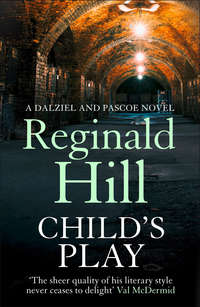

Loe raamatut: «Child’s Play»

REGINALD HILL

CHILD’S PLAY

A Dalziel and Pascoe novel

Copyright

Harper An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1987

Copyright © Reginald Hill 1987

Reginald Hill asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780586072578

EPub Edition © July 2015 ISBN: 9780007386222

Version: 2015-06-18

For Rose and Peter

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1

SECOND ACT: Voices from the Grave

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

THIRD ACT: Voices from the Gallery

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

FIRST ACT: Voices from a Far Country

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Epilogue

Keep Reading

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

Prologue

spoken by a member of the company

A simple child, dear brother Jim,

That lightly draws its breath,

And feels its life in every limb,

What should it know of death?

Wordsworth: We are seven

Chapter 1

Death? Not much. Not then, not now. What is it? You here, I there: you stopping, I going on? Unimaginable! But I can imagine dying and the fear of it. The love of it too. I can imagine a corvette in heavy seas - a bathtub vessel in harbour, but let a gale come howling up the Tyrrhenian, then in the twinkling of a dog-star, its steel sides are changed to perilous cliffs and the dinghy far below bounces on the wild waters like a baby’s teething-ring.

I can hear what the wind sings! At home, a father’s anger and a mother’s tears; at school, nipping draughts and stumbling repetitions, dreadful doubts and tiny triumphs … the sum of the squares … Lars Porsena of Clusium … a spot on the nose … a place in the Eleven … how to mash a girl … arma virumque cano!

Now I seize the rope and feel its fibres burn my frozen palms. With what strange utterance the wind resounds against this metal cliff; arms and the man, it sings … you ‘orrible sprog! … move to the right in threes! … hands off cocks and on to socks! … squeeze it like a tit! … a pip on the shoulder … a place on a course … how to kill a man …

Italiam non sponte sequor!

And now at last the gaping O receives me and suddenly it is once more a dinghy and the wind is just a wind. Master of myself finally, and of these men who kneel around me, I give commands. Eyes gleam white as fish in sea-dark faces, paddles plunge deep, and my buoyant craft drives over the grasping waves towards the sounding but unseen, the undesired but never to be evaded Ausonian shore.

Fanciful, you say? Romantic even? Oh, but I have still darker imaginings. Time blows like mist in a wind, parting and joining, revealing and concealing, and now the wind is a wind of autumn bearing with it not the salt spume of foreign seas but the bright decay of fallen leaves and the peppery scent of heather and the dust of limestone tors.

There is noise in it too, animal noise, a breathing, a coughing, an uneasy shuffling of feet as I pass over the dew-damp grass towards the darkling house. A window stands carelessly open … reckless I enter and the wind enters with me … slowly I move across the rooms … along corridors … up stairs … uncertain, hesitant, yet driven on by a gale in the blood stronger than any fear.

I push open a bedroom door … a nightlight shines like a corpse-light … but this dimly apprehended shape is no corpse.

Who’s there? Is there someone there? What do you want?

It is time to speak into this light which shows so little.

Mother?

Who’s there? Closer! Closer! Let me see!

And now the wind is a burning wind of the desert in my veins, and it sobs and it shrieks, and the house bristles with light, and I reach for the saving darkness as the helpless, hopeless sailor embraces the drowning sea …

SECOND ACT Voices from the Grave

Sweet is a legacy, and passing sweet

The unexpected death of some old lady.

Byron: Don Juan

Chapter 1

No one who attended Gwendoline Huby’s funeral would soon forget it.

Her eighty-year-old frame was lighter by far than the ornate casket that enclosed it, but the telekinetic weight of resentment from the chief mourners was enough to make the bearers stagger on their slow path to the grave.

She was buried, of course, in the Lomas plot at St Wilfrid’s in Greendale, an interesting specimen of late Norman church with some Early English additions and a pre-Norman crypt which the vicar’s wife (in a pamphlet on sale in the porch) theorized might have been the work of Wilfrid himself. Such archaeological speculation was far from the minds of the bereaved as they processed from the dark interior to the brilliant autumn sunlight which traced out the names on the tombstones of all but the most eroded and deepest lichened dead.

The surviving relatives were few. To the left of the open grave stood the two London Lomases; to the right huddled the four Old Mill Inn Hubys. Miss Keech, successively nurse, housekeeper, companion, and finally nurse once more at Troy House, essayed a crossbench neutrality at the foot of the grave, but her self-effacing tact was vitiated by the presence at her shoulder of the man generally regarded as the chief author of their woes, Mr Eden Thackeray, senior partner of Messrs Thackeray, Amberson, Mellor and Thackeray (usually known as Messrs Thackeray etcetera), Solicitors.

‘Man that is born of woman hath but a short time to live and is full of misery,’ intoned the vicar.

Eden Thackeray, who had thoroughly enjoyed the greater part of his fifty-odd years, composed his face to a public sympathy with the words. Certainly if several of those present had their way, there’d be an extra dollop of misery on his plate shortly. Not that he minded. Misery to lawyers is like the bramble-bush to Brer Rabbit - a natural habitat. As the old lady’s solicitor and executor, he was confident that any attempt to challenge the will would only serve to put money in the ever-receptive coffers of Messrs Thackeray etcetera.

Nevertheless, unpleasantness at a funeral was not, how should he put it? was not pleasant. He hadn’t relished being greeted by Mr John Huby, nephew to the deceased, landlord of the Old Mill Inn and archetypal uncouth Yorkshireman, with a look of sneering accusation and the words, ‘Lawyers? I’ve shit ’em!’

It was his own fault, of course. There had been no need to reveal the terms of the will until after probate, but it had seemed a kindness to pre-empt any anticipatory extravagance on the part of John Huby by summoning little Lexie from her typewriter and explaining to her the limits of her family’s expectations. Lexie had taken it well. She had even smiled faintly when told of Gruff-of-Greendale. But all smiles had clearly stopped together when she bore the news back to the Old Mill Inn.

No! Eden Thackeray assured himself firmly. This was the last time he let a kindly impulse move him off the well-worn rails of legal procedure, not even if he saw one of his own family chained to the line ahead!

‘Thou knowest, Lord, the secrets of our hearts …’

Aye, Lord, mebbe thou dost, and if so, nivver hesitate to pass them on to that silly old bat if she happens to drift in thy direction! thought John Huby savagely.

All those years of dancing attendance! All those cups of watery tea, supped with his little finger crooked and his head nodding agreement with her half-baked ideas on Lord’s Day Observance and preserving the Empire! All those Sunday afternoons spent crammed - no matter what the weather - into his blue serge suit, the arse of which always required a good hour’s brushing to remove the thick layer of cat and dog hair it picked up from every seat at Troy House! All that wasted effort!

And worse. All those debts run up in the expectation of plenty. All those foundations already dug and equipment already ordered for the restaurant and function room extensions. His heart fell flat as a slop-tray at the thought of it. Years of confident hope, months of tremulous anticipation, and barely twenty-four hours of joyous attainment before Lexie came home from that bloodsucking bastard’s office and broke the incredible news.

Oh yes, Lord! If like the vicar says, thou knowst what’s going on in my heart, then pass it on to the silly old bat pretty damn quick, and tell her if she hangs around a bit, she’ll likely catch Gruff-of-sodding-Greendale coming up the chimney at the Old Mill after her!

‘Forasmuch as it hath pleased Almighty God of his great mercy to take unto himself the soul of our dear sister here departed …’

The pleasure, dear God, is entirely yours, thought Stephanie Windibanks, née Lomas, first cousin once removed of the dear departed, as she grasped a handful of earth and wondered which of those around the grave would make the best target.

That low publican, Huby? Rod’s suggestion that she should console herself with the thought that she had been dealt with no worse than that creature had only fanned her resentment. To be put on a par with such an uncouth lout! Oh Arthur, Arthur! she apostrophized her dead husband, see what a pass you’ve brought me to, you stupid bastard! At least, dear God, do not let them find out about the villa!

But what was the use of appealing to God? Why should He reward faith when He was so reluctant to reward works? For it had been hard work cultivating the Yorkshire connection all these years. Of course, it might be pointed out that she had long been aware - who better? - of Cousin Gwen’s central dottiness. Indeed, she had to admit that on occasion she had even actively encouraged it. But who would have guessed that when it pleased Almighty and entirely Unreliable God of His great mercy to take Gwen’s soul unto himself, it would also amuse him to leave her dottiness wandering loose and dangerous on the terrestrial plane?

God then her target, rather than Huby? But how to strike the intangible? She wanted a satisfyingly meaty mark. What about God’s accomplice in this, that smug bastard Thackeray? It would be nice, but long experience of the world of affairs had taught her that lawyers loomed large in the ranks of the pricks it was fruitless to kick against.

Keech, then? That downmarket Mrs Danvers, peering with myopic piety at a point a little above the vicar’s head as if hoping to see there and applaud the ascension of her benefactress’s soul …

No. Keech had done well, it was true, but only in relation to her needs. And think of the price. A lifetime of those creatures and that smell …! It required the soul of an ostler to envy Miss Keech!

This then was the worst moment of all, the moment when you realized there was no one to vent your rage on, a nothingness as insubstantial as the spirit of that silly old woman doubtless smiling smugly in her satin blancmange mould six feet below!

She hurled the earth with such force against the coffin lid that a pebble rebounded straight up the vicar’s cassock, producing a little squeal of shock and pain which translated the sure and certain hope of the Resurrection into the sure and certain hype of the Resurrection. No one was surprised. Was not this, after all, the age of the New English Prayer Book?

‘I heard a voice from heaven, saying unto me, Write …’

Dear Auntie Gwen, thought Stephanie Windibanks' son, Rod Lomas, Mummy and I have come up to Yorkshire for your funeral which has been rather Low Church for my taste and rather low company for Mummy’s. You were quite right to keep these Hubys in their place, as dear Keechie puts it. They are the product of very unimaginative casting. Father John looks too like a bad-tempered Yorkshire publican to be true, and Goodwife Ruby (Ruby Huby! no scriptwriter would dare invent that!) is the big, blonde barmaid to the last brassy gleam. Younger daughter Jane is cast in the same jelly-mould and where this superfluity of flesh comes from is easy to see when you look at the elder girl, Lexie. In shape no bigger than an agate stone on the forefinger of an alderman, I swear she could enter an ill-fitting door by the joint. With those great round glasses and that solemn little face, she looks like a barn owl perched on a pogostick!

But all this you know, dear Auntie, and much else besides. What can I, who am here, tell you, who are there? Still, I must not shirk my familial obligations, unlike some I can think of. The weather here is fine, corn-yellow sun in a cornflower sky, just right for early September. Mummy is as well as can be expected in the tragic circumstances. As for me, suffice it to say that after my brilliant but brief run as Mercutio in the Salisbury Spring Festival, I am once more resting, and I will not conceal from you that a generous helping of the chinks would not have gone astray. Well, we must live in hope, mustn’t we? Except for you, Auntie, who, if you do still exist, must now exist in certainty. Don’t be too disappointed in our disappointment, will you? And do have the grace to blush when you find what a silly ass you’ve been making of yourself all these years.

Must sign off now. Almost time for the cold ham. Take care. Sorry you’re not here. Love to Alexander. Your loving cousin a bit removed,

Rod.

‘Come ye blessed children of my Father, receive the kingdom prepared for you …’

I hope the preparation’s a bit better than yours was, Dad, thought Lexie Huby, sensitive, as she had learned to be from infancy, to the rumbles of volcanic rage emanating from her father’s rigid frame. She had giggled when Mr Thackeray had told her about Gruff-of-Greendale but she had not giggled when she broke the news to her father that night.

‘Two hundred pounds!’ he’d exploded. ‘Two hundred pounds and a stuffed dog!’

‘You did used to make a fuss of it, Dad,’ Jane had piped up. ‘Said it were one of the wonders of nature, it were so lifelike.’

‘Lifelike! I hated that bloody tyke when it were alive, and I hated it even more when it were dead. At least, living, it’d squeal when you kicked it! Gruff-of-sodding-Greendale! You’re not laking with me are you, Lexie?’

‘I’d not do that, Dad,’ she said calmly.

‘Why’d old Thackeray tell you all this and not me direct?’ he demanded suspiciously. ‘Why’d he tell a mere girl when he could’ve picked up the phone and spoken straight to me? Scared, was he?’

‘He were trying to be kind, Dad,’ said Lexie. ‘Besides, I were as entitled to hear it as you. I’m a beneficiary too.’

‘You?’ Huby’s eyes had lit with new hope. ‘What did you get, Lexie?’

‘I got fifty pounds and all her opera records,’ said Lexie. ‘Mam got a hundred pounds and her carriage clock, the brass one in the parlour, not the gold one in her bedroom. And Jane got fifty and the green damask tablecloth.’

‘The old cow! The rotten old cow! Who got it, then? Not that cousin of hers, not old Windypants and her useless son?’

‘No, Dad. She gets two hundred like you, and the silver teapot.’

‘That’s worth a damn sight more than Gruff-of-sodding-Greendale! She always were a crook, that one, like that dead husband of hers. They should’ve both been locked up! But who does get it then? Is it Keech? That scheming old hag?’

‘Miss Keech gets an allowance on condition she stays on at Troy House and looks after the animals,’ said Lexie.

‘That’s a meal ticket for life, isn’t it?’ said John Huby. ‘But hold on. If she stays on, who gets the house? I mean, it has to belong to some bugger, doesn’t it? Lexie, who’s she left it all to? Not to some bloody charity, is it? I couldn’t bear to be passed over for a bloody dogs’ home.’

‘In a sense,’ said Lexie, taking a deep breath. ‘But not directly. In the first place she’s left everything to …’

‘To who?’ thundered John Huby as she hesitated.

And Lexie recalled Eden Thackeray’s quiet, dry voice … ‘the rest residue and remainder of my estate whatsoever whether real or personal I give unto my only son Second Lieutenant Alexander Lomas Huby present address unknown …

‘She’s done what? Nay! I’ll not credit it! She’s done what? It’ll not stand up! It’s that slimy bloody lawyer that’s behind it, I’ll warrant! I’ll not sit down under this! I’ll not!’

It had been an irony unappreciated by John Huby that in the old church of St Wilfrid, what he had sat down under was a brass wall plaque reading In Loving Memory of Second Lieutenant Alexander Lomas Huby, missing in action in Italy, May 1944.

It was Sam Huby, the boy’s father, who had caused the plaque to be erected in 1947. For two years he had tolerated his wife’s refusal to believe her son was dead, but there had to be an end. For him the installation of the plaque marked it. But not for Gwendoline Huby. Her conviction of Alexander’s survival had gone underground for a decade and then re-emerged, bright-eyed and vigorous as ever, on her husband’s death. She made no secret of her belief, and over the years in the eyes of most of her family and close acquaintances, this dottiness had become as unremarkable as, say, a wart on the chin, or a stutter.

To find at last that it was this disregarded eccentricity which had robbed him of his merited inheritance was almost more than John Huby could bear.

Lexie had continued, ‘If he doesn’t claim it by April 4th in the year 2015, which would be his ninetieth birthday, that’s when it goes to charity. There’s three of them, by the way …’

But John Huby was not in the mood for charity.

‘2015?’ he groaned. ‘I’ll be ninety then too, if I’m spared, which doesn’t seem likely. I’ll fight the will! She must’ve been crazy, that’s plain as the nose on your face. All that money … How much is it, Lexie? Did Mr sodding Thackeray tell you that?’

Lexie said, ‘It’s hard to be exact, Dad, what with share prices going up and down and all that …’

‘Don’t try to blind me with science, girl. Just because I let you go and work in that bugger’s office instead of stopping at home and helping your mam in the pub doesn’t make you cleverer than the rest of us, you’d do well to remember that! So none of your airs, you don’t understand all that stuff anyway! Just give us a figure.’

‘All right, Dad,’ said Lexie Huby meekly. ‘Mr Thackeray reckons that all told it should come to the best part of a million and a half pounds.’

And for the first and perhaps the last time in her life, she had the satisfaction of reducing her father to silence.

‘The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ …’

Ella Keech’s gaze was not in fact focused on some beatific vision of an ascending soul, as Mrs Windibanks had theorized. Myopic she was, it was true, but her long sight was perfectly sound and she was staring over the clerical shoulder into the green shades of the churchyard beyond. Money and descendants being alike in short supply, most of the old graves were sadly neglected, though in the eyes of many, long grass and wild flowers became the lichened headstones rather more than razed turf and cellophaned wreaths could hope to. But it was no such elegiac meditation which occupied Miss Keech’s mind.

She was looking to where a pair of elderly yews met over the old lychgate forming a tunnel of almost utter blackness in the bright sun. For several minutes past she had been aware of a vague lightness in that black tunnel. And now it was moving; now it was taking shape; now it was stepping out like an actor into the glare of the footlights.

It was a man. He advanced hesitantly, awkwardly, between the gravestones. He wore a crumpled, sky-blue, lightweight suit and he carried a straw hat before him in both hands, twisting it nervously. Around his left sleeve ran a crepe mourning band.

Miss Keech found that he became less clear the closer he got. He had thick grey hair, she could see that, and its lightness formed a striking contrast with his suntanned face. He was about the same age as John Huby, she guessed.

And now it occurred to her that the resemblance did not end there.

And it also occurred to her that perhaps she was the only one present who could see this approaching man…

‘… the fellowship of the Holy Ghost be with us all evermore. Amen.’

As the respondent amens were returned (with the London Lomas party favouring a as in ‘play’ and the Old Mill Huby set preferring ah as in ‘father’) it became clear that the fellowship of the newcomer was not so ghostly as to be visible only to Miss Keech. Others were looking at him with expressions ranging from open curiosity in the face of Eden Thackeray to vacuous benevolence on the face of the vicar.

But it took John Huby to voice the general puzzlement.

‘Wha’s yon bugger?’ he asked no one in particular.

The newcomer responded instantly and amazingly.

Sinking on his knees, he seized two handfuls of earth and, hurling them dramatically into the grave, threw back his head and cried, ‘Mama!’

There were several cries of astonishment and indignation; Mrs Windibanks looked at the newcomer as if he’d whispered a vile suggestion in her ear, Miss Keech fainted slowly into the reluctant arms of Eden Thackeray, and John Huby, perhaps viewing this as a Judas kiss, cried, ‘Nah then! Nah then! What’s all this? What’s all this? Is this another one of thy fancy tricks, lawyer? Is that what it is, eh? By God, it’s time someone gave thee a lesson in how decent folks behave at a funeral!’

So saying, and full of selfless eagerness to administer this lesson, he began to advance on Eden Thackeray. The lawyer, finding himself in the Court of Last Resources, attempted to ward him off with the person of Miss Keech. Sidestepping to get at his proper prey, John Huby’s foot found space where it looked for terra firma. For a second he teetered on one leg; then with a cry in which fear was now indistinguishable from rage, he plunged headlong into the open grave.

Everyone froze, then everyone moved. Some pressed forward to offer assistance, some pressed back to summon it. Ruby Huby leapt into the grave to succour her husband and landed with both knees in his kidneys. Eden Thackeray, no longer needing Miss Keech for aegis, released her and was then constrained to grab her again as she too started the easy descent into the pit. The vicar stopped smiling comfortingly and Rod Lomas looked across the grave, caught Lexie Huby’s eye, and laughed aloud.

Gradually order was restored and the unquiet grave emptied of all but its proper inmate. It was only now that most of those present realized that at some point in the confusion the catalystic stranger had vanished. Once it was ascertained that the only permanent damage was to John Huby’s blue serge, Miss Keech, still leaning heavily on the arm of Eden Thackeray, signalled that the obsequies were back on course by announcing that a cold collation awaited those who cared to return with her to Troy House.

Walking away from the graveside, Rod Lomas found himself alongside Lexie Huby. Stooping to her ear, he murmured, ‘Nothing in Aunt Gwen’s life, or her fortune for that matter, became her like the leaving of it, wouldn’t you say?’

She looked at him in alarmed bewilderment. He smiled. She frowned and hurried on to join her sister who glanced back, caught the young man’s eye, and blushed beneath her blusher at his merry respondent wink.