Raamatut ei saa failina alla laadida, kuid seda saab lugeda meie rakenduses või veebis.

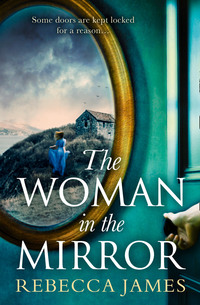

Loe raamatut: «The Woman In The Mirror»

REBECCA JAMES was born in 1983. She worked in publishing for several years before leaving to write full-time, and is now the author of eight previous novels written under a pseudonym. Her favourite things are autumn walks, Argentinean red wine and curling up in the winter with a good old-fashioned ghost story. She lives in Bristol with her husband and two daughters.

Copyright

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2018

Copyright © Rebecca James 2018

Rebecca James asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © June 2018 ISBN: 9781474073172

For the little soul

who wrote this book with me.

Shade of a shadow in the glass,

O set the crystal surface free!

Pass – as the fairer visions pass –

Nor ever more return, to be

The ghost of a distracted hour,

That heard me whisper, ‘I am she!’

MARY ELIZABETH COLERIDGE

Contents

Cover

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher

Prologue

Cornwall, winter 1806

Listen! Can you hear it?

There, right there. Listen. You are not listening. Listen hard.

Listen harder.

I hear them before I see them. Their shouts come from across the hill, calling my name, calling me Witch. They come with their spikes and flames, their red mouths and their black intent. They say I am the one to fear, but the fear is with them. Fear is in them. It has no need of me. Their fear will catch them at the final hour.

Shadows crawl over the moors, spreading dark against dark. Their torches dance, lit from the fire at the barn. Burn her! Drown her! Smoke her from her hole!

Witch.

It is not safe for me here. They will touch their fires to my home and I will perish inside. So I escape into the night, their steps bleeding close on the wind like a dread gallop. Down the cliffs, low to the ground, the sky watches, patient and indifferent. Stars are frozen. Moon observes. I cannot turn back: my home is lost.

At the end I will put myself there again, sitting by my hearth and staring at the painting on the wall. It is the painting I did for him but never gave him, a likeness of my house for he had admired it so; he had said what a perfect spot it held, high on the cliffs, a sweet little cottage circled by hay and firs. Oh, for those first days of innocence! For those days of blind hope, before he turned me away. On the night I planned to bestow the painting on him, he broke my heart. The gift I had meant for him remained with me, just as did every other part I imagined I would share.

I never thought I would be a woman for love, or a woman to be loved.

A woman should always trust herself.

What will remain at my home, after I am gone? What will he keep and what will he burn? I fear for my looking glass, my beloved mirror. I pray that it survives, for I wonder if a piece of me, however small, might survive with it.

Ivan. My love. How could you?

I shall never know. I will never understand. What is the point, now, in any case? Ivan de Grey betrayed me. I believed that he worshipped me, I swallowed his deceits and oh, it hurts, it hurts, to think of his arms around me…

Now they have built their case against me. They have shaped their fight and honed their resolve. There is nothing I can say or do; to protest confirms my fate.

I spill down the cliff path. I know it well enough in the dark. Brambles tear my skin and eyes; blood tastes sour in my mouth. I stumble, holding mud and air. My head hits a rock, sharp, hard, and I fall until a pain pulls me back, my hair caught on a stalk. For a moment, I lie still. Thunder, thunder, thunder. I gaze up at the night, the cool white pearl of the moon. I wish I were an animal. I wish I were a wolf. I wish I would transform, and be waiting for them when they come over the edge. I would leap at them with my jaws thrown wide.

But I am a woman. Not a wolf. Perhaps I am something in between.

Run.

I meet the sea, which has swallowed the sand completely. It foams around my ankles and I wade through it, salt burning the cuts on my legs. Ivan long ago decided I was marked. He saw the red on my body and the rest was easy. He told his friends and those friends told their enemies, and all are united in the crusade. Witch.

All he had to do was to make her believe in his love.

Love.

Rotten, stinking, hated love. Love is for fools, bound for hell.

I detest its creeping treacheries. I resent the shell it made of me. My weakness to be wanted, my pathetic, throbbing heart…

There is comfort in knowing that while I die, my hatred lives on. My hatred remains here, on this coast, in this sea and under this sky. My hatred remains.

I trust it with my vengeance, for vengeance I will take.

The water pulls me to my knees, black and thrashing and soaking my dress.

I turn to shore. High on the hill is a bright, living blaze. The men stride towards me, stride through the sea. I will not go with them. I will go on my own, willingly. I will swim to the deep and deeper still. I will picture my home as I drown.

I crawl into the wild dark.

A hand grabs my ankle and pulls me down.

Chapter 1

London, 1947

‘Alice Miller – for heaven’s sake, wake up.’

It might be Mrs Wilson’s uppity remark that jolts me out of my eleven o’clock reverie, or else it’s the warm muzzle of the Quakers Oatley & Sons’ resident Red Setter as it nudges hotly against my lap, for it’s hard to know which happens first.

‘I’m awake,’ I tell her, finding the dog’s warm ears under my desk and working them through my fingers; Jasper breathes contentedly through his nose and his tail bangs on the floor. ‘Can’t you see my eyes are open?’

Mrs Wilson, the firm’s stuffy administrator, draws deeply on her cigarette, sucking in her cheeks. She dispels a plume of smoke before grinding the cigarette out in an ashtray. She pushes her glasses on to the bridge of her nose.

‘I wouldn’t suggest for a moment, Miss Miller, that your eyes being open has the slightest thing to do with it.’ Her fingers clack-clack on the typewriter. ‘It doesn’t take a fool to see that you’re miles away. As usual.’

If I were able to dispute the accusation, I would. But she’s right. There is little about being a solicitor’s secretary that I find stimulating, and my memories too often call me back. This is not living, as I have known living. Haven’t we all known living – and dying – in ways impossible to articulate? But to look in Jean Wilson’s eyes, just two years after wartime, as flat and grey as the city streets seem to me now, it’s as if that world might never have existed; as if it had been just one of my daydreams. I wonder what Mrs Wilson lost during those years. It is easy for one to feel as though one’s own loss overtakes all others’ – but then one remembers: mine is a lone story, a single note in a piece of music that, if played back many years from now, would be obscured by the orchestra that surrounds it.

Jasper pads out from under the desk and settles on a rug by the window. Through it, I hear the noisy brakes of a bus and a car tooting its horn.

The telephone rings. ‘Good morning, Quakers Oatley?’

We are expecting a call from an irksome client but to my surprise it is not he. For a moment, I hear the crackle of the line and the faint echo of another exchange, before a smart voice introduces itself. My grip tightens. I’m quiet for long enough that Mrs Wilson’s interest is aroused. She glances at me over the top of her spectacles.

‘Of course,’ I say, once I’ve taken in all that he’s said. ‘I’ll be with you right away.’

I replace the telephone, retrieve my coat and open the door.

‘Where are you going?’

‘Goodbye, Mrs Wilson.’ I put on my coat. ‘Goodbye, Jasper.’

It is the last time I will see either of them.

*

The Tube still smells as it did in the war – fusty, sour, hot with bodies. Next to me on the platform is a woman with her children; she smacks one of them on the hand and tells him off, then pulls both to her when the train comes in. I imagine her down here during the Blitz, when they were babies, holding them close while the sky fell down.

I take the train to Marble Arch, repeating the address as I go. The building is closer than I think and I’m here early, so I step into a café next door and order a mug of tea. I drink it slowly, still wearing my hat. A man at the table next to me slices his fried egg on toast so that the yoke bursts over his plate and an orange bead lands on the greasy, chequered oilcloth. He dabs it with his finger.

I’ve kept the advertisement in my handbag for a month. I didn’t think anything would come of it; the opportunity seemed too niche, too unlikely, too convenient. GOVERNESS REQUIRED, FAMILY HALL NR. POLCREATH, IMMEDIATE APPOINTMENT. I spied it during a sandwich break, in the back of the county paper Mrs Wilson brought home from a long weekend in the South West.

I unfold it and read it again. There really isn’t any other information, nothing about the people I would be working for or for how long the position might be. I question if this isn’t what drew me towards the prospect in the first place. My life used to be full of uncertainties: each day was uncertain, each sunrise and sunset one that we didn’t expect to see; each night, while we waited for the bombs to drop and the gunfire to start, was extra time we had somehow stumbled into. Uncertainty kept me alive, knowing that the moment I was in couldn’t possibly last for ever and the next would soon be here, a moment of change, of newness, the ground shifting beneath my feet and moving me forward. At Quakers Oatley, the ground sticks fast, so fast I feel myself drowning.

The tea turns tepid, the deep cracked brown of a terracotta pot, and a fleck of milk powder floats depressingly on its surface. The man next to me grins, flips out his newspaper: India Wins Independence: British Rule Ends. I sense him about to speak and so stand before he can, buttoning my coat and checking my reflection in the smeared window. I pull open the café door, its chime offering a weak ring.

There it is, then. No. 46. Across the road, the genteel townhouse bears down, its glossy black door and polished copper bell push like a delicately wrapped present that my fumbling fingers are desperate, yet fearful, to open. Before we begin, it has me on the back foot. I need it more than it needs me. This job is my ticket out of London, away from the past, away from my secrets. This job is escape.

*

‘Welcome, Miss Miller. Do please sit down.’

I peel off my gloves and set them neatly on the desk before changing my mind and scooping them into my bag. I set the bag on my lap, then have nowhere to put my hands, so I place the bag on the floor, next to my ankles.

He doesn’t appear to notice this display, or perhaps he is too polite to acknowledge it. Instead, he takes a file from the drawer and flicks through it for several moments. The top of his head, as he bends, is bald, and clean as a marble.

‘Thank you for meeting us at short notice,’ he says, with a quick smile. ‘My client, as you’ll understand, prefers to be discreet, and often that means securing results swiftly. We would prefer to resolve the appointment as soon as possible.’

‘Of course.’

‘You have experience with children?’

‘I used to nanny our neighbours’ infants, before the war.’

He nods. ‘My client’s children require tutelage as well as pastoral care. We are concerned with the curriculum but also with a comprehensive education in nature, the arts, sports and games – and, naturally, refinement of etiquette and propriety.’

I sit straighter. ‘Naturally.’

‘The twins are eight years old.’ His eyes meet mine for the first time, sharp and glassy as a crow’s.

‘Very good.’

‘I’m afraid this isn’t the sort of position you can abandon after a month,’ he says. ‘If you find it a challenge, you can begin your instruction by teaching these children the knack of perseverance.’ He puts his fingers together. ‘I mention this because my client lost his last governess suddenly and without warning.’

‘Oh.’

‘As a widower, he has understandably struggled. These are difficult times.’

I’m surprised. ‘Did his wife die recently?’

Immediately I know I have spoken out of turn. I am not here to question this man; he is here to question me. My interest is unwelcome.

‘Tell me, Miss Miller,’ he says, bypassing my enquiry with ease, ‘what occupation did you hold during the war?’

‘I volunteered with the WVS.’

The man teases the end of his moustache. ‘Nurturing yet capable: would that be a fair assessment?’

‘I’d suggest the two aren’t mutually exclusive.’

He writes something down.

‘Have you always lived in London?’

‘I grew up in Surrey.’

‘And attended which school…?’

‘Burstead.’

His eyebrow snags, impressed but not liking to show it. I know my education was among the finest in the country. My mother was schooled at Burstead, and my grandmother before that. There was never any question that my parents would send me there. I tighten my fists in my lap, remembering my father’s face over that Sunday lunch in 1940. The ticking of the mantle clock, the shaft of winter sunlight that bounced off the table, the smell of burned fruit crumble… His rage when I told him what I had done. That the education they had bought for me had instead brought a nightmare to their door. The sound of smashing glass as my mother walked in, letting the tumbler fall, shattering into a thousand splinters on the treacle-coloured carpet.

He clears his throat, tapping the page with his pen. I see my own handwriting.

‘In your letter,’ he says, ‘you say you are keen to move away from the city. Why?’

‘Aren’t we all?’ I answer a little indecorously, because this is easy, this is what he expects to hear. ‘I would never care to repeat the things I have seen or done over the past six years. The city holds no magic for me any more.’

He sees my automatic answer for what it is.

‘But you, personally,’ he presses, those eyes training into me again. ‘I am interested in what makes you want to leave.’

A moment passes, an open door, the person on each side questioning if the other will walk through – before it closes. The man sits forward.

‘You might deem me improper,’ he says, ‘but my inquests are made purely on my client’s behalf. We understand that the setting of your new appointment is a far cry from the capital. Are you used to isolation, Miss Miller? Are you accustomed to being on your own?’

‘I am very comfortable on my own.’

‘My client needs to know if you have the vigour for it. As I said previously, he does not wish to be hiring a third governess in a few weeks’ time.’

‘I’ve no doubt.’

‘Therefore, if you will forgive my impudence, could you reassure us that you have no medical history of mental disturbances?’

‘Disturbances?’

‘Depressive episodes, attacks of anxiety, that sort of thing.’

I pause. ‘No.’

‘You cannot reassure us, or you can that you haven’t?’

For the first time, there is the trace of a smile. I am almost there. Almost. I don’t have to tell him the truth. I don’t have to tell him anything.

‘I can reassure you that I am perfectly well,’ I say, and it trips off my tongue as smoothly as my name.

The man assesses me, then squares the paper in front of him and replaces it in its folder. When he leans back in his chair, I hear the creak of leather.

‘Very well, Miss Miller,’ he says. ‘My client entrusts me with the authority to hire at will in light of my appraisal of an applicant’s suitability, and I am pleased to offer you the position of governess at the Polcreath estate with immediate effect.’

I rein in my delight. ‘Thank you.’

‘Before you accept, is there anything you would like to ask us?’

‘Your client’s name, and the name of the house.’

‘Then I must insist on your signature.’

He slides a piece of paper across the desk, a contract of sorts, listing my start date as this coming week, the broad terms of my responsibilities towards the children, and that my bed and board will be provided. There is a dotted line at the foot, awaiting my pen. ‘I understand it is unorthodox,’ he says, ‘but my client is a private man. We need assurance of your allegiance before I’m permitted to give details.’

‘But until I have details I have little idea what I am signing.’

The man holds his hands up, as if helpless. I wait a moment, but there is never any hesitation in my mind. I collect the pen and sign my name.

Chapter 2

My train pulls into Polcreath Station at four o’clock on Sunday. The warmth has gone out of the day and a rich, autumn sun sits low on the horizon, casting the land in a burned harvest glow. I’m quick to see the car, but then it’s hard to miss, a smart, black Rolls-Royce whose white wheels gleam like bones in the fading light.

A man greets me, short, middle-aged, fair. ‘Miss Miller?’

‘How do you do.’

He lifts my bags into the car then opens the rear door for me. Up close, the Rolls is more decayed than it first appeared. Its paintwork is peeling and inside the upholstery is fissured and coming away from the seat frames. There is the smell of old cigarettes and petrol. It takes the chauffeur a moment to start the engine.

‘I’m Tom, Winterbourne’s houseman,’ he says, when I ask him: not a chauffeur after all, then. ‘I’ll turn my hand to anything.’ He has a gentle Northern accent and a friendly, easy manner. ‘There’s not many of us – just me and Cook. And you, now, of course. The house can’t afford anyone else, though goodness knows we need it. We’re mighty excited to have you joining us, miss. Winterbourne always seems darker at this time of year, when the evenings draw in and the light starts to go. The more company the better, I say.’

‘Please, call me Alice.’

‘Right you are, miss.’

I smile. ‘Is it far to Winterbourne?’

‘Not far. Over the bluff. The sea makes it seem further – there’s a lot of sea. Are you used to the sea, miss?’

‘Not very. One or two holidays as a child.’

‘The sea’s as much a part of Winterbourne as its roof and walls. I expect that sounds daft to a city lady like yourself, but there it is. You can see the sea from every window, did they tell you that?’

‘They didn’t tell me much about anything.’

Tom crunches the gears. ‘This car’s a bad lot. The captain would never part with it, but really we’d be better off with a horse and cart, at the rate this thing goes.’

‘More comfortable, though, I’d wager.’ Although I’m being generous: with every bump and rut in the road the car squeaks in protest, and the springs in my seat dig painfully into my thighs. The short distance Tom promised is ever lengthening. In time we come off the road and on to a track, on either side of which the countryside spreads, a swathe of dark green that eventually gives way, if I squint into the distance, to a flat sheet of grey water.

‘The moors look tame from here,’ says Tom, with a quick glance over his shoulder, ‘but wait till we reach the cliffs. It’s a sheer drop there – ground beneath your feet one moment, then nothing. You’ve got to be careful, miss. The mists that come in off the sea are solid. Some days you can’t see more than a foot or two in front, you can’t see a thing. All you’ve got to go on is the sound of the sea, but if you lose your bearings with that, one wrong step and you’re gone. Winterbourne’s right on the bluff. Some people say it’s the second lighthouse at Polcreath.’

‘How long have you worked for the captain?’

‘Since before the war. I knew him when he was a…different sort of person. The war changed people, didn’t it? Just because you have a title, or a place like Winterbourne, it doesn’t spare you. He was hurt in France; it’s been hard for him, an able-bodied man like that suddenly made a cripple. Did the war change you, miss?’

I focus on the horizon, an expanse of steel coming ever closer, and concentrate on the clean line of it so intently that I can’t think of anything else. ‘Of course.’

‘Between you and me, I could likely find better-paid employment elsewhere, but I’ve got loyalty for Winterbourne, and for the captain. My mother used to say that you’re nothing without your friends. The captain would never say I was a friend, but he doesn’t say a lot of things that he might really mean.’

‘How tragic that he lost his wife.’

‘Indeed, miss.’ There’s a laden silence. ‘But we don’t speak about that.’

I sit back. I had hoped that Tom’s loquaciousness might lend itself to a confidence, but seemingly not on this matter. Two people now have refused to speak to me about the former woman of the house. What happened to her?

I am expecting us to come across the Hall suddenly, to catch a quick glimpse of it between trees or to swing abruptly through the park gates, but instead I spot it first as a ragged smudge on the hill. That’s how it appears – as an inkblot the size of my thumb, spilled in water, its edges seeming to fall away or dissolve into air. There is something about its position, elevated and alone, that reminds me of a fortress in a storybook, or of a drawing of a haunted house, its black silhouette set starkly against the deepening orange of the sky. As we approach, I begin to make out its features. To say that Winterbourne is an extreme-looking house would be an understatement.

It’s hard to imagine a more dramatic façade. The place instantly brings to mind an imposing religious house – a Parisian cathedral, perhaps, decorated with gaping arches and delicate spires. Turrets thrust skyward, and to the east the blunt teeth of a battlement crown remind me of a game of chess. Plunging gargoyles are laced around its many necks, long and thin, jutting, as if leaping from the building’s skin. Lancet windows, too many to count, adorn the exterior, and set on the western front is what appears to be a chapel. I was scarcely aware of having entered the park, and it strikes me that we must have crossed into it a while ago; that the land we’ve been driving on all this time belongs to Winterbourne.

Gnarled trees creep out of the drowning afternoon. To our left, away from the sea, spreads a wild, dark wood, dense with firs and the soft black mystery of how it feels to be lost, away from home, when you are a child and the night draws close. On the other, the sea is a wide-eyed stare, lighter and smoother now we are near, like pearls held in a cold hand. I see what Tom meant about the drop from the cliffs: the land sweeps up and away from the hall, a brief sharp lip like the crest of a wave, and then it is a four-hundred-foot plummet to the rocks. Further still into that unblinking spread I detect Polcreath Point, the tower light, a mile or so from the shore.

‘Here we are, miss.’ Tom turns the Rolls a final time and we embark up the final stretch towards the house, a narrow track between overgrown topiary. Leafy fingers drag against the windows, and the car rocks over a series of potholes that propels my vanity case into the foothold. At last we emerge into an oval of gravel, at the centre of which is an unkempt planter, tangled with weeds.

‘Winterbourne Hall.’

I gaze up at my new lodgings, and imagine how my arrival must look. A throbbing engine, a lonely car – and a woman, peering skyward, her hand poised to open the door, and some slight switch of nameless apprehension that makes her pause.

*

The first thing I notice is the smell. It isn’t unpleasant, merely unusual, a liturgical smell like the inside of a church: wood, stone and burning candles.

There are no candles burning. The entrance is gloomy, lit by a flickering candelabrum. ‘Ticky generator,’ explains Tom, taking off his cap. ‘We use fires, mostly.’ I look up at the chandelier, its bulbs bruised with dust and casting an uncertain glow that sends tapered shadows across the walls. The ceiling is ribbed and vaulted, like the roof of a basilica, but its decorations are bleached and crumbled. A staircase climbs ahead of me, a faded scarlet runner up its centre, bolted in place by gold pins. Some of the pins are missing and the carpet frays up against the wood like a rabbit’s tail. On the upper walls, a trio of hangings in red and bronze sits alongside twisting metal sconces, better suited to a Transylvanian castle than to a declining Cornish home. There is a large stone fireplace, coated in soot, and several items of heavy Elizabethan furniture positioned in alcoves: elaborate dark-wood chairs, an occasional table, and a hulking chest with edges wreathed in nail heads.

On the landing above, I see closed doors, set with gothic forging. The windows are heavily draped in velvet, with tasselled tiebacks. Dozens of eyes watch me watching. Paintings of the captain’s ancestors bear down from every facet.

For a moment I have the uncanny sense of having been here before – then I place the connection. The headmaster’s study at Burstead. How, when a girl was called in for a flogging, she would be surrounded by an army of onlookers – those men, tyrants past, with their shining eyes and satisfied smirks, their portraits as immovable as the headmaster’s intention, and she would stand in the red punitive glow of the stained-glass window and bite her lip while the first lash came…

Afterwards, when they couldn’t decide how the tragedy had happened, they brought us all in for a whipping; perhaps they thought the belt would draw it out of us as cleanly as it drew blood to the skin. The difficulty was that nobody except me knew the truth. Nobody else had been there. They sensed a secret, dark and dreadful, rippling through the dormitories like an electrical charge, but I was the only girl who knew and I wasn’t about to share it. So I kept my lips shut and I let the lashes come for me and for the others, and time passed and term ended and school finished not long after that.

I blink, and take my gloves off.

‘Where are the children?’ I ask. ‘I should like to introduce myself.’

Tom gives me a strange look. ‘The captain asked us to settle you in first, miss. The twins can get overexcited. They like to play games.’

‘Well, they’re children, aren’t they?’

He pauses, as if my query might have some other answer.

‘What happened to their previous governess? The woman before me?’

‘She left,’ Tom replies, too quickly and smoothly for it to be the truth. ‘One morning, suddenly. We had no warning, miss, honestly. She sent word days later – a family emergency. She was mighty sad about it, hated letting the captain down. We all of us hate to let the captain down. It’d be horrible if he was let down again, wouldn’t it, miss? After the effort he’s gone to, to bring you down here. There’s only so much a man can take. The captain said there was no way round it, and the world exists outside Winterbourne whether we like it or not. Because you do feel that way, miss, here, after a while. Like Winterbourne is all there is, just the house and sea. You find you don’t need anything else.’ His expression is unfathomable, doggedly loyal.

‘Do the children miss her terribly?’ I am not sure if I am talking about the governess or the children’s mother: this pair of doomed women, for a moment, seem bound in a fundamental, terrifying way, but the thought flits free before I can catch it.