Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

Loe raamatut: «The Meadow: Kashmir 1995 – Where the Terror Began»

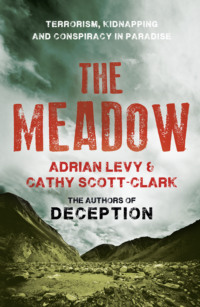

ADRIAN LEVY AND

CATHY SCOTT-CLARK

The Meadow

Terrorism, Kidnapping

and Conspiracy in Paradise

For all of the injured, the dead and the missing

The headlights filled the road. Everyone cried

out for mother and father’s love and as the

doors to the ascent opened the ballad began

again. For his disappeared love he went from

hole to hole, grave to grave, searching for the

eyes that don’t find. From gravestone to

gravestone, from cry to cry, it went through

niches, through shadows, and it went like this.

FROM RAÚL ZURITA, SONG FOR HIS DISAPPEARED LOVE, TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH BY DANIEL BORZUTZKY

(ACTION BOOKS, NOTRE DAME, INDIANA, 2010)

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

List of Illustrations

MAPS:

South Asia

Central Srinagar

Southern Kashmir and Doda District

Trekking and Pilgrimage Routes in Kashmir Valley

Anantnag District

Dramatis Personae

Abbreviations

Prologue

1. Packing

2. A Father’s Woes

3. The Meadow

4. Home

5. Kidnap

6. The Night Callers

7. Up and Down

8. Hunting Dogs

9. Deadline

10. Tikoo on the Line

11. Winning the War, Call by Call

12. The Golden Swan

13. Resolution Through Dialogue

14. Ordinary People

15. The Squad

16. The Game

17. The Goldfish Bowl

18. Chor-Chor Mausere Bhai (All Thieves are Cousins)

19. Hunting Bears

20. The Circus

Epilogue: Fill Your Arms with Lightning

Picture Section

Acknowledgements

A Note on Sources

About the Authors

Praise

By the Same Authors

Copyright

About the Publisher

ILLUSTRATIONS

1. The route to the Meadow, photographed by Hans Christian Ostrø shortly before he was kidnapped. (Marit Hesby)

2. Julie and Keith Mangan and Catherine Moseley trek towards the Meadow in early July 1995. Photo by Paul Wells. (Bob Wells)

3. Cath, Keith and Julie trek towards the Meadow. Photo by Paul Wells. (Bob Wells)

4. Setting up camp en route to the Meadow. Photo by Paul Wells. (Bob Wells)

5. Hans Christian Ostrø being made up for his kathakali dance graduation show in Sreekrishnapuram, May 1995. (Marit Hesby)

6. Ostrø on board Montana houseboat, Dal Lake, Srinagar. (Marit Hesby)

7. The Heevan Hotel in Pahalgam. (Courtesy Conveyor magazine, Srinagar)

8. The wives and girlfriends of the kidnapped men leaving the first press conference at the Welcome Hotel in Srinagar on 13 July 1995. (Agency photo)

9. Rajinder Tikoo, Inspector General of Crime Branch at the time of the kidnappings. (Undated photo, courtesy Kashmir Times)

10. Members of the al Faran kidnap party. (Courtesy Maqbool Sahil)

11. One of the first hostage photographs, taken by al Faran outside the herders’ hut from which John Childs had escaped in the early hours of 8 July. (Agency photo)

12. Lt. General (retired) D.D. Saklani, Security Advisor to the Governor of Kashmir. (AP)

13. John Childs reunited with his daughters on 15 July 1995. (Agency photo)

14. Childs shortly after his rescue. (Agency photo)

15. A picture of the hostages and their captors that was delivered to the Srinagar Press Enclave on 14 July 1995, shortly before the first deadline expired. (Marit Hesby)

16. Hostages photographed inside an unidentified herders’ hut, probably in the Warwan Valley. (Marit Hesby)

17. The Warwan Valley, where the hostages were held for eleven weeks. (Authors’ archive)

18. Sukhnoi village. (Authors’ archive)

19. Indian security forces question shepherds about the whereabouts of the hostages. (AP Photo/Qaiser Misra)

20. Don Hutchings, supposedly injured following a botched Indian security force operation. (Authors’ archive)

21. Hans Christian Ostrø’s corpse at Anantnag police station in south Kashmir. (Marit Hesby)

22. The hostages soon after they arrived in the Warwan Valley. (Marit Hesby)

23. Two views from Mardan Top, at the southern end of the Warwan Valley. (Authors’ archive)

24. David Mackie and Kim Housego were seized by Pakistan-backed militants in June 1994 and held for seventeen days. (AP)

25. Letter written by Hans Christian Ostrø to his family and the Norwegian Embassy shortly after his capture. (Marit Hesby)

26. Ostrø arranged for several batches of photographs, on which he wrote cryptic clues as to the hostages’ condition and location, to be smuggled out of the Warwan. (Marit Hesby)

27. The contents of Hans Christian Ostrø’s money belt, recovered from his tent at Zargibal. (Authors’ archive)

28. Press conference given by Jane Schelly and Julie Mangan, Srinagar, July 1995. (Authors’ archive)

29. Photograph of Paul Wells thought to have been taken in the wooden guesthouse in Sukhnoi village, Warwan, where the hostages were kept for several weeks. (Bob Wells)

30. Photograph taken by al Faran in August 1995 that served as a prelude to ‘proof of life’ conversations that followed. (Authors’ archive)

31. In the years following the kidnapping, the families of the hostages announced several rewards for information leading to the return of their loved ones. (Bob Wells)

32. Jehangir Khan, a commander of the pro-government renegades. (Javid Dar, 2008, courtesy of Conveyor magazine)

33. Kashmiri women passing an Indian Central Reserve Police Force patrol. (Faisal Khan, 2011, courtesy Conveyor magazine)

34. The last confirmed photograph of the hostages. (Bob Wells)

35. Identity card of renegade field commander Basir Ahmad Wagay, aka ‘the Tiger’. (Authors’ archive)

36. Renegade commander Azad Nabi, call-sign ‘Alpha’. (Authors’ archive)

37. Naseer Mohammed Sodozey, a treasurer of Harkat ul-Ansar (the Movement). (Authors’ archive)

38. Omar Sheikh, from London, arrested in Pakistan in 2002 in connection with the kidnapping of Daniel Pearl. (AP)

39. Masood Azhar in Pakistan in January 2000. (AP)

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

THE HOSTAGES

John Childs – a forty-two-year-old explosives and ordnance engineer from Connecticut, USA

Dirk Hasert – a twenty-six-year-old student on a gap year from Bad Langensalza, Germany

Kim Housego – a sixteen-year-old British boy, kidnapped while on a family holiday in Kashmir in 1994

Don Hutchings – a forty-two-year-old neuropsychologist and mountaineer from Spokane, Washington State, USA

David Mackie – a thirty-six-year-old British film producer, kidnapped in 1994 alongside Kim Housego

Keith Mangan – a thirty-three-year-old electrician from Middlesbrough, England

Hans Christian Ostrø – a twenty-seven-year-old actor and director from Oslo, Norway

Paul Wells – a twenty-four-year-old photography student from Blackburn, England

THE WIVES AND GIRLFRIENDS

Anne Hennig – Dirk’s girlfriend, a student

Julie Mangan – Keith’s wife

Catherine Moseley – Paul’s girlfriend, a social worker

Jane Schelly – Don’s wife, a PE teacher and mountaineer

THE FAMILIES

Joseph and Helen Childs – John Childs’ parents, from Salem, upstate New York, USA

Marit Hesby and Anette Ostrø – Hans Christian’s mother, a travel agent, from Oslo, Norway, and his younger sister, a film-maker then based in Stockholm

David and Jenny Housego – former Financial Times South Asia Bureau Chief, and his wife, a businesswoman, parents of Kim Housego

Claude and Donna Hutchings – parents of Don Hutchings, from Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, USA

Charlie and Mavis Mangan – Keith’s retired father and his mother, a school dinner lady, from Brookfield, Middlesbrough

James and Joyce Schelly – Jane Schelly’s parents, from Orefield, Pennsylvania, USA

Robert and Anita Sullivan – Julie Mangan’s parents, from Eston, Middlesbrough

Bob and Dianne Wells – Paul’s parents, from Blackburn

WESTERN DIPLOMATS AND INVESTIGATORS

Philip Barton – First Secretary at the British High Commission, New Delhi

Tim Buchs – Second Secretary at the US Embassy, New Delhi

Frank Elbe – German Ambassador to India

Sir Nicholas Fenn – British High Commissioner to India

Tore Hattrem – Political Officer at the Norwegian Embassy, New Delhi

Gary Noesner – lead hostage negotiator of the FBI’s Crisis Negotiation Unit

Commander Roy Ramm – hostage negotiator, head of Scotland Yard’s specialist operations

Arne Walther – Norwegian Ambassador to India

Frank Wisner – US Ambassador to India

J&K POLICE AND OFFICIALS

IG Paramdeep Singh Gill – police chief who instigates his own al Faran inquiry

DSP Kifayat Haider – police officer with operational responsibility for Pahalgam

SP Farooq Khan – the first STF chief

General K.V. Krishna Rao – former chief of the Indian Army and Governor of Kashmir

DG Mahendra Sabharwal – Kashmir police chief

SP Mushtaq Sadiq – officer leading the al Faran Squad

Lt. General (rtd) D.D. Saklani – Security Advisor to the Governor of Kashmir

IG Rajinder Tikoo – Crime Branch chief, who leads the negotiations with al Faran

SSP Bashir Ahmed Yatoo – senior Kashmiri police officer seconded to Kashmir State Human Rights Commission to investigate unmarked graves in 2011

THE KASHMIRI PRESS PACK

Mushtaq Ali – photographer for AFP. Rescued Kim Housego and David Mackie in 1994, and worked closely with Yusuf Jameel in 1995

Yusuf Jameel – the BBC’s Srinagar correspondent, instrumental in digging up the story behind the 1995 kidnapping

THE JIHADIS

‘The Afghani’ (Sajjad Shahid Khan) – the Movement’s military commander, a veteran Pashtun fighter from the Afghan–Pakistan border

Master Allah Baksh Sabir Alvi – retired schoolteacher and father of Masood Azhar

Masood Azhar – the jailed General Secretary of Harkat ul-Ansar (the Movement for the Victorious), from Bahawalpur, in the Pakistan Punjab, who later became the head of Jaish-e-Mohammed (the Army of Mohammed)

‘Brigadier Badam’ – pseudonym for a senior ISI officer who was instrumental in establishing the ISI’s proxy war in Indian Kashmir

Maulana Fazlur Rehman Khalil – Masood Azhar’s mentor in Karachi. The spiritual leader of the Movement

Nasrullah Mansoor Langrial – famed jihadi commander from Langrial, Pakistan, chosen as deputy to the Afghani and known in jihadi circles as ‘Darwesh’

Omar Sheikh – former student at the London School of Economics, who became a kidnapper for the Movement in 1994. Also involved in the 2002 abduction of American journalist Daniel Pearl

‘Sikander’ (Javid Ahmed Bhat) – southern commander of the Movement, from Dabran village, in Anantnag, Kashmir

Naseer Mohammed Sodozey – a senior fighter in the Movement, captured in April 1996 and forced under torture to incriminate himself in the 1995 kidnappings

‘The Turk’ (Abdul Hamid al-Turki) – field commander of al Faran, a veteran mujahideen fighter of Turkish ancestry

Qari Zarar – Kashmiri deputy commander of al Faran, from Doda, in Jammu

THE PRO-GOVERNMENT RENEGADES

‘Alpha’ or ‘Azad Nabi’ (Ghulam Nabi Mir) – renegade commander based in Shelipora, above Anantnag

‘Bismillah’ – Alpha’s deputy, based in Shelipora

‘The Clerk’ (Abdul Rashid) – Alpha’s district commander, based in Vailoo, above Anantnag

‘The Tiger’ (Basir Ahmad Wagay) – Alpha’s field commander, based in Lovloo, above Anantnag

ABBREVIATIONS

AFP – Agence France-Press

BJP – the Bharatiya Janata Party, a conservative Hindu nationalist political party

BSF – Border Security Force, a paramilitary outfit raised by India after its war with Pakistan in 1965 and later employed in Kashmir on counter-insurgency operations

CRPF – Central Reserve Police Force, the paramilitary police inducted into Kashmir to fight the insurgency

DG – Director General of Police. The force’s chief

DIG – Deputy Inspector General of Police

DSP – Deputy Superintendent of Police

HM (Hizbul Mujahideen: ‘the Party of the Holy Warriors’) – a Kashmiri militant outfit, formed in 1989, heavily backed at first by Pakistan

HuA (Harkat ul-Ansar: ‘the Movement for the Victorious’) – a group formed in Pakistan in 1993 by the combination of three jihad fronts, including Harkat ul Mujahideen, to rally insurgents fighting India in Kashmir. Designated as a terrorist organisation by the US in 1997

HuM (Harkat ul-Mujahideen: ‘the Order of Holy Warriors’) – formed in Pakistan in the mid-1980s by Maulana Khalil to fight the Soviets in Afghanistan. The precursor of Harkat ul-Ansar

IB – Intelligence Bureau, Indian domestic intelligence

IG – Inspector General of Police

IPS – Indian Police Service

ISI – Inter Services Intelligence directorate, Pakistan’s military intelligence agency

J&K – Jammu and Kashmir

JKLF – Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front, formed in Birmingham, UK, in 1977; one of the first militant outfits to mount an armed struggle against India in Kashmir

JKSLF, or SLF – Jammu and Kashmir Students Liberation Front, also known as the Students Liberation Front. Formed in Kashmir in 1987

LoC – Line of Control, the 406-mile-long ‘ceasefire line’ that separates the Indian and Pakistan sections of the divided state of Jammu and Kashmir

POK – Pakistan Occupied Kashmir, as the Indians sometimes refer to the section of the state administered by Islamabad

RAW – Research and Analysis Wing, Indian foreign intelligence

RR – Rashtriya Rifles, an Indian Army force of specialist counter-insurgency troops, formed in 1990 to fight the insurgency in Kashmir

RSS – Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, a Hindu paramilitary movement founded in 1925 to oppose British colonialism

SHRC – State Human Rights Commission, an Indian government body that investigates allegations of human rights abuses

SP – Superintendent of Police

SSP – Senior Superintendent of Police

STF/SOG – police Special Task Force, later renamed the Special Operations Group, founded in 1993 to fight the insurgency in Kashmir

PROLOGUE

On 1 May 2011, a Prowler electronic-warfare aircraft, taking off from the USS Carl Vinson, jammed Pakistan’s radar systems, silence spreading like emulsion over the Islamic republic. At fifty-six minutes past midnight on the morning of 2 May, two American stealth Hawks, ferrying a team of US Navy Seals, hovered over a walled compound in the spick-and-span garrison town of Abbottabad, seventy-two miles north of Islamabad, the Pakistani capital.

Over the next few minutes, Operation Neptune Spear came to a head, achieving, with only a dozen shots fired, what John Brennan, President Obama’s chief counter-terrorism advisor would call the ‘defining moment’ in the war against terrorism.

Winkled out of his hiding place by cruising satellites capable of measuring the length of a man’s shadow from six hundred miles up, while down on the ground a medical-aid camp established to counter polio in Abbottabad had been subverted to sniff out residents’ DNA, the elusive Osama bin Laden had finally been tracked down, a decade after 9/11. As he reached across his bed for his AK-47 he was shot dead, ‘decapitating the head of the snake that is al Qaeda’, according to Brennan.

One chapter in a story of our times had come to an end.

Sixteen years earlier, in the heights of the Indian Himalayas, where the mountains gather in a half-hitch to encompass the troubled valley of Kashmir, a crime was committed whose nature and cruelty presaged the age of terror Osama would go on to marshal.

In July 1995, high in the mountains of Kashmir, six Western trekkers – two Britons, two Americans, a German and a Norwegian – were seized by a group of Islamic guerrillas who demanded the release of twenty-one named militants imprisoned in Indian jails in exchange for their lives. At the head of the list was Masood Azhar, a portly cleric from Pakistan.

Masood Azhar’s early career mirrored that of Osama. Growing up in Pakistan’s eastern Punjab province in the seventies and eighties, Masood, the spoiled favourite son of a wealthy landowner, had lacked for nothing – much like the privileged young Osama, whose well-connected family made its fortune constructing palaces for Saudi royals. Educated in an Islamist hothouse in the frenetic port city of Karachi, in Pakistan’s deep south, Masood graduated to become the mouthpiece for a guerrilla outfit that would, like Osama, gravitate to Afghanistan to fight the occupying Soviet Red Army to a standstill.

When Moscow retreated from Kabul in 1989, Masood and his unemployed fighters had converged on northern Africa, looking for new causes. They found Osama there too, well before ‘the Sheikh’ had been flagged up on Western watchlists. Together, Masood, a stubby firebrand, whose hypnotic patter had already propelled thousands into battle, and Osama, the lean and pensive fugitive whose deep war chest had bought matériel and men, began to direct Afghanistan veterans in a new fight against the West.

They struck first in broken Somalia in 1993, where America was bogged down in a peacekeeping mission, Masood and Osama arming Islamists with rocket-propelled grenades that brought down two US Black Hawks in the battle for Mogadishu, leaving nineteen American soldiers dead and seventy-three wounded in a bloody débâcle. Masood was soon travelling again, this time to Britain, where he raised more funds and recruited jihadi sleepers who would wait the best part of a decade before attaining notoriety in both the West and the East.

However, in 1994, while Osama was consolidating his front in Sudan and Yemen, buying a commercial airliner and shipping weapons and gold around the world, Masood became temporarily unstuck while sowing the seeds of insurrection in Kashmir. Slipping into India on false papers, hoping to galvanise a flagging local Muslim insurgency, he was captured by the Indian Army. It was this event that led to the kidnappings of July 1995.

The fate of Masood, and the bloodshed and intrigue that engulfed the six Western trekkers, would shape much of the epoch that followed. In the mountains of Kashmir that summer, Masood’s gunmen experimented with the tactics and rhetoric of Islamic terror, unveiling to the world extreme acts and justifications that would soon become all too familiar.

Finding and squeezing Western pressure points, testing foreign governments’ sensibilities and resolve, this hostage-taking would enable Masood and his men to refine their methods before they combined forces with Osama’s al Qaeda, soon assisted by the black-turbanned Taliban when they came to power in Afghanistan in 1996.

It would only be a short leap from the kidnappings in Kashmir to suicidal assaults in Srinagar, New York, Washington and London, in which many thousands would die or be injured. Three months after 9/11, India accused Masood of being behind a brazen raid on its parliament in New Delhi, an assault that was broadcast across the subcontinent, just as the Twin Towers had fallen before a live TV audience around the world.

In 2002, Masood’s bodyguard and one of his British recruits adapted tactics honed during the Kashmir kidnapping to abduct Daniel Pearl, a Wall Street Journal reporter, and to film his horrific beheading. Masood himself, like Osama, slipped from public view, becoming a shadowy éminence grise. In 2004 he welcomed several British Pakistanis back to the land of their forefathers, and in the terrorist training camps of north-west Pakistan he helped them plan for the mayhem they would unleash in London in July 2005, when four near-simultaneous suicide bombs went off in the heart of the heaving capital, killing fifty-two and injuring more than seven hundred.

In 2006, another of Masood’s British protégés manipulated jihadi recruits from the West to mount a complex plot to bring down multiple airliners over the Atlantic with liquid bombs smuggled aboard in soft-drinks bottles. Many more plots in India, the US and the UK were narrowly thwarted, saving untold lives. By the time Osama bin Laden was run to ground in Abbottabad, many others from al Qaeda’s top table had perished too. Apart from Masood Azhar.

He continues to thrive, flitting today between Pakistan’s borders and his old home in Punjab. Four of the tourists seized in Kashmir in the summer of 1995, whose abduction foretold a new age of terror, simply vanished. Their bodies were never found, and their case was forgotten. Until now.

When the book was first published it provoked a storm in India, with the government challenged by national newspapers and cable news networks to respond, New Delhi giving the New York Times a date by when it would. That day came and went. However, lawyers in Kashmir representing the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP), an organisation representing some of the estimated 8,000 Valley dwellers who are said to have vanished after being taken into the custody of the Indian security forces, picked up the baton. The organisation filed a petition with the Indian government’s Human Rights Commission in the spring of 2012, alleging that the army and government had deliberately misled the investigation into the kidnappings and withheld information. They also suggested that a criminal network had been formed between the kidnappers and government militiamen that worked together to keep the hostages hidden from view. They demanded the case file be made public and that senior policeman be called in for questioning. On April 17, the commission agreed to review the seventeen-year-old case, triggering headlines around the world, from Fox News in the US to the BBC in London.

By July, the police had declined to react to the judge’s request to produce the Al Faran file, with the Inspector General warned by the commission that action would be taken against him. Finally, on August 13, five months after the case was listed, the J&K police Crime Branch submitted its official response. They claimed that the master file, containing key evidence, ‘went to ashes due to a fire incident’. The case is ongoing but the army and intelligence services are immune from investigation and will escape the probe.

CATHY SCOTT-CLARK AND ADRIAN LEVY

London, April 2013