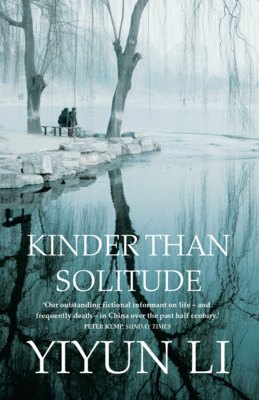

Loe raamatut: «The Vagrants»

YIYUN LI

The Vagrants

DEDICATION

For my parents

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

PART I

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

PART II

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

PART III

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ALSO BY THE AUTHOR

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

Part I

ONE

The day started before sunrise, on March 21, 1979, when Teacher Gu woke up and found his wife sobbing quietly into her blanket. A day of equality it was, or so it had occurred to Teacher Gu many times when he had pondered the date, the spring equinox, and again the thought came to him: Their daughter’s life would end on this day, when neither the sun nor its shadow reigned. A day later the sun would come closer to her and to the others on this side of the world, imperceptible perhaps to dull human eyes at first, but birds and worms and trees and rivers would sense the change in the air, and they would make it their responsibility to manifest the changing of seasons. How many miles of river melting and how many trees of blossoms blooming would it take for the season to be called spring? But such naming must mean little to the rivers and flowers, when they repeat their rhythms with faithfulness and indifference. The date set for his daughter to die was as arbitrary as her crime, determined by the court, of being an unrepentant counterrevolutionary; only the unwise would look for significance in a random date. Teacher Gu willed his body to stay still and hoped his wife would soon realize that he was awake.

She continued to cry. After a moment, he got out of bed and turned on the only light in the bedroom, an aging 10-watt bulb. A red plastic clothesline ran from one end of the bedroom to the other; the laundry his wife had hung up the night before was damp and cold, and the clothesline sagged from the weight. The fire had died in the small stove in a corner of the room. Teacher Gu thought of adding coal to the stove himself, and then decided against it. His wife, on any other day, would be the one to revive the fire. He would leave the stove for her to tend.

From the clothesline he retrieved a handkerchief, white, with printed red Chinese characters—a slogan demanding absolute loyalty to the Communist Party from every citizen—and laid it on her pillow. “Everybody dies,” he said.

Mrs. Gu pressed the handkerchief to her eyes. Soon the wet stains expanded, turning the slogan crimson.

“Think of today as the day we pay everything off,” Teacher Gu said. “The whole debt.”

“What debt? What do we owe?” his wife demanded, and he winced at the unfamiliar shrillness in her voice. “What are we owed?”

He had no intention of arguing with her, nor had he answers to her questions. He quietly dressed and moved to the front room, leaving the bedroom door ajar.

The front room, which served as kitchen and dining room, as well as their daughter Shan’s bedroom before her arrest, was half the size of the bedroom and cluttered with decades of accumulations. A few jars, once used annually to make Shan’s favorite pickles, sat empty and dusty on top of one another in a corner. Next to the jars was a cardboard box in which Teacher Gu and Mrs. Gu kept their two hens, as much for companionship as for the few eggs they laid. Upon hearing Teacher Gu’s steps, the hens stirred, but he ignored them. He put on his old sheepskin coat, and before leaving the house, he tore a sheet bearing the date of the previous day off the calendar, a habit he had maintained for decades. Even in the unlit room, the date, March 21, 1979, and the small characters underneath, Spring Equinox, stood out. He tore the second sheet off too and squeezed the two thin squares of paper into a ball. He himself was breaking a ritual now, but there was no point in pretending that this was a day like any other.

Teacher Gu walked to the public outhouse at the end of the alley. On normal days his wife would trail behind him. They were a couple of habit, their morning routine unchanged for the past ten years. The alarm went off at six o’clock and they would get up at once. When they returned from the outhouse, they would take turns washing at the sink, she pumping the water out for both of them, neither speaking.

A few steps away from the house, Teacher Gu spotted a white sheet with a huge red check marked across it, pasted on the wall of the row houses, and he knew that it carried the message of his daughter’s death. Apart from the lone streetlamp at the far end of the alley and a few dim morning stars, it was dark. Teacher Gu walked closer, and saw that the characters in the announcement were written in the ancient Li-styled calligraphy, each stroke carrying extra weight, as if the writer had been used to such a task, spelling out someone’s imminent death with unhurried elegance. Teacher Gu imagined the name belonging to a stranger, whose sin was not of the mind, but a physical one. He could then, out of the habit of an intellectual, ignore the grimness of the crime—a rape, a murder, a robbery, or any misdeed against innocent souls—and appreciate the calligraphy for its aesthetic merit, but the name was none other than the one he had chosen for his daughter, Gu Shan.

Teacher Gu had long ago ceased to understand the person bearing that name. He and his wife had been timid, law-abiding citizens all their lives. Since the age of fourteen, Shan had been wild with passions he could not grasp, first a fanatic believer in Chairman Mao and his Cultural Revolution, and later an adamant nonbeliever and a harsh critic of her generation’s revolutionary zeal. In ancient tales she could have been one of those divine creatures who borrow their mothers’ wombs to enter the mortal world and make a name for themselves, as a heroine or a devil, depending on the intention of the heavenly powers. Teacher Gu and his wife could have been her parents for as long as she needed them to nurture her. But even in those old tales, the parents, bereft when their children left them for some destined calling, ended up heartbroken, flesh-and-blood humans as they were, unable to envision a life larger than their own.

Teacher Gu heard the creak of a gate down the alley, and he hurried to leave before he was caught weeping in front of the announcement. His daughter was a counterrevolutionary, and it was a perilous situation for anyone, her parents included, to be seen shedding tears over her looming death.

When Teacher Gu returned home, he found his wife rummaging in an old trunk. A few young girls’ outfits, the ones that she had been unwilling to sell to secondhand stores when Shan had outgrown them, were laid out on the unmade bed. Soon more were added to the pile, blouses and trousers, a few pairs of nylon socks, some belonging to Shan before her arrest but most of them her mother’s. “We haven’t bought her any new clothes for ten years,” his wife explained to him in a calm voice, folding a woolen Mao jacket and a pair of matching trousers that Mrs. Gu wore only for holidays and special occasions. “We’ll have to make do with mine.”

It was the custom of the region that when a child died, the parents burned her clothes and shoes to keep the child warm and comfortable on the trip to the next world. Teacher Gu had felt for the parents he’d seen burning bags at crossroads, calling out the names of their children, but he could not imagine his wife, or himself, doing this. At twenty-eight—twenty-eight, three months, and eleven days old, which she would always be from now on—Shan was no longer a child. Neither of them could go to a crossroad and call out to her counterrevolutionary ghost.

“I should have remembered to buy a new pair of dress shoes for her,” his wife said. She placed an old pair of Shan’s leather shoes next to her own sandals on top of the pile. “She loves leather shoes.”

Teacher Gu watched his wife pack the outfits and shoes into a cloth bag. He had always thought that the worst form of grieving was to treat the afterlife as a continuity of living—that people would carry on the burden of living not only for themselves but also for the dead. Be aware not to fall into the futile and childish tradition of uneducated villagers, he thought of reminding his wife, but when he opened his mouth, he could not find words gentle enough for his message. He left her abruptly for the front room.

The small cooking stove was still unlit. The two hens in the cardboard box clucked with hungry expectation. On a normal day his wife would start the fire and cook the leftover rice into porridge while he fed the hens a small handful of millet. Teacher Gu refilled the food tin. The hens looked as attentive in their eating as did his wife in her packing. He pushed a dustpan underneath the stove and noisily opened the ash grate. Yesterday’s ashes fell into the dustpan without a sound.

“Shall we send the clothes to her now?” his wife asked. She was standing by the door, a plump bag in her arms. “I’ll start the fire when we come back,” she said when he did not reply.

“We can’t go out and burn that bag,” Teacher Gu whispered.

His wife stared at him with a questioning look.

“It’s not the right thing to do,” he said. It frustrated him that he had to explain these things to her. “It’s superstitious, reactionary—it’s all wrong.”

“What is the right thing to do? To applaud the murderers of our daughter?” The unfamiliar shrillness had returned to her voice, and her face took on a harsh expression.

“Everybody dies,” he said.

“Shan is being murdered. She is innocent.”

“It’s not up to us to decide such things,” he said. For a second he almost blurted out that their daughter was not as innocent as his wife thought. It was not a surprise that a mother was the first one to forgive and forget her own child’s wrongdoing.

“I’m not talking about what we could decide,” she said, raising her voice. “I’m asking for your conscience. Do you really believe she should die because of what she has written?”

Conscience is not part of what one needs to live, Teacher Gu thought, but before he could say anything, someone knocked on the thin wall that separated their house from their neighbors’, a protest at the noise they were making at such an early hour perhaps, or, more probably, a warning. Their next-door neighbors were a young couple who had moved in a year earlier; the wife, a branch leader of the district Communist Youth League, had come to the Gus’ house twice and questioned them about their attitudes toward their imprisoned daughter. “The party and the people have put trusting hands on your shoulders, and it’s up to you to help her correct her mistake,” the woman had said both times, observing their reactions with sharp, birdlike eyes. That was before Shan’s retrial; they had hoped then that she would soon be released, after she had served the ten years from the first trial. They had not expected that she would be retried for what she had written in her journals in prison, or that words she had put on paper would be enough evidence to warrant a death sentence.

Teacher Gu turned off the light, but the knocking continued. In the darkness he could see the light in his wife’s eyes, more fearful than angry. They were no more than birds that panicked at the first twang of a bow. In a gentle voice Teacher Gu urged, “Let me have the bag.”

She hesitated and then passed the bag to him; he hid it behind the hens’ box, the small noise of their scratching and pecking growing loud in the empty space. From the dark alley occasional creaks of opening gates could be heard, and a few crows stirred on the roof of a nearby house, their croaking carrying a strange conversational tone. Teacher Gu and his wife waited, and when there were no more knocks on the wall, he told her to take a rest before daybreak.

THE CITY OF MUDDY RIVER was named after the river that ran eastward on the southern border of the town. Downstream, the Muddy River joined other rivers to form the Golden River, the biggest river in the northeastern plain, though the Golden River did not carry gold but was rubbish-filled and heavily polluted by industrial cities on both banks. Equally misnamed, the Muddy River came from the melting snow on White Mountain. In summers, boys swimming in the river could look up from underwater at the wavering sunshine through the transparent bodies of busy minnows, while their sisters, pounding laundry on the boulders along the bank, sometimes sang revolutionary songs in chorus, their voices as clear and playful as the water.

Built on a slice of land between a mountain in the north and the river in the south, the city assumed the shape of a spindle. Expansion was limited by both the mountain and the river, but from its center the town spread to the east and the west until it tapered off to undeveloped wilderness. It took thirty minutes to walk from North Mountain to the riverbank on the south, and two hours to cover the distance between the two tips of the spindle. Yet for a town of its size, Muddy River was heavily populated and largely self-sufficient. The twenty-year-old city, a development planned to industrialize the rural area, relied on its many small factories to provide jobs and commodities for the residents. The housing was equally planned out, and apart from a few buildings of four or five stories around the city square, and a main street with a department store, a cinema, two marketplaces, and many small shops, the rest of the town was partitioned into twenty big blocks that in turn were divided into nine smaller blocks, each of which consisted of four rows of eight connected, one-storied houses. Every house, a square of fifteen feet on its sides, consisted of a bedroom and a front room, with a small front yard circled by a wooden fence or, for better-off families, a brick wall taller than a man’s height. The front alleys between the yards were a few feet wide; the back alleys allowed only one person to squeeze through. To avoid having people gaze directly into other people’s beds, the only window in the bedroom was a small square high up on the back wall. In warmer months it was not uncommon for a child to call out to his mother, and for another mother, in a different house, to answer; even in the coldest season, people heard their neighbors’ coughing, and sometimes snoring, through the closed windows.

It was in these numbered blocks that eighty thousand people lived, parents sharing, with their children, brick beds that had wood-stoves built underneath them for heating. Sometimes a grandparent slept there too. It was rare to see both grandparents in a house, as the city was a new one and its residents, recent immigrants from villages near and far, would take in their parents only when they were widowed and no longer able to live on their own.

Except for these lonely old people, the end of 1978 and the beginning of 1979 were auspicious for Muddy River as well as for the nation. Two years earlier, Chairman Mao had passed away and within a month, Madame Mao and her gang in the central government had been arrested, and together they had been blamed for the ten years of Cultural Revolution that had derailed the country. News of national policies to develop technology and the economy was delivered by rooftop loudspeakers in cities and the countryside alike, and if a man was to travel from one town to the next, he would find himself, like the blind beggar mapping this part of the province near Muddy River with his old fiddle and his aged legs, awakened at sunrise and then lulled to sleep at sundown by the same news read by different announcers; spring after ten long years of winter, these beautiful voices sang in chorus, forecasting a new Communist era full of love and progress.

In a block on the western side where the residential area gradually gave way to the industrial region, people slept in row houses similar to the Gus’, oblivious, in their last dreams before daybreak, of the parents who were going to lose their daughter on this day. It was in one of these houses that Tong woke up, laughing. The moment he opened his eyes he could no longer remember the dream, but the laughter was still there, like the aftertaste of his favorite dish, meat stewed with potatoes. Next to him on the brick bed, his parents were asleep, his mother’s hair swirled around his father’s finger. Tong tiptoed over his parents’ feet and reached for his clothes, which his mother always kept warm above the woodstove. To Tong, a newcomer in his own parents’ house, the brick bed remained a novelty, with mysterious and complex tunnels and a stove built underneath.

Tong had grown up in his maternal grandparents’ village, in Hebei Province, and had moved back to his parents’ home only six months earlier, when it was time for him to enter elementary school. Tong was not the only child, but the only one living under his parents’ roof now. His two elder brothers had left home for the provincial capitals after middle school, just as their parents had left their home villages twenty years earlier for Muddy River; both boys worked as apprentices in factories, and their futures—marriages to suitable female workers in the provincial capital, children born with legal residency in that city filled with grand Soviet-style buildings—were mapped out by Tong’s parents in their conversations. Tong’s sister, homely even by their parents’ account, had managed to marry herself into a bigger town fifty miles down the river.

Tong did not know his siblings well, nor did he know that he owed his existence to a torn condom. His father, whose patience had been worn thin by working long hours at the lathe and feeding three teenage children, had not rejoiced when the new baby arrived, a son whom many other households would have celebrated. He had insisted on sending Tong to his wife’s parents, and after a day of crying, Tong’s mother started a heroic twenty-eight-hour trip with a one-month-old baby on board an overcrowded train. Tong did not remember the grunting pigs and the smoking peasants riding side by side with him, but his piercing cries had hardened his mother’s heart. By the time she arrived at her home village, she felt nothing but relief at handing him over to her parents. Tong had seen his parents only twice in the first six years of his life, yet he had not felt deprived until the moment they plucked him out of the village and brought him to an unfamiliar home.

Tong went quietly to the front room now. Without turning on the light, he found his toothbrush with a tiny squeeze of toothpaste on it, and a basin filled with water by the washstand—Tong’s mother never forgot to prepare for his morning wash the night before, and it was these small things that made Tong understand her love, even though she was more like a kind stranger to him. He rinsed his mouth with a quick gurgle and smeared the toothpaste on the outside of the cup to reassure his mother; with one finger, he dabbed some water on his forehead and on both cheeks, the amount of washing he would allow himself.

Tong was not used to the way his parents lived. At his grandparents’ village, the peasants did not waste their money on strange-tasting toothpaste or fragrant soap. “What’s the point of washing one’s face and looking pretty?” his grandfather had often said when he told tales of ancient legends. “Live for thirty years in the wind and the dust and the rain and the snow without washing your face and you will grow up into a real man.” Tong’s parents laughed at such talk. It seemed an urgent matter for Tong’s mother that he take up the look and manner of a town boy, but despite her effort to bathe him often and dress him in the best clothes they could afford, even the youngest children in the neighborhood could tell from Tong’s village accent that he did not belong. Tong held no grudge against his parents, and he did not tell them about the incidents when he was made a clown at school. Turnip Head, the boys called him, and sometimes Garlic Mouth, or Village Bun.

Tong put on his coat, a hand-me-down from his sister. His mother had taken the trouble to redo all the buckles, but the coat still looked more like a girl’s than a boy’s. When he opened the door to the small yard, Ear, Tong’s dog, sprang from his cardboard box and dashed toward him. Ear was two, and he had accompanied Tong all the way from the village to Muddy River, but to Tong’s parents, he was nothing but a mutt, and his yellow shining pelt and dark almond-shaped eyes held little charm for them.

The dog placed his two front paws on Tong’s shoulders and made a soft gurgling sound. Tong put a finger on his lips and hushed Ear. His parents did not awake, and Tong was relieved. In his previous life in the village, Ear had not been trained to stay quiet and unobtrusive. Had it not been for Tong’s parents and the neighbors’ threats to sell Ear to a restaurant, Tong would never have had the heart to slap the dog when they first arrived. A city was an unforgiving place, or so it seemed to Tong, as even the smallest mistake could become a grave offense.

Together they ran toward the gate, the dog leaping ahead. In the street, the last hour of night lingered around the dim yellow street-lamps and the unlit windows of people’s bedrooms. Around the corner Tong saw Old Hua, the rubbish collector, bending over and rummaging in a pile with a huge pair of pliers, picking out the tiniest fragments of used paper and sticking them into a burlap sack. Every morning, Old Hua went through the city’s refuse before the crew of young men and women from the city’s sanitation department came and carted it away.

“Good morning, Grandpa Hua,” Tong said.

“Good morning,” replied Old Hua. He stood up and wiped his eyes; they were bald of eyelashes, red and teary. Tong had learned not to stare at Old Hua’s afflicted eyes. They had looked frightening at first, but when Tong had got to know the old man better, he forgot about them. Old Hua treated Tong as if he was an important person—the old man stopped working with his pliers when he talked to Tong, as if he was afraid to miss the most interesting things the boy would say. For that reason Tong always averted his eyes in respect when he talked to the old man. The town boys, however, ran after Old Hua and called him Red-eyed Camel, and it saddened Tong that the old man never seemed to mind.

Old Hua took a small stack of paper from his pocket—some ripped-off pages from newspapers and some papers with only one side used, all pressed as flat as possible—and passed them to Tong. Every morning, Old Hua kept the clean paper for Tong, who could read and then practice writing in the unused space. Tong thanked Old Hua and put the paper into his coat pocket. He looked around and did not see Old Hua’s wife, who would have been waving the big bamboo broom by now, coughing in the dust. Mrs. Hua was a street sweeper, employed by the city government.

“Where is Grandma Hua? Is she sick today?”

“She’s putting up some announcements first thing in the morning. Notice of an execution.”

“Our school is going to see it today,” Tong said. “A gun to the bad man’s head. Bang.”

Old Hua shook his head and did not reply. It was different at school, where the boys spoke of the field trip as a thrilling event, and none of the teachers opposed their excitement. “Do you know the bad man in the announcement?” Tong asked Old Hua.

“Go and look,” Old Hua said and pointed down the street. “Come back and tell me what you think.”

At the end of the street Tong saw a newly pasted announcement, the two bottom corners already coming loose in the wind. He found a rickety chair in front of a yard and dragged it over and climbed up, but still he was not tall enough, even on tiptoes, to reach the bottom of the paper. He gave up and let the corners flap on their own.

The light from the streetlamps was weak, but the eastern sky had taken on a hue of bluish white like that of an upturned fish belly. Tong read the announcement aloud, skipping the words he did not know how to pronounce but guessing their meanings without much trouble:

Counterrevolutionary Gu Shan, female, twenty-eight, was sentenced to death, with all political rights deprived. The execution will be carried out on the twenty-first of March, nineteen seventy-nine. For educational purposes, all schools and work units are required to attend the pre-execution denunciation ceremony.

At the bottom of the announcement was a signature, two out of three of whose characters Tong did not recognize. A huge check in red ink covered the entire announcement.

“You understand the announcement all right?” asked the old man, when Tong found him at another bin.

“Yes.”

“Does it say it’s a woman?”

“Yes.”

“She is very young, isn’t she?”

Twenty-eight was not an age that Tong could imagine as young. At school he had been taught stories about young heroes. A shepherd boy, seven and a half years old, not much older than Tong, led the Japanese invaders to the minefield when they asked him for directions, and he died along with the enemies. Another boy, at thirteen, protected the property of the people’s commune from robbery and was murdered by the thief. Liu Hulan, at fifteen and a half, was executed by the White Army as the youngest Communist Party member of her province, and before she was beheaded, she was reported to have sneered at the executioners and said, “She who works for Communism does not fear death.” The oldest heroine he knew of was a Soviet girl named Zoya; at nineteen she was hanged by the German Fascists, but nineteen was long enough for the life of a heroine.

“Twenty-eight is too early for a woman to die,” Old Hua said.

“Liu Hulan sacrificed her life for the Communist cause at fifteen,” replied Tong.

“Young children should think about living, not about sacrificing,” Old Hua said. “It’s up to us old people to ponder death.”

Tong found that he didn’t agree with the old man, but he did not want to say so. He smiled uncertainly, and was glad to see Ear trot back, eager to go on their morning exploration.

EVEN THE TINIEST NOISE could wake up a hungry and cold soul: the faint bark of a dog, a low cough from a neighbor’s bedroom, footsteps in the alley that transformed into thunder in Nini’s dreams while leaving others undisturbed, her father’s snore. With her good hand, Nini wrapped the thin quilt around herself, but hard as she tried, there was always part of her body exposed to the freezing air. With the limited supply of coal the family had, the fire went out every night in the stove under the brick bed, and sleeping farthest from the stove, Nini had felt the coldness seeping into her body through the thin cotton mattress and the layers of old clothes she did not take off at bedtime. Her parents slept at the other end, where the stove, directly underneath them, would keep them warm for the longest time. In the middle were her four younger sisters, aged ten, eight, five, and three, huddled in two pairs to keep each other warm. The only other person awake was the baby, who, like Nini, had no one to cuddle with for the night and who now was fumbling for their mother’s breast.

Nini got out of bed and slipped into an oversize cotton coat, in which she could easily hide her deformed hand. The baby followed Nini’s movement with bright, expressionless eyes, and then, frustrated by her futile effort, bit with her newly formed teeth. Their mother screamed, and slapped the baby without opening her eyes. “You debt collector. Eat. Eat. Eat. All you know is eating. Were you starved to death in your last life?”

The baby howled. Nini frowned. For hungry people like the baby and Nini herself, morning always came too early. Sometimes she huddled with the baby when they were both awake, and the baby would mistake her for their mother and bump her heavy head into Nini’s chest; those moments made Nini feel special, and for this reason she felt close to the baby and responsible for all that the baby could not get from their mother.

Nini limped over to the baby. She picked her up and hushed her, sticking a finger into the baby’s mouth and feeling her new, beadlike teeth. Except for Nini’s first and second sisters, who went to elementary school now, the rest of the girls, like Nini herself, did not have official names. Her parents had not even bothered to give the younger girls nicknames, as they did to Nini; they were simply called “Little Fourth,” “Little Fifth,” and, the baby, “Little Sixth.”

The baby sucked Nini’s finger hard, but after a while, unsatisfied, she let go of the finger and started to cry. Their mother opened her eyes. “Can’t you both be dead for a moment?”

Nini shuffled Little Sixth back to bed and fled before her father woke up. In the front room Nini grabbed the bamboo basket for collecting coal and stumbled on a pair of boots. A few steps into the alley, she could still hear the baby’s crying. Someone banged on the window and protested. Nini tried to quicken her steps, her crippled left leg making bigger circles than usual, and the basket, hung by the rope to her shoulder, slapped on her hip with a disturbed rhythm.

At the end of the alley Nini saw an announcement on the wall. She walked closer and looked at the huge red check. She did not recognize a single character on the announcement—her parents had long ago made it clear that for an invalid like her, education was a waste of money—but she knew by the smell that the paste used to glue the announcement to the wall was made of flour. Her stomach grumbled. She looked around for a step stool or some bricks; finding none, she set the basket on the ground with its bottom up and stepped onto it. The bottom sagged but did not give way under her weight. She reached a corner of the announcement with her good hand and peeled it off the wall. The flour paste had not dried or frozen yet, and Nini scraped the paste off the announcement and stuffed all five fingers into her mouth. The paste was cold but sweet. She scraped more of it off the announcement. She was sucking her fingers when a feral cat pounced off a wall and stopped a few feet away, examining her with silent menace. She hurried down from the basket, almost falling onto her bad foot, and sending the cat scurrying away.