Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «Charlotte’s Web»

Copyright

This ebook edition first published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books, 2015

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is www.harpercollins.co.uk

Charlotte’s Web

Text copyright © E.B. White, 1952

Text copyright © renewed 1980 by E.B. White

Illustration copyright © renewed 1980 by the Estate of Garth Williams

Colourisations copyright © 1999 by the Estate of Garth Williams

E.B. White and Garth Williams assert the moral right to be identified as the author and illustrator of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © MARCH 2015 ISBN: 9780008139414

Version: 2015-03-05

Contents

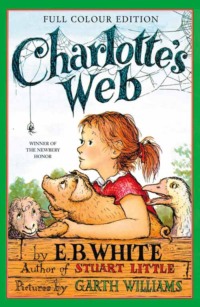

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

1. Before Breakfast

2. Wilbur

3. Escape

4. Loneliness

5. Charlotte

6. Summer Days

7. Bad News

8. A Talk at Home

9. Wilbur’s Boast

10. An Explosion

11. The Miracle

12. A Meeting

13. Good Progress

14. Dr Dorian

15. The Crickets

16. Off to the Fair

17. Uncle

18. The Cool of the Evening

19. The Egg Sac

20. The Hour of Triumph

21. Last Day

22. A Warm Wind

Keep Reading

About the Author

About the Illustrator

Other Books By

About the Publisher

1. Before Breakfast

‘WHERE’S Papa going with that axe?’ said Fern to her mother as they were setting the table for breakfast.

‘Out to the hoghouse,’ replied Mrs Arable. ‘Some pigs were born last night.’

‘I don’t see why he needs an axe,’ continued Fern, who was only eight.

‘Well,’ said her mother, ‘one of the pigs is a runt. It’s very small and weak, and it will never amount to anything. So your father has decided to do away with it.’

‘Do away with it?’ shrieked Fern. ‘You mean kill it? Just because it’s smaller than the others?’

Mrs Arable put a pitcher of cream on the table. ‘Don’t yell, Fern!’ she said. ‘Your father is right. The pig would probably die anyway.’

Fern pushed a chair out of the way and ran outdoors. The grass was wet and the earth smelled of springtime. Fern’s sneakers were sopping by the time she caught up with her father.

‘Please don’t kill it!’ she sobbed. ‘It’s unfair.’

Mr Arable stopped walking.

‘Fern,’ he said gently, ‘you will have to learn to control yourself.’

‘Control myself?’ yelled Fern. ‘This is a matter of life and death, and you talk about controlling myself.’ Tears ran down her cheeks and she took hold of the axe and tried to pull it out of her father’s hand.

‘Fern,’ said Mr Arable, ‘I know more about raising a litter of pigs than you do. A weakling makes trouble. Now run along!’

‘But it’s unfair,’ cried Fern. ‘The pig couldn’t help being born small, could it? If I had been very small at birth, would you have killed me?’

Mr Arable smiled. ‘Certainly not,’ he said, looking down at his daughter with love. ‘But this is different. A little girl is one thing, a little runty pig is another.’

‘I see no difference,’ replied Fern, still hanging on to the axe. ‘This is the most terrible case of injustice I ever heard of.’

A queer look came over John Arable’s face. He seemed almost ready to cry himself.

‘All right,’ he said. ‘You go back to the house and I will bring the runt when I come in. I’ll let you raise it on a bottle, like a baby. Then you’ll see what trouble a pig can be.’

When Mr Arable returned to the house half an hour later, he carried a carton under his arm. Fern was upstairs changing her sneakers. The kitchen table was set for breakfast, and the room smelt of coffee, bacon, damp plaster, and wood smoke from the stove.

‘Put it on her chair!’ said Mrs Arable. Mr Arable set the carton down at Fern’s place. Then he walked to the sink and washed his hands and dried them on the roller towel.

Fern came slowly down the stairs. Her eyes were red from crying. As she approached her chair, the carton wobbled, and there was a scratching noise. Fern looked at her father. Then she lifted the lid of the carton. There, inside, looking up at her, was the newborn pig. It was a white one. The morning light shone through its ears, turning them pink.

‘He’s yours,’ said Mr Arable. ‘Saved from an untimely death. And may the good Lord forgive me for this foolishness.’

Fern couldn’t take her eyes off the tiny pig. ‘Oh,’ she whispered. ‘Oh, look at him! He’s absolutely perfect.’

She closed the carton carefully. First she kissed her father, then she kissed her mother. Then she opened the lid again, lifted the pig out, and held it against her cheek. At this moment her brother Avery came into the room. Avery was ten. He was heavily armed – an air rifle in one hand, a wooden dagger in the other.

‘What’s that?’ he demanded. ‘What’s Fern got?’

‘She’s got a guest for breakfast,’ said Mrs Arable. ‘Wash your hands and face, Avery!’

‘Let’s see it!’ said Avery, setting his gun down. ‘You call that miserable thing a pig? That’s a fine specimen of a pig – it’s no bigger than a white rat.’

‘Wash up and eat your breakfast, Avery!’ said his mother. ‘The school bus will be along in half an hour.’

‘Can I have a pig too, Pop?’ asked Avery.

‘No, I only distribute pigs to early risers,’ said Mr Arable. ‘Fern was up at daylight, trying to rid the world of injustice. As a result, she now has a pig. A small one, to be sure, but nevertheless a pig. It just shows what can happen if a person gets out of bed promptly. Let’s eat!’

But Fern couldn’t eat until her pig had had a drink of milk. Mrs Arable found a baby’s nursing bottle and a rubber nipple. She poured warm milk into the bottle, fitted the nipple over the top, and handed it to Fern. ‘Give him his breakfast!’ she said.

A minute later, Fern was seated on the floor in the corner of the kitchen with her infant between her knees, teaching it to suck from the bottle. The pig, although tiny, had a good appetite and caught on quickly.

The school bus honked from the road.

‘Run!’ commanded Mrs Arable, taking the pig from Fern and slipping a doughnut into her hand. Avery grabbed his gun and another doughnut.

The children ran out to the road and climbed into the bus. Fern took no notice of the others in the bus. She just sat and stared out of the window, thinking what a blissful world it was and how lucky she was to have entire charge of a pig. By the time the bus reached school, Fern had named her pet, selecting the most beautiful name she could think of.

‘Its name is Wilbur,’ she whispered to herself.

She was still thinking about the pig when the teacher said: ‘Fern, what is the capital of Pennsylvania?’

‘Wilbur,’ replied Fern, dreamily. The pupils giggled. Fern blushed.

2. Wilbur

FERN LOVED Wilbur more than anything. She loved to stroke him, to feed him, to put him to bed. Every morning, as soon as she got up, she warmed his milk, tied his bib on, and held the bottle for him. Every afternoon, when the school bus stopped in front of her house, she jumped out and ran to the kitchen to fix another bottle for him. She fed him again at suppertime, and again just before going to bed. Mrs Arable gave him a feeding around noontime each day, when Fern was away in school. Wilbur loved his milk, and he was never happier than when Fern was warming up a bottle for him. He would stand and gaze up at her with adoring eyes.

For the first few days of his life, Wilbur was allowed to live in a box near the stove in the kitchen. Then, when Mrs Arable complained, he was moved to a bigger box in the woodshed. At two weeks of age, he was moved outdoors. It was apple-blossom time, and the days were getting warmer. Mr Arable fixed a small yard specially for Wilbur under an apple tree, and gave him a large wooden box full of straw, with a doorway cut in it so he could walk in and out as he pleased.

‘Won’t he be cold at night?’ asked Fern.

‘No,’ said her father. ‘You watch and see what he does.’

Carrying a bottle of milk, Fern sat down under the apple tree inside the yard. Wilbur ran to her and she held the bottle for him while he sucked. When he had finished the last drop, he grunted and walked sleepily into the box. Fern peered through the door. Wilbur was poking the straw with his snout. In a short time he had dug a tunnel in the straw. He crawled into the tunnel and disappeared from sight, completely covered with straw. Fern was enchanted. It relieved her mind to know that her baby would sleep covered up, and would stay warm.

Every morning after breakfast, Wilbur walked out to the road with Fern and waited with her till the bus came. She would wave goodbye to him, and he would stand and watch the bus until it vanished round a turn. While Fern was in school, Wilbur was shut up inside his yard. But as soon as she got home in the afternoon, she would take him out and he would follow her round the place. If she went into the house, Wilbur went too. If she went upstairs, Wilbur would wait at the bottom step until she came down again. If she took her doll for a walk in the doll carriage, Wilbur followed along. Sometimes, on these journeys, Wilbur would get tired, and Fern would pick him up and put him in the carriage alongside the doll. He liked this. And if he was very tired, he would close his eyes and go to sleep under the doll’s blanket. He looked cute when his eyes were closed, because his lashes were so long. The doll would close her eyes, too, and Fern would wheel the carriage very slowly and smoothly so as not to wake her infants.

One warm afternoon, Fern and Avery put on bathing suits and went down to the brook for a swim. Wilbur tagged along at Fern’s heels. When she waded into the brook, Wilbur waded in with her. He found the water quite cold – too cold for his liking. So while the children swam and played and splashed water at each other, Wilbur amused himself in the mud along the edge of the brook, where it was warm and moist and delightfully sticky and oozy.

Every day was a happy day, and every night was peaceful.

Wilbur was what farmers call a spring pig, which simply means that he was born in springtime. When he was five weeks old, Mr Arable said he was now big enough to sell, and would have to be sold. Fern broke down and wept. But her father was firm about it. Wilbur’s appetite had increased; he was beginning to eat scraps of food in addition to milk. Mr Arable was not willing to provide for him any longer. He had already sold Wilbur’s ten brothers and sisters.

‘He’s got to go, Fern,’ he said. ‘You have had your fun raising a baby pig, but Wilbur is not a baby any longer and he has got to be sold.’

‘Call up the Zuckermans,’ suggested Mrs Arable to Fern. ‘Your Uncle Homer sometimes raises a pig. And if Wilbur goes there to live, you can walk down the road and visit him as often as you like.’

‘How much money should I ask for him?’ Fern wanted to know.

‘Well,’ said her father, ‘he’s a runt. Tell your Uncle Homer you’ve got a pig you’ll sell for six dollars, and see what he says.’

It was soon arranged. Fern phoned and got her Aunt Edith, and her Aunt Edith hollered for Uncle Homer and Uncle Homer came in from the barn and talked to Fern. When he heard that the price was only six dollars, he said he would buy the pig. Next day Wilbur was taken from his home under the apple tree and went to live in a manure pile in the cellar of Zuckerman’s barn.

Tasuta katkend on lõppenud.