Loe raamatut: «Punished»

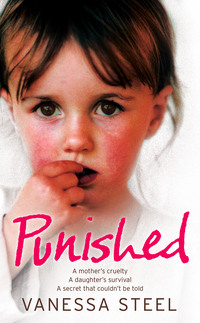

Punished

A mother’s cruelty

A daughter’s survival

A secret that couldn’t be told

Vanessa Steel

with Gill Paul

This is a work of non-fiction. In order to protect privacy,

some names and places have been changed.

Contents

Title Page Prologue Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Chapter Ten Chapter Eleven Chapter Twelve Chapter Thirteen Chapter Fourteen Chapter Fifteen Chapter Sixteen Chapter Seventeen Chapter Eighteen Chapter Nineteen Chapter Twenty Chapter Twenty One Chapter Twenty Two Chapter Twenty Three Chapter Twenty Four Chapter Twenty Five Chapter Twenty Six Chapter Twenty Seven Chapter Twenty Eight Chapter Twenty Nine Chapter Thirty Chapter Thirty One Chapter Thirty Two Chapter Thirty Three Chapter Thirty Four Chapter Thirty Five Chapter Thirty Six Chapter Thirty Seven Chapter Thirty Eight Chapter Thirty Nine Epilogue Acknowledgements Copyright About the Publisher

Prologue

I turned my key in the lock of Mum’s door and pushed, but it wouldn’t open. Something was stuck behind it, blocking it. I pushed harder but couldn’t shift the obstruction.

What’s she done now? I wondered. Is she deliberately trying to keep me out?

Then I looked through the letterbox and saw a beige- stockinged leg – her leg.

‘Mum!’ I yelled. ‘Mum, are you all right?’

Stupid question. Of course she wasn’t all right. I shouted at the top of my voice – ‘Help me!’ – and the next-door neighbour hurried out to see what was going on.

Stuttering with shock, I called for an ambulance and told the operator we’d probably need the fire brigade as well to break the door down. While we waited for them I sat on the step calling to Mum through the crack of the door but getting no response. Was that her breathing I could hear? I wasn’t sure. My heart was racing like crazy and so many thoughts flooded my head I felt dizzy.

No, she can’t die. Please don’t let her die!

I couldn’t help feeling guilty that I hadn’t been there when she needed me, even though I had been dropping in every day to do her washing and cleaning.

‘Hold on in there, Mum,’ I whispered through the door. ‘You can make it, I know you can.’

Tears filled my eyes as I heard a distinct, low-pitched moan. She was alive.

* * *

One of the ambulance men managed to get his arm through the crack and shift her so that they could get in without breaking the door down. They gave her oxygen and she regained a groggy kind of consciousness. I stood, useless, a huge lump in my throat and sadness engulfing me.

It was at that moment I realized that it was finally time to let loose all the dark childhood memories I had suppressed for decades. The woman lying crumpled on the floor and fighting for every breath had made my childhood a living hell. Now I knew I was in no way ready for her death, because while she was still alive I might be able to force her to answer the questions that had plagued me throughout my adult life.

What had I done to make her hate me so much that she did so many cruel things to me? Did she remember all the times she almost killed me? Why did she allow me to be a victim of terrible abuse? Why didn’t Dad or any other family member protect me from her? Why did I still feel a responsibility towards her and long for her to show me some affection, despite all that she had put me through?

As my mother was lifted into the ambulance, I knew that I didn’t have much time left to find out.

What crime had I committed? Why had she punished me, endlessly and thoroughly and with spite and cruelty, from the day I was born?

Chapter 1

Muriel Pittam was never really cut out to be a housewife and mother.

She was the second of Charles and Elsie Pittam’s four daughters, and judging from the photographs in the family albums, she was much prettier than her sisters. From the way she looks at the camera, you can tell that she knows she is cute and is challenging you to acknowledge it. The Pittams were not rich – Grandpa Pittam was a watch and clock repairer – but it’s obvious from the pictures of little Muriel in her pretty dresses and ballet tutus that she didn’t want for anything.

By the time she was in her twenties, Muriel Pittam was an absolute stunner, and she knew it. The photographs in the family album show her as a glamorous young blonde. In one picture she is leaning against a gate in a two-piece suit with a tightly belted waist and high-heeled shoes that must have taken her well over the six-foot mark. In another, she’s wearing a smart floral dress with a fitted bodice and flared skirt. There’s even one of her posed on a rock like a mermaid, wearing a bikini. Bikinis were only invented in 1947, the year after the A-bomb was tested on Bikini Atoll in the Pacific. Muriel must be wearing one of the first on the market.

All through my childhood, Mum often harked back to the glory days of her youth, when she worked as a seamstress and part-time model.

‘I used to make ball gowns, you know. Suits, day dresses, coats, wedding dresses, all of them hand sewn,’ she would say. ‘I worked for Isabel’s in Birmingham, where the fashionable ladies shopped. The wife of the head of Woolworths got her clothes there. And Arthur Askey’s wife. And I modelled. I had a perfect figure,’ she boasted. ‘Five foot eleven with a twenty-three-inch waist. My skin was flawless and photographers used to say I had the best profile they’d ever seen. There were photos of me modelling hats in the Daily Mirror.’

Young and gorgeous, Muriel Pittam had no problem attracting men. Over the years she often boasted to me about all the suitors she’d had and the marriage proposals she’d received and I’m sure it was all true. I saw at firsthand how she flirted with every man she came in contact with, from the plumber to her brothers-in-law. She obviously had the knack of twisting men round her little finger, with a shimmy of her slender hips and a coy smile. So when the youthful and less experienced Derrick Casey got within her sights – well, he didn’t stand a chance.

My father was engaged to a girl named Margery Wyatt when his elder sister Audrey brought home Muriel, her friend from the tennis club, for tea one day. The Caseys owned a very successful electro-plating business in Birmingham and Derrick already earned a good salary from it, so to Muriel’s eyes he must have seemed a good catch. The Caseys’ imposing house stood in several acres of grounds and they had a gardener and housekeeper to help run it. Thomas Casey was well connected as a prominent member of the local Conservative party and a leading figure in the Anglican Church. By contrast, the Pittams lived in a semi-detached house in a working-class area and had very little social life outside its four walls. It was obvious that Derrick was Muriel’s way out of a life as a seamstress and into a respectable and comfortable upper-middle-class life, so using her intelligence, her wiles and her physical charms, she set out to win his heart.

A lot of other men Dad’s age were called up to fight in the Second World War, but Derrick hadn’t been because he had a shattered kneecap after a cricket ball injury which left him with a permanent limp and unable to straighten his left leg. He still loved to play sports – golf, cricket, snooker – and he was also a great reader, particularly fond of Shakespeare and poetry. He looks unbearably young in photos of that time – plump-cheeked, dark-eyed, hair not yet receding but already wearing his customary shirt and tie in every shot. He’s the kind of man any young girl would have been proud to take home to their parents: upstanding and respectable, with a nice face without being conventionally handsome. Muriel’s fashion-model looks must have completely turned his head. In a matter of weeks, he broke off his engagement to Margery and asked Muriel to marry him instead, and she accepted straight away.

I remember once gazing at Mum’s engagement ring, a square-cut sapphire set in white gold and surrounded by little diamonds. I asked if I could try it on and she snapped, ‘No, you cannot. I had to work hard enough to get this ring and no one else is having it now.’

Who knows what kind of person Muriel pretended to be to enchant young Derrick Casey? The modelling shots she kept so carefully in the back of our albums show her statuesque and proud, her long neck and sculpted face a perfect foil for little pillbox hats with feathers on top, cartwheel straw hats or classic black toques. She’s slim as a gazelle but despite her beauty and elegance, she looks hard. You wouldn’t mess around with her.

No doubt she was sweetness itself in the run-up to her wedding and I suspect it was now that Muriel affected her act as a well-brought-up, church-going Christian girl. The Pittams weren’t religious at all, but the Caseys were staunch believers. It was important for Muriel to seem like the right sort of girl if she were going to be accepted as a member of the family and win Derrick’s affections. He was very devout, and often helped out at church fêtes and charitable events. No doubt Muriel seemed just as pious, although later, once she was safely married, she would dispense with formal religion and turn her own idea of God into a particularly dreadful weapon in her well-equipped arsenal.

Muriel and Derrick got married in 1941. The wedding photos are posed studio shots showing Mum with her hair swept up into a high style while she wears a dress of shimmering floor-length satin. She doesn’t smile in any of them but I can read a glint of triumph in her expression. She hadn’t just married into money; the Caseys were also very well connected socially. Now she could give up work and take her place in society as Mrs Derrick Casey, enjoying the dances and functions that they were invited to as a couple. The photos show her enjoying the fruits of her marriage: she’s never in the same outfit twice and the albums are full of pictures of my parents partying and socializing, relaxing on the beach, or standing in front of Dad’s brand new Ford motor car. Muriel, with her modelling background, is always camera-conscious, adopting a pose of some kind, with hair flicked back and lips pouting. They look like everyone’s idea of the glamour couple – young, attractive, well-off and in love.

* * *

In 1949, Muriel’s success seemed complete. She was blessed with the arrival of a baby, my brother Nigel. In the family photographs, he is an angelic-looking little thing, with white-blond hair and a shy smile. Mum holds him on her knee, looking at him and smiling, her attitude relaxed.

It’s a different story in the pictures that follow. In those, she holds a plump, ruddy-skinned, scowling baby. She never looks at it and there’s an obvious look of disgust on her face. She resembles one of those people who secretly loathe babies and who try to hide their dismay after someone has plonked one down on their lap. She is angry, tightlipped and bored. The baby she is holding is me.

I arrived in 1950, the year after my brother, and it seems that right from the start, my mother was displeased with me. In my baby pictures, even the earliest ones, I appear nervous and uncomfortable. I’m not smiling in any of the photos, except one where I’m being cuddled by Nan Casey, Dad’s mother. I look wary and uncomfortable and often on the point of tears. What had happened to make me like that?

‘You were such a cry-baby,’ I remember Mum saying. ‘Nothing I did was ever good enough for you.’

* * *

Any young mother who has had two babies in quick succession might feel stressed and possibly resentful. In Mum’s case, she claimed she had given up her dreams of success as a top model in exchange for two wriggling, crying babies. Her previously bright and buzzing social life was abruptly stopped – no more carefree evenings dancing and drinking with friends when there were two young children needing babysitters. Her whole life was now dominated by her routine at home with us. It must suddenly have seemed as though she’d picked a very short straw.

But thousands of young mothers had the same experience as they adapted to their new lives caring for children and a home. They didn’t become what my mother became, and their children didn’t suffer what I was to endure at the hands of the woman who was supposed to love me best in the world. Something in my mother was so bitter and resentful that she became evil. It’s a strong word, but I can’t think of any other way to describe what she did.

The danger signs were there from the very earliest days, when Nigel and I were still very young.

My first serious injury occurred when I was eighteen months old. Mum had left me on a bed and I rolled off on to the floor, breaking my leg. That was the story, anyhow. But although I have no memory of what happened, I do remember our house. The bedrooms were thickly carpeted and the beds not high off the floor. I was a plump, well- padded little thing. Would a roll from a low bed on to a soft carpet have been enough to break my leg? There were no witnesses, so I’ll never know.

There was a witness to another incident, though. Aunt Audrey told me that she glanced into the bedroom one night when Nigel was just one year old to see Mum holding a pillow over his face as he thrashed and writhed around.

‘Muriel, what on earth are you doing?’ she cried, rushing in to pull the pillow away.

Mum gave her a sharp look. ‘Sometimes it’s the only way to get him to stop crying,’ she said. ‘You know how I can’t stand listening to them cry.’

‘But he’s just a baby! You could kill him!’

Audrey said that Nigel’s breathing was very shallow and there was a blue tinge to his lips. Muriel shrugged and didn’t seem to take it seriously. Needless to say, Audrey made sure she never left any of her own children alone with Mum from that point on.

These things occurred before I was old enough to have any conscious memories. Once I do begin to remember, from around the time I was two years old, then the nightmare begins.

Chapter 2

I was a very timid child, shy around strangers and prone to creeping into my favourite little hidey-holes behind the settee or round the corner of Dad’s shed in the garden. I’d take Scruffy, a yellow-furred teddy bear, or Rosie, my rag doll, with me and could sit still for hours on end hugging them, out of sight of any adults.

I’m told I was very slow to talk. At two I’d hardly uttered a word and even at three I couldn’t manage more than a few incoherent phrases, so that Mum and Dad were beginning to worry that I was retarded in some way. Toilet training was also very traumatic for me. The slightest upset or fear could cause me to have an accident, which always enraged Mum. I was supposed to ask her permission when I wanted to go to the bathroom but she didn’t always grant it straight away, saying she was trying to train me to have more control. Several times when I asked to go, she made me squat down in the kitchen, bladder bursting and cheeks getting hotter, tiny fists clenched with the effort of trying to hold it in – and then there’d be the warm release of urine soaking my pants, that ammonia smell and a little puddle on the linoleum floor. Afterwards there was always the anger and the shouting, and my own sense of bewilderment at how I made her so cross.

The love of my life was Nigel, my big brother, much braver than me and always the ringleader in our games. He was a sweet-natured, affectionate child who had a bit of a temper when pushed. He never took it out on me, but injustice of any kind could make him see red. He wasn’t scared of things I was scared of, like dogs and noisy motorbikes and tradesmen who came to the door. I’d cower behind Mum’s skirt in the face of strangers, trying to avoid being noticed, while Nigel would stand his ground and ask questions like ‘Who are you? What’s your name?’ The roots of extreme shyness lie in a feeling that you are not quite good enough and you’re scared that other people will find out; I had that in spades as a toddler.

Nigel and I were solitary children, dependent on each other for company. I remember there were twins about our age living just up the road, but we were never allowed to play with them. We liked make-believe games, such as pretending that we were a king and queen going round the garden ruling over our subjects – in my case Scruffy and Rosie, and in Nigel’s his collection of wooden soldiers. Indoors, we would build little villages with houses and cars out of Bayko – a system of blocks and connecting rods somewhat like Meccano.

We rarely argued or fell out about anything. I remember one time I pushed him off his tricycle because he wasn’t sharing it with me, but that was exceptional. We agreed that we were going to get married when we were grown up, and then we would live together in a house of our own and be happy forever and ever.

Nigel and I rarely saw Dad during the week. I suppose he got home late from work when we were already in bed – and some nights, I know he didn’t get home at all. At weekends he’d be off playing cricket or golf at least part of the time. When he was there, though, I was Daddy’s little girl. He called me Lady Jane (Nigel was Little Boy Blue) and he carried me round the garden on his shoulders. We weren’t allowed out the front of the house – Mum didn’t like it – but while he was gardening out the back we’d follow him up and down as he mowed the lawn and persuade him to play chase or hide and seek with us.

He was a master of silly voices and we had to guess who each one was supposed to be. It might be Mickey Mouse or Little Weed from Bill and Ben, or any one of a number of cartoon characters. He was good at doing the animal noises in his rendition of ‘Old Macdonald’, and he was also very talented at whistling; the favourite tune I remember was ‘Blue Danube’.

We lived at number 39 Bentley Road, a large, stone-built, semi-detached house with bay windows and a big garden in a leafy, middle-class suburb of Birmingham. While my father looked after the outside, indoors was Mum’s domain, and it was kept spotless at all times. She would catch the dust as it fell, carefully lifting all her ornaments of pretty ladies in fancy hats from shelves and tables to make sure the surfaces were spick and span underneath. At the front of the house there was the immaculate dining room, whose bay windows overlooked the street. Nigel and I were only allowed in there on very rare occasions, but I remember a fold-up table in the bay with a chair by either side and a big picture of Jesus surrounded by a glowing halo on the wall. I would come to fear this room and what went on in there when Mum locked herself in it.

Upstairs there were three bedrooms and the bathroom. My bedroom was in some respects a little girl’s dream, with curtains and a bedspread made from a beautiful fabric printed with tiny pink and red rosebuds, some open and some closed, surrounded by sweeps of green stalks and leaves. The detail was extraordinary; I can remember the pattern of whorls and curlicues to this day. There were pink flannelette sheets and a bedside table with a pink lamp, and the glass in the bay window was made up of little twinkling squares. Woe betide me if I ever got a fingerprint on that glass; I learned from a very early age that it was a huge mistake to touch it as I peered out to see what was going on in the road below.

An outside observer looking at the room might have mistaken it for a seldom-used guest bedroom rather than a little girl’s room because there were no dolls, toys, pictures, books or teddies in sight. I was never allowed to bring Scruffy or Rosie up to bed with me. Bedrooms were for sleeping not playing, according to Mum, and upstairs was out of bounds during the day, except for permitted trips to the bathroom.

At the rear of the ground floor was a family room with large patio windows looking out on to the garden and a marble-effect tiled open fireplace. There was regency-striped wallpaper, a patterned carpet and a brown leather Chesterfield settee and matching chairs – all considered very chic in the early 1950s. You would never see any toys in evidence in that room – or anywhere else in the house for that matter. Nigel and I had very few toys and they had to be kept tidily out of sight in the family-room toy box if we wanted to avoid them being confiscated.

* * *

In my pre-school years I idolized my beautiful, glamorous mother. I thought that she was the most gorgeous woman in the world, with her perfect hair, red lips, rouged cheeks, long varnished nails and stylish outfits, always surrounded by a cloud of lily-of-the-valley scent. I liked watching her straightening the seams of her stockings, or reapplying the lipstick that she wore constantly, even in the house when there was no one else there except us kids.

‘Mummy pretty’ was one of my first phrases, but I was always aware that it wasn’t true of me.

‘You’re a very ugly child,’ Mum would tell me, pinching my cheeks. ‘No amount of makeup would camouflage that ugly mug. There’s not a lot we can do about it.’

I became obsessed with wanting to be pretty because I thought this would make Mummy love me and stop her being cross with me all the time. I’d gaze in the mirror, willing a different face to look back at me, but it never did.

One day when I was three I found Mum’s pot of rouge lying out in the bathroom. I managed to prise off the lid and put a couple of spots of it on my cheeks. I looked in the mirror and liked the effect, so I ran downstairs in great excitement to show her.

‘Look, Mummy, I’m pretty!’

‘What do you think you’re doing?’ she shouted, pulling me to her and rubbing hard at my cheeks with a dishtowel. ‘How dare you touch my makeup!’

I stood, horrified. I had honestly thought Mummy would laugh and would be pleased with me. How could it have gone so badly wrong?

‘You’re going to have to learn not to meddle with things that aren’t yours.’

I shrieked as she grabbed my hair and pulled me down the hall to the cupboard under the stairs, where the vacuum cleaner and other cleaning materials were kept. It had a sloping ceiling and shelves on one wall that served as a kind of pantry with lots of jars and tins and bottles. There was a bolt on the outside of the door and no light inside.

‘There’s a spider’s web in the corner.’ Mum pointed out. ‘I’m going to lock you in here for a while to keep you out of mischief, but you’d better stay very, very quiet and very still or the spiders are going to get you.’

I was shoved inside and the door slammed and bolted. I could just make out a thin outline of the light round the door through the musty darkness. I gulped back my sobs, trembling with fear, and felt that familiar trickle between my legs as I wet myself. I didn’t dare sit down or reach out my hands to touch the wall or make any movement or noise. I could barely breathe. I genuinely thought the spiders were going to eat me. How could I know otherwise?

Soon I became hysterical, banging and kicking the door as hard as I could and screaming at the top of my voice. I heard Mum’s footsteps come clicking down the hall. She opened the door and I reached up my arms to be lifted, hoping for a comforting hug, but instead she hit me across the head with a sharp admonition to ‘shut up!’ Then she slammed and bolted the door again. I was shocked into silence. My legs trembled and an occasional sob escaped me but otherwise I stood quietly, alert for the feel of a spider’s creepy feet on my skin or a nibble from their fangs. More than the physical fear, though, I felt the terror of being abandoned by the person who was supposed to take care of me. I was only three and I was bereft of adult protection.

At last, after an interminable period, Mum opened the door and yanked me out again. ‘How many spiders did you count? Did they bite your toes?’ There was a malicious glint of pleasure in her eyes as I shivered with fear, longing in vain for a kind word.

This is the first real punishment I remember Mum inflicting on me. Far from being a one-off, confinement in the spider cupboard became an almost daily occurrence. Young children don’t have much of a sense of time but I know that sometimes it was broad daylight when I was thrown in there and dark when I came out. I frequently missed meals and had to push my fists into my stomach to combat the rumblings of hunger. If he was feeling brave, Nigel would come and whisper to me through the crack of the door: ‘It’s all right, Nessa, I’m here – don’t be scared.’ But as soon as Mum heard him he would be dragged away.

It was hard to predict the crimes for which I would be locked in the cupboard. Picking flowers, scribbling in my Noddy book, spilling a little talcum powder on the bathroom rug, squealing, asking for a drink, not finishing my supper – any of these could result in a period in captivity.

Nigel and I had the natural liveliness you’d expect of any toddlers and we could be naughty with the best of them. One day we shook the petals off the rose bushes and laid them out all over the garden path in wavy patterns. Mum went absolutely berserk when she saw them because, she said, we had ‘stolen’ Dad’s flowers.

Another time a painter had left a ladder leaning against the wall at the back of the house and Nigel and I decided to climb it to see how high we could get. He went first and had almost reached the bedroom window when he fell to the ground below and his screams brought Mum rushing out. I remember that I was the one who was punished for that escapade, despite the fact that he was older and had been the ringleader.

‘I’m going to give you away to the ragamuffin man next time he comes,’ she’d taunt, a prospect I found very scary, although I didn’t have a clue what a ragamuffin man was.

‘No, Mummy, please,’ I’d beg tearfully, but she would maintain that next time he came she was definitely going to hand me over.

* * *

There were some mornings when Mum woke up in a foul mood with the world and couldn’t stand the sight of me so I’d be locked in the cupboard from breakfast onwards. My only respite was at weekends when Dad was around, or on the two mornings a week when Mrs Plant, our cleaner, came over.

Mrs Plant was a lovely, dark-haired lady with a lively imagination. She would lift me up to sit beside the sink while she washed dishes or peeled potatoes and made up lots of stories to tell me. She couldn’t understand why I started crying when she told me about Little Miss Muffet who sat on a tuffet. I was too young and too inarticulate to be able to put into words the chronic fear of spiders that had taken hold of me, so that even a mention of one in a nursery rhyme was distressing.

I wonder if she ever suspected what was going on in that household when she wasn’t around. Once, when she was cleaning the cupboard under the stairs, I said to her, ‘That’s my place for when I’m naughty.’

She looked aghast and turned to Mum, who had emerged from the kitchen.

‘What an imagination the child has!’ Mum smirked. ‘Have you ever heard the like?’

‘Mummy put me there,’ I protested.

She raised her eyebrows at Mrs Plant and winked. ‘Was that in one of your story-books, darling?’ she asked me.

Mrs Plant looked relieved and went back to work, obviously content with Mum’s explanation. I was to learn that this would always happen when I tried to tell other adults the truth about what went on in our house. Mum was the mistress of keeping up appearances and from the outside, we looked like a typical, middle-class family: two happily married, prosperous parents and their well-turned-out son and daughter. Neighbours in Bentley Road undoubtedly saw us as completely normal, if a little insular.

What they didn’t realize was that our father increasingly spent as much time as he could out of the house, leaving us at the mercy of a mother whose resentment of her two young children was growing, and with it, her desire to punish them.

Tasuta katkend on lõppenud.