Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «We Are Not Ourselves»

Copyright

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street,

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate in 2014

First published in the United States by Simon & Schuster, Inc. in 2014

Copyright © 2014 by Matthew Thomas

Matthew Thomas asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

The Author and Publishers are committed to respecting the intellectual property rights of others and have made all reasonable efforts to trace the copyright owners of the images reproduced, and to provide appropriate acknowledgement, within this book. In the event that any untraceable copyright owners come forward after the publication of this book, the Author and Publishers will use all reasonable endeavours to rectify the position accordingly.

“Touch me.” Copyright © 1995 by Stanley Kunitz, from Passing Through: The Later Poems New and Selected by Stanley Kunitz. Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

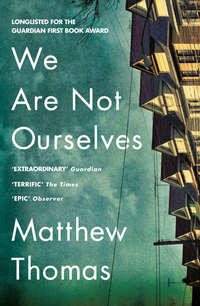

Cover photographs © Kim Sohee/Getty Images (houses); Mark Owen/Arcangel Images (sky).

Cover design by Christopher Lin

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007548217

Ebook Edition © August 2014 ISBN: 9780007548224

Version: 2015-02-20

Dedication

To Joy

Darling, do you remember

the man you married? Touch me,

remind me who I am.

—Stanley Kunitz

We are not ourselves

When nature, being oppressed, commands the mind

To suffer with the body.

—King Lear

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Part I: Days under Sun and Rain 1951–1982

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Part II: The Salad Days Thursday, October 23, 1986

Chapter 14

Part III: Breathe the Rich Air 1991

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Part IV: Level, Solid, Square and True 1991–1995

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Part V: Desire Is Full of Endless Distances 1996

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Chapter 72

Chapter 73

Chapter 74

Chapter 75

Chapter 76

Chapter 77

Chapter 78

Chapter 79

Chapter 80

Chapter 81

Chapter 82

Chapter 83

Chapter 84

Chapter 85

Chapter 86

Chapter 87

Chapter 88

Chapter 89

Part VI: The Real Estate of Edmund Leary 1997–2000

Chapter 90

Chapter 91

Chapter 92

Chapter 93

Chapter 94

Chapter 95

Chapter 96

Chapter 97

Chapter 98

Chapter 99

Chapter 100

Chapter 101

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

About the Publisher

His father was watching the line in the water. The boy caught a frog and stuck a hook in its stomach to see what it would look like going through. Slick guts clung to the hook, and a queasy guilt grabbed him. He tried to sound innocent when he asked if you could fish with frogs. His father glanced over, flared his nostrils, and shook the teeming coffee can at him. Worms spilled out and wriggled away. He told him he’d done an evil thing and that his youth was no excuse for his cruelty. He made him remove the hook and hold the twitching creature until it died. Then he passed him the bait knife and had him dig a little grave. He spoke with a terrifying lack of familiarity, as if they were simply two people on earth now and an invisible tether between them had been severed.

When he was done burying the frog, the boy took his time patting down the dirt, to avoid looking up. His father told him to think awhile about what he’d done and walked off. The boy crouched listening to the receding footsteps as tears came on and the loamy smell of rotting leaves invaded his nose. He stood and looked at the river. Dusk stole quickly through the valley. After a while, he understood he’d been there longer than his father had intended, but he couldn’t bring himself to head to the car, because he feared that when he got there he’d see that his father no longer recognized him as his own. He couldn’t imagine anything worse than that, so he tossed rocks into the river and waited for his father to come get him. When one of his throws gave none of the splashing sound he’d gotten used to hearing, and a loud croak rose up suddenly behind him, he ran, spooked, to find his father leaning against the hood with a foot up on the fender, looking as if he would’ve waited all night for him, now adjusting his cap and opening the door to drive them home. He wasn’t lost to him yet.

Part I

1

Instead of going to the priest, the men who gathered at Doherty’s Bar after work went to Eileen Tumulty’s father. Eileen was there to see it for herself, even though she was only in the fourth grade. When her father finished his delivery route, around four thirty, he picked her up at step dancing and walked her over to the bar. Practice went until six, but Eileen never minded leaving the rectory basement early. Mr. Hurley was always yelling at her to get the timing right or to keep her arms flush at her sides. Eileen was too lanky for the compact movements of a dance that evolved, according to Mr. Hurley, to disguise itself as standing still when the police passed by. She wanted to learn the jitterbug or Lindy Hop, anything she could throw her restless limbs into with abandon, but her mother signed her up for Irish dancing instead.

Her mother hadn’t let go of Ireland entirely. She wasn’t a citizen yet. Her father liked to tout that he’d applied for his citizenship on the first day he was eligible to. The framed Certificate of Citizenship, dated May 3, 1938, hung in the living room across from a watercolor painting of St. Patrick banishing the snakes, the only artwork in the apartment unless you counted the carved-wood Celtic cross in the kitchen. The little photo in the certificate bore an embossed seal, a tidy signature, and a face with an implacably fierce expression. Eileen looked into it for answers, but the tight-lipped younger version of her father never gave anything up.

When Eileen’s father filled the doorway with his body, holding his Stetson hat in front of him like a shield against small talk, Mr. Hurley stopped barking, and not just at Eileen. Men were always quieting down around her father. The recording played on and the girls finished the slip jig they were running. The fiddle music was lovely when Eileen didn’t have to worry about keeping her unruly body in line. At the end of the tune, Mr. Hurley didn’t waste time giving Eileen permission to leave. He just looked at the floor while she gathered her things. She was in such a hurry to get out of there and begin the wordless walk that she waited until she got to the street to change her shoes.

When they reached the block the bar was on, Eileen ran ahead to see if she could catch one of the men sitting on her father’s stool, which she’d never seen anyone else occupy, but all she found was them gathered in a half circle around it, as if anticipation of his presence had drawn them near.

The place was smoky and she was the only kid there, but she got to watch her father hold court. Before five, the patrons were laborers like him who drank their beers deliberately, contented in their exhaustion, well-being hanging about them like a mist. After five, the office workers drifted in, clicking their coins on the crowded bar as they waited to be served. They gulped their beers and signaled for another immediately, gripping the railing with two hands and leaning in to hurry the drink along. They watched her father as much as they did the bartender.

She sat at one of the creaky tables up front, in her pleated skirt and collared blouse, doing her homework but also training an ear on her father’s conversations. She didn’t have to strain to hear what they told him, because they felt no need to whisper, even when she was only a few feet away. There was something clarifying in her father’s authority; it absolved other men of embarrassment.

“It’s driving me nuts,” his friend Tom said, fumbling to speak. “I can’t sleep.”

“Out with it.”

“I stepped out on Sheila.”

Her father leaned in closer, his eyes pinning Tom to the barstool.

“How many times?”

“Just the once.”

“Don’t lie to me.”

“The second time I was too nervous to bring it off.”

“That’s twice, then.”

“It is.”

The bartender swept past to check the level of their drinks, slapped the bar towel over his shoulder, and moved along. Her father glanced at her and she pushed her pencil harder into her workbook, breaking off the point.

“Who’s the floozy?”

“A girl at the bank.”

“You’ll tell her the idiocy is over.”

“I will, Mike.”

“Are you going to be a goddamned idiot again? Tell me now.”

“No.”

A man came through the door, and her father and Tom nodded at him. A draft followed him in, chilling her bare legs and carrying the smell of spilled beer and floor cleaner to her.

“Reach into your pocket,” her father said. “Every penny you have stashed. Buy Sheila something nice.”

“Yes, that’s the thing. That’s the thing.”

“Every last penny.”

“I won’t hold out.”

“Swear before God that that’s the end of it.”

“I swear, Mike. I solemnly swear.”

“Don’t let me hear about you gallivanting around.”

“Those days are over.”

“And don’t go and do some fool thing like tell that poor woman what you’ve done. It’s enough for her to put up with you without knowing this.”

“Yes,” Tom said. “Yes.”

“You’re a damned fool.”

“I am.”

“That’s the last we’ll speak of it. Get us a couple of drinks.”

They laughed at everything he said, unless he was being serious, and then they put on grave faces. They held forth on the topic of his virtues as though he weren’t standing right there. Half of them he’d gotten jobs for off the boat—at Schaefer, at Macy’s, behind the bar, as supers or handymen.

Everybody called him Big Mike. He was reputed to be immune to pain. He had shoulders so broad that even in shirtsleeves he looked like he was wearing a suit jacket. His fists were the size of babies’ heads, and in the trunk he resembled one of the kegs of beer he carried in the crook of each elbow. He put no effort into his physique apart from his labor, and he wasn’t muscle-bound, just country strong. If you caught him in a moment of repose, he seemed to shrink to normal proportions. If you had something to hide, he grew before your eyes.

She wasn’t too young to understand that the ones who pleased him were the rare ones who didn’t drain the frothy brew of his myth in a quick quaff, but nosed around the brine of his humanity awhile, giving it skeptical sniffs.

She was only nine, but she’d figured a few things out. She knew why her father didn’t just swing by step dancing on the way home for dinner. To do so would have meant depriving the men in suits who arrived back from Manhattan toward the end of the hour of the little time he gave them every day. They loosened their ties around him, took their jackets off, huddled close, and started talking. He would’ve had to leave the bar by five thirty instead of a quarter to six, and the extra minutes made all the difference. She understood that it wasn’t only enjoyment for him, that part of what he was doing was making himself available to his men, and that his duty to her mother was just as important.

The three of them ate dinner together every night. Her mother served the meal promptly at six after spending the day cleaning bathrooms and offices at the Bulova plant. She was never in the mood for excuses. Eileen’s father checked his watch the whole way home and picked up the pace as they neared the building. Sometimes Eileen couldn’t keep up and he carried her in the final stretch. Sometimes she walked slowly on purpose in order to be borne in his arms.

One balmy evening in June, a week before her fourth-grade year ended, Eileen and her father came home to find the plates set out and the door to the bedroom closed. Her father tapped at his watch with a betrayed look, wound it, and set it to the clock above the sink, which said six twenty. Eileen had never seen him so upset. She could tell it was about something more than being late, something between her parents that she had no insight into. She was angry at her mother for adhering so rigidly to her rule, but her father didn’t seem to share that anger. He ate slowly, silently, refilling her glass when he rose to fill his own and ladling out more carrots for her from the pot on the stovetop. Then he put his coat on and went back out. Eileen went to the door of the bedroom but didn’t open it. She listened and heard nothing. She went to Mr. Kehoe’s door, but there was silence there too. She felt a sudden terror at the thought of having been abandoned. She wanted to bang on both doors and bring them out, but she knew enough not to go near her mother just then. To calm herself, she cleaned the stovetop and counters, leaving no crumbs or smudges, no evidence that her mother had cooked in the first place. She tried to imagine what it would feel like to have always been alone. She decided that being alone to begin with would be easier than being left alone. Everything would be easier than that.

She eavesdropped on her father at the bar because he didn’t talk much at home. When he did, it was to lay out basic principles as he speared a piece of meat. “A man should never go without something he wants just because he doesn’t want to work for it.” “Everyone should have a second job.” “Money is made to be spent.” (On this last point he was firm; he had no patience for American-born people with no cash in their pocket to spring for a round.)

As for his second job, it was tending bar, at Doherty’s, at Hartnett’s, at Leitrim Castle—a night a week at each. Whenever Big Mike Tumulty was the one pulling the taps and filling the tumblers, the bar filled up to the point of hazard and made tons of money, as though he were a touring thespian giving limited-run performances. Schaefer didn’t suffer either; everyone knew he was a Schaefer man. He worked at keeping the brogue her mother worked to lose; it was professionally useful.

If Eileen scrubbed up the courage to ask about her roots, he silenced her with a wave of the hand. “I’m an American,” he said, as if it settled the question, and in a sense it did.

By the time Eileen was born, in November of 1941, some traces remained of the sylvan scenes suggested in her neighborhood’s name, but the balance of Woodside’s verdancy belonged to the cemeteries that bordered it. The natural order was inverted there, the asphalt, clapboard, and brick breathing with life and the dead holding sway over the grass.

Her father came from twelve and her mother from thirteen, but Eileen had no brothers or sisters. In a four-story building set among houses planted in close rows by the river of the elevated 7 train, the three of them slept in twin beds in a room that resembled an army barracks. The other bedroom housed a lodger, Henry Kehoe, who slept like a king in exchange for offsetting some of the monthly expenses. Mr. Kehoe ate his meals elsewhere, and when he was home he sat in his room with the door closed, playing the clarinet quietly enough that Eileen had to press an ear to the door to hear it. She only saw him when he came and went or used the bathroom. It might have been strange to suffer his spectral presence if she’d ever known anything else, but as it was, it comforted her to know he was behind that door, especially on nights her father came home after drinking whiskey.

Her father didn’t always drink. Nights he tended bar, he didn’t touch a drop, and every Lent he gave it up, to prove he could—except, of course, for St. Patrick’s Day and the days bookending it.

Nights her father tended bar, Eileen and her mother turned in early and slept soundly. Nights he didn’t, though, her mother kept her up later, the two of them giving a going-over to all the little extras—the good silver, the figurines, the chandelier crystals, the picture frames. Whatever chaos might ensue upon her father’s arrival, there prevailed beforehand a palpable excitement, as if they were throwing a party for a single guest. When there was nothing left to clean or polish, her mother sent her to bed and waited on the couch. Eileen kept the bedroom door cracked.

Her father was fine when he drank beer. He hung his hat and slid his coat down deliberately onto the hook in the wall. Then he slumped on the couch like a big bear on a leash, soft and grumbling, his pipe firmly in the grip of his teeth. She could hear her mother speaking quietly to him about household matters; he would nod and press the splayed fingers of his hands together, making a steeple and collapsing it.

Some nights he even walked in dancing and made her mother laugh despite her intention to ignore him. He lifted her up from the couch and led her around the room in a slow box step. He had a terrible charisma; she wasn’t immune to it.

When he drank whiskey, though, which was mostly on paydays, the leash came off. He slammed his coat on the vestibule table and stalked the place looking for things to throw, as if the accumulated pressure of expectations at the bar could only be driven off by physical acts. It was well known what a great quantity of whiskey her father could drink without losing his composure—she’d heard the men brag about it at Doherty’s—and one night, in response to her mother’s frank and defeated question, he explained that when he was set up with a challenge, a string of rounds, he refused to disappoint the men’s faith in him, even if he had to exhaust himself concentrating on keeping his back stiff and his words sharp and clear. Everyone needed something to believe in.

He didn’t throw anything at her mother, and he only threw what didn’t break: couch pillows, books. Her mother went silent and still until he was done. If he saw Eileen peeking at him through the sliver in the bedroom door, he stopped abruptly, like an actor who’d forgotten his line, and went into the bathroom. Her mother slid into bed. In the morning, he glowered over a cup of tea, blinking his eyes slowly like a lizard.

Sometimes Eileen could hear the Gradys or the Longs fighting. She found succor in the sound of that anger; it meant her family wasn’t the only troubled one in the building. Her parents shared moments of dark communion over it too, raising brows at each other across the kitchen table or exchanging wan smiles when the voices started up.

Once, over dinner, her father gestured toward Mr. Kehoe’s room. “We won’t have him here forever,” he said to her mother. As Eileen was struck by sadness at the thought of life without Mr. Kehoe, her father added, “Lord willing.”

No matter how often she strained to hear Mr. Kehoe through the walls, the only sounds were the squeaks of bedsprings, the low scratching of a pen when he sat at the little desk, or the quiet rasp of the clarinet.

They were at the dinner table when her mother stood and left the room in a hurry. Her father followed, pulling the bedroom door closed behind him. Their voices were hushed, but Eileen could hear the straining energy in them. She inched closer.

“I’ll get it back.”

“You’re a damned idiot.”

“I’ll make it right.”

“How? ‘Big Mike doesn’t borrow a penny from any man,’” she sneered.

“There’ll be a way.”

“How could you let it get so out of hand?”

“You think I want my wife and daughter living in this place?”

“Oh, that’s just grand. It’s our fault now, is it?”

“I’m not saying that.”

In the living room, the wind shifted the bedroom door against Eileen’s hands, making her heart beat faster.

“You love the horses and numbers,” her mother said. “Don’t make it into something it wasn’t.”

“It was in the back of my mind,” her father said. “I know you don’t want to be here.”

“I once believed you could wind up being mayor of New York,” her mother said. “But you’re satisfied being mayor of Doherty’s. Not even owner of Doherty’s. Mayor of Doherty’s.” She paused. “I should never have taken that damn thing off my finger.”

“I’ll get it back. I promise.”

“You won’t, and you know it.” Her mother had been stifling her shouts, practically hissing, but now she sounded merely sad. “You chip away and chip away. One day there won’t be anything left.”

“That’s enough now,” her father said, and in the silence that followed Eileen pictured them standing in the mysterious knowledge that passed between them, like two stone figures whose hearts she would never fathom.

The next time she was alone in the house, she went to the bureau drawer where her mother had stashed her engagement ring for safekeeping ever since the time she’d almost lost it down the drain while doing dishes. From time to time, Eileen had observed her opening the box. She’d thought her mother had been letting its facets catch the light for a spell, but now that she saw the empty space where the box had been, she realized her mother had been making sure it was still there.

A week before her tenth birthday, Eileen walked in with her father and saw that her mother wasn’t in the kitchen. She wasn’t in the bedroom either, or the bathroom, and she hadn’t left a note.

Her father heated up a can of beans, fried some bacon, and put out a few slices of bread.

Her mother came home while they were eating. “Congratulate me,” she said as she hung up her coat.

Her father waited until he finished chewing. “For what?”

Her mother slapped some papers on the table and looked at him intently in that way she sometimes did when she was trying to get a rise out of him. He bit another piece of bacon and picked the papers up as he worked the meat in his jaw. His brow furrowed as he read. Then he put them down.

“How could you do this?” he asked quietly. “How could you let it not be me?”

If Eileen didn’t know better, she would have said he sounded hurt, but nothing on earth was capable of hurting her father.

Her mother looked almost disappointed not to be yelled at. She gathered the papers and went into the bedroom. A few minutes later, her father took his hat off the hook and left.

Eileen went in and sat on her own bed. Her mother was at the window, smoking.

“What happened? I don’t understand.”

“Those are naturalization papers.” Her mother pointed to the dresser. “Go ahead, take a look.” Eileen walked over and picked them up. “As of today, I’m a citizen of the United States. Congratulate me.”

“Congratulations,” Eileen said.

Her mother produced a sad little grin between drags. “I started this months ago,” she said. “I didn’t tell your father. I was going to surprise him, bring him along. It would have meant something to him to be my sponsor at the swearing in. Then I decided to hurt him. I brought my cousin Danny Glasheen instead.”

Eileen nodded; there was Danny’s name. The papers looked like the kind that would be kept in a file for hundreds of years, for as long as civilization lasted.

“Now I wish I could take it back.” Her mother gave a rueful laugh. “Your father is a creature of great ceremony.”

Eileen wasn’t sure what her mother meant, but she thought it had to do with the way it mattered to her father to carry even little things out the right way. She’d seen it herself: the way he took the elbow of a man who’d had too much to drink and leaned him into the bar to keep him on his feet without his noticing he was being aided; the way he never knocked a beer glass over or spilled a drop of whiskey; the way he kept his hair combed neat, no strand out of place. She’d watched him carry the casket at a few funerals. He made it seem as if keeping one’s eyes forward, one’s posture straight, and one’s pace steady while bearing a dead man down the steps of a church as a bagpiper played was the most crucial task in the world. It was part of why men felt so strongly about him. It must have been part of why her mother did too.

“Don’t ever love anyone,” her mother said, picking the papers up and sliding them into the bureau drawer she’d kept her ring in. “All you’ll do is break your own heart.”