Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «The Feast of Love»

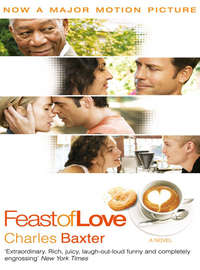

CHARLES BAXTER

The Feast of Love

DEDICATION

In loving memory of my brother

THOMAS HOOKER BAXTER

(1939–1998)

Yes, there were times when I forgot not only who I was, but that I was, forgot to be.

—SAMUEL BECKETT, Molloy

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Beginnings

Preludes

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Middles

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Ends

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Postludes

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Praise

By the Same Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

BEGINNINGS

PRELUDES

THE MAN—ME, this pale being, no one else, it seems—wakes in fright, tangled up in the sheets.

The darkened room, the half-closed doors of the closet and the slender pine-slatted lamp on the bedside table: I don’t recognize them. On the opposite side of the room, the streetlight’s distant luminance coating the window shade has an eerie unwelcome glow. None of these previously familiar objects have any familiarity now. What’s worse, I cannot remember or recognize myself. I sit up in bed—actually, I lurch in mild sleepy terror toward the vertical. There’s a demon here, one of the unnamed ones, the demon of erasure and forgetting. I can’t manage my way through this feeling because my mind isn’t working, and because it, the flesh in which I’m housed, hasn’t yet become me.

Looking into the darkness, I have optical floaters: there, on the opposite wall, are gears turning separately and then moving closer to one another until their cogs start to mesh and rotate in unison.

Then I feel her hand on my back. She’s accustomed by now to my night amnesias, and with what has become an almost automatic response, she reaches up sleepily from her side of the bed and touches me between the shoulder blades. In this manner the world’s objects slip back into their fixed positions.

“Charlie,” she says. Although I have not recognized myself, apparently I recognize her: her hand, her voice, even the slight saltine-cracker scent of her body as it rises out of sleep. I turn toward her and hold her in my arms, trying to get my heart rate under control. She puts her hand to my chest. “You’ve been dreaming,” she says. “It’s only a bad dream.” Then she says, half-asleep again, “You have bad dreams,” she yawns, “because you don’t …” Before she can finish the sentence, she descends back into sleep.

I get up and walk to the study. I have been advised to take a set of steps as a remedy. I have “identity lapses,” as the doctor is pleased to call them. I have not found this clinical phrase in any book. I think he made it up. Whatever they are called, these lapses lead to physical side effects: my heart is still thumping, and I can hardly sit or lie still.

I write my name, Charles Baxter, my address, the county, and the state in which I live. I concoct a word that doesn’t exist in our language but still might have a meaning or should have one: glimmerless. I am glimmerless. I write down the word next to my name.

ON THE FIRST FLOOR near the foot of the stairs, we have placed on the wall an antique mirror so old that it can’t reflect anything anymore. Its surface, worn down to nubbled grainy gray stubs, has lost one of its dimensions. Like me, it’s glimmerless. You can’t see into it now, just past it. Depth has been replaced by texture. This mirror gives back nothing and makes no productive claim upon anyone. The mirror has been so completely worn away that you have to learn to live with what it refuses to do. That’s its beauty.

I have put on jeans, a shirt, shoes. I will take a walk. I glide past the nonmirroring mirror, unseen, thinking myself a vampire who soaks up essences other than blood. I go outside to Woodland Drive and saunter to the end of the block onto a large vacant lot. Here I am, a mere neighbor, somnambulating, harmless, no longer a menace to myself or to anyone else, and, stage by stage, feeling calmer now that I am outside.

As all the neighbors know, no house will ever be built on the ground where I am standing because of subsurface problems with water drainage. In the fladands of Michigan the water stays put. The storm sewers have proven to be inadequate, with the result that this property, at the base of the hill on which our street was laid, always floods following thunderstorms and stays wet for weeks. The neighborhood kids love it. After rains they shriek their way to the puddles.

ABOVE ME in the clear night sky, the moon, Earth’s mad companion, is belting out show tunes. A Rodgers and Hart medley, this is, including “Where or When.” The moon has a good baritone voice. No: someone from down the block has an audio system on. Apparently I am still quite sleepy and disoriented. The moon, it seems, is not singing after all.

I turn away from the vacant lot and head east along its edge, taking the sidewalk that leads to the path into what is called Pioneer Woods. These woods border the houses on my street. I know the path by heart. I have taken walks on this path almost every day for the last twenty years. Our dog, Tasha, walks through here as mechanically as I do except when she sees a squirrel. In the moonlight the path that I am following has the appearance of the tunnel that Beauty walks through to get to the Beast, and though I cannot see what lies at the other end of the tunnel, I do not need to see it. I could walk it blind.

ON THE PATH NOW, urged leftward toward a stand of maples, I hear the sound of droplets falling through the leaves. It can’t be raining. There are still stars visible intermittently overhead. No: here are the gypsy moths, still in their caterpillar form, chewing at the maple and serviceberry leaves, devouring our neighborhood forest leaf by leaf. Night gives them no rest. The woods have been infested with them, and during the day the sun shines through these trees as if spring were here, bare stunned nubs of gnawed and nibbled leaves casting almost no shade on the ground, where the altered soil chemistry, thanks to the caterpillars’ leavings, has killed most of the seedlings, leaving only disagreeably enlarged thorny and deep-rooted thistles, horror-movie phantasm vegetation with deep root systems. The trees are coated, studded, with caterpillars, their bare trunks hairy and squirming. I can barely see them but can hear their every scrape and crawl.

The city has sprayed this forest with Bacillus thuringiensis, two words I love to say to myself, and the bacillus has killed some of these pests; their bodies lie on the path, where my seemingly adhesive shoes pick them up. I can feel them under my soles in the dark as I walk, squirming semiliquid life. Squish, squoosh. And in my night confusion it is as if I can hear the leaves being gnawed, the forest being eaten alive, shred by shred. I cannot bear it. They are not mild, these moths. Their appetites are blindingly voracious, obsessive. An acquaintance has told me that the Navahos refer to someone with an emotional illness as “moth crazy.”

ON THE OTHER SIDE of the woods I come out onto the edge of a street, Stadium Boulevard, and walk down a slope toward the corner, where a stoplight is blinking red in two directions. I turn east and head toward the University of Michigan football stadium, the largest college football stadium in the country. The greater part of it was excavated below ground; only a small part of its steel and concrete structure is visible from here, the corner of Stadium and Main, just east of Pioneer High School. Cars pass occasionally on the street, their drivers hunched over, occasionally glancing at me in a fearful or predatory manner. Two teenagers out here are skateboarding in the dark, clattering over the pavement, doing their risky and amazing ankle-busting curb jumping. They grunt and holler. Both white, they have fashioned Rasta-wear for themselves, dreads and oversized unbuttoned vests over bare skin. I check my watch. It is 1:30. I stop to make sure that no patrol cars are passing and then make my way through the turnstiles. The university has planned to build an enormous iron fence around this place, but it’s not here yet. I am trespassing now and subject to arrest. After entering the tunneled walkway of Gate 19, I find myself at the south end zone, in the kingdom of football.

Inside the stadium, I feel the hushed moonlight on my back and sit down on a metal bench. The August meteor shower now seems to be part of this show. I am two thirds of the way up. These seats are too high for visibility and too coldly metallic for comfort, but the place is so massive that it makes most individual judgments irrelevant. Like any coliseum, it defeats privacy and solitude through sheer size. Carved out of the earth, sized for hordes and giants, bloody injuries and shouting, and so massive that no glance can take it all in, the stadium can be considered the staging ground for epic events, and not just football: in 1964, President Lyndon Baines Johnson announced his Great Society program here.

On every home-game Saturday in the fall, blimps and biplanes pulling advertising banners putter in semicircles overhead. Starting about three hours before kickoff, our street begins to be clogged with parked cars and RVs driven by midwesterners in various states of happy pre-inebriation, and when I rake the leaves in my back yard I hear the tidal clamor of the crowd in the distance, half a mile away. The crowd at the game is loudly traditional and antiphonal: one side of the stadium roars GO and the other side roars BLUE. The sounds rise to the sky, also blue, but nonpartisan.

The moonlight reflects off the rows of stands. I look down at the field, now, at 1:45 in the morning. A midsummer night’s dream is being enacted down there.

This old moon wanes! She lingers my desires and those of a solitary naked couple, barely visible down there right now on the fifty-yard line, making love, on this midsummer night.

They are making soft distant audibles.

BACK OUT ON THE SIDEWALK, I turn west and walk toward Allmendinger Park. I see the park’s basketball hoops and tennis courts and monkey bars illuminated dimly by the streetlight. Near the merry-go-round, the city planners have bolted several benches into the ground for sedentary parents watching their children. I used to watch my son from that very spot. As I stroll by on the sidewalk, I think I see someone, some shadowy figure in a jacket, emerging as if out of a fog or mist, sitting on a bench accompanied by a dog, but certainly not watching any children, this man, not at this time of night, and as I draw closer, he looks up, and so does the dog, a somewhat nondescript collie-Labrador-shepherd mix. I know this dog. I also know the man sitting next to him. I have known him for years. His arms are flung out on both sides of the bench, and his legs are crossed, and in addition to the jacket (a dark blue Chicago Bulls windbreaker), he’s wearing a baseball hat, as if he were not quite adult, as if he had not quite given up the dreams of youth and athletic grace and skill. His name is Bradley W. Smith.

His chinos are one size too large for him—they bag around his hips and his knees—and he’s wearing a shirt with a curious design that I cannot quite make out, an interlocking M. C. Escher giraffe pattern, giraffes linked to giraffes, but it can’t be that, it can’t be what I think it is. In the dark my friend looks like an exceptionally handsome toad. The dog snaps at a moth, then puts his head on his owner’s leg. I might be hallucinating the giraffes on the man’s shirt, or I might simply be mistaken. He glances at me in the dark as I sit down next to him on the bench.

“Hey,” he says, “Charlie. What the hell are you doing out here? What’s up?”

ONE

“HEY,” HE SAYS, “Charlie. What the hell are you doing here? What’s up?”

Sitting down next to him, I can see his glasses, which reflect the last crescent of the moon and a dim shooting star. In the half-dark he has a handsome mild face, thick curly hair and an easy disarming smile, like that of a bank loan officer who has not quite decided whether your credit history is worthy of you. His eyes are large and pensive, toadlike. I realize quickly that if he is sitting out here on this park bench, now, he must be a rather unlucky man, insomniac or haunted or heartsick.

“Hey, Bradley,” I say. “Not much. Walkin’ around. It’s a midsummer night, and I’ve got insomnia. I see you’re still awake, too.”

“Yeah,” he says, nodding unnecessarily, “that’s the truth.”

We both wait. Finally I ask him, “How come you’re up?”

“Me? Oh, I found myself working late on a window in my house. The sash weight broke loose from the pulley and I’ve been trying to get it out from inside the wall.”

“Difficult job.”

“Right. Anyway, I quit that, and I’ve been walking Bradley the dog, since I couldn’t fix the window. Do you remember this dog?”

“His name is … what?”

“Bradley. I just told you. Exact same as mine. It’s easier to call him ‘Junior.’ That way, there’s no confusion. He’s my company. But you’re not sleeping either, right?” he asks, staring off into the middle distance as if he were talking to himself, as if I were an intimation of him. “That makes the two of us.” He leans back. “Three of us, if you count the dog.”

“I woke up,” I tell him, “and I was seeing things.”

“What things?”

“I don’t want to talk about it,” I tell him.

“Okay.”

“Oh, you know. I was seeing spots.”

“Spots?”

“Yes. Like spots in front of your eyes. But these were more like cogs.”

“You mean like gears or something?”

“I guess so. Wheels with cogs turning, and then getting closer to each other, so that they all turned together, their gears meshing.” I rub my arm, mosquito bite.

In the shadows, one side of his face seems about to collapse, as if the effort to keep up appearances has finally failed and daylight optimism has abandoned him. He sighs and scratches Junior behind the ears. In response, the dog smiles broadly. “Gears. I never heard of that one. I guess you don’t sleep any better than I do. We’re two members of the insomnia army.” He stretches now and reaches up to grab some air. “A brotherhood. And sisterhood. Did you know that Marlene Dietrich was a great insomniac?”

“No, I didn’t.”

“Do you know what she did to keep herself occupied at night?”

“No, I don’t.”

“She baked cakes,” he tells me. “I read this in the Sunday paper. She baked angel food cakes and then in the daytime she gave them away to her friends. Marlene Dietrich. She looked like she did, those eyes of hers, because she couldn’t sleep well. Now me,” he says, rearranging himself on the bench, “I just sit still here, very still, you know, like what’s-his-name, the compassionate Buddha, thinking about the world, the one you and I live in, and I come to conclusions. Conclusions and remedies. Lately I’ve been thinking of extreme remedies. For extreme problems we need extreme remedies. That’s the phrase.”

“‘Extreme remedies’? What d’you mean? And don’t go putting me in your brotherhood. I’m just on a neighborhood stroll.”

“‘A neighborhood stroll’! Man,” he says, pointing a revolver-finger at me, “you’ll be lucky if a patrol car doesn’t pick you up.”

“Oh, I’m respectable,” I tell him.

“Listen to yourself. ‘Respectable’! You’re dressed like a vagabond. A goon. It’s illegal to walk around at night in this town, didn’t you know that?” He stands up to give me an inquiring once-over. He apparently doesn’t like what he sees. “It makes you look like a danger to public safety. Vagrancy! They’ll haul your ass down to jail, man. They don’t allow it anymore unless you have a dog with you. The dog”—he nods at his own dog—“makes it legal. The dog makes it legitimate. I have a dog. You should have a dog. It’s best to have an upper-class dog like a collie or a golden retriever, a licensed dog. But any dog will do. Believe me, the happy people are all at home and asleep, snuggled together in their dreams.” He says this phrase with contempt. “All the lucky ones.” He sits down but still seems agitated. “The goddamn lucky ones … What’s your trouble?” He grins at me gnomishly. “Conscience bothering you? Got a writing block?”

“No. I told you. I woke up disoriented. It happens all the time. Thinking about a book, I guess. I have to walk it off. Anyway, I already have a dog.”

“I didn’t know that. Where is it?” He glances around, pretending to search.

“Sleeping. She doesn’t like to walk with me at night. She doesn’t like how disoriented I am.”

“Smart. So what you’re saying is, you don’t know where you are? Is that it?”

“Right. I know where I am now.”

“Maybe you’re too involved with fiction. Well, don’t mind me. But listen, since we’re here, tell me: how does this new book of yours begin? What’s the first line?”

I start to pick some chewing gum off my shoe. “Nope. I don’t do that. I don’t give things like that away.”

“Come on. I’m your neighbor, Charlie. I’ve known you, what is it—?”

“Twelve years,” I say.

“Twelve years. You think I’m going to steal your line? I would never do that. I don’t do that. I’m not a writer, thank God. I’m a businessman. And an artist. Go ahead. Just tell me. Tell me how your novel starts.”

I sit back for a moment. “‘The man,’” I recite, “‘me—no one else, it seems—wakes in fright.’”

He kicks the toe of his shoe in the dirt and tanbark, and Junior sniffs at it. Now Bradley tries out a sympathetic tone. “That’s the line?”

“That’s the line. It’s still in rough draft. Actually, it’s just in my head.”

He nods. “Kind of melodramatic, though, right? I thought it was a cardinal rule not to start a novel with someone waking up in bed. And what’s all this about fright? Do you really awaken in terror? That doesn’t seem like you at all. And by the way I believe the word is awakens.”

Irritated, I stare at him. “When did you become Mr. Usage? All right, I’ll revise it. Besides, I do wake in terror. Ask my wife.”

“No, I would never do that. What’s the book called?”

“I have no idea.”

“You should call it The Feast of Love. I’m the expert on that. I should write that book. Actually, I should be in that book. You should put me into your novel. I’m an expert on love. I’ve just broken up with my second wife, after all. I’m in an emotional tangle. Maybe I’d shoot myself before the final chapter. Your readers would wonder about the outcome. Yeah, the feast of love. It certainly isn’t what I expected when I was in high school and I was imagining what love was going to be, honeymoon jaunts, joy forever and that sort of thing.”

I glance at the dog, who is yawning in my face. I bore this dog. “Aren’t you going out with a doctor now? Some new woman?”

“That’s private.”

“Hey, you came up with the title, and then you decide I can’t have it because it’s a metaphor? And you want to be a character in this book, and you won’t give me the details of your love life?”

“Metaphor my ass. I don’t know. Call it The Feast of Love. I know: call it Unchain My Heart. Now there’s a good title. Call it anything you want to. But remember: metaphors mean something,” he says, sitting up. Junior also sits up. “You remember Kathryn, my ex? My first ex? When Kathryn called me a toad, which she did sometimes to punish me, I’m sure she chose that metaphor carefully. She took great care with her language. She was fastidious. She probably searched for that metaphor all day. She went shopping for metaphors, Kathryn did. X marked the spot where she found them. Then she displayed them, all these metaphors, to me. After a while it became her nickname for me, as in ‘Toad, my love, would you pass the potatoes?’ They were always about me, these metaphors, as it turned out. She got that one from The Wind in the Willows, her favorite book. You know: Mr. Toad?”

He says this in his low voice and surveys the gloom of the playground, and now, in the dark, he does sound a bit like a toad.

“It could have been worse,” he informs me. “A toad has dignity.” He looks around. Then he breaks into song.

The Clever Men at Oxford Know all that there is to be knowed But they none of them know one half as much As intelligent Mr. Toad.

“Anyway, I got on her nerves after a while. And of course, she was a lesbian, sort of, a little bit of one, a sexual tourist, but we could have handled the tourism part, given enough time. At least that’s what I thought. The real problem was that she didn’t like how inconsistent I was. She thought I was the man of a thousand faces, nice in the morning, not so nice at night. Men like me exasperated her. She once called me the Lon Chaney of the Midwest, the Lon Chaney with the monster light bulb burning inside his cheekbone. The phantom, she called me, of the opera.” He waits for a moment. “What opera? There’s no opera in this town.”

He stares up into the night sky, then continues. “Well, at least I was a star. You know, women admire physical beauty in men more than they claim they do.” He says this to me conspiratorially, as if imparting a deep secret. He sighs. “Don’t kid yourself on that score.”

“I would never kid myself about that,” I tell him. “This isn’t Diana you’re talking about? This is Kathryn?”

“No,” he sighs angrily, “not Diana. Of course not. No, goddamn it, I told you: this was my first. My starter marriage. You met her, I know that. Kathryn.”

“No,” I say, “I don’t remember her. But you weren’t married to Diana so long either.”

“Maybe not,” he mutters, “but I loved her. Especially after we were divorced. A fate-prank. She loved someone else before I married her and she loved him while I was married to her, and she loves him now. The dog and I sit out here and we think about her, and about the business that I own, the coffee business. I don’t actually know what the dog thinks about.” A little air pocket of silence opens up between us. I hear him breathing, and I look down at his clasped hands. One of the hands reaches into his pants pocket for a dog treat, which he hands to Junior, who gobbles it down.

“You shouldn’t do that. Get lost in nostalgia, I mean. But Diana was beautiful,” I say.

“She still is. And I’m not nostalgic.”

“But she was unfaithful to you,” I tell him. “You can’t love someone who does that.”

“I almost could. She was powerful. She had me in a kind of spell, I’m not kidding.” He looks straight at me. “Nearly a goddess, Diana. I could let her destroy me. In flames. I’d go down in flames watching her.”

Just as he finishes this sentence, some noise—it sounds like a crow cawing—filters down to us from very high in the nearby trees. Odd: I cannot remember ever hearing a crow at night. At the same time that I have this thought, I hear a man laugh twice, distantly, from the houses behind us. A horribly mean laugh, this is. It makes the hair on the back of my neck stand up.

“Oh, by the way,” I say, “I just came from the football stadium. Guess what I saw.”

“They’re going to put a big fence around that place.” He laughs. “Didn’t you know that? A big fence. With a gigantic new Vegas-style scoreboard. People like you keep trying to get in.”

“There’s no fence around it now,” I tell him.

“I can see where this is going,” Bradley snorts. “Walking around at night, you’re soaking up material for your book, The Feast of Love, and what to your wandering eyes should appear? I know exactly what appeared. You saw some kids who’d snuck into the stadium and were actively naked on the fifty-yard line.”

“Well, yes.” I wait, disappointed. “How did you know? I mean, I thought it was rather sweet. And you know, I was touched.”

“Touched.”

“It’s hard to describe. Their …”

His curiosity gleams at me from his permanently love-struck face.

“Oh, you know,” I say. “The waning moon was shining down on them. Like A Midsummer Night’s Dream, or something of the sort.”

“All right, sure. I know. Love on the field of play. Happens all the time, though,” he says in a calmer and possibly sedated voice. For a moment I wonder if he’s on Prozac. “Didn’t you know that? I grew up around here, so I should know. Kids sneaking in, it’s a big deal for them, they can point to the fifty-yard line and say, ‘Hey, man, guess what I did down there with my girlfriend? That’s where I got laid, Bub, right down there where that big guy is being taken off on a stretcher.’”

“Well,” I say, “I gotta go.”

He grabs my arm in a strong grip. “No you don’t. That’s the most ridiculous claim I ever heard. It’s two in the morning. You don’t have to go anywhere.”

“My wife’s expecting me back.”

He sits up suddenly. “Listen, Charlie,” he says. “I’ve got an idea. It’ll solve all your problems and it’ll solve mine. Why don’t you let me talk? Let everybody talk. I’ll send you people, you know, actual people, for a change, like for instance human beings who genuinely exist, and you listen to them for a while. Everybody’s got a story, and we’ll just start telling you the stories we have.”

“What do you think I am, an anthropologist?” I mull it over. “No, sorry, Bradley, it won’t work. I’d have to fictionalize you. I’d have to fictionalize this dog here.” I pat Junior on the head. Junior smiles again: a very stupid and very friendly dog, but not a character in a novel.

“Well, change your habits. And, believe me, it will work. Listen to this.” He clears his throat. “Okay. Chapter One. Every relationship has at least one really good day …”