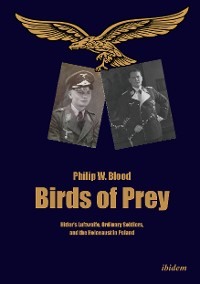

Loe raamatut: «Birds of Prey»

ibidem-Press, Stuttgart

In Memory of

Professor E. Richard Holmes (1946–2011)

Soldier, scholar, gentleman.

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements

List of Tables

List of Diagrams

List of Maps

List of Images

Abbreviations and Glossary

1942

Excursions in Microhistory

An Aide-Mémoire: Reading Maps Like German soldiers

1. The Ogre of Rominten

2. The Conquest of Wilderness

3. Grossdeutschland

4. Bandenbekämpfung in the ‘Home Forces Area’

5. The Białowieźa Partisans

6. Population Engineering

7. Judenjagd

8. German Soldiers and Bandenbekämpfung

9. 1943

10. Göring’s Hunter Killers

11. Bandenjagd

12. 1944: Retreat

Conclusion: Memories of a Never Happened History

Epilogue

Appendix 1: German Ranks

Appendix 2: Luftwaffe Soldiers

Bibliography

About the Author

Acknowledgements

‘This is the smoking gun of all your research.’

Professor Richard Holmes, 18 February 2001.

On 3 February 2020, I met Heinrich Schreiber for the last time. My friend and neighbour was 97 and his faculties were rapidly decining through the lethal onset of dementia. In 1943, he was called up to the German Army, severely wounded at Smolensk in Soviet Russia, and was awarded the Allgemeines Sturmabzeichen (general assault badge). The memory of the badge remained his foremost achievement in a lifetime of struggles faced by so many working class people born before the war. Since 1970, I was fortunate to meet many Second World War veterans but Heinrich had taught me aspects of military culture barely studied by military historians. He discussed combat reports, the importance of signals and short-hand report writing. He could read and explain the meaning of reports and would explain the limits of his experience through his platoon, company and battalion. His division(s) had long since disappeared from memory. His only observation about the reports in this book, ‘so the Luftwaffe were also at it’. Perhaps a veiled reference to Nazi crimes, perhaps the universality of the military culture, or perhaps the memories of the east. From talking with Heinrich over ten years, I learned that working class German men went to war not much differently from those of other countries. The hardships of life continued after Hitler came to power, his family lost their farm tenancy when the rents were raised beyond their meagre means. Heinrich began work as a shoemaker, but his apprenticeship was interrupted by the war. After the war he became a stonemason. He passed away a month later, finally drawing to a close my contact with the war generation in Britain and Germany.

There were several key persons behind the completion of this book. The late Professor Brigadier E. Richard Holmes (1947–2011) was my doctoral supervisor. Our relationship began as professor-student, but then he turned mentor, and eventually became friends. During the research for my PhD, Richard saw the Luftwaffe records in this book and after reading my thesis summary said it was ‘the smoking-gun of my Bandenbekämpfung research.’ He recommended Birds of Prey should be a specific book and include the synthesis between the hunt and the military training. Richard’s colleague, Professor Chris Bellamy (Greenwich) was the second supervisor and he agreed with Richard that a chapter in the thesis should form the foundation for a subsequent book. Chris encouraged more research of the underlying violence between the Soviet partisans and the Germans to explain why Bandenbekämpfung was not anti-partisan warfare. Scholarly technicalities aside, studying under Richard and Chris was a dynamic experience. A special mention should also be made for Steph Muir, Richard’s assistant who was a constant pillar of support to all of us.

Beyond mentoring and friendship is another level of scholarly relationship that defies definition. During a meeting of the Anglo-German seminar group (1997–98), I met Dr. Nicholas Terry (University of Exeter). He was then a PhD candidate researching the German Army and we became immediate friends. Our friendship has spanned from the Goldhagen-Browning debates, the ‘clean Wehrmacht’ scandals, several conferences with publications and on into the Twenty-First Century. In 1998 we first discussed the content in the Luftwaffe files. He recommended presenting a paper at the Wiener Library event. While drafting my PhD thesis, Nick suggested signposting the role of the Luftwaffe in Bandenbekämpfung. Since 2006, Nick has been the constant advisor/mentor for this book and his was on his advice I decided upon the microhistory format.

There have also been a number of specialist advisors who have assisted me. Dr. Declan O’Reilly (London-KCL) has been a scholary conciliare and tough critic since 1998. My dear friend Dr Joe White, from the USHMM, was very supportive of my research. Following a visit to the UK, Joe recommended an article for the Holocaust and Genocide Studies Journal and introduced me to Dr. Michael Gelb (USHMM). Thanks to Michael’s editing the article was published in 2010. Joe passed away in 2016 and as did Dr Geoffry Megaggee four years later. Fond recollections of those ‘brown bag’ lunches and lively discussions about our research. During a visit to the BA-MA archive in Freiburg in 1998, I met and discussed the life of ordinary German soldiers with Professor Jochen Böhler (Jena University). This changed my perception of ordinary German soldiers. In 2009, Dr. Tomasz Samojlik (Mammal Research Institute, Białowieźa) kindly shared his ideas on the Polish history of the forest. Tomasz very kindly supplied the forest maps that led to the digitization process central to this book. At a critical time, Professor Beatrice Heusser (University of Glasgow) offered important supervisory advice on taking the research to the final manuscript. My life partner Bettina Wunderling BSc. was important to the research by formulating the application of GIS in the cartographical research. In the latter stages of completing this manuscript, Dr. Matthew Ford (University of Sussex) gave up considerable time on modern counterinsurgency, military innovation and concepts of education, including training. He also directly edited several chapters. I would like to also thank Dr. Olaf Bachmann (King’s College London) and Jake Halliday (Buckingham), for reading and commenting on the manuscript.

Since 1998 several academic institutions have been crucial to this project. Their help and support was particularly welcome since this project was self-funded. The Bundesarchiv (Germany), National Archives (London), Mammal Research Institute (Poland), National Archives and Records Administration (USA) provided unhindered access to records and advice. The RWTH-Bibliothek (Aachen), Staatsbibliothek (Aachen) and British Library (London) granted full access to holdings and inter-library loans. Germany has retained many of the traditional ideas open access learning for all and this deserves special mention in this book. The Internet Archive (Washington DC) granted unfettered access to all digitised sources, which was articularly helpful for older books outside the e-book systems. ESRI provided advice and guideance in the application of GIS software in 2010–12.

In fourteen years, many people have been involved in this book, for which I am eternally grateful: Special thanks are reserved for: Mike Buckley MA, Michael Birklein MA, Dr. Roger Cirillo (AUSA), Dr. Halik Kochanski, Dr. Bernd Lemke (Potsdam), Professor James Corum (Salford), Professor Dennis Showalter (†), Jörg Muth (Baltic Defence College), Professor Jesse Kauffmann (Eastern Michigan), Michael Birklein (RWTH-Aachen), Tomasz Frydel (Ottowa), Michael D. Miller, and Valerie Lange and Malisa Mahler from ibidem publishing house. In 2020, I joined the Twitter community and have received very supportive advice and guidance.

Finally, to family and friends. Whereas in a second book family and friends become part of a list, unusual to this story was the extended period of serious illness launched them into a strategic role. My parents, Pamela and Peter Blood, have always supported my work and career. Also to my relatives Jan, Lauren, Colin and Dr. Alexander Ford. My dearest friend for more than forty years, Manny Phelps passed away in 2015. After major surgery and disability, he devised the means to restore my writing that led to this book. We shared an interest in the Luftwaffe and I would hope this meets with his high standards of accuracy and detail. Manny’s family of Maria, Ricky, Danielle and Nicole remain precious to me. Dr. Barry Rosenthal (Baltimore) is a dear friend and supported this project with advanced computers. Harry Wise (London taxi driver) and Bradley J. Hodgson (gunsmith) spent hours explaining gun-making, drive-hunting, and that special relationship between rifles and marksmanship. All my friends mentioned in my first book were also part of the progress to this. Thank you to German doctors and medical staff who have worked incredibly hard in my interest over the last fourteen years.

List of Tables

Table 1: Bach-Zelewski’s travel itinerary

Table 2: fluctuations in manpower levels

Table 3: LWSB, death by shooting, 14 August 1942

Table 4: LWSB, death by hanging, 9 September 1942

Table 5: LWSB, hanging 22 September 1942

Table 6: LWSB, death by hanging, October 1942

Table 7: Forest communities and the results of deportation

Table 8: Settled out of the forest.

Table 9: LWSB, death by hanging, 22 December 1942

Table 10: executions through hanging, 20 November 1942

Table 11: LWSB, death by hanging, February 1943

Table 12: LWSB death sentences on 24 February 1943

Table 13: final deployment of the LWSB on 5 March 1943

Table 14: Herbst’s amended body count

Table 15: JSKB expenditures—fuel and ammunition

Table 16: JSKB roster, 6 March 1943

Table 17: JSKB muster March–October 1943

Table 18: LW Signals Regiment 1 schedule

Table 19: JSKB muster October 1943 to August 1944

List of Diagrams

Diagram 1: Reichsforstamt organisation and the Jagdamt (1936).

Diagram 2: the four categories of reported incidents

Diagram 3: age range of sixth company officers and NCOs

Diagram 4: age profile of sixth compan

Diagram 5: Original branch of Service with transfers

Diagram 6: Personnel assigned from Flak regiments

Diagram 7: LWSB/JSKB casualties

Diagram 8: cause of fatal wounds

List of Maps

Map 1: Poland divided, Nazi occupation zones in Poland, Soviet Russia and the Ukraine.

Map 2: Bezirk Bialystok circa 1944.

Digital Map 3: Luftwaffen Karte des Urwaldes Bialowies.

GIS Map 4: Police Battalion 322—the village deportations 25 July–15 August 1941

GIS Map 5: the Kobylinski deployment

GIS Map 6: LWSB strongpoints—6 August 1942

GIS Map 7: before the arrival of Fourth Company—10 October 1942

GIS Map 8: after the arrival of Fourth Company—2 November 1942

GIS Map 9: the arrival of Fifth and Sixth companies—19 November 1942

GIS Map 10: the positions of Soviet partisans killed by LWSB

GIS Map 11: deportations—comparison of summer 1941 and autumn/winter 1942

GIS Map 12: the total distribution of hideouts discovered by the LWSB

GIS Map 13: locations of Jews killed by the LWSB

GIS Map 14: The Final Deployment—5 March 1943

GIS Map 15: JSKB deployment—6 March 1943

GIS Map 16: Luftwaffe signals network and the German frontier 1943–1944

GIS Map 17: JSKB hunting patrols—March to October 1943

GIS Map 18: destruction of Jagdkommando Marteck

GIS Map 19: the Nönning Judenjagd

GIS Map 20: Unternehmen Vatertag—3 June 1943

GIS Map 21: JSKB second phase north/south final deployment

GIS Map 22: Plan for Unternehmen Paul, 28–29 May 1944

List of Images

Image 1: left to right, Oberforstmeister Walter Frevert Rominten, Göring in his capacity as Reichsjägermeister and Oberstjägermeister Ulrich Scherping.

Image 2: Senior Luftwaffe and state foresters in the lounge area in Rominten. A painting of a European Bison is hung on the far wall.

Image 3: European Bison in Białowieźa.

Image 4: Reichsmarschall Göring, Lw.Generalmajor Adolf Galland, Lw.Generaloberst Bruno Loerzer and Reichminister Albert Speer, August 1943.

Image 5: Bernd von Brauchitsch in his cell in Nuremberg prison 1946.

Image 6: Preparation for a diplomatic function at Rominten. Note the Nordic runes on the picture rail under the ceiling.

Image 7: Sites of memory—Located beside the railway in Zabłotczyzna (2 miles from Narewka), the memorial refers to approximately 500 Jews killed on 5 August 1941. The German records show 282 Jewish men were killed at that place on 15 August 1941.

Image 8: A German Army Ortskommandtur: issuing daily notices and labour assignments.

Image 9: Captured Soviet partisans after interrogation but before execution.

Image 10: Armed trusty and Nazi Collaborator.

Image 11: Białowieźa forest—partisan memorial in the conservation area.

Image 12: Civilian deportations and allocation to work or forced labour duties.

Image 13: Villages destroyed and cattle taken under the Nazi food plan.

Image 14: Luftwaffe troops in company order.

Image 15: Luftwaffe troops in action in the forest.

Image 16: Wounded Luftwaffe troops recovering in a military hospital.

Image 17: Typical strongpoint construction in wood.

Image 18: Reichsjägermeister Göring and his prize— Matador —the ceremony for the dead stag—22 September1942

Image 19: The signals was regarded as the advanced branch of the Luftwaffe. Recruits received a full training schedule equivalent to apprenticeships in industry.

Image 20: Sites of memory—Soviet military cemetery located within Hajnówka town. Engraving reads: Hero of the Soviet Union, Guards Junior Lieutenant Aleksii Vasilevich Florenko. Born 6 February 1922. He died in the fight to liberate Hajnówka region 25 July 1944.

Image 21: Sites of memory—located in the centre of Białowieźa town, the memorial stands on the site where public executions were conducted during the Nazi occupation.

Image 22: Sites of memory—located within the Narewka town limits, the Jewish cemetery survived the Nazi occupation.

Image 23: Sites of memory—located nearby Białowieźa town. They are memorials to the mass killings and destroyed villages in 1942. They stand in the grounds of the former German military cemetery, first constructed during the Imperial German Army occupation in 1915-18.

Image 24: In his position as General of Fighters, Adolf Galland approved and endorsed this anti-Semitic trope in comic form. The connections between hunting, the Luftwaffe and training had reached complete integration.

Image 25: Sites of memory—German dead relocated from Białowieźa cemetery. The search for Siegfried Adams burial place marked by my index finger.

Image 26: Heimatkriegsgebiet - Luftwaffe troops in training building small unit cohesion.

Image 27: Dress uniforms and other duties.

Image 28: The Luftwaffe troops assigned to the LWSB/JSKB were generally young and often reassigned from non-combat branches.

Abbreviations and Glossary

AA: Arolsen Archives, located at: https://collections.arolsen-archives.org/en/ search/

BArch: Bundesarchiv, including BA: Berlin (Lichterfelde); BAK: (Koblenz); BA MA: Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv, (Freiburg); BA-ZNS: Bundesarchiv-Zentralnachweisstelle (formerly in Aachen).

CMH: United States Army Center of Military History.

CP: command post.

DDSt: Deutsche Dienststelle (WASt), former Wehrmacht personnel archive.

FJK/FSK: Feldjägerkorps or Feldschützkorps, Nazi paramilitary forestry formations.

FMS: US Army Historical Branch, Foreign Military Studies (German army).

FSKAB: Forstschutzkommando-Abteilung Bialowies, the paramilitary forestry formations assigned to Białowieźa.

HSSPF: Höhere SS-Polizeiführer, regional or theatre SS and Police commander.

IMT: International Military Tribunal, Nuremberg.

IWM: Imperial War Museum, (London).

Jagen: a 1 kilometre square sector, a measurent to micro-manage trees and game reserves.

JSKB: Luftwaffe Jäger Sonderbataillon Bialowies zbV. (March 1943–August 1944).

Ln. : Luftwaffenachrichten, Luftwaffe signals.

Luftwaffe: German Air Force.

Lw.: Luftwaffe abbreviated for ranks and units.

LWSB: Luftwaffe Sonderbataillon Bialowies zbV. (July 1942–March 1943).

MGFA: Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt, Bundeswehr’s military history department since changed to ZMSBw, see below.

NARA: National Archive, College Park annex, Colombia Park Maryland, USA.

NCOs: German Unteroffiziere and non-commissioned officer ranks.

OP: observation post.

ORs: other ranks, non-commissioned military personnel.

PB: police battalion.

PoW: Prisoner(s) of War.

RFA: Reichsforstamt—Nazi ministry of state forestry.

Soltys: Lithuanian, refers to the local head person of a village.

SSPF: SS-Polizeiführer, district SS and Police commander.

TNA: The National Archives, formerly the Public Records Office (PRO), London

TsAMO Bestand 500 Findbuch 12452: Deutsch-Russisches Pojekt Zur Digitalisierung Deutscher Dokumente in Archiven Der Russischen Föderation (digitised captured German records). Located online at: https://wwii.germandocsinrussia.org/de/ nodes/ 2410-findbuch-12452-oberkommando-der-luftwaffe-okl

USHMM: United States Holocaust Memorial and Museum, Washington DC, USA.

Waffen-SS: militarised Schutzstaffeln, the military expansion from Hitler’s bodyguard detachment.

YVA: Yad Vashem, The World Holocaust Remembrance Centre, located at: https://documents.yadvashem.org

zbV: zur besonderen Verwendung, special duties or special deployment.

ZMSBw: Zentrum fur Militärgeschicte und Sozialwissenschaften der Bundeswehr.

1942

In January 1942 a popular German hunt magazine published a remarkable story about Luftwaffe Colonel Adolf Galland. During the German army’s attack on Moscow, in the winter of 1941, the famous fighter ace took time out to go hunting. He was an expert hunter, like so many Luftwaffe officers, and wanted to extend his record to the forests of the east. Galland together with his adjutant set off without an armed escort into a gloomy forest just north of Dünaberg (today Daugavpils in Latvia). The forest was renowned for its game but was badly scarred by war. The Soviet Red Army had put up a spirited defence, however the Germans forced them to retreat. The Russians had abandoned their trenches leaving behind the detritus of war; discarded equipment, clothing and weapons littered the forest floor. As the two hunters strolled deeper into the forest, they disturbed a herd of Roe deer. They decided to separate, and Galland took up a position in a bush by a clearing and a stream. Very soon he observed and shot a roebuck. The single shot wounded the buck and it sprinted away. Galland set off in pursuit but stumbled into a ditch breaking through ice immersing himself and coat in sticky mud. He sloshed around in the freezing muddy water trying to break free from its suction. By luck, his hunting rifle hadn’t got wet and continued the search as he followed a blood trail. Covered in sticky wet mud, Galland trudged deeper into the gloomy forest and eventually located the buck, it was dead. An impressive trophy, ‘I am overcome with joy! I did not expect such strong antlers.’ Galland put down his rifle, took up his hunter’s blade, and began preparing the carcass.

Suddenly, and without warning, Galland faced three armed Russians. ‘We were all surprised’ he exclaimed. Galland shouted ‘sstaj’, presumably meaning stop or halt, but a Russian fired at him. He took up his rifle and fired back, ‘one of the Russians clasped his chest and collapsed.’ Galland tried to shoot again but his rifle wasn’t loaded. He struggled to pull a bullet from his coat pocket, but it was snagged in sticky mud. Unable to gauge the Russians’ intentions, Galland opted to back off. He was temporarily forced to abandon his trophy later recalling, ‘only a hunter will understand how I felt!’ After a short time, he returned for his trophy: ‘I don’t think I will ever value a set of antlers more than those for which I had to fight with considerable luck.’ Galland penned his hunting tale, ‘in my shelter while being heavily bombarded by Russian artillery during the great offensive against Moscow that promises final victory’. He pondered the shortcomings of hunting in the ‘paradise of farmers and workers’ (contemptuous Nazi brogue for the Soviet Union), and that most wildlife had fled the forests as the front lines approached. The animals that remained had been exterminated rendering minimal hunting opportunities. To conclude his tale, Galland warned his fellow hunters and foresters to seek permission before hunting in the forests of the east: ‘A number of dangerous bandits are still roaming the large forest areas between the River Memel and Lake Peipus and will do for a long time to come.’ Galland’s parting shot was to assume his ‘report’ offered sound advice to those who recognise the value and the importance of German protective security in the east.1 Within a year, the random confrontations with partisans had turned into a major Soviet insurgency campaign.

On 1 December 1942, Adolf Hitler faced a military calamity. A week before, the Soviet Red Army had encircled Stalingrad, isolating the Sixth Army from adequate supplies or relief. Since the beginning of 1942, a raging Soviet insurgency had undermined all efforts to pacify the German occupied territories.2 The increased Soviet partisan penetrations had become a priority discussion for that evening’s military conference. Hitler introduced the Draft of Official Regulations for the struggle against banditry and explained:

The goal must be to destroy the bandits and restore peace and order. Otherwise, we will end up in the same situation that we had once in our domestic affairs, with the so-called self-defence clause. This clause led to the situation that no policeman or soldier actually dared to use his gun in Germany.3

The progress of Hitler’s policy, from proposal to directive to doctrine to dogma, had followed a predictable path. In late 1941, Hitler invited Heinrich Himmler, chief of the SS and German police, to find a solution. In June 1942, Himmler initiated a planning process with particular instructions to his senior SS-Police officers. He demanded their proposals must include the vilification of the ‘partisan’ as an illegal ‘bandit’. Then from the proposals Hitler issued: Führer Directive No. 46, Richtlinien für die verstärkte Bekämpfung des Bandenunwesens im Osten (Instructions for Intensified Action against Banditry in the East) in August 1942.4 The policy was tried and tested under SS auspices, and in parallel, the chief of staff of the Army issued general instructions to form Jagdkommando (hunting-squads) to combat the ‘bandit bands’. All rear area forces were directed to exterminate the ‘bandits’ with the utmost ferocity. Also, cruel sanctions were imposed on civilians for assisting the bands, including execution or slave labour, their homes burned, and crops destroyed. The Bandenbekämpfung doctrine was officially introduced on 27 November but the doctrine’s architecture and language were already institutionalised by the summer of 1942.5

The Luftwaffe’s participation in Bandenbekämpfung was critical to security operations on the Eastern Front. In April 1942, the Luftwaffe committed ground forces and support units. At that stage, German security and counterinsurgency still conformed to the army’s regulations and tactical doctrines. From August, the SS became the guardians of Bandenbekämpfung dogma within all the Third Reich’s civil-military authorities, while the Wehrmacht gradually filtered the terminology into reports. On 31 December, the Luftwaffen Kommando Ost issued a report on the entire period since April. The report opened:

The increasing activities of the bandits since 1941/42 in the rear of Army Group Centre, presents a serious danger to the supply and the conduct of the war by the army and air force, or exploit or colonize local economies. Although large-scale operations and smaller actions to combat the bandits were conducted successfully by the security units, the bandit activity increased, especially in the frontline or area of the frontlines. This was aggravated by Red Army Frontlaufer, or stragglers, often supplied by the Red Air Force, and the bands’ press-ganged local people and trained them.6

The Soviets had organised raiding parties or bands of 200–400 men with specialists—scouts, messengers and saboteurs. These bands had constant and reliable communications with the Soviet Union, through signals, messengers and aircraft, which enabled re-supplies and reinforcements. These Red Army bands were properly organised and well armed, and ranged deep into occupied territory.7 The local populations were either directly assisting them or supplying food. The Germans were also disturbed that the band’s weapons were good quality and included mortars, anti-tank guns, and field artillery, and warned against underestimating the ‘bandits’.8

In response to the partisan threat the Luftwaffe had been forced to take ‘special measures’ to protect the airfields. Luftwaffen Kommando Ost recognised that the few security troops could not stem the advance of the bands. In response, on 24 April, Göring granted permission for the formation of Lw.Infantry Regiment Moskau from surplus manpower from tactical formations, building and construction units, as well as signallers and staff cadres. Training was shortened and the regiment was deployed in June. For a period, the regiment was the only available infantry in the entire area of Luftwaffen Kommando Ost and were committed to security tasks in sectors with high concentrations of partisan infiltrations. They were also briefly engaged in the frontline when circumstances demanded their commitment to conventional warfare. The ‘bandits’, according to the Luftwaffe’s colourful use of the emerging Lingua Franca, were committed to widespread Bandenanschlägen (acts of terror), with attacks on railways roads, stores, bridges, dairies, landed estates, warehouses, and kidnapping mayors (collaborators). The insurgency increased into Autumn 1942, which led the Germans to take more radical measures. The bands posed a serious threat to the occupation, the supply of the front and military communications. The Luftwaffe had facilitated a general replenishment of all its units, with increased training and reinforcements. The only limitations to the increases were inadequate shelters for the troops with the onset of winter. The army and Luftwaffe imposed similar mission targets of Befriedungsräume (entirely pacified area)—achieved through pacification, cleansing, and destruction. The Luftwaffen Kommando Ost report included a Butcher’s Bill: body counts with destroyed villages and lists of captured booty. The list of destruction included: 19 ‘bandit-camps’, 88 enemy villages, 140 bunkers destroyed, 1,284 partisans shot after capture, and lists of equipment. Subsequent research by James Corum uncovered the Lw. Infantry Regiment Moskau was responsible for the destruction of 5,000 houses and killed seventy-six hostages.9

Map 1: Poland divided, Nazi occupation zones in Poland, Soviet Russia and the Ukraine.

© J. Noakes & G.Pridham, Nazism 1919–1945 Volume 3, Foreign Policy, War and Racial Extermination, A Documentary Reader, University of Exeter Press, Exeter 1995, p. 1222, courtesy Liverpool University Press.

The report closed with a series of post-operational observations, which indicate that Göring’s lieutenants were not only experts in the application of security warfare, but were well versed in the politics of Bandenbekämpfung. The first observation concerned the local population vis-à-vis the Bandenlage (bandit situation): if the locals were peaceful, they were usually ‘happy’ to be protected by German troops; in bandenbeherrschten Gebieten (bandit-controlled areas) the locals work for the ‘bandits’; however, in the bandenverseuchten Gebieten (‘bandit’ diseased areas) the locals expected to be targeted by both sides. One comment concluded that local co-operation was necessary for the successful pacification and exploitation of an area, and it was therefore, critical to impose German rule. A second observation concerned the compromise of Nazi propaganda by security operations. It was recognised that burning villages for revenge or retribution might backfire, especially if the locals were both harmless and helpless. However, if an area was collaborating with the ‘bandits’ it was necessary to ‘cleanse with a firm hand.’ The third observation noted how the morale of the troops suffered when expected to combat the ‘bandits’ with inferior weapons. The bands were well supplied with superior and heavy weapons, and several times Luftwaffe flak artillery engaged in direct firing against heavily armed ‘bandits’. Another point mentioned the high level of mobility adopted by the ‘bandits’, which meant the Luftwaffe depended on the army’s security units to effect a mobile counter-strategy. A further observation criticised the absence of a unified command, and there had been reports of chaotic incidents. This had led to a centralisation of all Luftwaffe forces and the reorganisation of command structures. There had also been an introduction of strongpoints at important hubs along the railway lines, with Luftwaffe troops assigned to guarding junctions. A final point noted how the ‘bandits’ adopted ‘sneaky’ tactics, which required strong forces to counter and eradicate them. There was a palpable reluctance in a recommendation to conduct night-time actions and the troops to be trained to work in ‘night and fog’—the distasteful notion of resorting to ‘bandit’ tactics to counter the ‘bandits’. Operational training was acknowledged as the key to success and especially in learning to exploit the same methods as the ‘bandits’—the use of cunning, and ruthlessness.10